- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A "practical and thought provoking" study of the ancient military tactic known as the phalanx—the classic battle formation used in historic Greek warfare (

The Historian).

In ancient Greece, warfare was a fact of life, with every city brandishing its own fighting force. And the backbone of these classical Greek armies was the phalanx of heavily armored spearmen, or hoplites. These were the soldiers that defied the might of Persia at Marathon, Thermopylae and Plataea and—more often than not—fought each other in countless battles between the Greek city-states.

For centuries they were the dominant soldiers of the classical world, in great demand as mercenaries throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East. Yet, despite the battle descriptions left behind and copious evidence in Greek art and archaeology, there are still many aspects of hoplite warfare that are little understood or the subject of fierce academic debate.

Christopher Matthew's groundbreaking work combines rigorous analysis with the new disciplines of reconstructive archaeology, reenactment, and ballistic science. He examines the equipment, tactics, and capabilities of the individual hoplites, as well as how they used juggernaut masses of men and their long spears to such devastating effect.

This is an innovative reassessment of one of the most important early advancements in military tactics, and "indispensable reading for anyone interested in ancient warfare (The New York Military Affairs Symposium).

In ancient Greece, warfare was a fact of life, with every city brandishing its own fighting force. And the backbone of these classical Greek armies was the phalanx of heavily armored spearmen, or hoplites. These were the soldiers that defied the might of Persia at Marathon, Thermopylae and Plataea and—more often than not—fought each other in countless battles between the Greek city-states.

For centuries they were the dominant soldiers of the classical world, in great demand as mercenaries throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East. Yet, despite the battle descriptions left behind and copious evidence in Greek art and archaeology, there are still many aspects of hoplite warfare that are little understood or the subject of fierce academic debate.

Christopher Matthew's groundbreaking work combines rigorous analysis with the new disciplines of reconstructive archaeology, reenactment, and ballistic science. He examines the equipment, tactics, and capabilities of the individual hoplites, as well as how they used juggernaut masses of men and their long spears to such devastating effect.

This is an innovative reassessment of one of the most important early advancements in military tactics, and "indispensable reading for anyone interested in ancient warfare (The New York Military Affairs Symposium).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Storm of Spears by Christopher Matthew in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Hoplite Spear

Any reappraisal of hoplite combat must begin with an examination of the hoplite himself. An understanding of the individual, how he functioned on the battlefield, how he interacted with those around him and how his actions dictated, and were dictated by, the actions of others, forms the foundation of every subsequent enquiry into the broader aspects of warfare in ancient Greece. Similarly, an examination of the individual must also have a reference point from which all further investigations into the characteristics of the hoplite will stem. This starting point must be an examination of what Euripides refers to as the hoplite's only offensive resource: the spear.1 Despite how vital an understanding of the spear's configuration is to the comprehension of how hoplite warfare was conducted, very little analysis of the physical properties of the hoplite's primary weapon has been undertaken by previous scholarship. By examining the available evidence, it is possible to determine the weight of the spear's constituent parts, the overall length of the weapon and, importantly for any examination of the mechanics of hoplite warfare, how the characteristics of the individual parts influenced the functionality of the assembled weapon.

Modern scholarship tends to generalize any reference made to the characteristics of the hoplite spear. In terms of the size of the weapon alone, various estimates have been given ranging from 6–10ft (183cm–305cm) in length.2 While most scholars agree about the presence of the three main constituent parts of the hoplite spear (head, shaft and butt-spike – see following), very little analysis has been done in terms of gauging the average weights of these parts or, more significantly, how the weights of these parts influence the performance of the weapon itself. This may in part be due to the diverse range of somewhat confusing data that is available for such a study.

The ancient texts provide few technical details of hoplite arms and armour. There are no texts that provide elaborate descriptions of hoplite weaponry in the same manner that writers such as Asclepiodotus and Polybius outline for the Hellenistic phalangite and the Roman legionaries of the second century BC.3 From the Archaic Period poems of Tyrtaeus to the Classical Age narratives of Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, many details of the physical characteristics of the hoplite spear, such as its weight or length, are not specified. Later passages by Diodorus and Nepos concerning reforms made to Greek military equipment in the mid-fourth century BC, only offer that the spear was lengthened (by either 50 per cent or 100 per cent according to Diodorus and by 100 per cent according to Nepos), without outlining what the length of the original spear was or to what length it was increased.4

The lack of uniform, or even detailed, information within the available written evidence can be accounted for through an acceptance that the intended audience for many of these written passages were already in possession of an inherent knowledge of the mechanics of hoplite warfare, much of it gained from first-hand experience, which rendered any such information redundant.5 This is clearly illustrated by the aforementioned work of Polybius, which detailed the characteristics of the Roman military for a predominantly Greek audience; who would have had a solid knowledge of Greek weaponry but potentially not of that of their contemporary Romans.

The archaeological record is also a limited, albeit still valuable, resource for any attempt to reconstruct the characteristics of hoplite weaponry. Wood will not survive in the archaeological record except under certain conditions. As a consequence, while many of the metallic components of the hoplite spear have been found, the shaft has, for the most part, been absent. What is certain from the archaeological evidence is that the hoplite spear was tipped with a leaf-shaped head of iron or bronze and had a spike, variously referred to in the ancient sources as a sauroter (σαυρωτήρ), a styrax (στύραξ) or an ouriachos (ούρίαχος), also of iron or bronze, mounted on the rear end of the shaft.6

While artistic representations of the hoplite can sometimes confirm the presence of the leaf-shaped head and sauroter on the weapon carried by the hoplite, the quality of the imagery is dependent upon the artistic style and talent of the artist, the amount of room that the artist had to work within his respective medium and the scale of the image. Factors such as these make it difficult to examine the characteristics of the hoplite spear based solely on the artistic record. This evidence can only be used in conjunction with the archaeological and/or written records. Nevertheless, by examining the individual constituent parts of the spear's construction and how, when assembled, these individual items influence the dynamics of the weapon, the fundamental details of how the spear was designed to be used can be determined.

