- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A historian examines why Hungary allied with the Nazis, and the devastating consequences for the country.

The full story of Hungary's participation in World War II is part of a fascinating tale of rise and fall, of hopes dashed and dreams in tatters. Using previously untapped sources and interviews she conducted for this book, Deborah S. Cornelius provides a clear account of Hungary's attempt to regain the glory of the Hungarian Kingdom by joining forces with Nazi Germany—a decision that today seems doomed to fail from the start. For scholars and history buffs alike, Hungary in World War II is a riveting read.

After the First World War, the new country of Hungary lost more than 70 percent of its territory and saw its population reduced by nearly the same percentage. But in the early years of World War II, Hungary enjoyed boom times—and the dream of restoring the Hungarian Kingdom began to rise again.

As the war engulfed Europe, Hungary was drawn into an alliance with Nazi Germany. When the Germans appeared to give Hungary much of its pre-World War I territory, Hungarians began to delude themselves into believing they had won their long-sought objective. Instead, the final year of the world war brought widespread destruction and a genocidal war against Hungarian Jews. Caught between two warring behemoths, the country became a battleground for German and Soviet forces—and in the wake of the war, Hungary suffered further devastation under Soviet occupation and forty-five years of communist rule. This is the story of a tumultuous time and a little-known chapter in the sweeping history of World War II.

The full story of Hungary's participation in World War II is part of a fascinating tale of rise and fall, of hopes dashed and dreams in tatters. Using previously untapped sources and interviews she conducted for this book, Deborah S. Cornelius provides a clear account of Hungary's attempt to regain the glory of the Hungarian Kingdom by joining forces with Nazi Germany—a decision that today seems doomed to fail from the start. For scholars and history buffs alike, Hungary in World War II is a riveting read.

After the First World War, the new country of Hungary lost more than 70 percent of its territory and saw its population reduced by nearly the same percentage. But in the early years of World War II, Hungary enjoyed boom times—and the dream of restoring the Hungarian Kingdom began to rise again.

As the war engulfed Europe, Hungary was drawn into an alliance with Nazi Germany. When the Germans appeared to give Hungary much of its pre-World War I territory, Hungarians began to delude themselves into believing they had won their long-sought objective. Instead, the final year of the world war brought widespread destruction and a genocidal war against Hungarian Jews. Caught between two warring behemoths, the country became a battleground for German and Soviet forces—and in the wake of the war, Hungary suffered further devastation under Soviet occupation and forty-five years of communist rule. This is the story of a tumultuous time and a little-known chapter in the sweeping history of World War II.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hungary in World War II by Deborah S. Cornelius in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Legacy of World War I

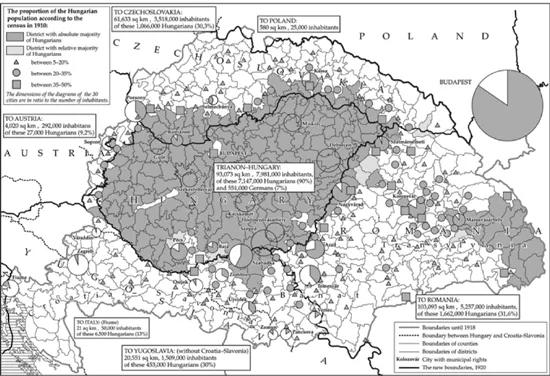

To understand Hungary’s role in World War II, one must go back to World War I and the defeat of the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria) by the Triple Entente (Great Britain, France, and Russia), the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and the tumultuous years between 1918 and 1920. During this brief period, the thousand-year-old Kingdom of Hungary disintegrated, the Habsburg monarch, Charles I, abdicated in favor of a republic, Hungary’s neighbors occupied much of the country, and a short-lived Bolshevik regime took control. As a final blow to the devastated and demoralized Hungarian people, the peace treaty signed at the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles confirmed the loss of two-thirds of Hungary’s territory and three-fifths of its people, reducing the population from 18.2 million to 7.9 million. Hungarians felt a deep sense of injustice at the dismemberment of their kingdom and believed that the Treaty of Trianon had been a dreadful mistake that would eventually be rectified.

Once a part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the largest state in Europe, Hungary had become a small country in Central Europe, cut off from the sea and the outside world, and surrounded by antagonistic neighbor states. The territories lost had been integral parts of the Kingdom of Hungary and carried great symbolic value. Transylvania, ceded to Romania, had been considered the Hungarian homeland from the time of the entrance of the first Magyar tribes. Northern Hungary, ceded to Czechoslovakia, was the only part of the kingdom that had maintained Hungary’s independence during the Turkish occupation. Its main city, Pozsony/Bratislava, had been the site of the Hungarian parliament until 1848 and the crowning of Hungarian kings (see Map 2).

The losses were so drastic that Hungarians struggled to understand the reasons for this catastrophe. Although many of those who lived in the territories lost to the neighbor states were non-Magyar—not ethnic Hungarians—over three million considered themselves Magyar.1 One and one-half million of these lived in solidly Hungarian-inhabited belts near the new borders. Even though the treaty in principle had been based on self-determination, the areas populated by a majority of Hungarian speakers were granted to the neighbor states without plebiscites.2 Viewed by Hungarian citizens as a grave injustice, the cutting off of the Hungarian-inhabited territories blinded the population to the claims of non-Hungarians for self-determination. The result was a complete denial of the peace treaty and widespread demands for mindent vissza (everything back), an attitude that was to persist throughout World War II.

Map 2. Trianon-Hungary, after the Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920.

During the final weeks of World War I the Habsburg Monarchy began to disintegrate. On October 28, 1918, the Czechs seceded from the Austrian Empire, announcing the formation of an independent Czechoslovak Republic. Two days later, a Slovak national council proclaimed their independence from the Hungarian Kingdom and union with the Czech state. In Zagreb, on October 29, the Croatian National Council of Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes declared their independence from Austria-Hungary. Romanians living in Transylvania proclaimed their secession on October 27, although they did not give up the idea of autonomy until December, and Ukrainians (Ruthenians) announced secession on October 31. On October 30 the Austrian National Assembly adopted a provisional constitution, and finally, on October 31, a democratic revolution broke out in Hungary. By the time an armistice was signed on November 3, 1918, the monarchy had ceased to exist.

The Hungarian Revolutions of 1918 and 1919

In the fall of 1918, as it became clear that the war had been lost, revolutionary forces began gathering in Budapest. Tensions among the population had been rising, with food riots, strikes, and increasing desertions from the army—a result of the terrible losses during the war, rising prices and growing shortages. The revolutionary spirit of the October Revolution of 1917 was spreading, fueled by the returning Hungarian prisoners of war from Russia with demonstrations expressing sympathy with the Bolsheviks and demanding peace. On the evening of October 30 news came of a revolution in Vienna and the crowds grew larger. The revolution began with the troops, which had been brought to Budapest in order to crush the popular movement. Officers and soldiers tore the imperial ensigns from their caps and replaced the emblem with the red and white aster flowers on sale to celebrate All Souls’ Day, launching the so-called Aster Revolution.

Count Mihály Károlyi, a pacifist and idealist, emerged as the symbol of the revolution. Despite his aristocratic heritage he had become the most popular politician in Hungary. During worker strikes in June 1918, which were put down brutally by the military, the party led by Károlyi took on the role of speaking for the striking workers in Parliament.3 The revolutionaries united around him as head of the recently formed revolutionary National Council, and he became prime minister in November 1918. The Social Democrats, who had never been represented in Parliament, became the main support of the government because of their popular appeal, along with an efficient centralized machinery and affiliation with labor unions.4 People were tired of war and wanted reforms. Colonel Linder, minister of war, in a move that soon proved to be a mistake, dismissed the army on November 2 with the slogan, “I never want to see a soldier again.”5

In the early weeks of his ministry, Károlyi enjoyed countrywide popularity. The revolution was accomplished with little bloodshed, accompanied by great optimism that order would be restored and peace made with the Entente powers, especially since it was known that Károlyi had good relations with the principal members of the Entente. During the war he had made covert contacts with British and French diplomats in Switzerland and proclaimed himself a follower of Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Many welcomed Károlyi’s liberal reform program, designed to deal with the political issues that the former conservative government had failed to address. Károlyi, one of the richest landowners in Hungary, aimed to liquidate the semi-feudal remnants of an outmoded order, and promised land reform, autonomy to the national minorities, and universal suffrage including women. Liberals, the younger clergy and the members of the feminist movement enthusiastically supported his plans for reform.6 Károlyi was confirmed by the Habsburg Emperor and King of Hungary, Charles IV, who abdicated on November 13, and on November 16 the National Council announced the People’s Republic of Hungary before Parliament. Hungary had finally regained its independence, but as a defeated nation.7

