- 241 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

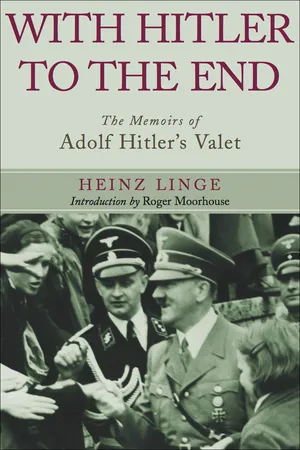

About this book

"Creepy yet fascinating . . . Of interest to anyone seeking more insight into the everyday life of one of history's monsters" (

Library Journal).

Heinz Linge worked with Adolf Hitler for a ten-year period from 1935 until the führer's death in the Berlin bunker in May 1945. He was one of the last to leave the bunker and was responsible for guarding the door while Hitler killed himself. During his years of service, Linge was responsible for all aspects of Hitler's household and was constantly by his side. He claims that only Eva Braun stood closer to Hitler during these years.

Through a host of anecdotes and observations, Linge recounts the daily routine in Hitler's household: his eating habits, his foibles, his preferences, his sense of humor, and his private life with Braun. In fact, Linge believed Hitler's closest companion was his dog. After the war, Linge said in an interview, "It was easier for him to sign a death warrant for an officer on the front than to swallow bad news about the health of his dog."

In a number of instances—such as with the Stauffenberg bomb plot of July 1944—Linge gives an excellent eyewitness account of events. He also gives thumbnail profiles of the prominent members of Hitler's "court": Hess, Speer, Bormann, and Ribbentrop among them.

"Now [Linge's] incredible story has been translated into English for the first time and casts new light on what it was like to be constantly alongside the Nazi despot." — Daily Mail

Heinz Linge worked with Adolf Hitler for a ten-year period from 1935 until the führer's death in the Berlin bunker in May 1945. He was one of the last to leave the bunker and was responsible for guarding the door while Hitler killed himself. During his years of service, Linge was responsible for all aspects of Hitler's household and was constantly by his side. He claims that only Eva Braun stood closer to Hitler during these years.

Through a host of anecdotes and observations, Linge recounts the daily routine in Hitler's household: his eating habits, his foibles, his preferences, his sense of humor, and his private life with Braun. In fact, Linge believed Hitler's closest companion was his dog. After the war, Linge said in an interview, "It was easier for him to sign a death warrant for an officer on the front than to swallow bad news about the health of his dog."

In a number of instances—such as with the Stauffenberg bomb plot of July 1944—Linge gives an excellent eyewitness account of events. He also gives thumbnail profiles of the prominent members of Hitler's "court": Hess, Speer, Bormann, and Ribbentrop among them.

"Now [Linge's] incredible story has been translated into English for the first time and casts new light on what it was like to be constantly alongside the Nazi despot." — Daily Mail

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access With Hitler to the End by Heinz Linge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

I Join Hitler’s Staff: Elser, the Admired Assassin

JUST ONCE TO BE in the presence of Adolf Hitler, even as a duty, was then the wish of millions. Just once, or should I say, ‘so long as everything was going well’. Envy accompanied me when in 1935, to my surprise, the choice fell on me to join Hitler’s household. Surprised, for I saw nothing special in myself which would justify such a distinction. I had got my certificate of secondary education, had worked in the construction industry and taken mining training in the hope later of becoming a mining engineer. I joined the Waffen-SS in my home town Bremen in 1933 and after a one-year spell with the unit at Berlin-Lichterfelde, in July or August 1934 with about two dozen comrades I was detached from my unit to the ‘Berg’ as No. 1 Guard: to Obersalzberg, the country seat of Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler. Hitler appeared on the Berghof terrain, shook everybody by the hand and asked questions about our private lives. He asked me where I came from and my age. This meeting with Hitler, an idol for us young soldiers, made a deep impression on me.

At the end of 1934 it was arranged that two men from the platoon would be selected for the Reich Chancellery. The selection procedure lasted several days, and finally Otto Meyer and I were chosen from a list of fifty. We reported to SA-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Brückner, Hitler’s chief adjutant, who revealed that we were to be attached to the Führer’s personal staff. After a short course at the hotel training school, Pasing near Munich, in January 1935 we served in some of the Reich Chancellery departments under Brückner’s tutelage. (In 1936 he published a widely read article about the Führer in his private life.)

Finally we were assigned to our duties in the ‘Personal Service of the Führer’. Karl Krause, a manservant from the Reichsmarine who had been with Hitler since 1934 awaited us with our instructions. We three were to share the duties amongst ourselves. Hitler wanted to have one man with him constantly. The second man was to accompany him on his travels. This man had the additional task of ensuring that Hitler’s clothing and private rooms were in good order, for which purpose he had a chambermaid at his disposal. The third man was to handle the business arrangements in Hitler’s household.

On major occasions, on extended journeys and at Party rallies, the three of us would accompany Hitler. Our apparel had to coincide with his. Everything always had to appear exactly the same. On Party occasions we wore SS uniforms. If Hitler wore a civilian suit, not unusual prewar, then we had to wear one too. Whoever believes that Hitler did not want to appear too obvious for fear of assassination attempts is mistaken. In September 1939 during the Polish campaign he advanced beyond our frontline, and I never saw any sign of anxiety in him. I am convinced, however, that when he emphasised repeatedly for propaganda purposes that he had been ‘selected by Providence’ for a great, unique, historical mission, he did actually believe it. Rudolf Hess once told me that just before the seizure of power, Hitler, Hess, Heinrich Hoffmann and Julius Schaub were all nearly killed in Hitler’s Mercedes due to an error by a lorry driver. Hitler was injured in the face and shoulder but with great composure calmed his co-passengers, still paralysed with shock, with the observation that Providence would not allow him to be killed since he still had a great mission to fulfil. He did not fear attempts on his life, and it was obvious to him that he had to move about freely. When concerns were uttered for his safety he said: ‘No German worker is going to do anything to me.’ That such an attempt might come from some other sector he seemed to discount, or until 1944 at least. He rejected all obvious safety measures as exaggerated. When during a public meeting at the Berlin Sportspalast the police advised him to enter the hall by a special entrance, because otherwise they could not guarantee his safety, he rejected this brusquely with: ‘I am not going in by some back door!’ When he undertook private journeys, he forbade his Kripo escort to make a passage for him through the crowd and to shield him. He believed and often stated that ‘Providence’ protected him and that the mere presence of the SS bodyguard was sufficient to dissuade all would-be assassins. What engaged his thoughts more was the possibility of an attempt from abroad to remove him by force. Political fanatics were also to be found in the Reich, he said once, so that he had to live with the possibility of surprises in this respect too. All the same, he was not especially concerned about who was around him and his ‘court’. He knew the people at the Berghof by sight but only a few of them by name and employment. It was the same at FHQs. After moving in he would do the rounds, have the various commanders presented to him and content himself with that.

After my release from Russia I was surprised to see the assertion still hawked today that it had been almost impossible to get close enough to Hitler to murder him. This is incorrect. Whoever had cunning, skill and determination could have assassinated Hitler on any one of very many occasions. Often, and not only before the war, people approached him without anybody intervening. Photographers and cameraman dragged into his presence cases of equipment, cables, tripods and film materials, took photographs of him with telescopic lenses and generally moved about freely and unhindered. After the July 1944 bomb plot when preparing to be driven to the military hospital at Rastenburg, he was suddenly surrounded by a large crowd of soldiers and police. Any of them could have killed him had they been so inclined. Although still suffering from wounds to his head and legs from the bomb he was so unmoved by it all that I became anxious for his safety and only relaxed when we finally drove off. Sitting behind him, I could at least protect his back. Admittedly, anyone who wanted to remove Hitler ‘eye to eye’ would have had to sacrifice his own life. This kind of suicide mission found no takers and was probably the only reason that Hitler survived to die by his own hand in April 1945.

Only very few of the attempts on Hitler’s life are known publicly. Some he escaped very closely. After the marriage of Generalfeldmarschall von Blomberg, Hitler drove to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s former mansion and hunting range on the Schorfheide to be with Göring. Himmler drove ahead of us. Suddenly shots cracked out from the forest undergrowth. Himmler’s car stopped after being hit. Himmler, deeply shocked and pale, told Hitler that he had been shot at. Driving on after the incident, Hitler said: ‘That was certainly intended for me because Himmler does not usually drive ahead. It is also well known that I always sit at the side of the driver. The hits on Himmler’s car are in that area.’ The result was that Hitler’s cars were given armour plating.

Shortly before the war an adjutant accepted for Hitler a bouquet of roses from the crowd. After the adjutant reported the sudden onset of a mysterious illness the bouquet was examined and it was found that the thorns had been treated with poison. This ‘flower attempt’ had as its consequence a ruling that flowers and other objects had to be handled in future only when wearing gloves. Later the tossing of flowers into Hitler’s car was in general forbidden. One day, dog-lover Hitler was given a dog as a present. The animal had been infuriated in some way, but this was detected when it bit one of the escort. Hitler was always lucky (except for his injuries on 20 July 1944) but early on had gradually become more cautious. Foods from abroad could not be eaten in the household. Despite this prohibition, in 1944 I had not been able to resist the temptation to taste a gift of fruit. The result was a bout of poisoning diagnosed by Dr Morell, Hitler’s personal physician, which kept me in bed for weeks. Hitler was examined daily by his doctor while Reichsleiter Albert Bormann was ordered to test not only all food but also the water daily.

The first attempt on Hitler’s life to become widely known and arouse excitement worldwide occurred in Munich in 1939. In the so-called ‘Capital of the Movement’ on the eve of the commemoration of the march to the Feldherrnhalle of 9 November 1923, a reunion of the Alte Kämpfer was scheduled in the Bürgerbräukeller. Hitler was to take part as usual. The war was two months old and Hitler, who needed to be in Berlin on the morning of 9 November, arranged for the reunion to begin early and cancelled his usual meeting with old comrades. This decision saved his life.

The following communiqué was published in the German Press on 9 November 1939:

On Wednesday (8 November) the Führer made a brief visit to Munich for the commemoration celebrations of the Alte Kämpfer. The Führer himself delivered the address in the Bürgerbräukeller in place of Party member Hess. Since affairs of state required the attendance of the Führer in Berlin that night, he left the Bürgerbräukeller earlier than originally planned and boarded the waiting train at the main station. Shortly after the Führer’s departure an explosion occurred in the Bürgerbräukeller. Of those still present in the room seven were killed and sixty-three injured. The assassination attempt, which by its traces appears to have been a foreign plot, caused immediate great outrage in Munich. A reward of 500,000 RM has been offered for the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators, and a further 600,000 RM from private sources. The devastating explosion in the Bürgerbräukeller occurred at about 2120 hours, at a time when the Führer had already left the hall. Nearly all leaders of the Movement, Reichsleiters and Gauleiters, had accompanied him to the railway station, where he boarded the train for his return to Berlin on urgent state business immediately after concluding his address. One must consider it a miracle that the Führer escaped the attempt with his life. The attempt was a blow struck against the security of the Reich.8

A fortnight later it was announced that thirty-six-year-old Johann Georg Elser had been arrested shortly after the attempt while trying to cross the frontier into Switzerland. He was said to have been the man who placed the bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller about 145 hours before the explosion. I was with Hitler when Himmler delivered his report. Elser, born 4 January 1903 at Hermaringen/Württemberg as the illegitimate son of a heavy drinker of the locality, a wood merchant by the name of L. Elser, had confessed his intention to kill Hitler. According to Himmler’s statement, Elser was ‘no carbon copy of the Reichstag arsonist van der Lubbe’. Elser had declared that he alone knew of his preparations for the attempt and nobody had put him up to it. When Himmler said that in his statement Elser admitted to being obsessed by the idea of having his photograph in the newspapers, Hitler asked for a photograph to be produced.

The man had admitted wanting to be a ‘Herostratos of the present’,* Himmler went on. Hitler, who was studying the photograph, listened at first with a granite face, then said slowly: ‘Himmler, that does not seem right. Just look at the physiognomy, the eyes, the intelligent features. This is no seducer of men, no chatterer. He knows what he wants. Find out what political circles are behind him. He may be a loner, but he does not lack a political point of view.’ Himmler made a surprised face and assured Hitler that his people would soon find out ‘whose spiritual child’ the would-be assassin was.

Elser interested Hitler in an odd way. The man whose philosophy in the Ernst Röhm affair and elsewhere was to ‘kill, shovel out the shit’, reacted to Elser quite differently. When he saw Himmler’s mystified expression he said under his breath: ‘I am allowing him to live only so that he knows I am right and he is wrong.’ Himmler, disconcerted, went off to make his further enquiries. Soon afterwards Hitler received details about Elser’s career. As the eldest of five children he had left school in 1917 to train as a turner in an iron foundry at Königsbronn, but gave this up to train in carpentry, qualifying two years later. The best of his class in 1922, he considered himself an ‘artistic carpenter’ and experimented with ideas involving clocks, motors and locks. Next Elser obtained employment at Dornier’s Friedrichshafen aircraft works in the propeller section for three to four years, where he was a good worker. He went on to spend a year in a clock factory where he proved sociable, was a good zither and double-bass musician and had various affairs with women.

All this reinforced Hitler’s original impression, and he reproached Himmler: ‘Herostratus? Just look – member of the Woodworkers’ Union, member of the Red Front Fighters’ League and a churchgoer – and no political motive? How could he make anybody believe that?’ Hitler had completed his assessment of Elser and ordered Himmler to get Elser to build another bomb. Elser obliged. ‘This man’s abilities,’ Hitler said in recognition of them, ‘could be useful in wartime, blowing up bridges and suchlike. Give him a workshop in a prison or concentration camp where he can continue his bomb-making activities.’

As a ‘special detainee’ (Sonderhäftling) at Sachsenhausen concentration camp Elser was grouped together with Léon Blum, Kurt von Schussnigg, Pastor Niemöller and a number of other well-known personalities and worked for years on the task Hitler had given him. He invented, designed and built bombs to Hitler’s order. Hitler suspended the criminal proceedings against him, something that may have surprised the public. It is alleged occasionally that Hitler knew in advance of a bomb having been placed in the Bürgerbräukeller, and this was the reason why he had arrived and left earlier than planned. For my own part I knew Hitler’s reactions and was able to tell reliably from his composure if he were genuinely surprised or just pretending, and it was my opinion in November 1939 that he had no foreknowledge.

I guessed that within his trusted circle Hitler had no desire to speak of his frustration at the British response to the invasion of Poland. A number of the Party bosses, the Gauleiter Rudolf Hess, Goebbels (who accompanied Hitler to Berlin) and others might have spoken privately at the Bürgerbräukeller of his prophecy about Britain’s ‘friendly’ attitude to the Reich. This would certainly not have pleased him. According to Himmler, Elser had done no harm to Hitler, had expressly recanted, admitted his guilt and changed his outlook at Sachsenhausen. He told several people there that the Gestapo paid him 40,000 Swiss francs to plant the bomb and set the timer for the hour they wanted. I never dared broach this subject with Hitler. When the official police bulletin on 16 April 1945 reported the death of Elser the previous day in an Allied bombing raid, a somewhat noteworthy occurrence, I had other matters to concern me. Defeat was at hand.

Hitler’s composure on the day of the assassination attempt and the fact that Elser would have had to spend all day in the Bürgerbräukeller undiscovered near the column where he had put the bomb seem noteworthy in retrospect, bearing in mind how Himmler’s security organisation automatically made its screening preparations for meetings of this kind. In my opinion Hitler’s reaction after the attempt was not feigned: it seemed too original, too spontaneous. At that time I would not have believed it possible of him to risk the lives of the Alte Kämpfer without betraying himself in some way.

A lot about the Elser case was extraordinary. That Hitler allowed Elser to go on living because, as he informed Himmler, his inventive abilities could be useful in the war, seemed very questionable to me in 1939, for our experts were in no need of a clockmaker/carpenter to provide them with ideas. I had the impression that Hitler admired Elser’s quiet dedication and constancy. Elser was basically a man whom he would have liked to have seen active in the SS, SA or the Party. Elser, the ‘simple worker’ as Hitler once called him, had the courage at the end of 1939 to do something for his ‘political world-view’ when German generals opposed to Hitler had merely resigned. Hitler, who drew attention to himself in Mein Kampf and in public speeches as having once been a ‘simple worker’, was always more impressed by special achievements from this level than by corresponding efforts of the so-called ‘higher-ups’. He was convinced that the workforce belonged to him ‘heart and hand’. More than once he said that he would lay his head to sleep in the lap of any German worker without the least fear. He never accepted that the workers only followed him because he gave them work and bread after years of despair, as is often maintained nowadays.

The Elser case was something special for him without a doubt. Since the Nuremberg trials we have come to understand how the lives of people in Hitler’s Germany counted for very little. This can be confirmed by reading the death sentences from that time. Thus we have a mystery how Elser, whom Hitler ought to have wanted dead, stayed alive almost to the end when the men and women around Graf von Stauffenberg in 1944 were hanged like cattle. Workers who went through thick and thin to ‘follow the mismanaged nobility’ were also lost to Hitler in principle, while Thälmann the German communist leader and Elser were for him ‘men of character’ in whom he saw much to be admired. It seems to me that this aspect of his personality lacks research. I read often after the war that Hitler was so fearful of assassination attempts he always had the window blinds let down when he travelled by train. This was not the reason: his eyes were intolerant of sunlight. Even bright artificial light hurt them and accordingly his headwear always had a large brim, or peak worn low. Heinrich Hoffmann, his personal photographer, had to succeed with the first few flashbulbs or abandon their use. On Obersalzberg before the war a large tree was planted on the spot where Hitler took march-pasts in summer. Since he wanted to appear bare-headed without a sun canopy, and the tree was the only way.

Chapter 2

Hitler the Architect

AFTER OTTO MEYER9 AND Karl Krause10 had been dismissed by Hitler in April 1938 and during the Polish campaign, respectively, and returned to their units, the field was left to me, a person of few words, reserved and dour, to slip automatically into a position that extended well beyond my original employment as Hitler’s butler. In the course of time I was entrusted with ever more responsibilities, and by the end of July 1944 with the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer11 was finally Head of the Personal Service to the Führer.12 In this role I had to be in constant attendance to Hitler, accompany him on his travels and be responsible for the maintenance of his accommodation. The servants, officers’ mess orderlies, Hitler’s caterers and everybody whose duties were in some way concerned with Hitler’s care were subordinated to me.

When taking up a new post, one obviously keeps one’s eyes and ears open. I made cautious enquiries to determine what was important and unimportant. It was important, as I quickly learned, to observe the demarcation lines between the individual members of ‘court’: ‘Everything else’, I was informed, ‘you have to find out for yourself.’ And so it was. Whenever somebody mentioned anything personal about the Führer I had to be alert to it, for this was my work territory. Hitler, a master in ‘selling himself’, encouraged me to ‘come out of my shell’ and so smoothed the way for me that I quickly lost all the shyness which had intimidated me not only in my relations with him but also with other important Reich celebrities.

That I should expect surprises day in, day out went with the job, for beyond his stereotyped customs Hitler could act unpredictably. Erich Kempka’s predecessor Julius Schreck told me about an incident involving Hitler which illustrated the type of thing that could occur. Schreck was driving Hitler to the Pfalz in the Mercedes with the usual convoy following. On a main highway they passed two RAD13 youths walking to the next town. They thumbed a lift, not realising who was in the Mercedes. Hitler told Schreck to stop and called the two youths over. ‘Their eyes nearly popped out,’ Schreck said, ‘here in the middle of nowhere, the Führer.’ Hitler invited them to climb in and chatted with them as they drove. When dropping the pair off Hitler mentioned that it looked like rain, they should keep their capes handy. One replied that he had been unemployed so long he had not been able to afford one. At once Hitler put his own trenchcoat over the boy’s shoulders and drove on. For those present it was an effective propaganda event shortly after the seizure of power, but for those responsible for Hitler’s wardrobe it was a cause for annoyance. A new coat had to be procured quickly. It had to look like the last one, fit him and be available immediately. I realised that if possible I should always have with me at all times on these travels spectacles, magnifying glasses, colour writing implements and writing utensils, spare shoes, boots, socks, uniform trousers, ties, shirts, gloves, caps and hats for any emergency.

Visitors often told me that it took their breath away when Hitler looked them in the eyes. He never had this effect on me, however. His eyes, described thousands of times as ‘weird’, fascinating, even hypnotising, never impressed me. Obviously I could not look away any time he happened to fix his gaze on me but I was never ‘transfixed’. To the frequently asked question what ‘the thing’ was that compelled everybody to kowtow to Hitler, I have to say I have no idea. He was my boss. I cannot even say the boss of my boss, for I had no other. Nobody, not even Himmler or Bormann, was authorised to give me orders. That, and simply his personality, bound me to him, not to a world-...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- Preface

- Author’s Introduction

- Chapter 1 - I Join Hitler’s Staff: Elser, the Admired Assassin

- Chapter 2 - Hitler the Architect

- Chapter 3 - Hitler on Diet and the Evils of Smoking

- Chapter 4 - Eva Braun, the Question of Sexual Morality, and Equestrian Pursuits

- Chapter 5 - The Berghof

- Chapter 6 - The Reich Chancellery, Bayreuth, the Aristocracy and Protocol

- Chapter 7 - Hitler’s Speeches and the Problem of Göring

- Chapter 8 - Goebbels – The Giant in a Dwarf ’s Body

- Chapter 9 - Himmler and Bormann

- Chapter 10 - Hess’s Mysterious Mission – Was Hitler Behind It?

- Chapter 11 - Other Leading Personalities and the Eternal Stomach Problem

- Chapter 12 - Resolving the Polish Question: September 1939

- Chapter 13 - The Phoney War

- Chapter 14 - The Invasion in the West 1940

- Chapter 15 - The Assassination Attempt of 1944 and Its Aftermath

- Chapter 16 - 1945 – The Last Months of the Third Reich: Reflections on Russia

- Chapter 17 - Hitler’s Suicide

- Chapter 18 - I Flee the Reich Chancellery: Russian Captivity

- Index