eBook - ePub

Available until 15 Nov |Learn more

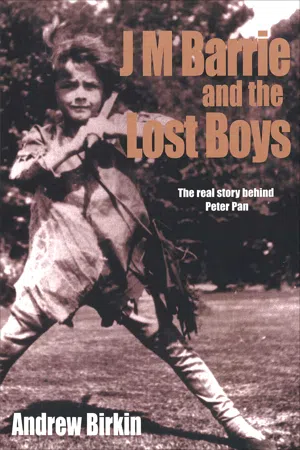

J M Barrie and the Lost Boys

The Real Story Behind Peter Pan

This book is available to read until 15th November, 2025

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 15 Nov |Learn more

About this book

This literary biography is "a story of obsession and the search for pure childhood . . . Moving, charming, a revelation" (

Los Angeles Times).

J. M. Barrie, Victorian novelist, playwright, and author of Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up, led a life almost as interesting as his famous creation. Childless in his marriage, Barrie grew close to the five young boys of the Davies family, ultimately becoming their guardian and surrogate father when they were orphaned.

Andrew Birkin draws extensively on a vast range of material by and about Barrie, including notebooks, memoirs, and hours of recorded interviews with the family and their circle, to describe Barrie's life, the tragedies that shaped him, and the wonderful world of imagination he created for the boys. Updated with a new preface and including photos and illustrations, this "absolutely gripping" read reveals the dramatic story behind one of the classics of children's literature ( Evening Standard).

"A psychological thriller . . . One of the year's most complex and absorbing biographies." — Time

"[A] fascinating story." — The Washington Post

J. M. Barrie, Victorian novelist, playwright, and author of Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up, led a life almost as interesting as his famous creation. Childless in his marriage, Barrie grew close to the five young boys of the Davies family, ultimately becoming their guardian and surrogate father when they were orphaned.

Andrew Birkin draws extensively on a vast range of material by and about Barrie, including notebooks, memoirs, and hours of recorded interviews with the family and their circle, to describe Barrie's life, the tragedies that shaped him, and the wonderful world of imagination he created for the boys. Updated with a new preface and including photos and illustrations, this "absolutely gripping" read reveals the dramatic story behind one of the classics of children's literature ( Evening Standard).

"A psychological thriller . . . One of the year's most complex and absorbing biographies." — Time

"[A] fascinating story." — The Washington Post

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access J M Barrie and the Lost Boys by Andrew Birkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

1860–1885

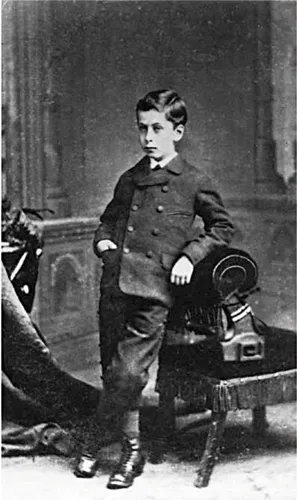

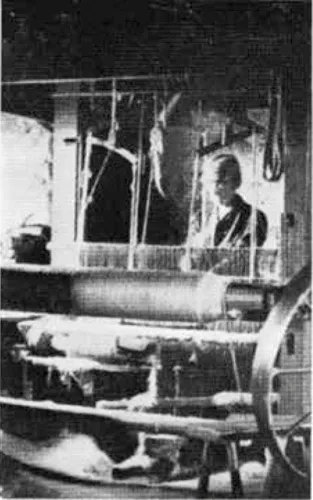

‘On the day I was born we bought six hair-bottomed chairs, and in our little house it was an event’, wrote Barrie in Margaret Ogilvy1 a portrait of his mother and his own boyhood. Certainly his birth caused little stir in a family that already numbered two boys and four girls, but the implied poverty was an affectation adopted by Barrie in later life. His father, David Barrie, was a hand-loom weaver of more than average means, and the dominant priority in the Barrie household was one of fierce educational ambition rather than a struggle for survival. By the time James Barrie was six, that ambition had been partly realized. Alexander Barrie, the eldest son, had graduated from Aberdeen University with first-class honours in Classics, and had opened his own private school in Lanarkshire. The second son, David, was thirteen, and showed every sign of emulating Alexander's achievements; moreover he was tall, athletic, handsome and charming, the Golden Boy of his mother's eye. Margaret Ogilvy (who had retained her maiden name in accordance with an old Scots custom) was the driving force of the family, and all her hopes were focused on the aspiration that David would one day become a Minister. The six-year-old James was, by comparison, something of a disappointment. He showed no particular academic promise, nor did he possess his brother's looks. He was small for his age, rather squat, with a head too large for his body. In short, the runt of the family.

Barrie aged 6

Barrie's birthplace: Lilybank in the Tenements, Kirriemuir. The wash-house in foreground was the theatre of Barrie's first play, written and performed at the age of 7. It was also, according to his Dedication to Peter Pan, ‘the original of the little house the Lost Boys built in the Never Land for Wendy’

Until he was six, James Barrie lived in the shadow of David. But in January 1867, David was killed in a skating accident on the eve of his fourteenth birthday. Barrie was too young to remember the tragedy with any clarity, his chief memory being that of playing with his younger sister Maggie under the table on which stood David's coffin. For his mother, however, it was a catastrophe beyond belief, and one from which she never fully recovered. ‘She was always delicate from that hour, and for many months she was very ill’, wrote Barrie in Margaret Ogilvy. ‘I peeped in many times at the door and then went to the stair and sat on it and sobbed.’ Barrie's elder sister, Jane Ann, was quick to perceive the damaging effect that Margaret Ogilvy's protracted grief was having on her youngest son:

‘This sister told me to go ben to my mother and say to her that she still had another boy. I went ben excitedly, but the room was dark, and when I heard the door shut and no sound come from the bed I was afraid, and I stood still. I suppose I was breathing hard, or perhaps I was crying, for after a time I heard a listless voice that had never been listless before say, “Is that you?” I think the tone hurt me, for I made no answer, and then the voice said more anxiously “Is that you?” again. I thought it was the dead boy she was speaking to, and I said in a little lonely voice, “No, it's no' him, it's just me.” Then I heard a cry, and my mother turned in bed, and though it was dark I knew that she was holding out her arms.

Margaret Ogilvy in 1871

Barrie aged 9

‘After that I sat a great deal in her bed trying to make her forget him. … At first, they say, I was often jealous, stopping her fond memories with the cry, “Do you mind nothing about me?” but that did not last; its place was taken by an intense desire … to become so like him that even my mother should not see the difference, and many and artful were the questions I put to that end. Then I practised in secret, but after a whole week had passed I was still rather like myself. He had such a cheery way of whistling, she had told me, it had always brightened her at her work to hear him whistling, and when he whistled he stood with his legs apart, and his hands in the pockets of his knickerbockers. I decided to trust to this, so one day after I had learned his whistle (every boy of enterprise invents a whistle of his own) from boys who had been his comrades, I secretly put on a suit of his clothes … and thus disguised I slipped, unknown to the others, into my mother's room. Quaking, I doubt not, yet so pleased, I stood still until she saw me, and then—how it must have hurt her! “Listen!” I cried in a glow of triumph, and I stretched my legs wide apart and plunged my hands into the pockets of my knickerbockers, and began to whistle.

‘She lived twenty-nine years after his death … But I had not made her forget the bit of her that was dead; in those nine-and-twenty years he was not removed one day farther from her. Many a time she fell asleep speaking to him, and even while she slept her lips moved and she smiled as if he had come back to her, and when she woke he might vanish so suddenly that she started up bewildered and looked about her, and then said slowly, “My David's dead!” or perhaps he remained long enough to whisper why he must leave her now, and then she lay silent with filmy eyes. When I became a man … he was still a boy of thirteen.’

If Margaret Ogilvy drew a measure of comfort from the notion that David, in dying a boy, would remain a boy for ever, Barrie drew inspiration. It would be another thirty-three years before that inspiration emerged in the shape of Peter Pan, but here was the germ, rooted in his mind and soul from the age of six.

When not acting out the role of his dead brother, Barrie would invent other parts for himself. Some were performed in amateur theatricals in his mother's wash-house; others in real life:

‘When I was a very small boy, another as small was woeful because he could not join in our rough play lest he damaged the “mourning blacks” in which he was attired. So I nobly exchanged clothing with him for an hour, and in mine he disported forgetfully while I sat on a stone in his and lamented with tears, though I knew not for whom.’2 It was this same vicarious curiosity, this ‘devouring desire to try on other folk's feelings as if they were so many suits of clothes’,3 that led the young James Barrie to question his mother about her own girlhood. ‘Those innumerable talks with her made her youth as vivid to me as my own, and so much more quaint, for, to a child, the oddest of things, and the most richly coloured picture-book, is that his mother was once a child also.’ Margaret Ogilvy had a captive audience of one as she unfolded the picture-book of her own childhood: ‘She was eight when her mother's death made her mistress of the house and mother to her little brother, and from that time she scrubbed and mended and baked and sewed, … then [rushed] out in a fit of childishness to play dumps or palaulays with others of her age.’

A hand-loom weaver. The bunches of thread above the loom were known as ‘thrums’, which Barrie later adopted as his pseudonym for Kirriemuir

The story of Margaret Ogilvy's childhood expanded into other stories, told to her as a small girl: tales of the weaving community before the Industrial Revolution, of a Scotland long vanished and coloured by her memory. Many of these stories concerned the Auld Lichts, or Old Lights, a religious sect to which Margaret Ogilvy had belonged before her marriage. These tales, or Idylls, never failed to fire Barrie's imagination, and were, at a later date, to provide him with much of the source material for his articles and ‘Thrums’ novels. But it was the image of the substitute mother that was to take the deepest root: the memory of his own mother as a little girl, refashioned and remoulded into numerous heroines, epitomized as Wendy mothering the Lost Boys and Peter Pan in the Neverland. In Margaret Ogilvy, Barrie admitted with pride that ‘I soon grow tired of writing tales unless I can see a little girl, of whom my mother has told me, wandering confidently through the pages. Such a grip has her memory of her girlhood had upon me since I was a boy of six.’

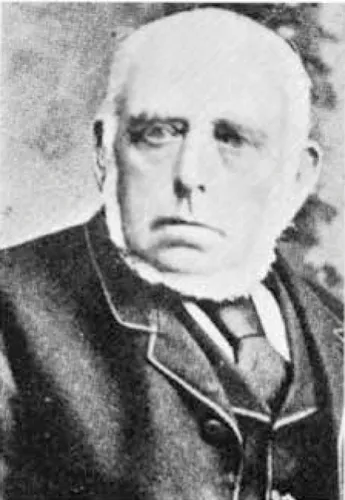

Barrie's father, David Barrie, in about 1871

Barrie's sense of rejection and inferiority, suffered while in the shadow of David, was largely dispelled by his younger sister Maggie. She worshipped him, and her unswerving loyalty and devotion helped to restore in him a measure of self-confidence. Barrie's father, on the other hand, appears to have had little influence on his son's character and development. He is scarcely mentioned in any of Barrie's autobiographical writings, beyond a cursory reference to him in Margaret Ogilvy as ‘a man I am very proud to be able to call my father’, and it was left to his mother to fire the boy with an enthusiasm for literature:

‘We read many books together when I was a boy, “Robinson Crusoe” being the first (and the second), and the “Arabian Nights” should have been the next, for we got it out of the library (a penny for three days), but on discovering that they were nights when we had paid for knights we sent that volume packing, and I have curled my lips at it ever since. … Besides reading every book we could hire or borrow I also bought one now and again, and while buying (it was the occupation of weeks) I read, standing at the counter, most of the other books in the shop, which is perhaps the most exquisite way of reading.’

Barrie also subscribed to various ‘Penny Dreadfuls’—the forerunners of adventure comics—which were, like the later Neverland, ‘not large and sprawly … with tedious distances between one adventure and another, but nicely crammed’.4 In addition to the staple diet of blood and thunder, pirates and desert islands, the penny comics contained serial characters, including a young girl who sold water-cress and bore a striking resemblance to ‘that little girl, of whom my mother has told me’—the young Margaret Ogilvy:

‘This romantic little creature took such hold of my imagination that I cannot eat water-cress even now without emotion. I lay in bed wondering what she would be up to in the next number; I have lost trout because when they nibbled my mind was wandering with her; my early life was embittered by her not arriving regularly on the first of the month. I know not whether it was owing to her loitering on the way one month to an extent flesh and blood could not bear, or because we had exhausted the penny library, but on a day I conceived a glorious idea, or it was put into my head by my mother, then desirous of making progress with her new clouty hearthrug. The notion was nothing short of this, why should I not write the tales myself? I did write them—in the garret—but they by no means helped her to get on with her work, for when I finished a chapter I bounded downstairs to read it to her, and so short were the chapters, so ready was the pen, that I was back with the new manuscript before another clout had been added to the rug. … They were all tales of adventure (happiest is he who writes of adventure), no characters were allowed within if I knew their like in the flesh, the scene lay in unknown parts, desert islands, enchanted gardens, with knights (none of your nights) on black chargers, and round the first corner a lady selling water-cress. … From the day on which I first tasted blood in the garret my mind was made up; there could be no hum-dreadful-drum profession for me; literature was my game.’

Barrie aged 14 at Dumfries Academy

At the age of thirteen, Barrie ‘put the literary calling to bed for a time, having gone to a school where cricket and football were more esteemed’. His childhood was over. In Margaret Ogilvy he wrote:

‘The horror of my boyhood was that I knew a time would come when I also must give up the games, and how it was to be done I saw not (this agony still returns to me in dreams, when...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction to the Yale Edition

- Introduction

- Geneaology

- Prologue

- 1 1860–1885

- 2 1885–1894

- 3 1894–1897

- 4 The Davies Family

- 5 1898–1900

- 6 1900–1901

- 7 1901–1904

- 8 1904–1905

- 9 1905–1906

- 10 1906–1907

- 11 1907–1908

- 12 1908–1910

- 13 1910–1914

- 14 1914–1915

- 15 1915–1917

- 16 1917–1921

- Epilogue

- Sources

- Source notes

- Illustration sources and acknowledgements

- Index