![]()

To someone Else

![]()

One day it was still December. Especially in Leeds, where winter has been underway for such a long time that nobody is old enough to have seen what came before. It snowed all day, except for a brief autumnal parenthesis in August that stirred the leaves a little and then went back to whence it had come, like a warm-up band before the headliner.

In Leeds anything that is not winter is a warm-up band that screams itself hoarse for two minutes and then dies. Then come the dramatic snowstorms that beat the ground like curses and conspire against the reckless lyricism of the tiny fuchsias blossoming in the park. Give them a round of applause! Encore.

Leeds winters are terribly self-absorbed; each one wants to be colder than its predecessor and purports to be the last winter ever. It unleashes a lethal wind full of the short sharp vowels of northern Englishmen but even harsher, and anyway, neither one of them speaks to me.

To think that it’s not winter people fear, but the inferno, in all its fiery warmth. I’d gladly swap one for the other, winter for inferno, if life could be managed like one of my Chinese exercises.

On the rare occasions that I left the house, an icy muzzle immobilized my jaw and the wind whipped my umbrella inside out, tore it from my hands, dragged it meters down the road, and dumped it crippled in the gutter, its ribs up in the air like broken legs. And yet the English persisted in going out in their short trousers and cotton blazers, their shoes and mouths open, wearing the same wide smiles as they had in August, with the same long strides, the same relaxed way of chatting with each other, drawing the syllables out in their mouths, delivering them without haste to the freezing air where they were transformed into steam. Naturally, their umbrellas never broke.

That December day, just back from an exhausting bout of shopping on Briggate, I threw my brand new magenta jacket into a dumpster on Christopher Road.

That’s the street I live on, one of those streets whose whereabouts you always have to explain to people, and even you can never be sure where it is because it’s identical to the street before it and the one after, and also because the second you get to Christopher Road denial of its sheer ugliness pushes you onward. It’s so ugly, Christopher Road is, that it qualifies as proof of God’s nonexistence. Its gaunt red-brick houses to start with, each one the same as the last, each one with its black metal door like the doors of isolation cells; then the bags of garbage tossed out beside wheelies; the sweeping panorama over the takeaways on Woodhouse Street, which crosses Christopher Road, though no street in its right mind would ever choose to do so.

To the right you can admire Tom’s £3-only fish chip shop, and feast your eyes on neon-blazoned kebab shops. To the left, there’s Nino’s one-quid pizza slices, and down the road, chicken and bamboo shoots or fried seaweed at the Chinese all-nighter.

Then there’s that opening-credits darkness, like when you’re sitting in the cinema, anxiously waiting for a movie to start. But on Christopher Road nothing ever starts. If anything, it ends. Everything ends, even things that have never started. Food, for instance, goes bad even before you open it, because there are blackouts all the time; flowers die before they’ve bloomed because there’s no sun; fetuses have a naughty habit of strangling themselves with the placenta.

It was originally a workers’ village. The factory was the center of the town, then came the workers’ houses, and then the church. Everything was built with an eye to saving money on materials and aesthetics, and since it cost less, all the houses went up instead of out, every one of them three narrow stories high, like so many droll towers of Babel to get to the devil. The factory is an elementary school now. When the bell rings, it releases hoards of baby bag-snatchers into the streets.

The church, on the other hand, is still a church. Tall and dark, its gothic head watches over the flock of headstones. But I’m the only one who ever goes there—it’s been deconsecrated, and the deceased are forgotten to the world. I go there to spy on the dreams of the dead, and to lop the tops off of flowers that sprout there by mistake. No one brings them there to honor anybody’s memory. In fact, remembering is strictly forbidden: thornbush extends like wrinkles over the headstones to hide the names.

But sometimes, despite everything, I find flowers underfoot as I make my way between the weeds, the thornbushes, and the slumbering snakes. There! A small stain of innocent baby blue resting in the scrub’s old-lady hands, a splash of beauty in that spin-dryer of misery and death. A provocation is what it is, and snip, like the fairy that nobody dares invite to the fairytale party I cut it off without mercy.

Then I return home.

You’re thinking that Christopher Road is the last place to set a novel, let alone the story of one’s life, but looking at it now on the page, I see myself there clear as anything, like in a school pic.

I’m the one with the big nose and the long black hair. My complexion lighter than light. No, further over there, to the right, I mean the one with the bangs and the green eyes. Can you see me or not? The one rummaging in a dumpster, yeah, there.

The story of my life? Hardly. My life has no story; it has distortions in place of stories. Deep craters full of sand where stories should be, that’s what my life has, like the ones on the moon, the ones that looked like eyes, nose, and a mouth when you were a kid.

Zoom in on me, dark-haired with bangs, as I toss my magenta jacket. Snow had transformed the shopping bags into twee little snowmen. And right at that moment, as I was shoving my jacket into the dumpster, I saw a dress. A crumpled forest green dress with white buttons poking out from under a plastic Sainsbury’s bag. One long sleeve extended like a green snake over a little yellow plastic stool on the right. On the left it didn’t have a sleeve.

It made me think of one afternoon so long ago and so different from that day that remembering it was like inventing it all over again. My mother is studying the label of a black sweater with rhinestones, because back then she still bought clothes. We’re at the White Rose Shopping Center, it’s raining outside, and, all excited, I’m telling her about my first Chinese lesson.

“And there are tones! Isn’t it absurd? I mean, depending on the tone you use, the word ‘ma’ can mean ‘mummy,’ or ‘insult,’ or ‘horse,’ or ‘cannabis!’”

“Can you read what’s on the label, dear? It’s so small.”

And, concentrating on the hieroglyphic of the basin with the hand inside it, I go: “Hand wash.”

“No, I mean the fabric.”

“100% angora.”

“Oh really! I’m going to try it on.”

“What about this one?”

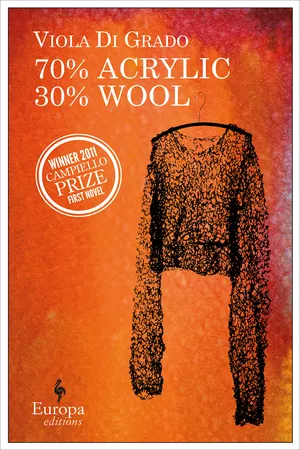

She grabs the white turtleneck sweater and turns the collar out: “Why, no, dear. 70% acrylic.”

I fished the green dress out of the dumpster. It was long, large, made of coarse cotton and as shapeless as a garbage bag. It had a high-buttoned neck, and the top three buttons skewed to the right and were stitched with a different kind of thread. The neck was clearly too tight. I put it in my bag. Then I noticed another dress that had been hiding beneath the one I’d taken. It was red, made of heavy wool. It, too, had only one very long sleeve and a plunging neckline that ran all th...