This book is available to read until 15th November, 2025

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 15 Nov |Learn more

About this book

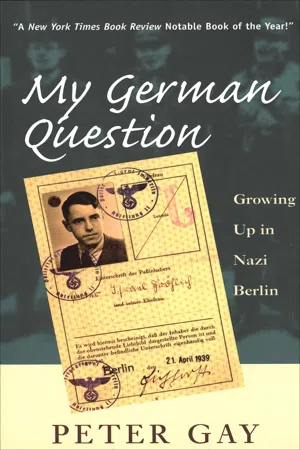

"Not only a memoir, it's also a fierce reply to those who criticized German-Jewish assimilation and the tardiness of many families in leaving Germany" (

Publishers Weekly).

In this poignant book, a renowned historian tells of his youth as an assimilated, anti-religious Jew in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1939—"the story," says Peter Gay, "of a poisoning and how I dealt with it." With his customary eloquence and analytic acumen, Gay describes his family, the life they led, and the reasons they did not emigrate sooner, and he explores his own ambivalent feelings—then and now—toward Germany its people.

Gay relates that the early years of the Nazi regime were relatively benign for his family, yet even before the events of 1938–39, culminating in Kristallnacht, they were convinced they must leave the country. Gay describes the bravery and ingenuity of his father in working out this difficult emigration process, the courage of the non-Jewish friends who helped his family during their last bitter months in Germany, and the family's mounting panic as they witnessed the indifference of other countries to their plight and that of others like themselves. Gay's account—marked by candor, modesty, and insight—adds an important and curiously neglected perspective to the history of German Jewry.

"Not a single paragraph is superfluous. His inquiry rivets without let up, powered by its unremitting candor." — Los Angeles Times Book Review

"[An] eloquent memoir." — The Wall Street Journal

"A moving testament to the agony the author experienced." — Chicago Tribune

"[A] valuable chronicle of what life was like for those who lived through persecution and faced execution." — Choice

In this poignant book, a renowned historian tells of his youth as an assimilated, anti-religious Jew in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1939—"the story," says Peter Gay, "of a poisoning and how I dealt with it." With his customary eloquence and analytic acumen, Gay describes his family, the life they led, and the reasons they did not emigrate sooner, and he explores his own ambivalent feelings—then and now—toward Germany its people.

Gay relates that the early years of the Nazi regime were relatively benign for his family, yet even before the events of 1938–39, culminating in Kristallnacht, they were convinced they must leave the country. Gay describes the bravery and ingenuity of his father in working out this difficult emigration process, the courage of the non-Jewish friends who helped his family during their last bitter months in Germany, and the family's mounting panic as they witnessed the indifference of other countries to their plight and that of others like themselves. Gay's account—marked by candor, modesty, and insight—adds an important and curiously neglected perspective to the history of German Jewry.

"Not a single paragraph is superfluous. His inquiry rivets without let up, powered by its unremitting candor." — Los Angeles Times Book Review

"[An] eloquent memoir." — The Wall Street Journal

"A moving testament to the agony the author experienced." — Chicago Tribune

"[A] valuable chronicle of what life was like for those who lived through persecution and faced execution." — Choice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access My German Question by Peter Gay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

FOUR

Mixed Signals

Nature and my parents seem to have prepared me well for the hazards of daily life under the Nazis. I had blue eyes and a straight nose, brown hair and regular features—in short, like my parents, I did not “look Jewish.” I had a peculiar obsession in those days: when I saw myself in the mirror, I judged my appearance to be just as it should be, while others, like my somewhat pudgy cousin Edgar, with his curly hair, fell off from the standard I set—a case of boyish narcissism, perhaps (I am ashamed even to think this) fed by the official propaganda touting the Teutonic looks that were, according to Nazi ideology, the ideal. I, too, looked as German as any. And my upbringing seemed almost intentionally aimed at having me escape particular notice, whether on the street, in a department store, or at a soccer stadium. I was composed and polite, and did not invite attention.

On a deeper level, too, I was ready, though of course I was quite ignorant of this at the time. Having learned to banish from awareness, or at least to control, my rage, I was not about to make uncalled-for remarks or even faces at fluttering black-red-and-white flags adorned with the swastika or the sordid spectacle of brownshirts marching down Berlin’s streets as though they owned them—as, of course, they did after January 30, 1933. I was exposed to such exhibitions nearly every day: the Nazis were adroit at political theatre. They even uprooted the venerable linden trees lining the city’s most distinguished avenue, Unter den Linden, to make more room for displays of flags and uniformed marchers. I had been well trained to show no reaction, make no comment. Not that I was trying to pass; I was born to pass.

