- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

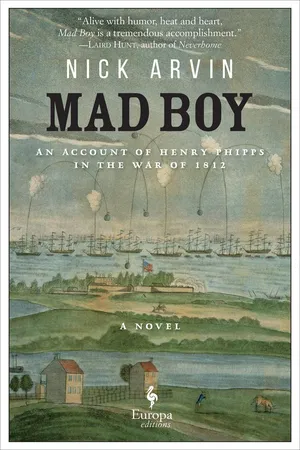

Colorado Book Award Winner for Literary Fiction: "The colorful characters make this account of the War of 1812 a rollicking page-turner" (

Publishers Weekly).

In the early nineteenth century, young Henry Phipps is on a quest to realize his dying mother's last wish: to be buried at sea, surrounded by her family. Not an easy task considering Henry's ne'er-do-well father is in debtors' prison and his comically earnest older brother is busy fighting the redcoats on the battlefields of Maryland.

But Henry's stubborn determination knows no bounds. As he dodges the cannon fire of clashing armies and picks among the ruins of a burning capital, he meets looters, British defectors, renegade slaves, a pregnant maiden in distress, and scoundrels of all types. Mad Boy is at once an antic adventure and a thoroughly convincing work of historical fiction that recreates a young nation's first truly international conflict and a key moment in the history of the emancipation of African American slaves. Entertaining, atmospheric, and touching, it is "a wartime coming-of-age story filled with nonstop action and genuine pathos" ( Kirkus Reviews, starred review).

"This brilliant musket blast of a novel—in which the lucky reader will encounter falling cows, repurposed pickle barrels, fascinating schemes and fabulous schemers—is alive with humor, heat and heart. Mad Boy is a tremendous accomplishment. Nick Arvin is the real thing." —Laird Hunt, author of Neverhome

In the early nineteenth century, young Henry Phipps is on a quest to realize his dying mother's last wish: to be buried at sea, surrounded by her family. Not an easy task considering Henry's ne'er-do-well father is in debtors' prison and his comically earnest older brother is busy fighting the redcoats on the battlefields of Maryland.

But Henry's stubborn determination knows no bounds. As he dodges the cannon fire of clashing armies and picks among the ruins of a burning capital, he meets looters, British defectors, renegade slaves, a pregnant maiden in distress, and scoundrels of all types. Mad Boy is at once an antic adventure and a thoroughly convincing work of historical fiction that recreates a young nation's first truly international conflict and a key moment in the history of the emancipation of African American slaves. Entertaining, atmospheric, and touching, it is "a wartime coming-of-age story filled with nonstop action and genuine pathos" ( Kirkus Reviews, starred review).

"This brilliant musket blast of a novel—in which the lucky reader will encounter falling cows, repurposed pickle barrels, fascinating schemes and fabulous schemers—is alive with humor, heat and heart. Mad Boy is a tremendous accomplishment. Nick Arvin is the real thing." —Laird Hunt, author of Neverhome

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mad Boy by Nick Arvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Henry Phipps runs through the shadows under great trees. He’s angry. Someone has lied—the slave Radnor has lied to Henry, or someone has lied to Radnor: some liar has lied to someone a terrible lie. He runs through wet heat and spongy mud, through clouds of gnats and sprays of pale flowers, a small boy, lean like a figure cut from a length of wood too thin for the intended shape. He wears a shirt that’s scarcely more than sacking with buttons, trousers patched in several places and cinched by a rope belt, boots with a hole in one toe, no hat.

When a bramble scratches his leg, he stops to yell at the plant and kick it. Then he runs on.

Old forest still covers much of the land between the Chesapeake and the Potomac, and America has been at war with Britain for two of Henry’s ten years, mostly losing. From ahead drifts the sound of an English voice, which Henry would notice if not for the noise of his own breath, rushing blood, fury.

Why would Radnor lie? Who would lie to Radnor? Henry cannot fathom. He jumped to his feet and raced away before Radnor finished explaining. Henry wants to talk to Mother; Mother will know what to do. Henry is so outraged and wrathful that he gives only contempt to the idea that what Radnor said might be true—that Henry’s brother, Franklin, is dead.

He runs under hickories and sycamores, not slowing as the land slopes upward, trying to go yet faster against the ache in his legs.

He careens into a clearing, stumbles, stops. Before him is a round-eyed, jug-eared man holding a musket and wearing a brass-buttoned wool jacket, well-worn, dirty ruddy-pink. Behind this man, scattered about the open meadow, are some three dozen soldiers in similar coats, like a flight of faded cardinals.

They are of course redcoats. A couple of months ago Henry’s father was sent to the debtor’s prison in Baltimore, but previous to this setback Father had often traveled to Washington, Alexandria, Annapolis, and Baltimore, where he drank whiskey and played faro. He always returned poorer but bearing the latest news, and for two years the news has been of the redcoat raids up and down the Chesapeake, capturing food and goods, destroying farms, taking away slaves.

The jug-eared redcoat, who looks not yet eighteen, yelps, fumbles for the musket on his shoulder, catches a heel, falls on the seat of his patched trousers.

The other redcoats turn and stare. The humid air lies quiet. The ironwork of the British muskets shines like Spanish dollars. The stocks are painted vermillion. Among the British—surprising Henry amid his surprise—are a few black-skinned soldiers. The redcoats span a long, narrow meadow, cut across by a zigzag fence. Out of sight, behind the trees, is a house, and Henry knows the family there a little: the Jeffery family, they keep several cows, pigs, goats, and an uncommon number of turkeys, which they chase across their tobacco field to peck the horn worms.

One of the redcoats has straddled a she-goat with enormous conical teats and slashed her throat. As he stares at Henry, the throat drizzles, and the goat appears both sleepy-eyed and irate.

Some twenty yards behind the jug-eared soldier, who still sits in the grass, stands a redcoat with a gold epaulet, a brass-tipped black leather scabbard, and a jacket that is redder than the others. In each hand he grips a headless chicken. “Hello there, boy,” he calls. “Hold up.” He looks at the chickens, as if unsure whether to drop them, or throw them, or some other course of action.

Henry, in his surprise, laughs.

Then he turns, jumps for the bushes, and tumbles downhill.

He ends up with his face in branches and dirt. He proceeds sideways through scratching brambles, hoping the redcoats will assume he would continue straight down. He wriggles into a hollow beneath an evergreen and lies panting and trying to swallow his panting.

Behind him the redcoats yell insults at one another. Henry hears the jug-eared soldier call, “Oh, close your hole, egg sucker!” He plods loudly into the brush and trees. “Why run away, boy?” he calls. “Because you’re a spy? A stupid one? Come out, stupid spy! Come out, so I can kill you!” Henry watches him aim his musket to the left, then the right, sigh, turn, amble away.

Henry shifts a branch to see the others. This is exciting. Father said that the British would never come this far inland—but for Father to be proven wrong is a circumstance with many precedents. The British have a trio of donkey carts, loaded with cornmeal, tobacco, dead livestock, whiskey. The redcoats smash up the rails of the fence to make a path for the carts, and they move on in the direction of Mr. Suthers’s house. A black soldier leads the way. Henry wonders idly how long it will take for the Jefferys’ livestock to find the hole in the fence and wander off.

He trails behind the redcoats for a half mile, then turns toward the cabin and Mother, thinking again of what Radnor said. Immediately he’s angry, fears he may weep, runs.

In the grove of black walnut that Henry’s great-great-grandfather planted a hundred years ago the sun casts shivering fawn-spots on the earth. Henry runs through, footfalls padded by moss. Great-great-grandfather believed his heirs would appreciate the nuts and might use the wood for gunstocks or fencing. He would have been disappointed. His progeny did nothing with the walnuts and instead established and advanced a nearly mythical reputation for dissolute laziness, dependence on neighbors’ charity, and love of whiskey and gambling. Henry’s great-grandfather and grandfather sold away slaves to pay debts, and the Phippses remained too placid or shiftless or—arguably—stupid to rebuild their accounts by working the land or nail-making or shingle-cutting or ropewalking or some other craft. After Henry’s grandfather died of a wart that became gangrenous, the estate passed to Henry’s father. Father, in due time, gambled away the land. General opinion held that the only wonder was it had taken so long.

Father was forced to move the family out of the big house to the cabin, and Henry took his first breaths in a borning room built on the side of the cabin. It is the cabin he approaches now. The borning room is gone, after its roof leaked for years, and finally its rotted walls were pulled apart for firewood. What remains is the one-room cabin with the hearth along one wall, beds along two others, a table and benches in the middle. The cabin is built into the side of a hill, and the cabin roof merges directly into the grassy hilltop. Henry has carried buckets up the hillside many times to extinguish fires in the cabin’s bark roof and in the clay-and-stick chimney. Most of the cabin has burned and been replaced at one time or another, except for the back wall, which is integral with the hill and faced with granite. When Mother is sick with the black spirit, she lies abed on her side, facing the granite stones, gripping her left thumb in her right hand. Where the chinking between the granite stones has come free a worm or grub or root sometimes noses through.

Nearby a square-doored cellar is dug into the hillside, and next to it stands a chicken hutch. Slouching opposite the hill is a barn—someone many years ago laid the stone foundation for a proper barn, but the barn itself is a low, leaning, sagging-roofed, provisional structure. A couple dozen chickens peck in the sun-blasted dust, while off to one side lies a vegetable garden surrounded by a jumbled fence of sticks and bits of string, which the rabbits wander through at will. Beyond, wrapping around one side of the hill, is a field of several uneven acres where the biggest stumps have never been removed. Shafts of corn stand out here and there, but much of it is weeds.

As Henry comes up, Mother stands in the garden. She’s not working, only standing, talking to herself.

Henry, who has not considered that what Radnor said might be true, sees Mother, and is forced to consider. It is in the way she shapes her body, somehow proudly downward. Grief and fear clamp a hold on Henry. Grief for his brother, but also the choking fear that this may make Mother ill.

But she turns to him, says his name, and he knows, by the fact that she speaks, that she will not be sick, not right now.

All this he sees in a second as he rushes across the yard.

He becomes furious again. When Mother tries to clutch him, he escapes to run round and round the garden, screaming.

“Eat, Henry,” Mother says, dipping a bowl of succotash from the kettle. She brings it to him at the table. “Eating can only do you good, and we must have our strength for traveling.”

They will go to Baltimore, she said when he stopped running and screaming.

Mother talks without stopping. “Eat all you can. I hate to think what we will leave behind. But this is not the place for us anymore, is it? That’s plain. ‘For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.’”

Henry only recently came to understand that although Mother sometimes quotes the Bible, she doesn’t particularly believe in it. It’s ridiculous, she told him, but it’s handy. Henry eats his succotash. He has already decided that he thinks Franklin is still alive.

A mounted soldier riding messages from Washington to Annapolis stopped at the Sutherses’ house yesterday and left a letter, addressed to Mother. No one in the Suthers household bothered to pass the letter along until today, when they sent Radnor with it. Written by a soldier in Franklin’s regiment, the letter said, General Winder has ordered no news of a military nature of any kind should be provided to civilians in this time of war, but I am writing to you in confidence because I believe that you must be informed that your son, Franklin Phipps, has been captured in desertion in the city of Alexandria and sentenced by the court...

Table of contents

- PRAISE

- ALSO BY NICK ARVIN

- MAD BOY

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR