eBook - ePub

Available until 15 Nov |Learn more

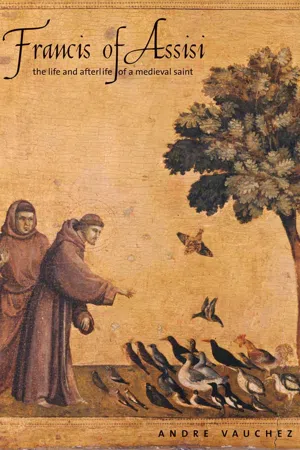

Francis of Assisi

The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval Saint

This book is available to read until 15th November, 2025

- 415 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 15 Nov |Learn more

About this book

A biography of the saint as both mystic and man: "The single best book about Francis now available in English" (

Commonweal).

In this towering work, Andre Vauchez draws on the vast body of scholarship on Francis of Assisi, particularly the important research of recent decades, to create a complete and engaging portrait of the saint. He also explores how the memory of Francis was shaped by contemporaries who recollected him in their writings, and completes the book by setting "il Poverello" in the context of his time, bringing to light what was new, surprising, and even astonishing in the life and vision of this man.

The first part of the book is a fascinating reconstruction of Francis's life and work. The second and third parts deal with the texts—hagiographies, chronicles, sermons, personal testimonies, etc.—of writers who recorded aspects of Francis's life and movement as they remembered them, and used those remembrances to construct a portrait of Francis relevant to their concerns. Finally, Vauchez explores those aspects of Francis's life, personality, and spiritual vision that were unique to him, including his experience of God, his approach to nature, his understanding and use of Scripture, and his impact on culture as well as culture's impact on him.

"Considered one of the great spiritual leaders of humankind, Francis of Assisi was also a man of many faces and personas: ascetic, the founder of a religious order, a romantic hero, a mystic, a defender of the poor, a promoter of peace. But as Vauchez emphasizes—and this biography constantly reminds us—Francis was also a flesh-and-blood human being . . . A bracing, erudite account of a mystic's life." — Booklist

In this towering work, Andre Vauchez draws on the vast body of scholarship on Francis of Assisi, particularly the important research of recent decades, to create a complete and engaging portrait of the saint. He also explores how the memory of Francis was shaped by contemporaries who recollected him in their writings, and completes the book by setting "il Poverello" in the context of his time, bringing to light what was new, surprising, and even astonishing in the life and vision of this man.

The first part of the book is a fascinating reconstruction of Francis's life and work. The second and third parts deal with the texts—hagiographies, chronicles, sermons, personal testimonies, etc.—of writers who recorded aspects of Francis's life and movement as they remembered them, and used those remembrances to construct a portrait of Francis relevant to their concerns. Finally, Vauchez explores those aspects of Francis's life, personality, and spiritual vision that were unique to him, including his experience of God, his approach to nature, his understanding and use of Scripture, and his impact on culture as well as culture's impact on him.

"Considered one of the great spiritual leaders of humankind, Francis of Assisi was also a man of many faces and personas: ascetic, the founder of a religious order, a romantic hero, a mystic, a defender of the poor, a promoter of peace. But as Vauchez emphasizes—and this biography constantly reminds us—Francis was also a flesh-and-blood human being . . . A bracing, erudite account of a mystic's life." — Booklist

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Francis of Assisi by Andre Vauchez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 1182–1226

