- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

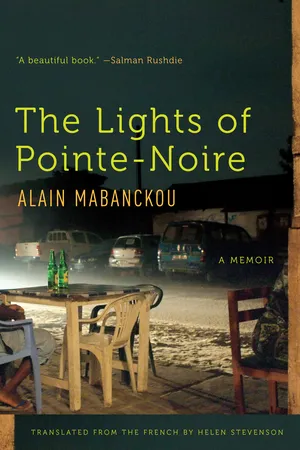

A dazzling meditation on home-coming and belonging from one of “Africa’s greatest writers” and the Man Booker International Prize finalist (The Guardian).

Alain Mabanckou left Congo in 1989, at the age of twenty-two, not to return until a quarter of a century later. When he finally came back to Pointe-Noire, a bustling port town on the Congo’s southwestern coast, he found a country that in some ways had changed beyond recognition: The cinema where, as a child, Mabanckou gorged on glamorous American culture had become a Pentecostal church, and his secondary school has been renamed in honor of a previously despised colonial ruler.

But many things remain unchanged, not least the swirling mythology of Congolese culture that still informs everyday life in Pointe-Noire. Now a decorated writer and an esteemed professor at UCLA, Mabanckou finds he can only look on as an outsider in the place where he grew up. As he delves into his childhood, into the life of his departed mother, and into the strange mix of belonging and absence that informs his return to the Republic of the Congo, his work recalls the writing of V. S. Naipaul and André Aciman, offering a startlingly fresh perspective on the pain of exile, the ghosts of memory, and the paths we take back home.

Grand Prize Winner at the 2015 French Voices Awards

“This is a beautiful book, the past hauntingly reentered, the present truthfully faced, and the translation rises gorgeously to the challenge.” —Salman Rushdie

“A tender, poetic chronicle of an exile’s return.” —Kirkus Reviews

Alain Mabanckou left Congo in 1989, at the age of twenty-two, not to return until a quarter of a century later. When he finally came back to Pointe-Noire, a bustling port town on the Congo’s southwestern coast, he found a country that in some ways had changed beyond recognition: The cinema where, as a child, Mabanckou gorged on glamorous American culture had become a Pentecostal church, and his secondary school has been renamed in honor of a previously despised colonial ruler.

But many things remain unchanged, not least the swirling mythology of Congolese culture that still informs everyday life in Pointe-Noire. Now a decorated writer and an esteemed professor at UCLA, Mabanckou finds he can only look on as an outsider in the place where he grew up. As he delves into his childhood, into the life of his departed mother, and into the strange mix of belonging and absence that informs his return to the Republic of the Congo, his work recalls the writing of V. S. Naipaul and André Aciman, offering a startlingly fresh perspective on the pain of exile, the ghosts of memory, and the paths we take back home.

Grand Prize Winner at the 2015 French Voices Awards

“This is a beautiful book, the past hauntingly reentered, the present truthfully faced, and the translation rises gorgeously to the challenge.” —Salman Rushdie

“A tender, poetic chronicle of an exile’s return.” —Kirkus Reviews

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Lights of Pointe-Noire by Alain Mabanckou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

First week

The miracle woman

For a long time I let people think my mother was still alive. I’m going to make a big effort, now, to set the record straight, to try to distance myself from this lie, which has only served to postpone my mourning. My face still bears the scars of her loss. I’m good at covering them over with a coat of fake good humour, but suddenly they’ll show through, my laughter breaks off and she’s back in my thoughts again, the woman I never saw age, never saw die, who, in my most troubled dreams, turns her back on me, so I won’t see her tears. Wherever I find myself in the world, it takes just the cry of a cat alone at night, or the barking of dogs on heat, and I’ll turn my face to the stars, recalling a tale from my childhood, of the old woman we thought we could see in the moon, carrying a heavy basket on her head. We kids would point her out just with a tilt of the nose, a lift of the chin, convinced we mustn’t point at her or utter the slightest sound, or we’d wake next morning and find we’d been struck deaf or blind, or even with elephantitis or leprosy. We knew, of course, that the miracle woman had no quarrel with children and that the dread diseases she could inflict on peeping toms were punishments reserved for adults who tried to glimpse her naked when she went for a swim up there in the river of clouds. These perverts were encouraged by a handful of charlatans who said that if you saw the old woman without her clothes on it brought blessings on your business and good luck in your everyday life. Now we never really expected things to go all that well, which is probably why we closed our eyes, lying there in the damp grass, so she wouldn’t think we were after the same thing as the grown-ups. She must have had a good laugh to herself up there, reading our innermost thoughts and detecting our every movement, thanks to her perfect ear. She’d turn around, look left, look right, then vanish the second we lay down on our stomachs and pretended to be asleep. We knew she was close by, she was watching us, and maybe she too enjoyed the game, which to us was a bit like hide-and-seek.

Then she’d reappear, we’d see her now, side on, like a shadow puppet, wrapped in layers of dense cloud. We watched her slow progression, transfixed, as a shower of shooting stars fell from her basket, like a firework display to launch the evening drum roll across the land. At that very moment I expect a child was being born somewhere, not knowing it owed its life to this woman, bent double by her penance, but guarantor of all life here below. And at the same time, as a calm fell upon the vault of heaven and at last the moon left the sky, a handful of stars suddenly switched off like lights, as though they’d been hit by bullets from the gun of a hunter standing behind us. We looked at each other, sadly. Someone, somewhere, had died. We knelt down, chin to chest, and mumbled: ‘May his soul rest in peace…’

Who was this nomad of the nights of full moon, whose face no man or woman had ever seen? Some said her story went back to a time when the Earth and the Sky were always squabbling. The Earth said the Sky was faithless and fickle, had mood swings, yelled and roared, while the Sky said the Earth was mindless and dull. God was required to judge between them, and sided with the Sky, since He lived there. And so the miracle woman laid down her life, and took upon herself the sins born of the heedlessness of man. Through this act, she averted a disaster that would have brought about the extermination of the entire human race. During the season before this sacrifice of propitiation, famine and drought on an unprecedented scale came to several villages in the southern Congo. The animals were dying off and so much of the flora vanished that even the most optimistic sorcerers began to predict, within the next quarter-year, the disappearance of the Mayombe forest and the implacable advance of the desert, in which all would perish. That year, bush meat was a distant memory. People ate anything, just to survive, and some villagers made fortunes trading lizards, lightning bugs, ants, beetles, flies and mosquitoes. Within two months these all-invading creatures had completely vanished. There was a rumour that in certain tribes, when someone died, they fought over the body to be sure of at least one whole week of food.

The destruction of our land was foretold by a blind enchantress with a rasping voice and two crippled legs, who shuffled around on her butt. She revealed that the very hands of Time would forget our district, that in the coming days they would stop at midnight, and people would wake on the morning of that terrible moment to a new order of existence: scarcity, or complete absence of water, increased incidence of mirages, sandstorms and deadly heat waves. At first no one took these predictions very seriously. Everyone just said the blind and crippled sorceress was a victim of her own delusions, how else could you explain that each night she’d sell bananas, in front of her property, and though no one ever bought them, they still all disappeared? Where did she find them, when the desert had devoured over half the southern territory? She had more and more customers every day, but where did they all come from? This was in fact the start of the illusions; the sorceress’s wares were the fruit of people’s imagination.

A week after what became known as ‘the Announcement’, the first signs of the end of time began to appear. The birds had gone from the sky, leaving an empty abyss, a sign of a divine anger which even the cleverest sorcerers, powerless in the face of their panoply of limp, unresponsive amulets, could not fathom. These sages came together in a plenary session and took a decision that caused a general uproar: a woman must be ‘handed over’ to appease the divine wrath, and take on her own head the burden of human sin. According to this august assembly, men did not possess this redeeming power, God had only given it to women. The women took this verdict as an insult, and most of the young women shrank from the idea, saying their job was to ensure the line of descent. So that left only the older women. But they said, just because they had reached the twilight of their existence didn’t mean they must accept a sacrifice devised for them by a bunch of old guys using their so-called knowledge of the world of darkness to camouflage their own cowardice. What did they stand to gain, anyway, their lives were nearly over, why should they sacrifice themselves for a happiness they’d never see? While the men and women were arguing it out, the situation got worse. The desert had by now absorbed a good part of the Mayombe forest and was heading off at full pelt towards the country’s heartland. Seeing the country was in a state of breakdown, the miracle woman came down from her cabin perched up on the mountain top, and turned up uninvited in front of the wise men. On the night of a full moon, four sages from the village of Louboulou, and all its sorcerers, dragged her off, far away, into what was still left of the bush. Her hands were tied behind her back with strands of creeper. To some she was a scapegoat, to some a victim who died for the sins of others. They treated her roughly and abused her, which showed how deep was the community’s belief that she had caused all the bad luck that had hit the region. No longer just a willing sacrifice, she was now truly guilty, and had given herself up, and in some people’s eyes that was sufficient, they grabbed their whips, gritted their teeth, and lashed her. Stoically, she stood firm, and walked her Way of the Cross.

In time they came to a waterhole, though it was so small it would probably dry up in a few hours. The moon was full, just brushing the tops of the drought-withered trees. The Eye in the Sky had decided to witness this settling of human scores, so it shed its light upon the scene, until one of the sorcerers, in a quavering voice, began to read out the accusation, decreeing that in the public interest the old woman must live inside the luminous disc from now on and carry a basket on her head till the end of time; unprotesting, the sacrificed woman knelt down in the middle of the waterhole, her hands still bound, and raised her head to the sky. She made not a sound as one of the sorcerers stepped forward with a knife raised above his head. A deathly silence fell, as the sorcerer, with one single, swift and decisive movement, slit the woman’s throat. At once the moon vanished, and did not reappear until the following month, with this time, trapped inside it, an old woman carrying a basket on her head. The southerners were amazed at the sight.

It was decreed that the first Friday of every new year should be the festival of the Sacrifice, when homage would be paid to the old woman. The birds reappeared in our sky, rain fell for a whole week, the harvest brought forth fruit once more, the rivers ran high and teemed with fish, and the animals went forth and multiplied till the bush was crawling with every imaginable species…

I’m grown up now, but belief remains intact, protected by a kind of reverence that resists the lure of Reason. And returning to my roots after twenty-three years away, I feel my faith more than ever. At every full moon anxiety takes hold of me, and pulls me out of doors. Everywhere I see the outline of things, like shadows watching me, surprised to see I’m not paying homage to the miracle woman. And I look up at the sky and I think that maybe the old bohemian has found eternal rest and been replaced by another woman, a bit younger than her, the woman I know best and who would have accepted the sacrifice too, the woman who brought me into the world, Pauline Kengué, who, I will say it, and write it now, to clear up any confusion, died in 1995…

The woman from nowhere

My mother left me with the enduring memory of her light brown eyes. I had to peer down deep into those eyes to catch sight of her worries; she had a way of keeping them from me, through a sudden contraction of her pupils. For her it was a defensive impulse, and for me was one explanation, among others, for why I felt that throughout my childhood she never looked me straight in the eye. I mistrusted her sudden joyful outbursts, which, deep down, concealed her sorrows, and presented me with a distorted image of my mother, as someone well armoured against the frustrations of daily life. I tried to see her more cowardly actions as the sign of inner suffering, but each time I came up against the same mask of serenity she wore every day of her brief existence. It would have been the height of dishonour for her to show me her vulnerability. In almost everything she did, she had one single purpose: to prove to me that with the blessing of our ancestors there was no difficulty on earth she could not overcome, like the time she dreamed that her mother, N’Soko, now deceased, had buried five hundred thousand CFA francs in the sand on the Côte Sauvage, so she went down there at sunrise with her eyes half closed and her hair still wild about her head. There, by chance, she found the stash of money, which made it possible for her to go back into business. Or when she got back from the Grand Marché on a day when things hadn’t gone well, she’d distract me, sending me off to buy a litre of petrol, some spare wicks for the two Luciole storm lamps, then shut herself up in her room, and go back over her accounts. She didn’t notice I was back again, and could hear her still murmuring prayers, blowing her nose and saying my grandmother’s name, over and over, her words interspersed with sobbing. I knew it wasn’t the bad day that had done this to her, it was the presence of the scary straw-hatted scarecrow behind the bedroom door. To me he felt like a human, watching us, moving about. His rags looked like strands of tangled creeper,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- First week

- Last week