- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A concise, enlightening portrait of the men who fought in the ancient battles we still study today.

Thermopylae. Marathon. Though fought 2,500 years ago in ancient Greece, the names of these battles are more familiar to many than battles fought in the last half-century. But our concept of the men who fought in these battles may be more a product of Hollywood than Greece.

Shaped by the landscape in which they fought, the warriors of ancient Greece were mainly heavy infantry. While Bronze Age Greeks fought as individuals, for personal glory, the soldiers of the classical city-states fought as hoplites, armed with long spears and large shields, in an organized formation called the phalanx.

As well as fighting among themselves, as in the notable thirty-year Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta immortalized by Thucydides, the city-states came together to fight outside threats. The Persian Wars lasted nearly half a century and saw the Greek armies come together to fend off several massive Persian forces, both on land and at sea.

This book sketches the change from heroic to hoplite warfare, and discusses the equipment and training of both the citizen soldiers of most Greek cities and the professional soldiers of Sparta.

Thermopylae. Marathon. Though fought 2,500 years ago in ancient Greece, the names of these battles are more familiar to many than battles fought in the last half-century. But our concept of the men who fought in these battles may be more a product of Hollywood than Greece.

Shaped by the landscape in which they fought, the warriors of ancient Greece were mainly heavy infantry. While Bronze Age Greeks fought as individuals, for personal glory, the soldiers of the classical city-states fought as hoplites, armed with long spears and large shields, in an organized formation called the phalanx.

As well as fighting among themselves, as in the notable thirty-year Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta immortalized by Thucydides, the city-states came together to fight outside threats. The Persian Wars lasted nearly half a century and saw the Greek armies come together to fend off several massive Persian forces, both on land and at sea.

This book sketches the change from heroic to hoplite warfare, and discusses the equipment and training of both the citizen soldiers of most Greek cities and the professional soldiers of Sparta.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Greek Warriors by Carolyn Willekes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE PERSIAN WARS

THE SERIES OF BATTLES COMMONLY KNOWN as the Persian Wars hold a central position in the western psyche. Traditionally viewed as an iconic clash between east and west they are depicted as the triumph of the independent, stubborn Greeks against Persian (foreign) tyranny and imperialism. It was a watershed moment in western history when the ‘little guy’ stood up to the ‘big guy’ and against all odds won out. One of the most common sentiments about the outcome of the Persian Wars is that the Greek victory prevented the orientalization of the west; in other words, the notion that had the Greeks lost the entire development of western civilization would have altered and our world would look rather different today. This might be a bit of an exaggeration, but we cannot discount the fact that the Persian Wars were very much a formative moment in the Hellenic world. The Persian Wars are also unique in that they were the first in western history to be recorded in a detailed manner from an investigative or empirical point of view. This is entirely thanks to an ambitious individual – Herodotus of Halicarnassus – who wrote his very significant text The Histories in the 5th century BC a few decades after the Wars. The term ‘history’ means an inquiry, and that is exactly what The Histories is – a detailed investigation into the causes of and events of the Persian War. Herodotus’ text does not simply provide a record of historical events, the author goes beyond that, analyzing events, seeking explanations and speaking with eyewitnesses to try and create a comprehensive account. On account of this, Herodotus is known as the ‘Father of History’ and The Histories is intrinsic to any study of the period.

The Ionian revolt

The Persian Wars were by no means the first contact between the Greek world and Persia. The west coast of Asia Minor (modern day Turkey) was home to a large number of Greek cities (the Ionian Greeks): Halicarnassus, the hometown of Herodotus, was one of them. These cities had been under Persian control for some time – essentially from the foundation of the Persian Empire in the 6th century BC by Cyrus the Great, the first Achaemenid king. Several of the eastern Greek Aegean islands also fell under Persian control – notably Lesbos, Chios, and Samos. Greeks inhabited these cities and islands, but they were governed by a Persian satrap and were required to pay tribute to the king. The Persians were relatively tolerant overlords. If the city paid tribute and did what was expected of it, they were essentially left to their own devices; if they did not, well, then things could get a little difficult for them. It was within these cities and islands of the Persian Empire that the seeds of conflict between Greece and Persia were planted.

The Persian Empire/Achaemenid dynasty was founded by Cyrus the Great who took the throne of a small Persian territory in 550. He subsequently conquered the territories of Media, Sardis, Lydia, Babylonia, and parts of Central Asia, laying the foundation for what would become the largest land empire known at that time. At its height the Persian Empire stretched from Egypt to the Indus. This vast expanse of territory was home to millions of people from many cultures and religions, all ruled by a single king via a centralized administration under a unified political structure.

The Greco-Persian conflict did not come out of nowhere, and though its development is due in large part to rebellion among the Greeks of Asia Minor, we cannot discount the role played by Persian imperialistic tendencies – expanding the empire west towards Greece was a logical next step. In 499, the Persians indicated this by sending a fleet against the island of Naxos, situated in the Cyclades. Control of Naxos would have given the Persians a very strategic jumping off point for further movement towards mainland Greece. Despite being caught unawares, the Naxians, were not keen to submit to Persian rule.

Although outnumbered, they stubbornly held out against their attackers for four months, at which point the Persians gave up and withdrew ‘when all the supplies they had brought on the expedition had been exhausted’ (Herodotus 5.34.2). The resiliency of the Naxians gave Persia a taste of Greek independence, a theme that will be ongoing throughout this chapter.

By choosing to withdraw their fleet from Naxos without achieving even a semblance of a victory, the Persians made themselves vulnerable as they had indicated weakness, never a good idea when trying to maintain authority over a vast and diverse empire. This provided the impetus for the beginnings of rebellion in Asia Minor, spearheaded by Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus. The exact cause of his decision is unclear, but it was likely related to the failed Persian attack on Naxos that Aristagoras had played a significant part in instigating. Regardless, Aristagoras gave up his position as tyrant and became the leader of the Ionian independence movement. Aristagoras’ inflammatory rhetoric had an immediate impact on the other Ionian cities, many of which became eager to throw off the Persian yoke.

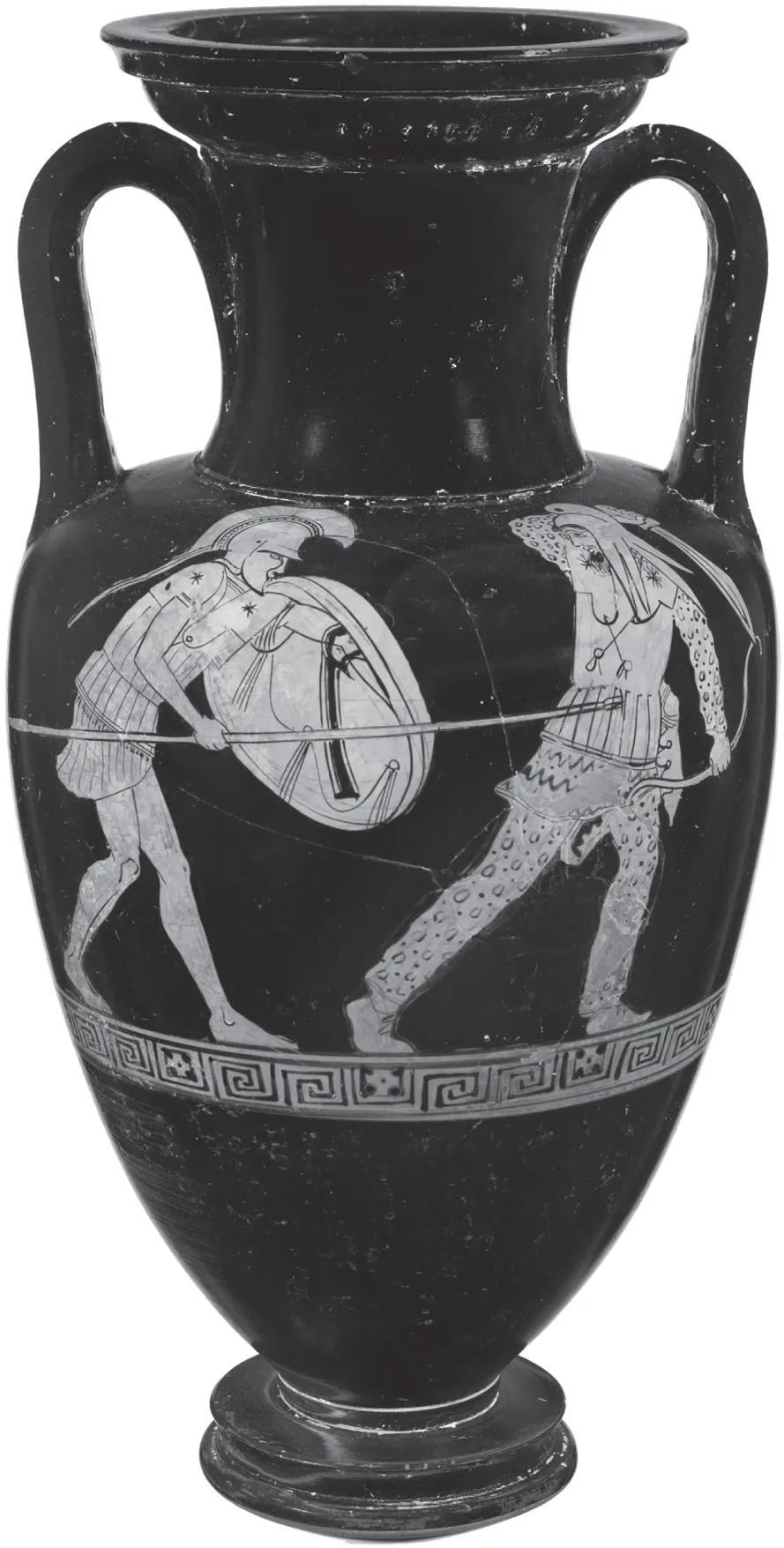

Red Figure Amphora. Battle between a Greek hoplite and a Persian archer. The Persians were renowned for their archery skills. (Metropolitan Museum of Art Open Content Program)

Despite their enthusiasm for the cause, these cities inherently understood that they could not manage this feat alone, as they were vastly outnumbered with regards to both resources and manpower. Thus, they turned to mainland Greece for help. The Ionians felt that the logical starting point was Sparta: after all, if one was going to seek military aid, why not go straight to the preeminent military power. Aristagoras made the trek to Sparta where he pitched his case for the liberation of the Ionian Greeks to king Cleomenes. It seemed that things were going in his favour and he was winning the Spartans over, until the moment when they realized where exactly Aristagoras was asking them to go.

When the day they had appointed for the answer arrived and they met at the place they had agreed upon, Cleomenes asked Aristagoras how many days the journey would take to go from the sea of the Ionians to the King. Aristagoras, though he had cleverly misled Cleomenes in everything else, stumbled at this point. For he ought not to have told him the real distance if he wanted to bring the Spartans into Asia, but instead, he told them it was a journey of three months inland. (Herodotus 5.50.1–2)

Tyranny was one of many political systems that existed in the Greek world. The term ‘tyrant’ was not considered pejorative in antiquity. Tyrants often came to power during periods of prolonged civil discord. The first generation of their rule brought stability and prosperity to city-states, often through public works programs; however, things tended to turn south with the second generation of rule as the ruler became increasingly autocratic.

Such a journey was inconceivable for the perpetually inward-looking Spartans. Fearing a Helot revolt should they travel too far from home, the Spartans sent Aristagoras packing, saying ‘My guest-friend of Miletus, you must depart from Sparta before sunset. Your request will never be accepted by the Lacedaemonians if you intend to lead them on a three-month journey away from the sea’ (Herodotus 5.50.3). Aristagoras was not yet prepared to accept this rejection: instead of departing he went to plead directly with Cleomenes at his house. Before he could present his case anew, Cleomenes’ daughter, Gorgo (who was only 8 or 9 at the time) interjected:

Father, this miserable little foreigner will ruin you completely unless you drive him out of the house pretty quick. (Plutarch Sayings of Spartan Women Gorgo.1)

Cleomenes heeded this advice and refused to speak any further with Aristagoras.

Aristagoras’ next stop was Argos, a long-standing rival of Sparta. Perhaps he hoped that they would be willing to do what the Spartans had refused simply to spite them. Unfortunately, the Argives too refused the Ionian cause. It is a strong possibility that their decision was controlled in large part by a recently received oracle from Delphi, which prophesied doom and gloom for the Argives if they became embroiled in Milesian affairs. Finally, Aristagoras made his way to Athens where he managed to secure a promise of aid from both the Athenians and the Eretrians (a large city on the island of Euboea). Why the Athenians and Eretrians agreed to support the revolt when several other major states had refused is not entirely clear. The Athenians did have a bit of a pre-existing chip on their shoulders with regards to the Persians, as they were housing the recently ousted Athenian tyrant, Hippias, who no doubt had his eye on regaining his former position with the help of the Persians. As Herodotus writes:

It was just at this juncture, when they were feeling quite antagonistic toward the Persians, that Aristagoras of Miletus arrived in Athens after his expulsion from Sparta by Cleomenes of Lacedaemon. For after Sparta, Athens was the next most powerful state. When Aristagoras appeared before the Athenian people, he repeated the same things that he had said in Sparta about the good things in Asia and about Persian warfare – that they used neither shields nor spears and how easy it would be to subdue them. In addition, he told them that Miletus was originally an Athenian colony, and therefore, since the Athenians were a great power, it was only fair and reasonable for them to offer protection to the Milesians. There was nothing he failed to promise them, since he was now in dire need, and at last he managed to win them over. (Herodotus 5.97.1–2)

As for the Eretrians, they reportedly agreed to join ‘in order to repay a debt they owed to the Milesians…’ (Herodotus 5.99.1). Yet, there must have been more to their decision. On the one hand, they clearly realized that the Persians would not look upon the Ionian revolt favourably, nor would they turn a blind eye to those who supported it. They must have, even to a minor degree, considered the fact that the Persians would eventually look west towards Greece to expand their already sizeable empire. It also appears that Aristagoras downplayed the size and strength of the Persian army, and for some reason the Athenians and Eretrians believed him, which is rather remarkable when you consider the sheer size of the Persian Empire, much of which had been gained through conquest. Nonetheless, Aristagoras’ words worked and the Athenians and Eretrians both agreed to send ships to support the Ionians, 20 and 5 respectively.

In 498 the Athenian and Eretrian ships met up with a primarily Milesian force at the Ionian city of Ephesus, from whence they marched inland to attack the provincial capital of Sardis, which ‘they captured…without resistance from anyone whatsoever’ (Herodotus 5.100.1). The satrap of Sardis, Artaphernes, was caught entirely unawares but managed to hold off his attackers by maintaining control of the acropolis, which he defended with a large force. The arrival of Persian reinforcements placed the invaders in a vulnerable position, and so they made a hasty retreat to Ephesus having accomplished very little other than burning a portion of the city and angering the Persians. The retreating Greek force was overtaken just outside of Ephesus and suffered heavy losses. The surviving Athenian and Eretrians limped home with news of their defeat and the realization that the Persian army described by Aristagoras and the Persian army in reality were two very different things. They washed their hands of the situation ‘and although Aristagoras sent many messengers with appeals to the Athenians, they refused to help the Ionians any further’ (Herodotus 5.103.1).

The involvement of these two Greek cities in the attack on Sardis did not go unnoticed by the Persian king, Darius I. He vowed to strike back, indeed ‘he appointed one of his attendants to repeat to him three times whenever dinner was served: “My lord, remember the Athenians”’ (Herodotus 5.105.2).

For the moment he was forced to be patient in his desire for revenge due to the ongoing actions of the Ionians who, despite the debacle at Sardis, were not prepared to give up. Instead they moved to spread the rebellion north towards the Hellespont and south to Caria. At the same time, they offered support to the island of Cyprus, which had rebelled against Persia. Darius was forced to focus his attention on quashing the rebellions in Asia Minor and the Eastern Aegean islands, which he did efficiently and systematically. Finally, in 494 he was able to focus on the heart of the rebellion – Miletus. By this point the Milesians had tired of Aristagoras, but his death in battle against the Thracians left the Milesians at a bit of a loss with regards to how they should proceed. Along with their remaining allies, they made a determined effort to resist the Persian assault on their city, but the absence of unified leadership led to the desertion of several allies and their ships, leaving Miletus without a fleet to protect it. Meanwhile, the Persians were taking advantage of the vast network of resources available to them to besiege Miletus. Bit by bit all of the cities and islands that had joined in Aristagoras’ rebellion were subdued and punished harshly, particularly Miletus. According to Herodotus the fall of Miletus had been predicted by the oracle at Delphi, but in a strange turn of events, the prophecy was not uttered to Milesian envoys, but rather to an Argive group: the same oracle that prophesied trouble for Argos should they involve themselves with Miletus also gave a second response:

The time will come, Milesians, devisers of evil deeds,

When many will feast on you: a splendid gift for them;

Your wives will wash the feet of many long-haired men,

And others will assume the care of my own temple at Didyma (Herodotus 6.19.2)

The oracle’s predictions proved true: the temple of Apollo at Didyma fell to the Persians and the Milesian women found themselves enslaved to ‘long-haired men’– the Persians. With the Ionian revolt brought to a close, Darius could now turn his attention farther west, looking beyond the Cycladic islands to mainland Greece. In 492 Darius made his move by appointing his relative, Mardonius, commander of the Ionian region and sending him into Thrace and along the northern Aegean towards Macedonia to begin paving the way for a Persian invasion of Greece.

The battle of Marathon

Things really kicked off in 491 when Darius sent envoys to several major Greek cities demanding they submit to Persian authority by giving him the symbolic gifts of earth and water.

Darius’ demands received mixed responses: all the island states capitulated as did several on the mainland (they ‘medized’– joined the Medes/Persians), but others reacted with anger. The Athenians in particular went so far as to throw the envoys into a well. Their excessive reaction to the envoy’s request may have been connected to the ongoing presence of Hippias in Persia. With his demands soundly rejected by the Athenians, on whom he had sworn vengeance, Darius called up an army, which was made up of levies from across the Persian Empire and prepared to sail for Greece under the command of Datis, while Darius himself remained in Persia. The purpose of this expedition does not appear to have been a large-scale conquest, but rather to secure a foothold in eastern Greece, which the Persians could use as a base for campaigns further inland. It also had the underlying purpose of punishing the Eretrians and Athenians for their role in the Ionian revolt. The Persian fleet did not make a beeline for the mainland, but sailed via several of the islands, starting with Naxos, all of which submitted, thereby securing a supply line across the Aegean between Persia and Greece. From there the Persian fleet made for Eretrian territory on Euboea. The Eretrians, realising that they were outnumbered:

…had no intention of marching out to meet them in battle, so now their prevailing plan was to stay in the city, and their main concern was to defend its walls if they possibly could. The assault on the walls was fierce and lasted for six days, and many fell on both sides. On the seventh day, two prominent citizens, Euphorbus son of Alcimachus and Philagrus son of Cyneas, betrayed their city and surrendered it to the Persians. After entering the city, the Persians plundered and set fire to the sanctuaries, exacting vengeance for the sanctuaries burned down in Sardis, and as Darius had instructed, they enslaved the people. (Herodotus 6.101.2–3).

The Persian fleet then turned their attention towards Athenians and their homeland of Attica. On the advice of Hippias, they made for the plain of Marathon, a place that provided ideal terrain for the Persians as it would allow them to make use of both their larger numbers as well as their cavalry, the bulwark of the Persian army.

The Athenians had not remained idle. They had gathered...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Timeline

- Chapter 1: The Persian Wars

- Chapter 2: The Peloponnesian War

- Chapter 3: The Rise of Macedonia: Philip II and Alexander the Great

- Sources

- Acknowledgements