1

FRANCESCO DI BERNARDONE

A CITY, A MAN: ASSISI AND FRANCIS

Few historical figures have been as associated with a place and, more precisely, with a city than Francis of Assisi. Saint Thomas is “Aquinas” only by virtue of his birth. Saint Bernard, although in principle constrained by monastic stability, was often absent from the abbey of Clairvaux to which his name remains associated. In contrast, Francis is tied to Assisi with every fiber of his being. This is where he was born at the end of 1181 or the beginning of 1182; where he died during the night of the third and the fourth of October 1226; and where he was buried, before his body was transferred—in 1230—to the basilica built in his honor on the western edge of the city. He spent his whole childhood in his native city. And if he often left it after the birth of his fraternity, he was not away from it for very long, except when he went to Egypt and Palestine in 1219–1220. The rest of the time, at the conclusion of his preaching campaigns in central and northern Italy, he always faithfully returned there or, in any case, to the church of the Portiuncula, located about a little more than a mile outside its walls: the cradle of his order, which always remained for him a primary point of reference. Franciscanism is really the only Christian religious movement that might be able to speak of having a capital (Assisi) and a center (Umbria). The imprint which the Poverello has left is nowhere stronger than in those places where he lived and sojourned for a long time.

When Francis came into the world at the end of the twelfth century, what was this city like where his human and religious experience would take root? In his Divine Comedy, Dante admirably evoked its natural surroundings:

Between Topino’s stream and that which flows down

from the hill chosen by the blessed Ubaldo,

from a high peak there hangs a fertile slope;

from there Perugia feels both heat and cold

at Porta Sole; while behind it grieve

Nocera and Gualdo under their heavy yoke.1

from the hill chosen by the blessed Ubaldo,

from a high peak there hangs a fertile slope;

from there Perugia feels both heat and cold

at Porta Sole; while behind it grieve

Nocera and Gualdo under their heavy yoke.1

Assisi was at this time a settlement of moderate importance, less extensive than it is today. For we have to imagine the absence of the basilica of San Francesco and the immense convent to the west of it (which reminds one a little of the Potala of Lhassa in Tibet!), both constructed in the thirteenth century. The city is located in the heart of Umbria, between the Apennine Mountains and the vast plain that extends from Spoleto up to Perugia—an area which, during the Middle Ages, was called the Spoleto Valley. The medieval town was the successor of the Roman municipality upon whose ruins it was built, as is evidenced even today by the temple of Minerva (transformed into a church) on the Piazza del Comune, as well as by a part of its ancient walls and numerous private and public structures, like the ruins of the amphitheater in the upper part of the town. We know very little with precision about the history of Assisi during the Early Middle Ages, though it seems that the city might have begun its rebirth and expansion around the tenth century under the influence—here as elsewhere—of the resident bishop, the canons of the cathedral chapter, and a few Benedictine monasteries in the town, like those of Saint Peter (which had been reformed by Cluny and rebuilt between the end of the twelfth and the middle of the thirteenth century) and of Saint Benedict. On the slopes of Mount Subasio, at the foot of this high mountain, often covered with snow during the winter, hovering above Assisi from a height of more than four thousand feet, are to be found numerous grottoes, like the Carceri, where hermits lived. At the time of Francis, there were eleven monastic establishments for men and seven for women within the city and its immediate environs, in addition to the great neighboring landowning abbeys of Sassovivo and Vallegloria out in the contado, the countryside under the control of the town. In the twelfth century, the two principal religious poles of Assisi were the abbey of Saint Peter, symbol of monastic power, and the cathedral, which had been transferred from Saint Mary Major (the church whose foundation is attributed to Saint Savino in the fourth century) to the church of San Rufino. At San Rufino, in the upper part of the city, the relics of this bishop and local martyr, who died, according to tradition, in 238, had been transferred and placed in an ancient sarcophagus. The structure was completely rebuilt and embellished between 1140 and 1220; its main altar was consecrated by Gregory IX in 1228. It is there, according to tradition, that Francesco di Bernardone—such is the real name of the one we call Francis of Assisi—was baptized in October 1181 or 1182, while the cathedral was under construction, during the episcopacy of Rufino of Assisi, prelate between 1179 and 1185 and author of the important treatise “On the Good of Peace.” These construction projects illustrate the growing strength of the power of the bishop, who possessed sizable landed properties—of which a portion was granted as a fief to lay vassals—and who exercised a considerable influence over the city and its contado.

