eBook - ePub

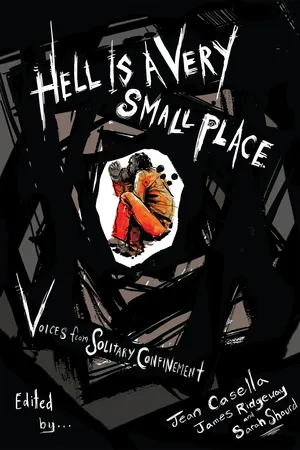

Hell Is a Very Small Place

Voices from Solitary Confinement

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hell Is a Very Small Place

Voices from Solitary Confinement

About this book

“An unforgettable look at the peculiar horrors and humiliations involved in solitary confinement” from the prisoners who have survived it (New York Review of Books).

On any given day, the United States holds more than eighty-thousand people in solitary confinement, a punishment that—beyond fifteen days—has been denounced as a form of cruel and degrading treatment by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Now, in a book that will add a startling new dimension to the debates around human rights and prison reform, former and current prisoners describe the devastating effects of isolation on their minds and bodies, the solidarity expressed between individuals who live side by side for years without ever meeting one another face to face, the ever-present specters of madness and suicide, and the struggle to maintain hope and humanity. As Chelsea Manning wrote from her own solitary confinement cell, “The personal accounts by prisoners are some of the most disturbing that I have ever read.”

These firsthand accounts are supplemented by the writing of noted experts, exploring the psychological, legal, ethical, and political dimensions of solitary confinement.

“Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for twenty-three hours a day, for months, sometimes for years at a time? That is not going to make us safer. That’s not going to make us stronger.” —President Barack Obama

“Elegant but harrowing.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A potent cry of anguish from men and women buried way down in the hole.” —Kirkus Reviews

On any given day, the United States holds more than eighty-thousand people in solitary confinement, a punishment that—beyond fifteen days—has been denounced as a form of cruel and degrading treatment by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Now, in a book that will add a startling new dimension to the debates around human rights and prison reform, former and current prisoners describe the devastating effects of isolation on their minds and bodies, the solidarity expressed between individuals who live side by side for years without ever meeting one another face to face, the ever-present specters of madness and suicide, and the struggle to maintain hope and humanity. As Chelsea Manning wrote from her own solitary confinement cell, “The personal accounts by prisoners are some of the most disturbing that I have ever read.”

These firsthand accounts are supplemented by the writing of noted experts, exploring the psychological, legal, ethical, and political dimensions of solitary confinement.

“Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for twenty-three hours a day, for months, sometimes for years at a time? That is not going to make us safer. That’s not going to make us stronger.” —President Barack Obama

“Elegant but harrowing.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A potent cry of anguish from men and women buried way down in the hole.” —Kirkus Reviews

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hell Is a Very Small Place by Jean Casella, James Ridgeway, Sarah Shourd, Jean Casella,James Ridgeway,Sarah Shourd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Rights. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

VOICES FROM SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

ENDURING

A Sentence Worse than Death

William Blake is in his twenty-ninth year of solitary confinement, currently being served in the Special Housing Unit (SHU) at New York’s Great Meadow Correctional Facility. Born and raised in upstate New York, he spent much of his youth in juvenile jails. In 1987, while in county court on a drug charge, Blake, then twenty-three, grabbed a gun from a sheriff’s deputy and, in a thwarted attempt to escape, murdered one deputy and wounded another. He is now fifty-two years old, and is serving a sentence of seventy-seven years to life. Blake is one of the few people in New York held in “administrative” rather than “disciplinary” segregation—meaning he is considered a permanent risk to prison safety and is in isolation indefinitely, despite periodic pro forma reviews of his status.

The following essay earned Blake an honorable mention in the Yale Law Journal’s Prison Writing Contest. When published on the Solitary Watch website in 2013, the piece went viral worldwide—garnering more than half a million hits on its home site alone as well as being reprinted by numerous other publications and translated into several languages. Blake, who says that reading and writing are what sustain him, began receiving letters from all over the world. In December 2014, Blake was moved from one SHU to another; much of his correspondence was not permitted to follow him, nor were any of the fourteen hundred handwritten pages of the novel he was writing.

“YOU DESERVE AN ETERNITY IN HELL,” ONONDAGA COUNTY SUPREME Court judge Kevin Mulroy told me from his bench as I stood before him for sentencing on July 10, 1987. Apparently he had the idea that God was not the only one qualified to make such judgment calls.

Judge Mulroy wanted to “pump six bucks’ worth of electricity into [my] body,” he also said, although I suspect that it wouldn’t have taken six cents’ worth to get me good and dead. He must have wanted to reduce me and The Chair to a pile of ashes. My “friend” Governor Mario Cuomo wouldn’t allow him to do that, though, the judge went on, bemoaning New York State’s lack of a death statute due to the then-governor’s repeated vetoes of death penalty bills that had been approved by the state legislature. Governor Cuomo’s publicly expressed dudgeon over being called a friend of mine by Judge Mulroy was understandable, given the crimes that I had just been convicted of committing. I didn’t care much for him either, truth be told. He built too many new prisons in my opinion, and cut academic and vocational programs in the prisons already standing.

I know that Judge Mulroy was not nearly alone in wanting to see me executed for the crime I committed when I shot two Onondaga County sheriff’s deputies inside the Town of Dewitt courthouse during a failed escape attempt, killing one and critically wounding the other. There were many people in the Syracuse area who shared his sentiments, to be sure. I read the hateful letters to the editor printed in the local newspapers; I could even feel the anger of the people when I’d go to court, so palpable was it. Even by the standards of my own belief system, such as it was back then, I deserved to die for what I had done. I took the life of a man without just cause, committing an act so monumentally wrong that I could not have argued that it was unfair had I been required to pay with my own life.

What nobody knew or suspected back then, not even I, is that when the prison gate slammed shut behind me, on that very day I would begin suffering a punishment that I am convinced beyond all doubt is far worse than any death sentence could possibly have been. On July 10, 2012, I finished my twenty-fifth consecutive year in solitary confinement, where at the time of this writing I remain. Alhough it is true that I’ve never died and so don’t know exactly what the experience would entail, for the life of me I cannot fathom how dying any death could be harder or more terrible than living through all that I have been forced to endure for the past quarter century.

Prisoners call it the box. Prison authorities have euphemistically dubbed it the Special Housing Unit, or SHU (pronounced “shoe”) for short. In society it is known as solitary confinement. It is twenty-three-hour-a-day lockdown in a cell smaller than some closets I’ve seen, with one hour allotted to “recreation” consisting of placement by oneself in a concrete-enclosed yard or, in some prisons, a cage made of steel bars. There is nothing in a SHU yard but air: no TV, no balls to bounce, no games to play, no other inmates, nothing. There is also very little allowed in a SHU cell: three sets of plain white underwear, one pair of green pants, one green short-sleeved button-up shirt, one green sweatshirt, one pair of laceless footwear that I’ll call sneakers for lack of a better word, ten books or magazines total, twenty pictures of the people you love, writing supplies, a bar of soap, toothbrush and toothpaste, one deodorant stick, but no shampoo.

That’s about it. No clothes of your own, only prison-made. No food from commissary or packages, only three unappetizing meals a day handed to you through a narrow slot in your cell door. No phone calls, no TV, no luxury items at all. You get a set of cheap headphones to use, and you can pick between the two or three (depending on which prison you’re in) jacks in the cell wall to plug into. You can listen to a TV station in one jack, and use your imagination while trying to figure out what is going on when the music indicates drama but the dialogue doesn’t suffice to tell you anything. Or you can listen to some music, but you’re out of luck if you’re a rock ’n’ roll fan and find only rap is playing.

