- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Arthur and the Lost Kingdoms

About this book

A

"fascinating historical detective work" that pins down the real story of the legendary medieval king and the court of Camelot (

Spectator).

The Holy Grail, the kingdom of Camelot, the Knights of the Round Table, and the magical sword Excalibur are all key ingredients of the legends surrounding King Arthur. But who was he really, where did he come from, and how much of what we read about him in stories that date back to the Dark Ages is true? So far, historians have failed to show that King Arthur really existed at all, and for a good reason—they have been looking in the wrong place.

In this "vivid and thought-provoking" book, Alistair Moffat shatters all existing assumptions about Britain's most enigmatic hero ( Birmingham Evening Mail). With references to literary sources and historical documents, as well as archeology and the ancient names of rivers, hills, and forts, he strips away a thousand years of myth to unveil the real King Arthur. And in doing so, he solves one of the greatest riddles of them all—the site of Camelot itself.

"A virtuoso performance." — Cardiff Western Mail

"Crammed with detail and follows a broad sweep across much of our history from the Ice Age to the Middle Ages." — The Scotsman

The Holy Grail, the kingdom of Camelot, the Knights of the Round Table, and the magical sword Excalibur are all key ingredients of the legends surrounding King Arthur. But who was he really, where did he come from, and how much of what we read about him in stories that date back to the Dark Ages is true? So far, historians have failed to show that King Arthur really existed at all, and for a good reason—they have been looking in the wrong place.

In this "vivid and thought-provoking" book, Alistair Moffat shatters all existing assumptions about Britain's most enigmatic hero ( Birmingham Evening Mail). With references to literary sources and historical documents, as well as archeology and the ancient names of rivers, hills, and forts, he strips away a thousand years of myth to unveil the real King Arthur. And in doing so, he solves one of the greatest riddles of them all—the site of Camelot itself.

"A virtuoso performance." — Cardiff Western Mail

"Crammed with detail and follows a broad sweep across much of our history from the Ice Age to the Middle Ages." — The Scotsman

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

ANOTHER RIVER

This is a story of Britain; a tale of the events and circumstances that first defined Britishness, resisted homogeneity and made these islands a collection of nations whose

languages have survived to describe several versions of our present, and remember a past different from the one we think we know. It is also the story of a time when written memory fails us and

when archaeology is imprecise; what historians have called our Dark Ages.

This is the story of Arthur; perhaps the most famous story we tell ourselves, certainly the most mysterious and least historical. He was a heroic figure who cast a mighty shadow over our

history, colouring our sense of ourselves more deeply than any other. And yet he is elusive, barely recorded on paper or vellum and certainly not noted in the chronicles of his enemies, those who

eventually won the War for Britain. But Arthur touched the landscape, and it remembered him.

That is where I came across his story, in the hills and valleys of Britain. At first I did not realize what I was looking at. When I began thinking seriously about this book, what I had in mind

was something quite different. Originally I intended a miniature. Richly decorated, vividly coloured, pungent and full of interest perhaps, but a miniature for all that.

I was born and brought up in Kelso, a small town in the Scottish Border country and, quite simply, I wanted to write a history of the place because it will always mean home

for me and the sight of it still warms me even after thirty years of absence. I had no ambition past capturing something of the essence of Kelso by setting down in reasonable order a chronicle of

the years of its existence.

But almost as soon as I began my research, a series of unexpected and puzzling questions threatened to detour my straightforward purpose. Kelso first comes on written record in 1128 when

monastic clerks drew up the abbey’s foundation charter. All of the villages, churches and farms detailed in the document must have been going concerns well before that date, and so I set

about finding earlier references to the town and its hinterland. Scottish medieval records are notoriously scant but I was still surprised at the paucity of material. I could find only one mention

of Kelso before 1128 in any sort of document at all. This was an English translation of a poem written in Edinburgh around 600. Not in Gaelic as you might ignorantly expect, or Latin, but in an

ancient form of Welsh. Known as ‘The Gododdin’1 it tells the story of the warriors of King Mynyddawg and their disastrous expedition to

fight the Angles at Catterick in North Yorkshire. One of the Gododdin princes is named as Catrawt of Calchvyndd. I realized immediately that this is the oldest name for Kelso and also its

derivation. In Old Welsh, Calchvyndd means ‘chalky height’ and not only is part of the town built on such an outcrop but the street leading to it bears a translation, the Scots name

Chalkheugh Terrace. And in the 1128 charter Kelso is spelled Calchou. Calchvyndd and Kelso are clearly the same place.

But I found myself more than surprised to read the early history of the south of Scotland in Welsh, and more, to read of Welsh- speaking princes, kings and kingdoms in a place I thought I knew

well. Who were these people? Where were these lost kingdoms? It seemed to me that there was another river running.

Catrawt and his Calchvyndd led me to ask many questions, but in particular he suggested place-names as a rich source for the early history of Kelso and the Scottish

Borders. What I found gradually revealed to me was something remarkable: a story of Britain and, more, the historical truth of the most famous secular story in the world, what people miscall the

Legend of King Arthur. Neither a legend nor a king, I found him remembered by the land, in the fields, Xrivers and hills of southern Scotland, and by extension by the people who farmed, knew and

named where they lived. Unremarked by history, little people who walked and worked their lives for generations under Border skies. And also by looking hard at a small place I began to become aware

of a much larger picture until, after a time, I could lift up a map of the Border country and see clearly the watermark of Arthur.

Before I go on to the meat of what I have found, I should make some confessions and assertions. As a historian I am an amateur, in the old sense of loving it, and emphatically not in the new

sense of being sloppy or less than serious. I am certainly not an academic historian, not time-served and with no folio of published papers to act as pencil sketches for the big picture. Anyway,

what academic would want to do something so literally amateurish as to write the history of his home town?2 Aside from a decent education, I only

have two claims to bring to the reader’s attention. The first is simple: since no one asked me to do this, I am not obliged to be anything other than my own man. I care nothing for academic

reputation, the conventional wisdom or the weight of opinion. These researches are founded on common sense and sufficient erudition.

My second claim will take longer to unpack. It directly concerns my interest in the names of places, more properly toponymy, and how my knowledge of all this began.

When I was a little boy in the 1950s my dad took me with him in his van to summer jobs. He was an electrician who worked on Saturday mornings, often going out to the grand houses of the

Borders to fit a plug on a kettle or replace a lightbulb for ancient aristocrats with servants still suspicious of electricity. The toffs, as he labelled them, did not

interest him much but my dad was fascinated by their land and their ability to hang on to it and shape it to their purposes. One Saturday he took me to a place called the Hundy Mundy Tower.

Standing in the dank wood almost completely hidden, it was a chilly, creepy building resembling the gable end of a Gothic cathedral. My dad explained that it was a folly designed to finish a vista

from the windows of a big house. The trees had been planted to add mystery and spurious antiquity. ‘Power,’ he said to me many years later, ‘that is real power; being able to

alter the landscape to suit one man’s idea of a good view and invent a bit of history forbye.’

My dad knew the land around Kelso intimately and we talked a great deal about change, how it could obliterate history and how often the names of their places were all that remained of peoples

who had long vanished into the darkness of the past. As he grew older and frail, I realized that much of his sort of understanding of the Borders would be obliterated too. Therefore I made

extensive tape recordings with my dad and in rereading the typescript of this book I can hear the echo of his insistent voice clearly. No one else can, only me.

One more word before I set out my narrative. Much to the distaste, no doubt, of proper historians this piece of work is occasionally conveyed in the first person, not objective but nominative.

In fact it is precisely names that make it so. I am a Moffat, first from western Berwickshire, earlier from Dumfriesshire. My mother’s people are Irvines, Murrays and Renwicks from Hawick and

the hill country to the west. All ancient Border families, people who stayed where they found themselves and found where they stayed to be beautiful. We have been here for millennia but, apart from

playing rugby for Scotland, none of my family has gained great wealth, fame or notoriety. We have acquired few airs or graces. There is no need. We are all Borderers, and that is more than

enough.

And that is precisely my claim. The landscape of the Scottish Border country is part of me, I know it in my soul. The red earth of Berwickshire is grained in my hands, the

rain-fed fields of the Tweed valley nourished me and the hills and forests of Selkirk fill my eye. I know this place.

2

AN ACCIDENTAL HISTORY

Since this book began its life as a series of accidental discoveries, I should begin by describing the sequence of events that forced me to draw such an unlooked-for conclusion.

