eBook - ePub

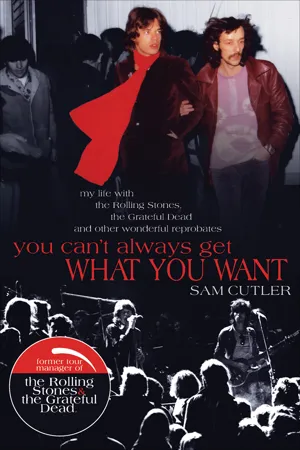

You Can't Always Get What You Want

My Life with the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead and Other Wonderful Reprobates

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

You Can't Always Get What You Want

My Life with the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead and Other Wonderful Reprobates

About this book

A "straight-dope, tell-all account" of touring with two of the world's greatest bands of the 60s and 70s—A "fast-moving narrative of rock-n-roll excess" (

Publishers Weekly).

In this all-access memoir of the psychedelic era, Sam Cutler recounts his life as tour manager for the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead—whom he calls the yin and yang of bands. After working with the Rolling Stones at their historic Hyde Park concert in 1969, Sam managed their American tour later that year, when he famously dubbed them "The Greatest Rock Band in the World." And he was caught in the middle as their triumph took a tragic turn during a free concert at the Altamont Speedway in California, where a man in the crowd was killed by the Hell's Angels.

After that, Sam took up with the fun-loving Grateful Dead, managing their tours and finances, and taking part in their endless hijinks on the road. With intimate portraits of other stars of the time—including Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, the Band, the Allman Brothers, Pink Floyd, and Eric Clapton—this memoir is a treasure trove of insights and anecdotes that bring some of rock's greatest legends to life.

In this all-access memoir of the psychedelic era, Sam Cutler recounts his life as tour manager for the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead—whom he calls the yin and yang of bands. After working with the Rolling Stones at their historic Hyde Park concert in 1969, Sam managed their American tour later that year, when he famously dubbed them "The Greatest Rock Band in the World." And he was caught in the middle as their triumph took a tragic turn during a free concert at the Altamont Speedway in California, where a man in the crowd was killed by the Hell's Angels.

After that, Sam took up with the fun-loving Grateful Dead, managing their tours and finances, and taking part in their endless hijinks on the road. With intimate portraits of other stars of the time—including Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, the Band, the Allman Brothers, Pink Floyd, and Eric Clapton—this memoir is a treasure trove of insights and anecdotes that bring some of rock's greatest legends to life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access You Can't Always Get What You Want by Sam Cutler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Biografie in ambito musicale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781554906963Subtopic

Biografie in ambito musicaleCHAPTER 4

Standing in the shadows

THE IMMEDIATE EFFECT OF HAVING taken LSD was a subtle diminution of my self-confidence. My own understanding of the world now seemed inadequate and I realized that I was misinformed about the essentially subjective nature of personal reality. It was as if my inner inmate had taken over the asylum of consciousness, and for a while confusion reigned as I struggled to reconcile what I had just experienced with my daily life as a teacher.

After a two-year struggle between my inner pleasure-demons and the outer reality of the daily grind, I left teaching because I couldn’t live on the paltry salary — and I couldn’t stand most of the other teachers.

To be frank, indulgence and hedonism seemed more attractive and much more fun. My initial enthusiasm and idealism had been blown away and had foundered on the inherently conservative policies of the educational establishment. The kids might have been interesting, but the adults were a bore. After I left, I missed the kids. I hope to think that the kids missed me.

I moved into a shared apartment with friends in Inverness Terrace in the heart of London and put my energies into music business activities and that vital component of a young man’s life: having fun.

London was smoking, literally and metaphorically. My new flat was round the corner from Queensway tube station and across the road stretched the green of Hyde Park. There I would notice small groups dressed like effete Regency dandies in multicolored clothing, lounging and discreetly smoking joints. It was easy to simply walk up to a group of strangers in the park, sit down and join the languid conversation. People were happy to share what they had as long as they didn’t think you were boring — or that you were a police officer.

Richmond Park, to the west of London, had a large herd of deer. On the mornings after rain we would go to the park and search for psychedelic mushrooms, which grew on feces the deer had thoughtfully spread through the park. The small bell-shaped mushrooms sprouted, tottering top-heavy on a spindly stem. They were easy to find.

In the early morning mist, young people would tromp through the wet grass, laughing and giggling. The authorities were oblivious to the early birds catching these new worms.

People began to drive to Wales to collect mushrooms; there they grew in abundance. A substantial movement of young city-dwellers went to live in the Welsh valleys. Teepees sprouted between the hills, which had been depopulated for a generation as the farms had become economically unviable. Afghan and Lebanese hashish were readily available throughout London and the Home Counties, and as you walked in the Kensington Market or the Kings Road you could smell the joints being smoked. Fashions were getting wilder by the minute and the girls never looked more beautiful.

A generational shift was happening; those who had fought in World War II took political power. Student politics in England were abuzz with the events in Paris, where in May 1968 young people had been supported by trade unionists in violent demonstrations and in the seizure of universities and factories. American policy in Vietnam radicalized even jaded pop stars, and Mick Jagger, to his eternal credit, participated in a huge demonstration against the Vietnam War, where I walked holding the lead banner with my old friend from Paris, Hubert. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol was everywhere.

In Notting Hill I could see the changes that were occurring. People seemed to have lost that grim unhappiness with which the English face the world. In the London streets strange slogans would appear on walls. I remember seeing: “If voting made any difference they’d make it illegal,” and “Hashish is the new opium of the people.”

Radical alternatives to the old systems were the subject upon everyone’s lips and young people began to look at the music industry and speculate about a fresh approach. Old people, it seemed to us, ran the music business with their arrogant posing and big cigars. The Larry Barnes/Tito Burns/Larry Parnell school of management seemed hopelessly old-fashioned, with elderly “squares” in control. Some of the traditional managers not only had dubious business morals, but also came across as if they’d been doing things the same way for a million years. They appeared to us like living fossils.

We weren’t totally naive. We knew that several of these men loved to control their artists in every sense, and were little better than sexual predators. Collecting a stable of young men to “groom” as stars seemed to be their main ambition. We viewed the whole thing as highly suspicious.

For a while it was all drainpipe trousers on good-looking boys with bulging crotches, who fed the masses a steady diet of musical pap that featured prominently on TV and in the charts. It was the “sore-bottom” school of rock; when we saw the “artists” we’d snigger: “One up the bum, no harm done.”

None of this affected those who wanted to make alternative music: acts like the Soft Machine, Pink Floyd, and Arthur Brown, who led the Crazy World of Arthur Brown. Bands like these were far too “out there” for the older men who ran the music business. They were terrified that any involvement with druggy long-hair acts might bring a whiff of scandal into their otherwise socially acceptable lives.

Alternative music, initially at least, had to have alternative management, though it wasn’t long before the professional sharks of the industry got their teeth into some of the psychedelic bands. Thankfully, by that time, I was happily in America.

All Saints Church Hall, off Westbourne Grove in Notting Hill, was one of the very first alternative music scenes. Musicians would play for fun and people would make a contribution to get in the door. I happily worked there for free, like everyone else. All Saints Hall became a legendary venue while it lasted, with people such as Arthur Brown, Charlie Watts, and many others playing for appreciative audiences who packed the place. It was there that I became friendly with Nick Mason, Pink Floyd’s drummer.

For a while I thought I was madly in love with the sister of the woman who would eventually marry Nick, but then I was in love with most of the girls around the music scene. They were divine and desirable, and I wanted to love them all! I was effectively “in love with love,” and still working out what I should do with my heart.

Pink Floyd always had the most spectacular women in attendance, especially their first singer and nominal frontman, Syd Barrett. Whenever I saw Syd, who could look like a frightened deer caught in a car’s headlights, he would be accompanied by a delectable-looking creature who would waft about looking divine. We would all sigh happily for him and his good fortune. The girls around the Floyd were the perfect psychedelic companions for the journey; wonderful givers of love and light whom we would daydream about contentedly.

I used to watch as all these ethereal women, without exception, would initially set their sights on Syd. As far as I could tell, he paid them very little heed, occupied with his own whimsical inner workings, though it was plain that he was in need of their care. He was childlike, what we would unkindly call a “space cadet.” I always doubted whether the man was capable of cooking himself a piece of toast, but when I first knew him he could play guitar quite well. I can remember him calling out chord changes to the band as they worked on new material.

There was no doubt that Syd was the first, albeit reluctant, star of the English psychedelic scene. He had a strangeness about him, and would stare intently and appear disproportionately interested in the most inconsequential thing. “Mad as a March Hare,” my girlfriend at the time said (and she would have known, as she was resident at Kingsley Hall and being treated by Ronnie Laing, world-renowned psychiatric expert in “human madness”). Mad or not, Syd kept his guitar in tune, although sometimes he’d forget to play the bloody thing.

Friends told me how he took them to the country in his car, and on the way, Syd stopped and got out. He simply walked away. By the time they realized what was happening, Syd was unable to be found and they had to abandon the car. When they saw Syd again he had no memory of even going on the journey.

No one had the heart to give Syd a hard time because it was apparent that he had no idea what was happening. He was an innocent, Syd. The girls did their best to nurture and protect him, until Syd just wasn’t “there” anymore, and there was nothing anyone could do for him.

The other guys in Pink Floyd were unbelievably kind to Syd, given the circumstances. What had once been a bright and shining diamond of a man devolved into a dull drugged-out pastiche. Everyone on the scene found it unbelievably moving and sad, yet there was no one who could have helped, though many tried.

I had been turned on to All Saints Hall by my crazy and wonderful girlfriend, and loved it so much that I took one of my own friends, Ron Geesin, to experience what was going on. Ron and I had met through a mutual friend and had hit it off immediately, which may well have been because I loved his music, a crazed twist on the theater of cruelty. He was one “out there” guy.

Ron was a skilled classical musician, but his personal tastes extended to manic instrumentals and odd sound effects, which he graced with absurdist lyrics delivered in an unfathomable Scottish accent. The whole effect was scary and disconcerting. To witness him play the piano with demented passion was to experience a vision of such deep alienation it made one pale with fear. Yet Ron was the most sociable of people, and once the musicians in the Floyd got to know him they loved him for his peculiar eccentricities. We all became firm friends.

Ron wasn’t a drug user, refusing to even smoke a joint, but incredibly, he was able to relate to the Floyd’s music, and soon became close to both keyboardist Rick Wright and bassist Roger Waters. Ron played a significant part in opening up the Floyd’s approach to music, and his influence can be heard all the way through from their first LP, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, released in 1967, to The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Animals (1977), and The Wall (1979). The Wall may be credited to Roger Waters and the Floyd, but much of its alienated, angst-driven madness came from the early surrealist influence of my friend Ron.

Both Nick Mason and Ron Geesin were to help me with one of my own music projects, for which I was eternally grateful, as their involvement lent my experiment a certain gravitas. Some friends had decided to form a band called Screw, a punk band, more than a decade before Malcolm McLaren got involved with the Sex Pistols and well before anybody had a clue what “punk” actually was. Ron and Nick found it both awful and mesmerizing. The music we made was fun and irreverent and it sank without trace.

Screw was one of the only bands I have ever seen force an audience into dumb and befuddled silent surrender. After hearing Screw play, people simply didn’t have a clue what to think, let alone say. Screw rendered them appalled and speechless. This was, we thought at the time, a considerable achievement.

Even John Peel, the well-regarded DJ who played all kinds of strange music on his bbc radio show, was dumbstruck by Screw. I invited John to one of their gigs and during the set, Chris Turner, the harmonica player, overdid things a bit. Blood spurted from his lips, raining all over the stage. Pete Hossell, the lead singer, went to help and got blood on his hands and on the microphone. It looked pretty serious and afterwards a concerned Peel went backstage to see if he could help. He was shocked to see Pete Hossell washing Chris’s bleeding lips with one of his dirty socks dipped in beer, swigging from the bottle as he did it, appearing totally unconcerned.

Chris was amazing: he played killer blues harp and sometimes spat out broken teeth and lashings of blood as he took his solos; audiences were suitably horrified. It often looked as if the man was bleeding to death while he was playing. Several times, Chris had to be revived on stage and a promoter once called an ambulance because he was convinced Chris had lost too much blood. (It was all an act, of course, with Chris chewing on blood capsules, but Screw was very convincing and few people knew the truth.)

The Floyd’s Nick Mason helped to produce a few Screw tracks at Lansdowne Studios in London on May 13, 1969. The tracks then languished in a tape store for some thirty years. I no longer remember what it was I told Nick in order to get him to help with such an unlikely project, and goodness knows why Ron Geesin did the tape transfer and mastering. But Ron always had a soft spot for anything that was out of the ordinary and vaguely shocking. He was the only man I knew who liked the Dagenham Girl Pipers, a London-based band of female bagpipers.

Upon reflection, Nick Mason probably got involved because Screw represented a break from the complexity and cleverness of the Floyd. Their offensive approach was probably quite refreshing to Nick and a welcome antidote to Roger Waters continually telling him what to do.

I managed to get Screw on the bill of the free show the Rolling Stones did in Hyde Park (more on that subject later). At that gig the band played for some half a million people and I remember jazz musician Alexis Korner watching them from the side of the stage and shaking his head in bewildered silence. Soon after I left for America, and thereafter Screw was other people’s concern.

The band was way ahead of its time and suffered a miserable fate. Their co-manager went mad and tried to form a commune in Scotland that only had one devotee, whom he got pregnant. The lead guitarist, Al Kinnear, died young. The drummer, Nick Brotherwood, became a Christian minister. Pete Hossell ended up in São Paulo, Brazil, and Stan Scrivener, the bass player, was never heard of again. The record we made in 1969 was finally released in 2006, in a limited edition of 500 copies on the specialist Shagrat label. It sounded just as crazy as I remembered it.

Another of the London clubs central to the new musical culture was called ufo. It opened just before Christmas 1966, and was a bit of a pit, underneath a cinema in Tottenham Court Road. Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine would play there, and I would dress up in my psychedelic gear and attend with people who seemed to descend from all over England. A German fellow was the house drug dealer and I would sometimes smoke a few hash pipes, drop a trip, and watch black-and-white films projected on the walls all night. Stumbling up the stairs onto Tottenham Court Road at seven on a Sunday morning, still tripping, was quite a strange experience. I used to get away from the whole ufo scene as quickly as I could and go walking for miles through the deserted streets and watch the great city slowly drag itself awake.

As new clubs opened, new managers sprung up to take the place of those who had run the business for too long. Peter Jenner and Andrew King were in the forefront of this new guard and had founded a company called Blackhill Enterprises. I came to their establishment by a roundabout route.

It is a tradition in England that on summer weekends people leave the cities and go to the country, to a house party, or to visit friends. I was invited to spend a weekend at a huge house in the Surrey countryside. The house belonged to Nick Mason’s father-in-law, a well-known and progressive architect.

We arrived somewhere south of Guildford to find forty or fifty people dressed in rainbow colors, all tripping like mad as they strolled through the formal gardens and lounged on the immaculate lawns of a monstrously large red-brick house. It was all terribly civilized in an English way. I remember meeting the owner of the house, who had a gray-white beard and was very gracious and thought that his daughter’s friends were remarkable and interesting. I’m not sure what he thought of me, dressed in my most extraordinary clothes. With a lady friend, I was making clothing for some of London’s new, trendy boutiques and we would buy furnishing fabrics at Liberty’s, a huge shop which sold wild William Morris–designed nineteenth-century fabrics. The fabrics were intended as curtain material, or for covering chairs and furniture, but we used them to make bell-bottomed trousers and jackets for the Kensington Markets. I actually had a suit made from fabric with massive rhododendrons all over it. I’m amazed, looking back, that I was brave enough to wear it. We didn’t sell many clothes, but it was fun.

On this lovely summer’s afternoon in the depths of the English countryside, I talked with Nick Mason and Rick Wright about music, life,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Let ’em Bleed

- Busy Being Born

- Behind the Beat

- No Direction Home

- Standing in the Shadows

- Free Music, English-style

- Thou Art That

- The Stones in the Park

- Firing Allen Klein

- Hurry Up and Wait

- Play That Country Music, White Boy

- The Greatest Rock’n’Roll Band in the World?

- Los Angeles

- Bill Graham

- By the Time we Got to Phoenix

- Mick Taylor

- Trust Me, I’m a Pilot

- A Free Concert

- What You See is What You Get

- The King of Torts

- The Makings of a Dumb Idea

- The Big Apple

- Bringing Home the Bacon

- More Foolish Plans

- Welcome to California

- The Construction of Nightmares

- One Way or Another

- When the Going Gets Tough

- The Death of Meredith Hunter

- Aftermath

- Shelter from the Storm

- Jerry & Janis

- Garcia

- Trust me – I’m a Christian!

- Witness for the Defense

- Yin and Yang

- Cool Conundrums

- Only Whisper and You’ll be Heard

- The Bear

- Loose in America

- Where’s Jimi?

- Don’t Touch Anything

- All Aboard that Train

- Memories are Made of This

- Running Like Clockwork

- The End of the Line

- Whistling in the Graveyard

- An Unsavory Meal

- The Fillmore East

- Europe

- Out of Town Tours

- Don’t Look Back?

- Acknowledgments

- Photos

- About the Author

- Imprint