The town was surrounded by a fortified wall, definitely much smaller than it is today: it extended seventy-five hundred feet around the city by the end of the thirteenth century, already much larger than the Roman wall of five thousand feet celebrated by the poet Propertius at the time of Augustus. Yesterday as today, its houses of pink and white stone of one or two stories clung to the edges of terraces, separated by small walls, and connected to each other by narrow alleyways and winding staircases. On the marketplace and especially in the aristocratic quarter of Murorupto, rose tall house-towers, similar to those that one can still see at San Gimignano or Bologna, where the members of the principal aristocratic clans or families (consorterie) who dominated city life at that time resided. A few main streets rose into the city, on steep inclines, in diagonals from the gates of the city up to a few flat areas made into piazzas, of which the principal ones were the Piazza del Comune, with the façade of the temple of Minerva immortalized by Giotto, and the one that extended out in front of the cathedral of San Rufino. On the summit, outside the city walls, the town was dominated by a fortress perched upon a peak, the “Rocca,” which, in its present state, dates only to the fourteenth century but gives a good idea of what this fearsome bastion could have looked like at the end of the twelfth. Overshadowing the town and the road that led from Perugia to Spoleto, by way of Foligno and the springs of Clitunno, the Rocca occupied a strategic position of the first magnitude.

We do not know the exact size of the population of Assisi at this time. It probably counted scarcely more than three thousand to four thousand inhabitants, since the total population of the diocese, including the countryside, has been estimated at about fifteen thousand by the end of the thirteenth century. Located between the ancient Via Flaminia, which rose toward the Adriatic Coast and down through the Tiber Valley, the city of Francis in the thirteenth century was one step on the road to Rome and to the Holy Land. Indeed, numerous pilgrims went to embark for the East at Ancona in the neighboring Marches, as attested to by the itineraries followed by the monk and chronicler Matthew Paris (1253) and by the archbishop of Rouen, Eudes Rigaud (1254). Several hospices, like the one known as de Fontanellis run by the Crosiers, were there to welcome them.

Like the majority of cities within Italy, Assisi drew most of its revenues from the surrounding countryside. In the period of accelerated demographic and economic expansion that marked the second half of the twelfth century, the relationship between the Umbrian city and the contado, which had been placed under its authority in 1160 by the emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1152–1190), was evolving considerably. The units of production which for centuries had established the great landowning nobility, lay as well as ecclesiastical, were now beginning to fragment through the sale—more or less obligatory—by feudal lords unable to adapt to developments in the monetary economy and to the hike in prices that this entailed. In the mountainous zones that extended north of the city, the clearing of the land was undertaken by a few wealthy Benedictine abbeys, like Saint Benedict of Subasio or Saint Mary of Valfabbrica (which was a dependent of Nonantola in Emilia Romagna). But it was done especially by those elements of urban society that had capital at their disposal and who sought to make it earn more in the most cost-effective way possible. This is the period when the rural countryside surrounding the town— which one could still admire at the beginning of the 1960s—was really establishing itself. Here, fields sown with cereals and rows of fruit trees predominated which, together, constituted the base of agricultural exploitation that is called in Italian coltura promiscua. To the west and to the east, on the watered terraces and the low-lying foothills of the mountains, terraces were created and systems of waterways developed to irrigate the rocky soils on which the new planting of vines and especially olives was going to produce its fruits. To the south of Assisi, between Spello and Perugia, stretched a low and poorly drained plain where the waters of two modest waterways, the Chiascio and the Topino, stagnated. Here peasants pastured their cattle as the raising of livestock expanded at the time, but only a few people actually lived there. Yet it was in this unhealthy zone—where swamp-sickness and malaria were rampant—that Francis and his first companions established themselves at the beginning of their experience of community life: first at Rivo Torto, in a hut from which they were expelled because the owner wanted his mule to stay there, and then next to a little church in terrible shape, Saint Mary of “the Portiuncula,” which the people called Saint Mary of the Angels, built on the ruins of a Roman villa.

The wealth of Assisi and its inhabitants was also due to economic activities proper to the city itself; and there were probably a few textile workshops there already by the year 1200. One must not, however, exaggerate their importance. Before the fourteenth century, Francis’ native town produced barely enough articles for local consumption. And squeezed as it was between the two great commercial cities of Perugia to the west and Foligno to the east, it was never anything other than a second-rate economic center. Nonetheless, side by side with an aristocracy that remained politically and ideologically dominant, there developed an urban middle class that knew how to take advantage of the growth in demand created by a general rise in the standard of living. Not content to just sell the agricultural produce and the products of local artisans, this social group on the rise gave itself over to loans with interest, in spite of condemnations of usury by the Church which were hardly respected but which left in people’s minds a vague feeling of guilt.

The society in which Francis grew up was in many ways more feudal than mercantile. His father, Pietro di Bernardone, was hardly a capitalist, and it would be wrong to imagine him to have been a great businessman, in the manner of a Francesco Datini, the famous merchant of Prato of the fourteenth century. In fact, it does not seem that he was a maker of cloth at all; rather, his activity was that of a seller who, in his shop as well as at markets and fairs, offered clients cloth which he had sought out in places where it was produced or exchanged. His wealth—which one can estimate with a certain amount of precision—consisted partly in cash, deposited or loaned with interest, and partly in revenues from lands out in the contado, but especially from real estate which he had acquired inside of Assisi. Indeed, if local scholars still debate about which house Francis was born in, it is because his father sat atop a comfortable landed patrimony that must have had a good return in this period of demographic growth and rapid increase of the urban population. Thus, son of a rich man and probably of a nouveau riche, very early on Francis acquired a concrete experience of money, whose importance and power in social relationships he could measure.

MERCHANT OR KNIGHT? THE ADOLESCENCE OF A RICH MAN’S SON

It is into this urban environment, then in the process of change, that Francis was born and spent his youth. We are rather well informed about these years by a text drawn up in Assisi during the years 1244–1246 and known as the Legend of the Three Companions. Its author, whose identity escapes us, in spite of the title that it traditionally bears, was born in the same town, whose institutions he knew well. His principal aim was to correct certain details about the life led by the saint before his conversion as it had been described—in terms too general and moralistic—in the first Life of Saint Francis, composed in 1228–1229 by the friar Thomas of Celano.2 According to this source, Francis was first named John by his mother. But when Pietro di Bernardone, whose trade as a cloth merchant had taken him away from Assisi at the moment of the birth, returned home, he demanded that his son be called Francesco—Francis, the “Frenchman”—perhaps because he himself had recently gone to France on business. The anecdote is suspect, inasmuch as certain hagiographers commented on the change of name in order to present Francis as a new John the Baptist, the Precursor come into the world to prepare the way of the Lord. In any case, the choice of the name by which he is known to us was purposeful. Though not absolutely unique, the name was essentially unknown at that time in Italy. And if his father did give it to him, it was probably due to a trend of prizing everything that came from over the mountains. For were not Italian merchants going at that time in search of the heavy, richly colored cloth made in Flanders and Artois—like the famous scarlet cloth so sought after in upperclass circles—at the fairs of Champagne (Provins, Lagny, Troyes, Bar-sur-Aube)?

Indeed, the cultural influence of the France of Philippe Augustus was starting to have a profound effect upon the urban elites of Italy. Like the majority of regions in the West between the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century, Umbria welcomed and enthusiastically adopted the literary expressions and ideals of the knightly epic and courtly poetry. Romances of adventure, chansons de geste et d’amour, were known by all; and their heroes— Charlemagne, Roland, Merlin, Lancelot—were likewise depicted on the entrances and pavements of cathedrals in northern and southern Italy, as one can still see in Modena and Otranto. There is no need to imagine—as many have without any proof whatsoever—that Francis’ mother was French in order to explain the fact, at first surprising, that the young man who became Francis often sang poems in French. In so doing, perhaps he expressed his most intimate feelings or thoughts in the language of those regions north of the Loire where he dreamed about going but where he was never able to go. He certainly had not studied French in his parish school of San Giorgio, where he had received during his childhood a level of instruction that one would today call elementary education. But French was at that time in Italy what English is today: the language in which lyrical and musical culture was expressed, especially appreciated by the young who discovered it through songs and poetry.

We must resign ourselves to not knowing a lot about Francis’ youth. He never mentioned it in his writings, except to say in his Testament that he had lived “in sin” (cum essem in peccatis). His medieval biographers, in line with hagiographical traditions, devoted little attention to these formative years, eager as they were to address the more significant part of his life: his conversion and commitment to the evangelical life.3 We know that he had blood brothers—one of them, Angelo, harshly mocked him after he had abandoned the family home— and that his mother especially cherished him. In the Lives that were consecrated to her son, Pietro di Bernardone is not presented in a flattering light: a “carnal” man, attached to money and his goods, he eventually entered into open conflict with Francis and publicly renounced him for giving away some of those same goods. Numerous painters, of whom Giotto is only the most famous, have immortalized the scene where the newly converted, in the first months of 1206, renounces his father’s goods—and even his clothes—in order to place himself naked under the protection of the bishop of Assisi. We can wonder whether this complete reversal might not have been exaggerated later by hagiographers in order to better highlight the contrast between an undoubtedly greedy father—who, after all, was acting in accord with the norms governing family relationships in his society—and a son whose rebellion was about to give birth to a religious movement of great import. Nor should we forget that the vocation of Francis was not at all obvious in the beginning, since he refused to enter into the institutional structures provided by the Church for those who were aspiring to lead a life of perfection outside the world and because he did not envision himself becoming a monk. The Legend of the Three Companions allows us a glimpse of the suffering that Francis experienced when he broke with his family. For the young convert, the family belonged to the world of carnal attachments; but for almost twenty-five years, he had led a life there that was as enjoyable as it was sheltered. To enter into adulthood, even as a religious, bearing a paternal curse, was not an easy undertaking, especially at a time when the individual existed only in relation to his extended family and by virtue of belonging to it. We know from the same source that, in order to erase the cataclysmic consequences of his disownment, “he chose for himself, as a father, a very poor and despised man whom he asked to accompany him, in return for an alms, in order to bless him, by making the sign of the cross over his head, every time that his father, meeting him in the streets of Assisi, repeated his curse.”4 The same legend tells us that, in order to force his son to give him back his money and renounce his portion of the inheritance, Pietro di Bernardone first went to speak to the consuls of the city. However, having learned that Francis was moving toward the religious life, the consuls sent him on to the bishop of Assisi, Guido I (r. 1197–1212), who had jurisdiction over the clerics of his diocese and over those who were aspiring to lead a life consecrated to God.

This detail invites a brief mention of the political and institutional situation of the city in this period. From Lombardy to Latium, throughout the twelfth century, Italy had been marked by the appearance and expansion of the communal regime. Thanks to the struggle that for decades opposed popes to German emperors, numerous Italian cities had acquired a broad administrative autonomy which made them—exceptional in Europe at the time, other than for a few towns in Flanders and in Languedoc—independent centers of power. Detaching themselves from their feudal ties to bishop or count, these urban republics gradually created their own political and judicial institutions. These were in the hands of a ruling group consisting of various vassals of the local prelates, men of law well versed in the knowledge of the law and customs, in addition to a few merchants who had become wealthy in business and through the practice of moneylending. The communes, as they were now known, were ruled by councils comprising elected consuls who controlled power within the city and were its representatives to the outside world.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, there was little harmony in t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- PART I A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH, 1182–1226

- PART II DEATH AND TRANSFIGURATION OF FRANCIS, 1226–1253

- PART III IMAGES AND MYTHS OF FRANCIS OF ASSISI: FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO TODAY

- PART IV THE ORIGINALITY OF FRANCIS AND HIS CHARISM

- Conclusion: Francis, Prophet for His Time … or for Ours?

- Appendix: The Testament of Francis of Assisi, September 1226

- Chronology

- Maps

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index