Despite my frequent puzzlements and pauses I completed my history of Kelso in 1985. I remember an excellent party, some daft speeches and a hilarious dinner with my mum and dad pleased as punch that I had dedicated the book to them. Because it was the name used by ordinary people I called it Kelsae and then below it for those who wanted a Sunday name: A History of Kelso from the Earliest Times. Except it wasn’t. The earliest it got was 1113 when the future King David I of Scotland planted a settlement of austere French monks from Tiron first at Selkirk and then, moving them downriver in 1128, at Kelso. Being literate and careful men, they set down all the gifts given by David in a long foundation charter.3 While the document is rich in detail, overflows with place-names, descriptions of natural features and much monkish precision, it was none the less frustrating to have to begin the history of such an ancient place as late as 1113. Particularly since the quarry I mined for material contained nuggets of information (much of which I failed completely to understand at first) about the lost centuries before the monks of Tiron came to the Borders and wrote down what they found.

My quarry was a collection of 562 documents or charters bound together in what is known as the Kelso Liber. Published by a nineteenth-century gentlemen’s antiquarian association, the Bannatyne Club, the Liber is a singular thing. As a printing job it is remarkable as it sets out precisely the homespun, everyday Latin turned out by the monks of Kelso Abbey’s scriptorium. They wrote on precious vellum and parchment and to save space they developed an inconsistent shorthand which, maddeningly, the printers and proofreaders had reproduced in all its inconsistency. However, once I had cracked its codes I found behind the idiosyncratic Latin a terse and sometimes elegant style and, with documents dating from 1113 to 1567, a surprising continuity of expression.

The twelfth-century documents of the Kelso Liber describe important places, a busy economy, and great wealth gifted to the Church. King David I moved the Tironensian monks from his Forest of Selkirk to Kelso so that he could concentrate economic, military, administrative and spiritual power in one place. He already held a massive royal castle across the Tweed from Kelso at Roxburgh, while beside it was his royal burgh of the same name. Established as an international centre for the trade in raw wool, Roxburgh was booming in the early twelfth century. It contained four churches, a grammar school, five mintmasters and by 1150 a new town forced the expansion of the town walls to incorporate it. David I needed literate men to help him administer his kingdom; he was very often at Roxburgh and so he moved his new abbey to Kelso for convenience and strength. And for a spiritual focus to confer prestige and dignity on all around it.

The foundation charters of Kelso Abbey list a long, immensely detailed and rich inventory of property, services and hard cash given by the king and by wealthy subjects anxious to impress him. Impossible to measure in today’s values, perhaps the fabulous new wealth of the monks is best expressed by a telling comparison. By the end of the sixteenth century most, but not all, of what remained of the abbey’s patrimony was appropriated by the Kers, a notorious Border clan based at a nearby stronghold, Cessford Castle. The Kers took a new title from the old castle and burgh, then became the Innes-Kers (Ker is pronounced ‘Car’) and are now the Dukes of Roxburghe (with an ‘e’), one of the wealthiest and most widely landed families in Britain.

Twenty miles downriver was another bustling town much written about in the Kelso Liber. The port of Berwick-upon-Tweed was the main exit point and trading post for the raw wool shipped out to the primitive cloth factories of Flanders and the Rhine estuary. Colonies of Flemings and Germans were settled in the town in the early twelfth century and once again generous portions of the customs revenue, valuable property in the town, salmon fisheries in the Tweed estuary and many other rights and services were gifted by the king. These properties, incidentally, only escaped the clutches of the acquisitive Kers by dint of Richard III incorporating Berwick as part of England in 1483.

Being the supply end of an embryonic textile industry in Europe, Roxburgh and Berwick formed together the beating economic heart of medieval Scotland. When they addressed charters to their Scottish, French, Flemish and English friends, David I and his successors reflected a busy, expanding cosmopolitan society. And so long as the English and the Scots remained friends, Roxburgh, Kelso and Berwick boomed. But with the accidental death of Alexander III in 1286 and the drying up of legitimate heirs to the Scottish throne, the expansionist Edward I of England turned his attention northwards, and then followed it with his armies when he did not get his way. Centuries of intermittent border warfare ensued. Trade declined, international contact virtually ceased, and over time the Borders became a place where people crossed a frontier on their way north to do business in Edinburgh, or south to London. Berwick was split from Roxburgh, and ultimately the latter diminished to extinction.

It is easy to forget the bustle of the market place, the buzz of language – English, Scots, Gaelic, Flemish, French and German were all spoken as deals were struck in the Market Place of Roxburgh. It is all gone now, without leaving any mark on the landscape. Only the sheep are still there, quietly grazing where once their fleeces brought promissory notes of exchange from Flemish merchants.

What became increasingly clear to me as I read the Kelso Liber, all of it, was how important this place was. By any modern measure Roxburgh/Kelso was the capital place of Scotland in the twelfth century. It generated immense wealth, it minted the coinage of the young kingdom and the king set his seal on many hundreds of documents in Roxburgh Castle.

However, an important question hovered over all this. Why is this large city not noted in any source before 1113? How can it be that such an important place makes such a dramatic, instant historical appearance, like a medieval Atlantis emerging from the mists of anonymity? The truth is that Roxburgh was not built the summer before the monks arrived and sharpened their quills to write about it. Clearly the town had been established for a very long time before that. But the fact is that there are no documentary facts. Nothing to refer to except common sense and a knowledge of the place and its name.

While the consistency of expression, of grammatical form and of vocabulary over the 562 charters written between 1113 and 1567 in the Kelso Liber is remarkable, there is a quiet, barely discernible undercurrent of change which flows through that record of 450 years of experience in one place. When the Tironensians arrived in the Borders from France, they would have understood little of what local people had to say to them. As members of the French-speaking ruling élite imported into Scotland by David I, that may not have mattered much. Except in one vital area: land. Most of the abbey’s new wealth was reckoned in acreage and in order to record their gifts clearly and safely, the clerks of the scriptorium needed to know two things: the name of the place they were to own and its precise boundaries. A difficult business and the monks no doubt lost a good deal in the translation. There are nearly 2,000 place-names scattered through the documents and, even allowing for radical spelling variants, 112 do not appear on any map or in the recollection of anyone who knows the ground around Kelso. It is true that not all of the 2,000 names are located near the abbey. The monks held land as distant as Northampton, but even so 112 disappearances is surprising. The lost names are often exotic: Karnegogyl, Pranwrsete or Traverflat; but I began to see that they all shared one obscure linguistic characteristic, something that turned out to be very important to this story. Buried in the Kelso Liber is an example that explains what happened.

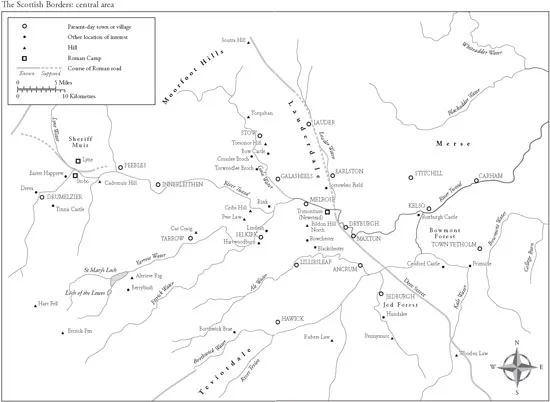

The Scottish Borders

To the south-east of Edinburgh, on the other side of Arthur’s Seat from Holyrood Palace, is the well-set suburb of Duddingston. The monks of Kelso owned part of the medieval village which they spelled as ‘Dodyngston’ in a charter which notes that it belonged to a man with an English-sounding name, Dodin. As place-names go, a simple enough derivation. But then the clerk added, for clarity, that Dodyngston used to be known as Trauerlen. This turned out to be a Welsh name which breaks into three elements: tref is a settlement or a stead, yr means ‘of’, Llin is a lake. The settlement by the lake, a place good for skating in winter. (One of Sir Henry Raeburn’s most famous portraits is of the Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch.) The first elements in the three examples of extinct toponymic exotica quoted above are also Welsh: Caer for fort, Pran for tree, and again Tref for settlement.

It became clear to me that the 112 lost names did not all disappear. Many of them were discarded as new people arrived in Scotland anxious...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of maps

- Acknowledgements

- 1 ANOTHER RIVER

- 2 AN ACCIDENTAL HISTORY

- 3 THE NAMES OF MEMORY

- 4 THE HORSEMEN

- 5 THE ENDS OF EMPIRE

- 6 AFTER ROME

- 7 THE KINGDOMS OF THE MIGHTY

- 8 PART SEEN, PART IMAGINED

- 9 THE MEN OF THE GREAT WOOD

- 10 THE GENERALS

- 11 FINDING ARTHUR

- 12 THE HORSE FORT

- 13 THE LANDS OF AIR AND DARKNESS

- Bibliography

- Index

- ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BIRLINN BY ALISTAIR MOFFAT

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Arthur and the Lost Kingdoms by Alistair Moffat in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.