The advent of the Third Reich is a blank in my mind—a conspicuous instance of repression at work. After all, my parents and my wider family must have talked about the Nazis’ bid for power every day, and anxiously; certainly the press was full of it. But my first firm memory of that period dates from February 28, four weeks after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor: a large photo showing smoke billowing over the roof of the Reichstag. That vast pile, dating from the late nineteenth century, had been set on fire the day before. A young, not very bright Dutch Communist named Marinus van der Lubbe was quickly arrested and confessed to having committed the arson on his own.

The story was unbelievable. Years later, when I was working on the history of the Weimar Republic and its pathetic end, I read in the much-quoted diary of Harry Graf Kessler, aesthete, patron of the arts, and principled anti-Nazi: “This ca. twenty-year-old is supposed to have distributed inflammable material in more than thirty places and set them alight without anyone’s noticing his presence or activity or his carting in all these massive amounts of material.” Kessler did not believe the story put out by the controlled press, nor did my parents: surely Goring had set the fire for political reasons, to supply his fellow gangsters with a convenient excuse for terrorizing whatever opposition remained. They talked knowingly about a secret tunnel leading to the Reichstag basement, through which the arsonists had carried the supplies they needed to start this convenient conflagration.

With characteristic dispatch and raw efficiency, the Nazis tightened their grip on power, mixing cajolery with lies, threats, and violence. The Reichstag fire provided them with apparently good reasons for pushing through an emergency decree, beating up journalists, politicians, and ordinary citizens known to be insufficiently supportive, arresting opposition leaders, forcing intellectuals into exile, and mobilizing public opinion with a propaganda machine of unprecedented intensity. In light of this politics of brutality and seduction and the laming of all independent opinion, the elections to the Reichstag of March 5 were scarcely the triumph that the regime’s spokesmen proclaimed them to be: the Nazis secured just under 44 percent of the vote. Had it been a free election, that figure would have been significantly lower. But this did not stop them; on March 23, the Reichstag voted an enabling act that essentially handed its powers to the Hitlerian regime.

It was not to be expected that Germany’s new masters would overlook the Jews. On April 1 they staged a countrywide boycott of Jewish stores, lawyers, and physicians. Brownshirts and black-shirted S.S. men, posted at strategic spots, “warned” potential customers and clients against patronizing Jews—not Germans. Enormous posters plastered on walls and kiosks proclaimed, “The Jews of the whole world want to destroy Germany! German Volk! Defend yourself! Do not buy from Jews!” Certainly in Berlin this “action” was not much of a success. But what bodily threats and inflammatory slogans did not accomplish, servile institutions managed with ease.

Professional organizations hastened to expel “non-Aryan” writers and newspapermen, while orchestras and theatres dismissed conductors, directors, and performers they judged to be racially ineligible or politically tainted. The Jewish professors’ turn came soon after, while Jewish executives in banks, commerce, and industry were prematurely pensioned. On April 7 a comprehensive Civil Service Act excluded Jews from all public employment. The exodus was well under way. For the fortunate few, like Franz Neumann, the decision to flee to freedom was forced on them. For less well-prepared men like my father, with no foreign languages or other portable specialty, the situation was less clear-cut and the prospects exceedingly obscure. They were complicated further by the mixed signals that were all we had to go on.

My admission to gymnasium and my years there were one long demonstration of these signals at work. In the spring of 1933 the larger new world and my own small corner of it intersected. I had successfully completed four years of elementary education, and unlike working-class boys, who would continue in their free school for four more years, I, with other young bourgeois, was destined for more elevated secondary schooling, costing my parents twenty marks a month. There were distinct types of gymnasia in the Germany of my childhood, ranging from the classical version, which had retained Greek in its curriculum, to more modern real-gymnasia, oriented toward nonacademic careers. The Goethe-Real-Schule for which I was headed was of the second type: it started ten-year-olds with French and after two years offered a choice between two tracks, one starting Latin and the other English. Though relatively progressive, it was traditional enough to call its classes by Latin numerals, some of them oddly yoked to German prefixes: Sexta, Quinta, Quarta, Unter-Tertia, Ober-Tertia, and the rest.

During the Weimar Republic, my admission to a gymnasium would have been a matter of course; my parents’ class and my grades would have guaranteed it. Now, though, a newly proclaimed policy restricted the numbers of Jewish boys to be accepted. Their percentage was not to exceed the percentage of Jews in Berlin’s population—more than 150,000 in four million, just under 4 percent. But a special circumstance exempted me from any quota: my father had been wounded in the First World War, a condition much honored in Germany and one that conferred a certain status on the veteran. In 1915 he had been shot in the right hand and the right upper arm; the scars, pale little rosettes, were still visible. The wounds kept my father from stretching out his arm to full length, though this hardly handicapped him: in the mid-1930s he became a champion bowler. Still, this relatively minor disability was enough to make him the recipient of the Iron Cross Second Class and entitled him to privileges like riding first class on a second-class railroad ticket and receiving a monthly pension. And now, in March 1933, it gave his son an unquestioned place in a gymnasium of his choice.

My father, like most Germans, had greeted the coming of the war in early August 1914 with patriotic enthusiasm, but he soon turned pacifist. I once asked him when he had switched camps. “In September 1914,” he told me, “when I saw my first corpse.” I should add that he threw his pacifist ideals overboard in September 1939, the moment Britain and France declared war against the Axis. Later, after Pearl Harbor, nothing pleased him more than to contribute his German medal to the scrap drive collecting metal for the American war effort. For this gesture his picture appeared in the Denver papers.

For three years, until 1936, when we moved some fifteen minutes farther away, I had a five-minute walk from Schweidnitzerstrasse 5 to the big, solid, airy building that was supposed to be my school for the next nine years. I have a photograph of a class excursion in my third year, with twenty-one students surrounding our Latin teacher, Dr. Rose, bald, bespectacled, corpulent, wearing an old-fashioned suit complete with vest, stand-up collar, and narrow tie. Rose represented the best my gymnasium had to offer me: a teacher of the old school who was neither a martinet nor an anti-Semite. He had grown old with the Goethe-Real-Schule, having taught there since its opening in 1907, and he brought a whiff of the more decent aspects of the Wilhelminian Empire into the postwar and even into the Nazi world.

I recognize my cousin Edgar in that photo, smiling, and at least one other Jewish pupil, named Landsberg, who, I recall, was not the brightest. Two other classmates stand out: Rutkowsky, who looks like a working-class bully (though he never bullied me), with a square face and a pugilist’s flat nose, and, standing with his arm on my shoulder in a comradely gesture, the ash-blond Hans Schmidt. This shows how photographs lie. May his bones lie rotting in Russian soil!

There was something truly repulsive about Hans Schmidt, and that is why he deserves his fifteen seconds of fame here. He was as unathletic as I and more cowardly. The compulsory workouts at the gym were torture to me; I could never leap over the leather-covered wooden horse without a sense of panic, and Hans Schmidt, I like to believe, felt the same way. But while my timidity hurt no one else, Hans Schmidt was more malicious; he aimed to wound without taking responsibility. Whatever anti-Semitic talk there was among my classmates was largely at his instigation, and he incited others to do the dirty work for him, though, if memory serves, often without success.

I remember running into him in my first year at the gymnasium as I was walking with my parents on the Paulsbornerstrasse, which linked us to the other Fröhlich family on the Pariserstrasse; he stopped to talk to us, courteous and respectful. But once he joined the Hitler Jugend, as he quickly did, he sported his uniform and became a little Nazi who had no use for me. In class he had no rivals—I saw to that. He was consistently the best student, the Primus, though I was convinced that I was brighter than he; I simply held back out of prudence, managing to stay in second place. I do not think that I ever explicitly formulated this policy; this act of self-protection had become second nature to me.

The pressure on Jewish pupils at the Goethe Gymnasium was selective: I was never ridiculed, never harassed, never attacked, not even slyly, to the best of my recollection. My cousin Edgar, in contrast, was victimized more than once, threatened with being dragged before a Stürmer display and made to read it. The Stürmer—need I remind anyone?—was the pornographic anti-Semitic weekly edited by Julius Streicher, which featured stories and cartoons depicting savagely caricatured Jews, with repellent curly hair, grotesquely hooked noses, evil eyes, and fat, sensual lips, busy cheating the world, orchestrating hostility to the Third Reich, and, worse, lusting after blonde, often half-naked Aryan women. I do not believe that Edgar was ever put through this trial, but he had every right to be uncomfortable at his school. I find it soothing to recall that Streicher was convicted at the Nürnberg trials and hanged—he is a principal reason that my opposition to the death penalty has always been half-hearted.

For an institution under the Nazis, my school had a remarkably bland, almost unpolitical atmosphere. Its authoritarianism, such as it was, seemed less an obeisance to Hitlerite Germany than a legacy from earlier times. We sat in orderly rows, each of us at an assigned desk that was nailed to the floor, as was the chair. We knew our place and were quite literally unmovable, a situation one might read as a symbol of stability or, doubtless more accurately, of rigidity. The desks themselves were uniform, with a slanting top that could be lifted to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- One: Return of the Native

- Two: In Training

- Three: The Opium of the Masses

- Four: Mixed Signals

- Five: Hormones Awakening

- Six: Survival Strategies

- Seven: Best-Laid Plans

- Eight: Buying Asylum

- Nine: A Long Silence

- Ten: On Good Behavior

- Acknowledgments