The surrender of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy on November 3 in the Padua Armistice had virtually ignored Hungary. Károlyi, alarmed at the imminent invasion of Hungary from the south by the Serbs and French, decided to send a delegation to Belgrade to discuss the application of the Padua armistice agreement to Hungary. On November 7 Károlyi led the delegation to negotiate with French General Louis Franchet d’Esperey, Allied Commander of the Balkan armies in Belgrade. The delegation was full of optimism, believing that the establishment of a democratic republic would meet Wilson’s conditions for peace. In an effort to indicate the democratic nature of the new Hungary, the delegation included a Social Democrat as well as a representative of the Soldiers’ and Workers’ councils. Their expectations were disappointed. The Entente powers were suspicious of the liberal revolution, and the French particularly were concerned for their own security. They greatly feared the spread of the Russian Revolution to Central and Western Europe, and the Hungarian Soldiers’ and Workers’ councils appeared much too similar to those established in Russia by the Bolsheviks.

General d’Esperey dashed their hopes, greeting them coldly and speaking as conqueror to the conquered. One of the participants noted that General d’Esperey “identified himself more with the despised Austro-Hungarian generals than with the democratic military organization that was responsible for the revolution among the belligerents.”8 When Károlyi asked for fair treatment of his government as the true representative of the Hungarian people, d’Esperey interrupted him saying that he was only a representative of the Magyars. “I know your history,” he said. “In your country you have oppressed those who are not Magyar. Now you have the Czechs, Slovaks, Rumanians, Yugoslavs as enemies; I hold these people in the hollow of my hand. I have only to make a sign and you will be destroyed.”9

General d’Esperey was rude to the representative of the National Council, Jewish Baron Lajos Hatvany, humiliating him, and sarcastic to the soldier-worker representative who appeared in a revolutionary uniform which he had designed himself. D’Esperey exclaimed: “Vous êtes tombés si bas!” (You have fallen so low!) He said that he had agreed to talk with them only out of respect for Károlyi and urged them to support Károlyi as Hungary’s only hope. His cold tone softened only when he asked about the “unfortunate young king.”10 Károlyi tactfully avoided explaining that the government was about to dethrone King Charles and declare a people’s republic. But despite d’Esperey’s hectoring and insults, the Hungarians were offered reasonably fair terms at the time.

Károlyi continued his attempt to establish diplomatic relations with the victors, but without success. He hoped to gain the support of President Wilson whose Fourteen Points speech had been greeted enthusiastically by the Hungarian population, but Wilson as well as the British had adopted a wait-and-see attitude, leaving military decisions in the area to the French. The Allies had decided that Hungary, like Germany, was to be treated as an enemy state. In their fear of revolution and Bolshevism, they gave way to the French policy, which was intended to create a chain of strong successor states—Czecho-Slovakia, Romania, and the South Slav states—as a protective belt against Germany and Soviet Russia. The protective belt was to cover as much of the territory of the former monarchy as possible, regardless of ethnic considerations.11

The liberal revolution, rather than gaining their favor, only increased their fears of the spread of Bolshevism. They suspected that the Károlyi government was a possible carrier of Bolshevism and refused to recognize the new government. During the next months, the government’s primary concern—along with the attempt to establish diplomatic relations with the Entente powers—was to hold the country together.

In November 1918, Oszkár Jászi, head of the new ministry for nationality affairs, began to negotiate with leaders of the non-Hungarian nationalities. A proponent of a federal solution to the question of nationalities within the monarchy, Jászi offered the non-Hungarian nationalities maximum autonomy within the borders of Hungary, but these offers came much too late. For a time, negotiations with the Slovak representative, Milan Hodža, appeared to be positive, but Hodža was abruptly withdrawn by the new Czech government; autonomy for the Slovaks would destroy their plans for a Czecho-Slovak state. Only the Ruthenians, the Ukrainian population of Hungary, agreed to the terms. The Transylvanian Romanians at first had aimed for autonomy, fearing that Transylvania would be swallowed up by the more backward and conservative Romanian Old Kingdom, but in December they voted to join Greater Romania.12

The military convention signed on November 13 had established a demarcation line between Hungary and those territories that had seceded from the Monarchy. However, the new Czecho-Slovak republic, Romania, and the South Slav states, eager to be in possession of the lands they claimed by the time the peace conference began, ignored the agreement. The refusal by the Entente to prevent Hungary’s neighbors from occupying Hungarian territory before the conclusion of the peace treaty came in direct violation of the Belgrade military convention.13 Hungary’s neighbors were encouraged by the French who aimed to strengthen these countries against Bolshevik Russia. France’s earlier concern to build a united defense against Germany had changed after the Bolshevik revolution and the defeat of the Central powers. Now the planned barrier of East European countries against Germany was to be anti-Russian. The Czech Legion, which had been organized in Russia and involved in fighting the Reds in Siberia, had been under nominal French command since December 1917. Poland and Romania both had territorial claims against Communist Russia.14

Supported by the French, Serbian, and Romanian troops occupied southern Hungary, Czech troops began to invade northern Hungary, and Romanian troops moved west to take Transylvania. The Entente powers ordered Hungarian troops to evacuate Slovakia and the Romanian army entered Kolozsvár, the capital of Transylvania. By January, Hungary had lost more than half of its former territory. Authorized by the Entente, the neighbor countries sent in troops as well as civil authorities to the Hungarian territories that they claimed. The territory they occupied corresponded roughly to what was to become the new Hungarian frontier.

The occupation came as a tremendous shock to the Hungarian inhabitants; it was incomprehensible to them that they should be under a foreign rule. Rezső Peery, then a small boy of nine, recalled his amazement when Czech troops occupied his city in northern Hungary: “I gaped in astonishment at … the long long procession of armed troops marching toward the Market square.”15 Italian Alpine troops accompanied the Czech forces invading Pozsony/Bratislava. “The occupation of the city in 1919 was accompanied by such brutality that it aroused the spirit of opposition in even the most tolerant.... The barbarities of the occupation remained before our eyes… . Respect for the interests of honor, truth, spirit and culture, were thus interwoven in our eyes with the matter of national loyalty. As it was said in the case of Alsace-Lorraine: ‘Jamais en parler, toujours y penser’ [Never talk about it, always think about it]—that was our attitude in national matters, just like the Alsacians.”16

Erzsébet Arvay told of the bitter night in 1918 when her family debated whether to leave their village in Transylvania where her father was the teacher: “My father paced the room during the whole night trying to decide whether we should flee or stay.” The family traveled in chaotic conditions by train with seven-year-old Erzsébet and her two-week-old baby sister to the home of her mother’s parents in Transdanubia.17

In this difficult situation, the Károlyi government’s position became more and more tenuous as the population lost faith in its ability to deal with the Entente. On November 24, led by Béla Kun, revolutionary soldiers who had returned from Soviet prisoner of war camps established the Communist Party of Hungary, and the peacemakers became more and more convinced hat Hungary was rapidly becoming a hotbed of Bolshevism and anarchy.18

In mid-December the British war cabinet debated the Hungarian government’s request to send a mission to Paris, and agreed with the French that Hungary as a defeated country had no right to send a mission. In addition to the breakdown of civil administration, the collapse of the transport system, and inflation, the economic blockade by the Entente prevented the entry of food and coal. The coal blockade by the Czech government caused economic havoc in Hungary. The mayor of Budapest appealed to President Wilson to have the Czechs lift the blockade, but Beneš frankly admitted that the Czechs expected to exploit the coal situation to hold Hungary in check.19 Since Hungary had signed an armistice and not a peace treaty the Allied blockade continued. People cut down their trees for heat; trains cut their schedules, and city lighting was reduced.

Enthusiasm for the regime was fading. Károlyi began to implement his reform program, but progress was slow. With the increase of discontent the number of social democrats in the government was increased. Aristocrats, who had always been suspiciou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Legacy of World War I

- 2 Hungary Between the Wars

- 3 The Last Year of European Peace

- 4 Clinging to Neutrality

- 5 Hungary Enters the War

- 6 Disaster at the Don

- 7 Efforts to Exit the War

- 8 German Occupation

- 9 From Arrow Cross Rule to Soviet Occupation

- 10 Postwar Hungary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index