- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

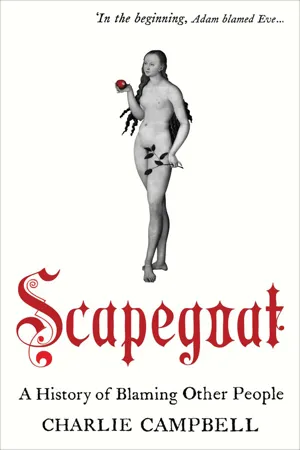

About this book

A "brief and vital account" of humanity's long history of playing the blame game, from Adam and Eve to modern politics—"a relevant and timely subject" (

The Daily Telegraph).

We may have come a long way from the days when a goat was symbolically saddled with all the iniquities of the children of Israel and driven into the wilderness, but has our desperate need to absolve ourselves by pinning the blame on someone else really changed all that much?

Charlie Campbell highlights the plight of all those others who have found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, illustrating how God needs the Devil as Sherlock Holmes needs Professor Moriarty or James Bond needs "Goldfinger."

Scapegoat is a tale of human foolishness that exposes the anger and irrationality of blame-mongering while reminding readers of their own capacity for it. From medieval witch burning to reality TV, this is a brilliantly relevant and timely social history that looks at the obsession, mania, persecution, and injustice of scapegoating.

"A wry, entertaining study of the history of blame . . . Trenchantly sardonic." — Kirkus Reviews

We may have come a long way from the days when a goat was symbolically saddled with all the iniquities of the children of Israel and driven into the wilderness, but has our desperate need to absolve ourselves by pinning the blame on someone else really changed all that much?

Charlie Campbell highlights the plight of all those others who have found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, illustrating how God needs the Devil as Sherlock Holmes needs Professor Moriarty or James Bond needs "Goldfinger."

Scapegoat is a tale of human foolishness that exposes the anger and irrationality of blame-mongering while reminding readers of their own capacity for it. From medieval witch burning to reality TV, this is a brilliantly relevant and timely social history that looks at the obsession, mania, persecution, and injustice of scapegoating.

"A wry, entertaining study of the history of blame . . . Trenchantly sardonic." — Kirkus Reviews

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Scapegoat by Charlie Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia social. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE SEXUAL SCAPEGOAT

‘But now the woman opened up the cask,

And scattered pains and evils among men.’

And scattered pains and evils among men.’

Hesiod

The witch hunts of the Middle Ages and afterwards are one of the most spectacular and disturbing examples of blame being misdirected onto the vulnerable. They were driven by a need to find those responsible for small local tragedies (the death or illness of a child or livestock, or any domestic accident), at a time when it was feared that the Devil lurked behind every mishap. The religious instability of the time provided a fertile environment for this persecution, as communities purged themselves of their least respected and economically valuable members, with the full encouragement of the authorities. A mass wave of scapegoating swept through Europe as tens of thousands of women (and some men) were accused of witchcraft and burned, hanged or drowned. A fear of witchcraft was nothing new however, and the real causes for this misogyny lay much deeper, in the very earliest mythologies, enshrined in the stories of creation.

The ancients believed that we originally existed in a state of purity, and for some, this meant a world without women. According to Greek mythology, men had lived side by side with the gods, free from pain and labour and disease. Woman was an afterthought, as she was in the Bible. Pandora was only sent by Zeus as a punishment to men, after Prometheus had stolen fire from the gods, and as an accompaniment to his entrails being pecked at daily by vultures before regrowing overnight. Pandora brought with her a large jar which she was told never to open, but she did, and so released all the evils in the world. Since then mankind has been condemned to work, grow old, weaken and finally die. This story was first written down by Hesiod in the eighth century BC and its message is echoed elsewhere in Greek mythology – from the Furies and the Gorgons to Scylla and Charybdis (who were both originally sea nymphs), Circe, Medusa and Medea. All reinforce this original expression of feminine evil.

The goddess Atë was responsible for infatuation as well as mischief, delusion and blind folly. She was the daughter of Zeus and Eris, the goddess of strife. Atë was thought to have triggered the Trojan War by turning up uninvited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (though some versions have it that Eris provoked the Judgement of Paris). There, she encouraged Hera, Aphrodite and Athena to fight over a golden apple inscribed ‘For the Fairest’.25 The argument went on and on, and in the end Zeus sent them to a shepherd, Paris, for his verdict. Hera offered him Europe and Asia to rule, while Athena promised him the gifts of wisdom and war, and Aphrodite the prize of the most beautiful woman in the world – Helen, wife of Menelaus. Paris duly chose Aphrodite as the fairest, and gave her the apple. And so Helen fell in love with him, and they fled to Troy together, with all the tragedy that came after.

Atë was also later thought to have caused Achilles’ argument with Agamemnon, who blamed her for his infatuation with the girl he had taken from Achilles. Euripides wrote:

Delusion, the eldest daughter of Zeus: the accursed

Who deludes all and leads them astray …

… took my wife away from me.

She has entangled others before me.

However, in his final plays Euripides allowed that evil and stupidity could not be attributed solely to external causes, to goddesses such as Atë or the intervention of another being. Instead, evil resides at our core and that must be confronted.

After Pandora came Helen of Troy as the focal point of Ancient Greek misogyny. Famously she was blamed for the bloodshed of the Trojan War; it was her beauty that provoked it, not Menelaus or the Greek leaders who supported him. Ultimately, her husband had to get her back partly because his kingship depended on it. Another version had it that Zeus used Helen to cause a war to thin out a population that was threatening to become unmanageable. Euripides wrote in his play about Helen that Zeus ‘might lighten mother earth of her myriad hosts of men.’

As their mythology testifies, this fear of women was endemic to Greek society. In Athens in the sixth century BC, women had the legal status of children, just as, in early Jewish law, women were not regarded as fit witnesses for legal matters. It is ironic that, according to the three Gospel accounts, the resurrection of Jesus was only witnessed by women. Greek women were mostly confined to their own part of the house and were given no formal education. No Athenian citizen was allowed to enslave another but there was an exception that a father could sell his unmarried daughter into slavery should she lose her virginity before marriage. A child was thought to have reached its full potential by being born male, whereas baby girls were ‘mutilated’ versions of the male, according to Aristotle. He believed that women were inferior to men – they did not go bald, so were more childlike, and also had fewer teeth. The twentieth-century British philosopher Bertrand Russell commented of this, ‘Aristotle would never have made this mistake if he had allowed his wife to open her mouth once in a while.’ Meanwhile, the Greek playwright Menander wrote in the third or fourth century BC: ‘He who teaches letters to his wife is ill advised: he’s giving additional poison to a snake.’

The snake is also, of course, central to the Christian creation myth of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. There, too, woman’s disobedience caused us to fall from grace. Eve, like Pandora, disobeyed: ‘The serpent did beguile me and I did eat.’ In doing so, she awoke man to the misery and hardness of life, and for that she has not been forgiven. Over the centuries, male leaders have used the myth that woman’s disobedience is to blame for the world’s ills to justify their patriarchal power. Mesopotamian and Celtic myths did not contain an equivalent of the Fall of Man – an Eve or Pandora figure – but it was the Greek and Christian traditions that most shaped Western attitudes towards women. These asked man to believe that he sprung up fully formed and independent of woman. And Christianity led the way. While Jesus’ attitude towards women was new and enlightened, showing far more compassion and respect to them than was usual at the time, the Old Testament is full of blame and misogyny. In Ecclesiastes it is written: ‘From a garment cometh a moth, and from woman wickedness.’26

This should not be that surprising. Christianity is, after all, a religion with an unusually severe attitude towards sex. The Church was run by men, and so it blamed women. It does not accept its central female figure as a sexual one, casting her as a virgin. It demands celibacy from its priests however that may pervert the sexuality of some of them. And it is only beginning to allow the role of contraception as a way of preventing the spread of AIDS in Africa. Adherence to these strictures dates back to the writings of St. Augustine and other early Christian leaders – the ideas of the fourth century AD still sold to a populace in the early twenty-first century.

Eve was vilified by these leaders, but not in the Bible. They made her responsible for the fall of man, for his expulsion from Eden.27 Tertullian wrote of woman:

You are the devil’s gateway; you are the unsealer of that forbidden tree; you are the first deserter of Divine Law. You are she who persuaded him whom the devil was not valiant enough to attack. You destroyed so easily God’s image, man.

Tertullian did not blame the Jews or the Romans for the death of Christ; instead, he blamed the female sex. This all led towards the theory of original sin, which held that the Virgin Mary was the only human other than Jesus to be free from it. The only way in which women could hope to follow, even to emulate, her was through chastity.

Not even chastity could save a woman who stood out. Hypatia was born in Alexandria between AD 350 and 370, and is one of the most exceptional women in history. She was proficient in (and taught) philosophy, geometry and astronomy, surpassing the philosophers of her time. She was also admired for her character. Allegedly, when one of her smitten students exposed himself to her, she presented him with her bloodstained underwear as a way of dousing his passion. The local Christians resented her, despite her obvious gifts and virtue, and soon saw an opportunity to bring her down through blame.

Bishop Cyril of Alexandria had roused a mob against the local Jews, urging them to sack their homes and turn their synagogues into churches. When the Imperial Prefect objected, the crowd not only attacked him, but accused Hypatia of having bewitched him into supporting the Jews. Her intellectual and musical accomplishments were seen as clear signs that she was a witch, and so one of Bishop Cyril’s followers led a mob to her academy. They dragged her to a church, stripped her and, according to some accounts, skinned her with broken tiles and oyster shells. Then they burned her remains. Her murderers were never prosecuted, and Cyril, who had set all of this in motion by denouncing her in a sermon, rose higher and higher in the Church, eventually being canonized. It remains one of the most shameful episodes in Christian history. But the attitudes behind it are not unique. One of the reasons for the persecution of the Cathars28 was their ‘heresy’ of allowing women to play a more prominent part in society. Denied worldly influence, the only great powers that women were credited with at this time were supernatural ones.

From the fifth century to the fifteenth, witchcraft was widely thought to exist.29 It might be difficult for the modern mind to comprehend, but this belief was deeply ingrained and widespread. Nothing was ever seen to have happened by chance and almost everything bad that took place was the result of witchcraft. Just occasionally misfortune was God’s punishment for our sins, but more often than not it was the work of some neighbouring hag. They were the intermediaries between laymen and the Devil, the evil counterpart to the priest. They had plenty of assistance in their foul deeds. It was thought that the earth was overrun by demons, and their number was added to by the souls of wicked men and women, and of stillborn children. Male demons were incubi, female ones succubi. They could make themselves lovely or hideous. According to the fifteenth-century Dutch scholar Johann Weyer, there were 7,405,926 of them, divided into 72 battalions, each led by a prince or a captain. It was possible to breathe these demons in, and so they could get lodged in your body and thus cause illness and pain.

Witchcraft was a collective endeavour; instead of individual witches running around casting spells, oblivious to each other, there was a shared ethos, with rituals and nightly meetings, or Sabbaths. It was this idea of an overall plot that gave the witch hunt such power and impetus. The witch hunters were looking for the enemy within, rather than finding an external hate figure, though he existed in the form of the Devil. He was not allowed to influence man directly and so used these intermediaries to test the souls of men. Rid the world of witches, the thinking went, and you reduced the spread of evil.

For the anti-witch inquisitors, feminine carnality was at the heart of witchcraft, spreading and compounding our original sin. At their Sabbaths, the witches would regularly meet and have sex with the Devil. There was always a great deal of curiosity about this – was sex with him more enjoyable than sex with a man? The confessions of suspected witches (often under torture) became ever more lurid in their descriptions of the unholy member, which was like that of a mule or a man’s arm and uncomfortably cold (most of what was known of the Devil was information extracted, and shaped, by torture). The Sabbaths would take place at a crossroads or by a lake, leaving the ground all scorched afterwards. In France and England, witches rode broomsticks to get there; in Italy and Spain the Devil carried them, having assumed the form of a goat, which was his favourite shape. And it was as a goat that he would host the Sabbath. The witches and wizards would dance until they collapsed, then any newcomers would kiss the goat’s hindquarters, deny their salvation and spit on the Bible. They would recount their sins, and if they hadn’t committed enough would be reprimanded by the Devil who would flog them with thorns or a scorpion. Then proceedings might be rounded off with a dance of toads while the Devil played the bagpipes.

Witches were believed to target fertility above all else, whether it be in humans or crops. For so much of history, procreation has been a relative mystery, and a favoured explanation for its failure was the ugly old woman coming between the beautiful young lovers. She could do so in surprising ways. According to the Malleus Maleficarum (of which more later) witches often stole penises, ‘in great numbers, as many as 20 or 30 together, and put them in a bird’s nest or shut them up in a box, where they move themselves, like living members, and eat oats and corn.’ As proof of this, the authors offered the following story: ‘A certain man tells that, when he lost his member, he approached a certain witch to ask her to restore his health. She told the afflicted man to climb a certain tree, and that he might take whichever member he liked out of a nest in which there were several members. And when he tried to take a big one, the witch said, “You must not take that one,” adding, “because it belonged to a parish priest”.’ Here, an old anti-clerical joke was adopted as anti-witch propaganda.30

Up until the early fourteenth century, accusations of witchcraft tended to be made by members of the political classes against each other as they jostled for power. In 1317, Pope John XXII had a French bishop burned at the stake, accused of using witchcraft in a plot against him. King Edward II also claimed that his political enemies used witchcraft against him. The common people were rarely affected by such concerns. But witchcraft was a charge that was so easily brought and so hard to refute that the powerful could use it against their enemies whenever they wanted to crush them and had no firm crime to pin on them. It was used as a pretext for the violent persecution of individuals and communities whose real transgressions were entirely political or religious.

A prominent example of this was the extermination of the Stedinger in 1234. They had lived peacefully with a remarkable degree of civil and religious freedom, but found themselves harassed by the Archbishop of Bremen, among others. They refused to pay the taxes and tithes demanded of them and rose up to drive out their oppressors. Eventually the archbishop appealed to Pope Gregory IX for help. But the first invasion was repelled. The pope called for a crusade to put down this den of iniquity, accusing the Stedinger of witchcraft, devil worship and the usual litany of crimes. A great army was raised on the back of this, and the rebels were defeated. A similar process was used against the Templars (who were accused of child murder, sodomy, etc.) between 1307 and 1313. They too were exterminated (there was also a financial imperative here; the French kings seized the Templar wealth). The thirteenth century had seen great outbreaks of religious fervour – including the Flagellants who marched from town to town in their bloodstained processions – and these extreme sects could turn against the Church as much as they could be absorbed by it. So there was a need, more than ever, for the Church to find a common enemy.

The arrival of the Black Death and its spread across Europe made this all the more urgent. At least 30 per cent of the population in Europe would die of this plague, which killed an estimated 25 million victims. Jews were the first to be blamed for its arrival, and many of their communities were exterminated by vengeful mobs. Muslims and lepers were also held responsible. The witch craze was beginning to take root, and witches would be added to the Catholic Church’s roster of useful scapegoats as they exhausted the others, quite literally, by exterminating them. Previously there had been incidents of witchcraft and subsequent trials, but no systematic campaign to deal with witches. It took the Church’s involvement to achieve this. The fourteenth century was – like the fifth century BC in Greece and the third century AD in Rome – a time of calamity, of plagues and wars, when fear and uncertainty were rife. New forms of belief challenged the once omnipotent Church and its monopoly on truth. It was no time to be out of the ordinary, particularly as a woman. For the next couple of centuries the witch craze ran freely. There would be so many trials for witchcraft that other crimes were overlooked. And the more witches the authorities burned, the more they found to burn.

At the fore in the witch hunt were two Dominican Inquisitors, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. They had convinced Pope Innocent VIII of the very real threat posed to the Church and to civilization by witchcraft, and so obtained almost unlimited powers from him. In 1484 Kramer had been investigating a case in Ravensburg, in Germany. Eight women were due to face trial, accused of ‘causing injury to people and animals, and for raising “tempests” to destroy the harvest.’ Subsequently over 20 witches were burned at the stake. Afterwards he moved east with his witch-hunters but met with different treatment in Innsbruck. There the bishop considered Kramer senile and dangerous, and set the accused witches free. So Kramer and Sprenger sought more power from the pope.

Later that year Innocent VIII issued a papal bull declaring open season on witches:

And at the instigation of the Enemy of Mankind they do not shrink from committing and perpetrating foulest abominations and filthiest excuses to the deadly peril of their own souls … Wherefore we … decree and enjoin that the aforesaid inquisitors [Kramer and Sprenger] be empowered to proceed to the just correction, imprisonment, and punishment of any persons, without let or hindrance, in every way …

Sprenger was alleged to have burned over five hundred witches in a single year, yet was also the founder of the Confraternity of the Holy Rosary, set up to honour the Virgin Mary. He and Kramer were most famous for the book they wrote together, the Malleus Maleficarum (known also as the ‘Hammer of the Witches’). This became one of the most read books of the time and is probably the most misogynistic text ever published. It first came out in 1486 and, like the Bible, it benefited from the new technology of the printing press for its success; there were 13 different Latin editions in print by 1523, 15 German editions printed up to 1700 and 11 French. Its principal message was that witches, having struck a pact with the Devil, were responsible for all misfortunes, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Prologue

- Introduction

- The Word ‘Scapegoat’

- The Ritual Scapegoat

- The King and the Scapegoat

- The Christian Scapegoat

- Christ the Scapegoat

- The Jewish Scapegoat

- The Sexual Scapegoat

- The Literal Scapegoat

- The Communist Scapegoat

- The Financial Scapegoat

- The Medical Scapegoat

- The Conspiracy Theory

- Alfred Dreyfus

- The Psychology of Scapegoating

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Acknowledgements