The head of the hoplite spear

It is no easy task to attempt to distinguish a series of ‘average’ characteristics for the head that was attached to the hoplite spear due to the number of different styles found within the archaeological record. Snodgrass, in his examination of Greek armour and weapons, classifies spearheads into fourteen different categories based upon their size, shape, the material they are constructed from and their period of use.7 Among these classifications, Snodgrass refers to the ‘J style’ spearhead as the ‘hoplite spear par excellence’.8 The ‘J style’ spearhead is typified by its long socket, its long, narrow, blade, and its sloping shoulders. This type of spearhead saw service in warfare from the late geometric period (c.700BC) onwards.9 While perhaps not the most common form of spearhead (a distinction probably belonging to those of the smaller ‘M style’, which had a period of use from the early Protogeometric Age (c.1000BC) to the fall of the Roman Republic (c.31BC)), the ‘J style’ spearhead is, according to Snodgrass, the style that set the standard as the best type to be used by the hoplite.

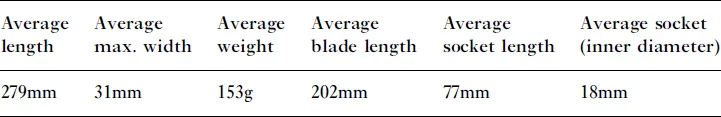

Finds of iron ‘J style’ spearheads at Olympia average 279mm in length, 31mm in width, and have an average weight of 153g.10 Many finds of spearheads at other locations also seem to fall within the parameters set by the ‘J style’. Spearheads excavated from Vergina, some of which Connolly dates to the Greek Dark Age (c.1200–800BC), measure 270–350mm.11 A damaged spearhead excavated from Corinth measures 175mm in length but it is estimated that it would have been approximately 200mm when undamaged.12 A spearhead excavated from Olynthus measures 147mm in length. However, two-thirds of its socket is missing and the length of the complete artefact is estimated at 250mm.13 The longest spearhead excavated from Olynthus, which has been dated to the Classical Era, has a length of 290mm; the smallest complete specimen measures 93mm.14 In his initial reports, Robinson classified these heads as coming from sarissae (the long Macedonian pike), however the length of the larger heads makes it more probable that they belong to spears.15 Unfortunately, many of these artefacts are not categorized under one of Snodgrass' classifications, nor is sufficient detail provided to classify them, and any comparison with the style of spearhead set by Snodgrass can only be based upon relative length.

The head was attached to the shaft through the use of a tubular socket into which one end of the shaft was inserted. Some examples of spearheads contain a single transverse hole in the wall of the socket where a nail or rivet would have been used to secure the head to the shaft. Other examples of spearheads do not possess this hole and must have been secured to the shaft through the use of some form of adhesive. Sekunda suggests the use of pitch.16

Anderson simply summarizes the variance in the available evidence by stating that there is no standard size for the head of the hoplite spear, which ranged in length between 20cm and 30cm.17 Everson states that spearheads in the ninth and eighth centuries BC ranged between 30cm and 50cm in length but that these weapons were almost certainly for throwing.18 Everson later states that spearheads did not change in size from the sixth to the fifth century BC without actually outlining the size that the sixth century weapons took.19 Based upon the work of Snodgrass, the average dimensions of the ‘hoplite spear par excellence’ can most easily be based upon the finds from Olympia. From these finds the ‘average’ characteristics of the iron hoplite spearhead can be set as follows (table 1).

Table 1: The average details of ‘J style’ spearheads at Olympia.

The sauroter

Similar problems are encountered when attempting to distinguish an ‘average’ set of characteristics for the sauroter – the large ‘spike’ on the rear end of the spear. Like the spearhead, many modern works provide only a generalized reference to the shape and/or size of the sauroter. Hanson, for example, states that the sauroter ranged in size between 5cm and 20cm.20 Anderson likewise provides a range of up to 40cm in length.21 Snodgrass states that the size of the sauroter was ‘no less than 40cm’.22

The most common shape of the bronze sauroter is a solid pyramidal or conical spike (referred to hereafter as the ‘long point’). Other examples possess either a ‘short point’ or a ‘small knob’. The base of the common ‘long point’ measured between 20mm and 30mm across at its widest point. It was mounted onto the shaft by a tubular socket approximately 19mm in diameter, designed to fit onto the end of the shaft. Like the spearhead, in some cases, a single rivet passed through a transverse hole in the socket in order to se...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- List of Plates

- Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Hoplite Spear

- Chapter 2: Wielding the Hoplite Spear

- Chapter 3: Spears, Javelins and the Hoplite in Greek Art

- Chapter 4: Bearing the Hoplite Panoply

- Chapter 5: Repositioning the Spear in ‘Hoplite Drill’

- Chapter 6: The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Hoplite Spear

- Chapter 7: The ‘Kill Shot’ of Hoplite Combat

- Chapter 8: Endurance and Accuracy when Fighting with the Hoplite Spear

- Chapter 9: The Penetration Power of the Hoplite Spear

- Chapter 10: The Use of the Sauroter as a Weapon

- Chapter 11: Conclusion: The Individual Hoplite

- Chapter 12: Phalanxes, Shield Walls and Other Formations

- Chapter 13: The Hoplite Battle: Contact, Othismos, Breakthrough and Rout

- Chapter 14: Conclusion: The Nature of Hoplite Combat

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates