eBook - ePub

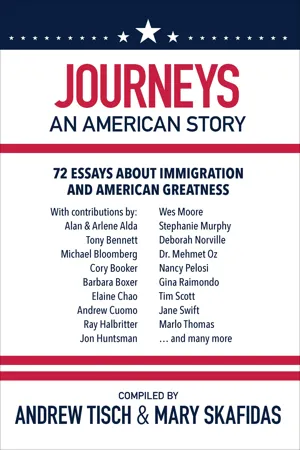

Journeys: An American Story

72 Essays about Immigration and American Greatness

- 345 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Journeys: An American Story

72 Essays about Immigration and American Greatness

About this book

A compilation of American immigration tales, featuring seventy-two essays from Nancy Pelosi, Dr. Oz, Michael Bloomberg, Alan Alda, Mary Choi, and others.

Journeys captures the quintessential idea of the American dream. The individuals in this book are only a part of the brilliant mosaic of people who came to this country and made it what it is today. Read about the governor's grandfathers who dug ditches and cleaned sewers, laying the groundwork for a budding nation; how a future cabinet secretary crossed the ocean at age eleven on a cargo ship; about a young boy who fled violence in Budapest to become one of the most celebrated American football players; the girl who escaped persecution to become the first Vietnamese American woman ever elected to the US congress; or the limo driver whose family took a seventy-year detour before finally arriving at their original destination, along with many other fascinating tales of extraordinary and everyday Americans.

In association with the New-York Historical Society, Andrew Tisch and Mary Skafidas have reached out to a variety of notable figures to contribute an enlightening and unique account of their family's immigration story. All profits will be donated to the New-York Historical Society and the Statue of Liberty Ellis Island Foundation.

Featuring essays by: Arlene Alda, Tony Bennett, Cory Booker, Barbara Boxer, Elaine Chao, Andrew Cuomo, Ray Halbritter, Jon Huntsman, Wes Moore, Stephanie Murphy, Deborah Norville, Dr. Mehmet Oz, Gina Raimondo, Tim Scott, Jane Swift, Marlo Thomas, And many more!

"Illustrate[s] the positive and powerful impact that immigration has had in weaving the fabric of America . . . inspiring." —Warren Buffett

Journeys captures the quintessential idea of the American dream. The individuals in this book are only a part of the brilliant mosaic of people who came to this country and made it what it is today. Read about the governor's grandfathers who dug ditches and cleaned sewers, laying the groundwork for a budding nation; how a future cabinet secretary crossed the ocean at age eleven on a cargo ship; about a young boy who fled violence in Budapest to become one of the most celebrated American football players; the girl who escaped persecution to become the first Vietnamese American woman ever elected to the US congress; or the limo driver whose family took a seventy-year detour before finally arriving at their original destination, along with many other fascinating tales of extraordinary and everyday Americans.

In association with the New-York Historical Society, Andrew Tisch and Mary Skafidas have reached out to a variety of notable figures to contribute an enlightening and unique account of their family's immigration story. All profits will be donated to the New-York Historical Society and the Statue of Liberty Ellis Island Foundation.

Featuring essays by: Arlene Alda, Tony Bennett, Cory Booker, Barbara Boxer, Elaine Chao, Andrew Cuomo, Ray Halbritter, Jon Huntsman, Wes Moore, Stephanie Murphy, Deborah Norville, Dr. Mehmet Oz, Gina Raimondo, Tim Scott, Jane Swift, Marlo Thomas, And many more!

"Illustrate[s] the positive and powerful impact that immigration has had in weaving the fabric of America . . . inspiring." —Warren Buffett

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Journeys: An American Story by Andrew Tisch, Mary Skafidas, Andrew Tisch,Mary Skafidas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Theory & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Strivers

Michael Bloomberg

Joseph Bower

Andrew Cuomo

Ben Freeman

Peter Blair Henry

Declan Kelly

Jackie Koppell

Funa Maduka and Nonso Maduka

Mario Neiman

Tim Scott

Mary Skafidas

Jane Wang

Michael R. Bloomberg

Michael R. Bloomberg is an entrepreneur and philanthropist who served as Mayor of New York City for three terms. Since leaving city hall in 2014, he has resumed leadership of Bloomberg LP and become a UN Special Envoy for Climate Action, and the World Health Organization’s Global Ambassador for Noncommunicable Diseases.

One reason I ran for mayor of New York was to improve the city’s failing public school system. When I visited classrooms, I saw bright, eager students—many of them immigrants and children of immigrants—whose ambitions and aspirations personified the American dream. Yet for too long, the city’s public schools did not give them the tools and skills they needed to fulfill their potential. I was determined to change that, and my own family’s history gave me a sense of just how important the work was.*

Three of my grandparents and six of my great-grandparents were immigrants. All placed education and reverence for the United States at the core of our family values. Their stories are quintessentially American, and they made my story possible.

My maternal grandparents were Ettie and Max Rubens. Ettie was born on Mott Street in 1881. She grew up on the Lower East Side, a haven for immigrants. Ettie’s parents, Louis and Ida Cohen, had come from the Kovno region of present-day Lithuania. Louis Cohen arrived in New York City in 1869. He was so proud to become an American citizen that he hung his naturalization certificate on the wall. Great-Grandmother Ida lived in New York City until she died in 1917 at 64 East 105th Street, between Madison and Park in East Harlem, a house her son Henry owned. Her death notice listed her membership in more than a dozen Jewish and community organizations.

Ettie was educated in a Lower East Side public school, where students wrote on slates because paper was too precious. I don’t know the school’s name or how long she attended; I do know that throughout her life she was a voracious reader, and she completed the daily and Sunday New York Times crossword puzzles until she was ninety!

In 1903, she married my grandfather, Max Rubens, for whom my sister and I are named. They went to Washington, DC, on their honeymoon and brought back a souvenir that we still have—a plaque of the Capitol made from old currency that had been destroyed by the United States Mint. It’s a touching reminder of the stock that immigrant families placed in American institutions.

Grandpa Max arrived in America as a child. He and his parents, Grace and Cappell, had quite a pathway to America. From a small town near Grodno in present-day Belarus, they made their way to Liverpool, where they settled for several years. A photo of 6 Mela Street, where they lived in the 1880s, is as bleak as a Dickens story. My sister even found records showing that Max and his brother Charlie received clothes from a charity “for the poor boys of the Liverpool Hebrew School.” (Their sister Polly, as a girl, did not qualify, though she attended the same school.) They left for America in 1886 on the ship City of Hope and settled in Salem, Massachusetts. A few years later, they went back to Liverpool, but left for good in 1891, settling in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Max earned his living in the wholesale grocery business, carrying around heavy grocery samples in a Gladstone bag. He was able to buy a row of five brick three-family houses on Summit Avenue in West Hoboken, a German neighborhood where our mother spent her childhood. From my mother, we know that Max was a great music lover and had a very good ear. At about age twenty, he learned to play the violin. Grandma Ettie also loved music; she played the piano, and they often played duets. They listened to classical records on their Victrola, a lot of opera, especially Caruso, Max’s favorite, and they went into New York City for live opera and theater.

Grandma Ettie passed on high expectations for learning to all her children, whom she raised alone after Max died in 1922. It was expected that my then sixteen-year-old uncle Louis would leave school after Max’s death to go to work, but Ettie insisted that he finish high school before joining Hudson Wholesale Grocery, where he thrived for the rest of his life. My mother, Charlotte, graduated from Dickinson High School in 1925 and from New York University in 1929, in an era when relatively few women attended college. Grandma encouraged Aunt Florrie to train as a teacher and my aunt Gertie to attend a business secretarial school.

Grandma Ettie’s emphasis on education helped make her successful as a mother. The city’s public schools shaped her and reinforced her sense of what her children and grandchildren could achieve. My mother held her parents up as models of what America offered “if you applied yourself”—with the key word being if.

My father, Bill Bloomberg, was born just outside Boston, in Chelsea, in 1906, to parents who both came from Vilna, Lithuania. His mother, Rose Bernstein, arrived in 1891 as a twelve-year-old with her mother and four siblings; four more were born in America. Rose’s father, Gedalia, had arrived two years earlier, following some of his own siblings who braved the way. Some of them are listed in an 1881 Boston city directory as living on Nashua Street, not far from the current Museum of Science, an institution that gave me my love of science and learning and taught me how to think.

In 1900, Rose married Elick Bloomberg, who arrived in America in 1896 as a twenty-year-old. Two years later he filed his intention to become an American citizen, “renouncing allegiance to foreign sovereigns, especially and particularly to Nicholas II Czar of Russia.” Elick and Rose also took their honeymoon in Washington, DC. We still have the porcelain bowl with a color image of the White House they brought back to grace their home. Together, they raised six children.

Grandpa Elick was learned in the Old Testament, Jewish history, and liturgy. For decades, he was the Torah reader at Chelsea’s Walnut Street shul. Though he served variously as a peddler, justice of the peace, notary public, and insurance salesman, my sister, Marjorie, and I knew him as a teacher, strongly committed to Jewish learning. While we were growing up, he earned his living preparing boys for bar mitzvah. Students often came and went when we visited. Sometimes we heard their lessons from another room.

Rose’s father, Gedalia Bernstein, was one of the first Jewish residents of Chelsea and a founder of the first local yeshiva. Rose’s sister Sarah was also a pioneer, an advocate for the legalization of birth control and a supporter of Margaret Sanger, a leader in the movement. When Sanger was standing trial in federal district court in 1916 for circulating birth control information, she wrote and signed a letter to Aunt Sarah thanking her for her “interest and financial help” and imploring her to do what she could to “keep up the agitation” by writing to the district attorney, the president, and the judge. It’s fair to say that our family’s commitment to women’s rights and the responsibility to participate in public life dates back at least one hundred years.

Our family story is very much an American one. Our ancestors were courageous in uprooting themselves from everything they knew, risking ocean crossings and making new homes in a strange new land. They and their families came from shtetls in Russia’s Pale of Settlement, the area to which Jews were restricted. Their towns in Kovno, Vilna, and Grodno are listed in the Valley of Lost Communities at Yad Vashem, remembered because the Jews living there perished in the Holocaust.

No matter how challenging or dangerous their lives were elsewhere, it was not easy to start over. My parents didn’t talk about the struggles their parents and grandparents faced as immigrants, or the persecution they may have faced in their home country. But they did teach us that we had a responsibility to give back to the country that embraced our ancestors and that made our lives possible. I remember asking my father why he was writing a $25 or $50 check—which was a lot of money for us—to the NAACP, and I’ve always remembered what he told me: discrimination against anyone is discrimination against everyone. I have tried to live up to his example, and the values my grandparents and great-grandparents exemplified, through my work in public service, philanthropy, and advocacy for a just and humane world.

My ancestors came to America at a time when immigration—to my great good fortune—was virtually unrestricted. Those days are long gone, and national security demands that we control our borders, but that does not preclude a reasonable and generous immigration policy. I’ve worked my entire public career to promote legislation that will allow current and future generations of immigrants to contribute to this wonderful nation into which I was born.

I was privileged to serve as mayor of the world’s immigrant capital for twelve years. I doubt that my grandparents and great-grandparents could ever have imagined that one day a member of our family would hold that position. I hope that I am repaying some of the debt I owe them by working to keep America’s opportunities open to all people, of all colors, faiths, orientations, and backgrounds. We owe a similar debt to our shared American future. There is no way to tell which New York City schoolchild or, eventually, which of their children or grandchildren, will lead this city and country in her or his own time—but I know we are all made greater because one of them will.

__________________

* I would like to thank my sister, Marjorie Bloomberg Tiven, whose archival research and commitment to our family history made it possible to write this piece.

Joseph Bower

Professor Joseph Bower taught for over fifty years at the Harvard Business School.

My memories of my grandfather Morris Turitz begin with a friendly, hard-of-hearing old man in a dark three-piece suit and a tie sitting in an armchair in the library of my parents’ home smoking smelly cigars. He lived with us in our apartment on Central Park West. He devoted a great deal of time to reading the daily Forward and later the Compass. He was kind to me and taught me to play pinochle, a game he played when friends of his would visit.

He presided over a family of seven children, whom he was very proud of. He was also a central character in his larger extended family—including among his cousins, whom I would meet at large Passover Seders on the second night when everyone spoke Hebrew out loud at their own pace—and which went on forever, to my young eyes. On rare occasions I was taken to a large meeting of cousins—the Hirsch Mordechai Society—named after my grandfather’s grandfather, which consisted of Vilna cousins—the Sachses, Markses, Zizmars, Levins, and Turitzes. This group of families still communicates in a network of many hundreds.

Later, well after my grandfather died in his late eighties, I learned of his accomplishments and wondered why I never had been told about him earlier so that I could learn more. Born in Vilna, Lithuania, he grew up moving among nearby towns as his father’s income waxed and mostly waned. In his memoirs, he remembers mostly his Talmud studies and his family’s economic struggles. Evidently, he was a brilliant student, for his progress was marked by increasingly important heders and yeshiva. After he survived a serious illness that left him deaf in one ear, Morris’s father bought him a ticket to Boston.

There begins his impressive American story. Starting as a peddler—selling sundries to the goyim acted as his English immersion training—the yeshiva bocher worked to support his mother and sisters. Soon he gave that up to work for tiny wages in hellish conditions at a felt hat factory in Haverhill, Massachusetts. In 1891, he and other workers organized the workmen’s educational society, which grew into the Socialist Labor Party and eventually into one of the foundations of the American socialist movement.

In order to improve his circumstances, this socialist learned cigar making and then decided to go into business for himself. With that foundation he moved to start a business distributing kerosene. He was able to make more money and then eventually to become a US citizen.

My grandfather continued to be very active in the socialism movement, taking part in the establishment of a Yiddish newspaper called Emmes (Truth). Later he was a delegate from Boston to the convention that established the Jewish daily Forward, and was active in the meeting when Eugene Debs established social democracy. Later he helped to found the ILGWU. David Dubinsky would eulogize Papa at his funeral.

My grandfather married in 1899, and because his wife was longing for New York, they moved there soon after, both to make her happy and to be with the big shots of the socialist movement in New York City. Selling his business and moving to New York seemed crazy, but he did it. A friend of his in Boston had a business supplying clean towels as a service to barbershops. His friend made good money with this business, so my grandfather decided it was something he could try. Lacking experience, he looked for a partner. His choice would end up becoming a lifelong friend. They worked together for twenty-eight years building strong businesses that provided the core of what became known as Consolidated Laundries.

Many milestones marked their progress, but three in particular stand out. Through a conversation with a customer sitting in a barber chair, the idea of renting linen for restaurants as another service business came up. Rapid expansion followed. Milestone two was the building of a purpose-built laundry service that had water-based air cooling—a first for the laundry industry and a model studied by the Labor Department and visitors from around the world. The business also paid a minimum wage well above the industry standard and provided stools for the workers—“Why should they stand if they can sit?” They also had paid vacations, and their drivers and foremen were given stock in the company. Grandpa had a Cadillac, but he parked it blocks from the plant so as not to show off in front of the workers.

After World War I, there were attempts at industry consolidation, but it wasn’t until the Roaring Twenties that a merger finally occurred with an investment bank. My grandfather sold his business, took his family on a magnificent trip to Europe, and never looked back. Social causes and politics were always his focus. The crash lessened his wealth, but his support for workers and progressive politics remained a constant for the remainder of his life. That and his family.

His wife and children were the jewels in his crown. My mother was the oldest of his seven children. Interested in music, she was brought up with tutors, then studied at the Institute of Musical Art (later refer...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Our Journey

- The Changers

- The Lovers

- The Originals

- The Rescuers

- The Seekers

- The Strivers

- The Survivors

- The Trailblazers

- The Undocumented

- The Institutions

- Write Your Own Story

- American Renewal

- Acknowledgments