- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

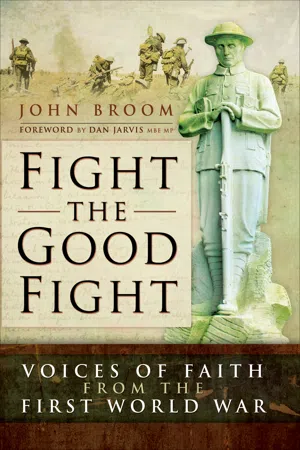

Fight the Good Fight: Voices of Faith from the First World War

About this book

"The inspiring stories of a number of very different characters who used their Christian faith to cope with their experiences of the First World War." —Jacqueline Wadsworth, author of

Letters from the Trenches

While a toxic mixture of nationalism and militarism tore Europe and the wider world apart from 1914 to 1919, there was one factor that united millions of people across all nations: that of a Christian faith. People interpreted this faith in many different ways. Soldiers marched off to war with ringing endorsements from bishops that they were fighting a Godly crusade, others preached in churches and tribunal hearings that war was fundamentally against the teachings of Christ. Whether Church of England or Nonconformist, Catholic or Presbyterian, German Lutheran or the American Church of Christ in Christian Union, men and women across the globe conceptualized their war through the prism of their belief in a Christian God.

This book brings together twenty-three individual and family case studies, some of well-known personalities, others whose stories have been neglected through the decades. Although divided by nation, social class, political outlook, and denomination, they were united in their desire to 'Fight the Good Fight.'

"John Broom looks at such beliefs during the first world war—the Tommies were always fighting for God, the king and their country . . . a fascinating study." — Books Monthly

"A detailed study of a usually hidden aspect of wartime social history, the topic of Christian faith. Fight the Good Fight has been meticulously researched and includes a wealth of previously unpublished material." — Come Step Back In Time

While a toxic mixture of nationalism and militarism tore Europe and the wider world apart from 1914 to 1919, there was one factor that united millions of people across all nations: that of a Christian faith. People interpreted this faith in many different ways. Soldiers marched off to war with ringing endorsements from bishops that they were fighting a Godly crusade, others preached in churches and tribunal hearings that war was fundamentally against the teachings of Christ. Whether Church of England or Nonconformist, Catholic or Presbyterian, German Lutheran or the American Church of Christ in Christian Union, men and women across the globe conceptualized their war through the prism of their belief in a Christian God.

This book brings together twenty-three individual and family case studies, some of well-known personalities, others whose stories have been neglected through the decades. Although divided by nation, social class, political outlook, and denomination, they were united in their desire to 'Fight the Good Fight.'

"John Broom looks at such beliefs during the first world war—the Tommies were always fighting for God, the king and their country . . . a fascinating study." — Books Monthly

"A detailed study of a usually hidden aspect of wartime social history, the topic of Christian faith. Fight the Good Fight has been meticulously researched and includes a wealth of previously unpublished material." — Come Step Back In Time

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Christian Britain in 1914

‘Onward Christian Soldiers, Marching as to War’

‘Without appreciating its religious and spiritual aspects, we cannot understand the First World War.’1 So wrote Philip Jenkins, Professor of History at Baylor University, Texas. That war was of immense scale in the way it affected life in these islands. In Britain alone there were 705,000 fatal casualties, with a further 300,000 fatalities from men as far afield as India, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and South Africa fighting as Empire forces.2 From 1914 to 1918, nearly 5 million British men volunteered or were conscripted to join the regular army of 800,000 – one in every five males in the country.3 Of these, nearly 80 per cent were English, 9.6 per cent Irish, 8.6 per cent Scottish and 2.4 per cent Welsh.4 Due to the relatively small size of the British Regular Army, Lord Kitchener created a ‘New Army’ of thirty divisions of volunteers in 1914–15. This new army had strong local connections, being identified with certain counties or cities, most notably in the ‘Pals’ battalions. After the introduction of conscription across Great Britain (but not Ireland) in 1916 and the need to fill the massive gaps in the regionally based battalions after the horrific losses during the Somme campaign of that year, that sense of local identity became diluted. Within this changing nature of the British Army, Christianity had a strong hold at all levels, from Sir Douglas Haig through to the modest private.

In pre-war England, as opposed to the whole of Britain, 60 per cent of the population was Anglican, 15 per cent Nonconformist and 5 per cent Catholic, with the other 20 per cent agnostics or belonging to other denominations.5 However, for many this was a nominal adherence. Figures have been produced that show there were 5,682,000 official adherents of Protestant denominations across the whole of Britain, out of a total population of 42 million.6

The church had grown marginal in working-class areas, especially in the north of England and particularly amongst men. The Church of England in particular had many nominal adherents whose church attendance ranged from patchy to almost non-existent. To some extent, Nonconformism had filled the religious gap in urban areas and Wales. Due to the somewhat fundamentalist nature of Nonconformism, members tended towards a more active faith than many Anglicans.

In the early 1900s there was still institutional discrimination against Catholics in many sections of society. Despite the presence of a handful of large landowners in the House of Lords, there were relatively few members of the Catholic middle class. Where there were larger numbers of adherents of Catholicism was in the industrial cities of the north. Joseph Garvey, whom we shall meet in this section, is an example of this milieu. There was little reason to be a nominal Catholic or Nonconformist, so, whilst lacking the numbers that the Church of England could claim, there was perhaps a higher level of belief and devotion amongst their adherents. Catholics and Nonconformists were very different in their approach to ritual and symbolism but to be a member of either was to stand outside of the mainstream Church of England.

This advance of Nonconformism, the growth of Catholicism particularly as a result of Irish immigration, and the resultant increased efforts of the Church of England to maintain its supremacy as the national denomination had led to a situation in which ‘the generations alive in 1914, particularly among the working classes, had been exposed to greater religious influence than at any previous time.’7 However, this did not mean that Christianity was all-triumphant. Archaeological and scientific criticisms of the traditional interpretation of the Bible had challenged the infallibility of scriptural knowledge, whilst some objected that Christian evangelisation smacked too much of the middle classes preaching down to the working classes, and many in the Anglican church were wary of people being nominal, rather than active, Christians.

In general, British Christians gave full support to Britain’s war effort. For Nonconformists, the ‘rape of Belgium’ could be equated with the Nonconformists’ struggle against the dominance of the Church of England. Up until 1916, army recruitment followed the voluntary system, which appealed to their sense of free, individual moral choice. The Church of England had given official credence to the just war theory in its Articles of Religion of 1571, one of which stated, ‘It is lawful for Christian men, at the commandment of the Magistrate, to wear weapons and serve in the wars.’8 One of the obligations of being the established church of the state was allowing Christians to fight for that state. The Church of England also played an important role in wartime propaganda. It helped to transform a war begun for strategic political and economic interests into something approaching a holy war. Many clergy preached patriotic sermons and senior churchmen emphasised the moral and spiritual superiority of Britain’s war aims. Arthur Winnington-Ingram, the Bishop of London, put this case in December 1915: ‘No one believes more absolutely than I do in the righteousness of this present war; as I have said a thousand times, I look upon it as a war for purity, for freedom, for international honour, and for the principles of Christianity. I look on everyone who fights for this cause as a hero, and everyone who dies in it as a martyr.’9

The tradition of British Protestantism and the right of the individual to read and interpret the teachings of the Bible in a personal manner, stretching back to the time of the Reformation and beyond to John Wyclif, still held strong. Thus a huge spectrum of interpretations of its perspective on warfare led people to advocate the most ardent nationalism through to the most passionate pacifism. Some recalled that the most prominent influencer of the Reformation, Martin Luther, was himself German and therefore saw beyond national boundaries, whilst others saw Britain in the tradition of Cromwell, Wesley and Bunyan and accused Germany of being the source of a more liberal and critical attitude towards the Bible.

Lloyd George, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer of the Liberal government, addressed an audience of 3,000 Nonconformists at the City Temple on 10 November 1914, calling for them to show sympathy with the cause of justice and the small nationalities. The chair of the meeting declared, ‘If we had not been Christians, we should not have been in this War. It is Christ …who has taught us to care for small nations and to protect the rights of the weak … The devil would have counselled neutrality, but Christ has put His sword into our hands.’10 He compared Britain to the Good Samaritan coming to the aid of the stricken. The painting The Great Sacrifice by James Clark, published in The Graphic magazine in 1914, counterposed Christ’s crucifixion with that of a slain British soldier. Some saw the war as a chance for Britain to turn its back on materialism, social division and selfishness and embrace that idea of sacrifice leading to a state of grace.

In Ireland, 92,000 men had enlisted by 1916, about half of whom were Catholics.11 John Redmond, the nationalist MP, calculated that a display of loyalty from Ireland would advance the cause of Home Rule. In a similar tone, the Irish Catholic All Hallows Journal argued that support for the war would advance Irish independence.

Historians have argued for the notion of a ‘diffusive Christianity’, or the underlying strain of popular religion that permeated much of British society – a cultural ideal of Christian behaviour that was widely shared.12 This was a Christianity that went beyond mere church attendance; ‘Even if Christian belief was declining, which is a proposition difficult to prove, and one which is more questionable than secularisation theorists suggest, this does not mean that the habits of thought and the unspoken assumption had disappeared.’13 Regular church-going was common among the upper classes and therefore Christianity played a large role in the public life of the country.

In addition, Britain had a history of Sunday school education stretching back to the 1780s and by the mid-nineteenth century religious education, either in day or Sunday school, had extended to most rural and urban areas. In 1888 about three out of four children attended Sunday schools. In 1906, Wesleyan Sunday schools taught more than a million children.14 The Primitive Methodist movement could point to ‘a continued enlargement of Sunday school work’, and significantly, ‘the retention for a longer period than formerly of the Scholars in the Schools, the increasing number of select and Adult Bible Classes’.15 However, for many, this was where their experience of religion ended, leading to a disconnection between the juvenile and adult male and the daily life of the churches.

As well as bringing forth the notion of a Christ-like sacrifice, it was also seen that the war provided a biblical backdrop to some of its events. Damascus had seen the empires of Babylon and Nineveh rise and fall, and was now witnessing the impact of ‘the Kaiser’s ill-starred and horrible war’.16 The Times reported how British soldiers had ‘camped near to the rivers where the exiles of Israel hanged their harps; they have pursued the fleeing enemy along the road which led from Egypt to Babylon; they have known the cities to which St Paul wrote.’17 One soldier wrote to his parish magazine in Cheshire to say the war had taken him to Hebron and Bethlehem, and he had received a special commemorative card from his padre for receiving Easter communion in Jerusalem.18 Three of the case studies in this book – Philip Bryant, Russell Barry and J.V. Salisbury – refer to their war in those biblical lands.

That people could relate their war to stories from the Bible shows its importance in the British culture. ‘The English Bible is the first of treasures,’ King George V had stated in 1911.19 The War Office already had well-established protocols for handing out religious literature to regular soldiers, but the vast expansion of the British Armed Forces between 1914 and 1918 meant that Christian trusts and charities enhanced this provision. The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), the Religious Tract Society, the British and Foreign Bible Society, the Scripture Gift Mission (SGM), the Pocket Testament League and the Trinitarian Bible Society all endeavoured to provide whole Bibles, New Testaments, individual Gospels, Psalms and the Book of Proverbs, as well as prayer cards and hymn books. Whilst estimates are very difficult to come by, Alan Wilkinson suggested a number of 40 million pieces were distributed from 1914 to 1916.20

In the front of the SGM Bible was found a message from Lord Roberts, a hero of the Afghan and Boer Wars, to the troops, dated 25 August 1914:

I ask you to put your trust in God. He will watch over you and strengthen you. You will find in this little Book guidance when you are in health, comfort when you are in sickness, and strength when you are in adversity.

These particular Bibles contained a section at the back where the serviceman could sign a personal commitment to Christ. It is claimed that many grieving families were comforted by the sight of that page signed by their loved one when the deceased’s possessions were returned. Richard Schweitzer has identified three main areas of the use of the Bible for the British serviceman in the First World War: drawing general strength and comfort from its possession; providing solace in wounding and death; and the importance of specific readings or quotations that were marked or commented on in letters or diaries. Schweitzer concluded that the Psalms were the most popular texts in the final context, followed by the Gospels of St John and St Matthew. In general, the Psalms excepted, the New Testament proved more popular than the old.21

However, in some ways the Bible had been at relatively low ebb by 1914. James Bryce, former ambassador to the United States, commented in early 1914 that, ‘It is with great regret that one sees in these days that the knowledge of the Bible seems to be declining in all classes of the community.’22 Just a year later, the mayor of Bath was able to comment that one of many results of the war was a rediscovery of the Bible, and it was ‘being read in England more readily that it had been for many a long day.’23

A Times article on 19 August 1916 considered the changed importance of the Bible in wartime.24 The anonymous correspondent claimed that the words of the Bible had shown a personal understanding of the situation of British people in wartime in a number of ways. As the war demanded new standards of service and sacrifice, the correspondent thought that the Holy Scriptures had presupposed this demand, and that a link had been created between the prophets and apostles on the one hand, and the members of the modern British nation on the other. There was a ‘feeling of intimacy with something living and personal in the words of the Bible’. The article identified four separate parts of the Bible as being of particular significance during the war. Firstly, the Psalms had developed a particular reson...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: Christian Britain in 1914

- Part II: Three Chaplains and an Army Scripture Reader

- Part III: Women in War

- Part IV: Christians from Other Nations

- Part V: Conscientious Objection in the First World War

- Part VI: Families in War

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fight the Good Fight: Voices of Faith from the First World War by John Broom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.