Your options as to what to do to occupy your time in SHU are scant, but there will be boredom aplenty. You probably think that you understand boredom, know its feel, but really you don’t. What you call boredom would seem a whirlwind of activity to me, choices so many that I’d likely be befuddled in trying to pick one over all the others. You could turn on a TV and watch a movie or some other show; I haven’t seen a TV since the 1980s. You could go for a walk in the neighborhood; I can’t walk more than a few feet in any direction before I run into a concrete wall or steel bars. You could pick up your phone and call a friend; I don’t know if I’d be able to remember how to make a collect call or even if the process is still the same, so many years it’s been since I’ve used a telephone. Play with your dog or cat and experience their love, or watch your fish in their aquarium; the only creatures I see daily are the mice and cockroaches that infest the unit, and they’re not very lovable and nothing much to look at. There is a pretty good list of options available to you, if you think about it, many things that you could do even when you believe you are so bored. You take them for granted because they are there all the time, but if it were all taken away you’d find yourself missing even the things that right now seem so small and insignificant. Even the smallest stuff can become as large as life when you have had nearly nothing for far too long.

I haven’t been outside in one of the SHU yards in this prison for about four years now. I haven’t seen a tree or blade of grass in all that time, and wouldn’t see these things were I to go to the yard. In Elmira Correctional Facility, where I am presently imprisoned, the SHU yards are about three or four times as big as my cell. There are twelve SHU yards total, each surrounded by concrete walls, one or two of the walls lined with windows. If you look in the windows you’ll see the same SHU cellblock that you live on, and maybe you’ll get to see the guy who has been locked next to you for months that you’ve talked to every day but had never before gotten a look at. If you look up you’ll find bars and a screen covering the yard, and if you’re lucky maybe you can see a bit of blue sky through the mesh, otherwise it’ll be hard to believe that you’re even outside. If it’s a good day you can walk around the SHU yard in small circles staring ahead with your mind on nothingness, like the nothing you’ve got in that little lacuna with you. If it’s a bad day, though, maybe your mind will be filled with remembrances of all you used to have that you haven’t seen now for many years; and you’ll be missing it, feeling the loss, feeling it bad.

Life in the box is about an austere sameness that makes it difficult to tell one day from a thousand others. Nothing much and nothing new ever happens to tell you if it’s a Monday or a Friday, March or September, 1987 or 2012. The world turns, technology advances, and things in the streets change and keep changing all the time. Not so in a solitary confinement unit, however. I’ve never seen a cell phone except in pictures in magazines. I’ve never touched a computer in my life, never been on the Internet and wouldn’t know how to get there if you sat me in front of a computer, turned it on for me, and gave me directions. SHU is a timeless place, and I can honestly say that there is not a single thing I’d see looking around right now that is different from what I saw in Shawangunk Correctional Facility’s box when I first arrived there from Syracuse’s county jail in 1987. Indeed, there is probably nothing different in SHU now than in SHU a hundred years ago, save the headphones. Then and now there were a few books, a few prison-made clothing articles, walls and bars and human beings locked in cages. And misery.

There is always the misery. If you manage to escape it yourself for a time, there will ever be plenty around in others for you to sense; and although you’ll be unable to look into their eyes and see it, you might hear it in the nighttime when tough guys cry not-so-tough tears that are forced out of them by the unrelenting stress and strain that life in SHU is an exercise in.

I’ve read of the studies done regarding the effects of long-term isolation in solitary confinement on inmates, seen how researchers say it can ruin a man’s mind, and I’ve watched with my own eyes the slow descent of sane men into madness—sometimes not so slow. What I’ve never seen the experts write about, though, is what year after year of abject isolation can do to that immaterial part in our middle where hopes survive or die and the spirit resides. So please allow me to speak to you of what I’ve seen and felt during some of the harder times of my twenty-five-year SHU odyssey.

I’ve experienced times so difficult and felt boredom and loneliness to such a degree that it seemed to be a physical thing inside so thick it felt like it was choking me, trying to squeeze the sanity from my mind, the spirit from my soul, and the life from my body. I’ve seen and felt hope becoming like a foggy ephemeral thing, hard to get ahold of, even harder to keep ahold of as the years and then decades disappeared while I stayed stuck in the emptiness of the SHU world. I’ve seen minds slipping down the slope of sanity, descending into insanity, and I’ve been terrified that I would end up like the guys around me who have cracked and become nuts. It’s a sad thing to watch a human being go insane before your eyes because he can’t handle the pressure that the box exerts on the mind, but it is sadder still to see the spirit shaken from a soul. And it is more disastrous. Sometimes the prison guards find them hanging and blue; sometimes their necks get broken when they jump from their beds, the sheet tied around the neck that’s also wrapped around the grate covering the light in the ceiling snapping taut with a pop. I’ve seen the spirit leaving men in SHU, and I have witnessed the results.

The box is a place like no other place on planet Earth. It’s a place where men full of rage can stand at their cell gates fulminating on their neighbor or neighbors, yelling and screaming and speaking some of the filthiest words that could ever come from a human mouth, do it for hours on end, and despite it all never suffer the loss of a single tooth, never get their heads knocked clean off their shoulders. You will never hear words more despicable or see mouth wars more insane than what occurs all the time in SHU, not anywhere else in the world, because there would be serious violence before any person could speak so much foulness for so long. In the box the heavy steel bars allow mouths to run with impunity when they could not otherwise do so, while the ambiance is one that is sorely conducive to an exceedingly hot sort of anger that seems to press the lips on to ridiculous extremes. Day and night I have been awakened by the sound of rage being loosed loudly on SHU gates, and I’d be a liar if I said that I haven’t at times been one of the madmen doing the yelling.

I have lived for months where the first thing I became aware of upon waking in the morning is the malodorous funk of human feces, tinged with the acrid stench of days-old urine, where I ate my breakfast, lunch, and dinner with that same stink assaulting my senses, and where the last thought I had before falling into unconscious sleep was: “Damn, it smells like shit in here.” I have felt like I was on an island surrounded by vicious sharks, flanked on both sides by mentally ill inmates who would splash their excrement all over their cells, all over the company outside their cells, and even all over themselves. I have seen days turn into weeks that seemed like they’d never end without being able to sleep more than short snatches before I was shocked out of my dreams, and thrown back into a living nightmare, by the screams of sick men who had lost all ability to control themselves, or by the banging of the cell bars and walls being done by these same madmen. I have been so tired when sleep inside was impossible that I went outside into a snowstorm to get some rest.

The wind blew hard and snowflakes swirled around and around in the small SHU yard at Shawangunk, and I had on but one cheap prison-produced coat and a single set of state clothes beneath. To escape the biting cold I dug into the seven- or eight-foot-high mountain of snow that was piled in the center of the yard, the accumulation from inmates shoveling a narrow path to walk along the perimeter. With bare hands gone numb, I dug out a small room in that pile of snow, making myself a sort of igloo. When it was done I crawled inside, rolled onto my back on the snow-covered concrete ground, and almost instantly fell asleep, my bare head pillowed in the snow. I didn’t even have a hat to wear.

An hour or so later I was awakened by the guards come to take me back to the stink and insanity inside: “Blake, rec’s over. . . .” I had gotten an hour’s straight sleep, minus the few minutes it had taken me to dig my igloo. That was more than I had gotten in weeks without being shocked awake by the CA-RACK! of a sneaker being slapped into a Plexiglas shield covering the cell of an inmate who had thrown things nasty; or the THUD-THUD-THUD! of an inmate pounding his cell wall; or bars being banged and gates being kicked and rattled; or men screaming like they’re dying and maybe wishing that they were; or to the tirade of an inmate letting loose his pent-up rage on a guard or fellow inmate, sounding every bit the lunatic that too long a time in the mind-breaking confines of the box had caused him to be.

I have been so exhausted physically, my mental strength tested to limits that can cause strong folks to snap, that I have begged God, tough guy I fancy myself, “Please, Lord, make them stop. Please let me get s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: “A Human Forever”

- Introduction

- Part I: Voices from Solitary Confinement

- Part II: Perspectives on Solitary Confinement

- Afterword: “Exposing Torture”

- Acknowledgments

- About the Editors

- About Solitary Watch