eBook - ePub

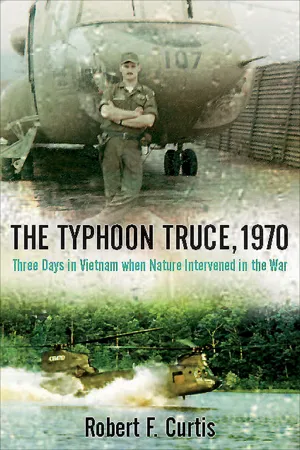

The Typhoon Truce, 1970

Three Days in Vietnam when Nature Intervened in the War

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This military history chronicles a time during the Vietnam War when fighting stopped and the 101st Airborne helped those in need during a natural disaster.

For three days during the Vietnam War, it wasn't rockets or artillery that came through the skies, but a horrific force of nature that suddenly put both sides in awe. When Super Typhoon Joan arrived in October 1970, an unofficial truce began. Air crewman faced masses of Vietnamese civilians outside their base perimeters for the first time. Could we trust them not to shoot? Could they trust us not to drop them off in a detention camp? Truces never last, but while they do, life changes for everyone involved.

The "typhoon truce" stopped the war for three days in northern I Corps—that area bordering the demilitarized zone separating South Vietnam from North. Then, less than a week later, Super Typhoon Kate hit the same area with renewed fury. As the entire countryside was flooded, the people faced war and natural disaster at the same time.

No one but the Americans had the resources to help the people who lived in the lowlands, and so they did. The everyday dangers they faced were only magnified by low clouds and poor visibility. But the aircrews of the 101st Airborne went out to help anyway. In this book, we see how, for a brief period during an otherwise vicious war, saving life took precedence over bloody conflict.

For three days during the Vietnam War, it wasn't rockets or artillery that came through the skies, but a horrific force of nature that suddenly put both sides in awe. When Super Typhoon Joan arrived in October 1970, an unofficial truce began. Air crewman faced masses of Vietnamese civilians outside their base perimeters for the first time. Could we trust them not to shoot? Could they trust us not to drop them off in a detention camp? Truces never last, but while they do, life changes for everyone involved.

The "typhoon truce" stopped the war for three days in northern I Corps—that area bordering the demilitarized zone separating South Vietnam from North. Then, less than a week later, Super Typhoon Kate hit the same area with renewed fury. As the entire countryside was flooded, the people faced war and natural disaster at the same time.

No one but the Americans had the resources to help the people who lived in the lowlands, and so they did. The everyday dangers they faced were only magnified by low clouds and poor visibility. But the aircrews of the 101st Airborne went out to help anyway. In this book, we see how, for a brief period during an otherwise vicious war, saving life took precedence over bloody conflict.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE MEN OF PLAYTEX AND LIFE IN VIETNAM

WALKING FISH

“A fish just walked across the sidewalk in front of me,” the tall, thin young man in the green flight suit and darker green rain jacket said as he came through the door of Playtex’s Officers’ Club. The three men already there, all pilots, just laughed and shook their heads in disbelief. A walking fish, really …

C Company, 159th Assault Support Helicopter Battalion (ASHB), 101st Aviation Group, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), was given the call sign “Playtex” in 1969, prior to leaving the United States for Vietnam. Their official motto was “Support Extraordinaire,” but naturally, given the name Playtex, their unofficial motto became, “We give living support,” echoing the women’s underwear company’s slogan. When C Company returned to the States after the war, the call sign was immediately changed from “Playtex” to the more politically correct “Haulmark.” Political correctness had not yet been invented in 1969, so they were Playtex. None of the pilots or enlisted men in this story knew how or why the call sign Playtex came to be, nor were they curious enough to find out.

At any given moment, there were between 35 and 45 officers assigned to Playtex, all of them aviators. Of those, perhaps 30 would be available for flying at any one time. The rest had just arrived, were checking out, were sick, lame, or lazy or were on R&R (rest and recuperation) in Australia or Taiwan or Thailand if they were single, or in Hawaii if they were married. There were 200 to 250 enlisted men and, like the officers, maybe 20% were off somewhere else and not available for duty. For the first month or so after you joined Playtex, you were a “newbie,” as in New Boy, whether you were a commissioned officer, a warrant officer, or an enlisted man. Second tour soldiers were not newbies; they already knew how to behave.

The oldest officer in Playtex was usually the CO (Commanding Officer), most often a major, but captains filled the job on occasion. The CO at the time when the floods came that October was a short, slim African American and the best commander many of the officers would ever have. He was the best because he trusted his officers to do their jobs, left them to do those jobs, and as long as they did their jobs properly, ran interference for them with the “higher ups” when necessary.

Early in his stint as CO of Playtex, the major called a formation of all the officers. When he spoke he said, “I am commanding officer of this company, but I’m not a Chinook pilot. I have been a Huey pilot for years, and truth be known, I prefer them to Chinooks. Chinooks are just too damn big and ugly. Yes, I had the Chinook transition course, but I really don’t know that much about our mission and, as CO, I don’t have time to learn. So here’s what’s going to happen; I am going to let the experts, you all, do the missions. I know you will do them well. When I fly, I will fly as a co-pilot and you can be sure I will be flying with the most experienced pilots, so that I don’t screw things up too much. Meanwhile, I will handle the paperwork and keep higher headquarters off your collective asses. Company dismissed!”

And he did as he promised: the warrant officers flew the missions and never heard a word from above about anything. They would all miss the major when he left.

The pilots themselves came in two varieties: commissioned officers and warrant officers. The difference between the two was primarily education. Commissioned officers, in theory, had a college degree, or at least some college. They were expected to be more capable of handling all facets of military life, including administration. To the warrant officers they were all “RLOs,”—“Real Live Officers.” Warrants, on the other hand, only required a high school diploma, or its equivalent, a General Education Development (GED) certificate. Warrants were expected to be technicians, highly skilled in one thing, in this case flying. Since commissioned officers always out rank warrants, the most junior 2nd lieutenant out ranked the most senior warrant officer. Socially, warrants and commissioned officers mostly stayed with their own groups, as did the enlisted men. It was much easier that way because you didn’t have to remember who you had to call “Sir,” instead of just calling them by their name.

The CO was probably between 35 and 40 years old, but that was really old compared to the warrant officers, who made up nearly all the rest of the pilots. The average age of Playtex’s warrants was probably 21. The oldest of the warrants, CW2 Marvin Leonard, was 35 and considered a sage, due to his advanced years and vast experience. There were three captains: the Executive Officer (XO), the Operations Officer, and the Maintenance Officer. Below the captains, there were four 1st lieutenants, mostly holding down “assistant” jobs—assistant maintenance officer, assistant admin officer, etc. There were a few 2nd lieutenants too, but they were all warrants who had taken what was commonly called a “Penny Postcard” commission.

The Army was so desperate for officers in 1970 that any warrant could send in a request to the Department of the Army for a commission. If you had been a warrant for more than a year, you got a 1st Lieutenant’s (1LT) silver bar in the return mail. If less than a year, a 2nd Lieutenant’s (2LT) gold bar. The primary reason a warrant would take a Penny Postcard Commission was that it cut an entire year off the time owed to the Army. Take a warrant and you owed the Army three years. Take a commission and you only owed two, clearly showing the Army’s view of the relative value of the two types of officers. Early release from service was something nearly everyone wanted in 1970, as witnessed by the acronym “US ARMY” on the patch over every soldier’s left jungle fatigue pocket. All the soldiers considered it an abbreviation for “Uncle Sam Ain’t Released Me Yet.” Promotions came so fast in 1970 that it was nearly impossible for a commissioned officer to make it to Vietnam as an aviator and still be a 2nd lieutenant, since there was only a year between a gold bar and a silver bar. The schooling required to become an officer in Army Flight School took longer than it took to be promoted.

Playtex’s warrant officers themselves came in two varieties: Warrant Officer 1 (WO1 or “Wobbly One”), the most junior rank, and Chief Warrant Officer 2 (CW2). A CW2 was someone who had been a warrant for over a year and had not screwed up badly enough to be passed over for promotion. It took a lot to screw up that badly and yet not get court-martialed. In the Army somewhere were also CW3s and CW4s, the oldest, most senior of the warrant officers, but there were none of these in Playtex. To graduate from Army Flight School and receive your warrant, you had to be at least 19 years old. If your grades had been good at Fort Rucker, Alabama, you might be offered Chinook transition, which took another six weeks, meaning you could be in Vietnam flying combat missions as an Aircraft Commander (AC) before you turned 20.

THE TECHNICIANS

The warrants flew the vast majority of Playtex’s missions, rightly so, since they were the aviation technicians and, theoretically at least, the most qualified. It was a brilliant move on the Army’s part, using warrant officers, men barely out of their teens, as the primary combat pilots in Vietnam. Their vision and reflexes were as good as they ever would be. Twenty-year-olds do not, as a rule, have a highly defined fear sense, particularly a fear of death. Death is something that happens to other people, not to them. Unlike the RLOs, they generally did not have four years of college behind them; instead they had an Olds 442, a Pontiac GTO, or a Chevy Chevelle SS396 in the parking lot back home, and car payments that came close to equaling their pay. They usually didn’t have obligations beyond these car payments, i.e. no wife and kids back in the States. Most of all, they could fly eight to twelve hours a day, day after day, month after month, for a year. Their bodies were not yet too worn for such abuse, nor were their minds, but they would be if they survived, particularly if they survived two one-year tours. And here, in Vietnam, the Army gave these young men multi-million dollar high performance machines and sent them out with minimal supervision, a boy’s second dream. Everyone knows what a boy’s first dream is.

Referring to that first boy’s dream, Playtex’s base was named “Liftmaster Pad,” sometimes informally called “Titty City” by the men of Playtex. It was actually a mini-airfield with a short runway suitable for lining up helicopters for takeoff on missions in the morning, a small control tower mounted on telephone poles where a single, bored air traffic controller worked, large tents for maintaining the aircraft, and steel parking revetments to hold the company’s 16 Chinooks. On first viewing, the whole base at Liftmaster Pad was ugly: raw shacks on the sandy dirt with a scraggly banana tree here and there, but after a while you didn’t see the ugly any more. It just was normal, not ugly at all. And that was how the war was, too—ugly at first, but after a while it was just normal.

Our story takes place in I Corps, the northern most part of what was then South Vietnam. Liftmaster Pad was on the edge of the coastal lowlands at Phu Bai, just a few miles south of Vietnam’s old imperial capital, Hue City. A few miles to the west were the mountains where the fire support bases, the one’s that Playtex supplied with ammunition for their howitzers and food and water for the men, were located. Liftmaster was located away from the rest of the 159th Assault Support Helicopter Battalion (ASHB). The other two Chinook companies, the “Pachyderms” and the “Varsity,” as well as the Battalion Headquarters, were about a mile away from Liftmaster, next to the main runway at the Phu Bai airport. Liftmaster was out at the edge of the big American base clustered around that airport, close to the barbed wire and bunkers that protected the northwestern outer perimeter of the base. The men of Playtex liked it that way; being as far from headquarters as possible meant that they escaped a lot of “Army” things that went with being around senior RLOs, like saluting and wearing proper uniforms. Over on Phu Bai main, it was considered improper to walk through the company area naked to get to the showers, but no one at Liftmaster even noticed such things.

Of course, Playtex was not as far away from headquarters as the fourth company in the 159th ASHB, a CH-54 heavy lift helicopter company, call sign “The Hurricanes.” They were 50 miles away from the rest of the battalion, at China Beach, down in the southern part of I Corps at Da Nang, down where the “round-eyed” American nurses, three big PXs, and Air Force Officers’ Club at Da Nang airport were. On weekends there would be local lovelies outside the gate and discrete meetings might be arranged, between fancy dinners at the Air Force Clubs. None of those things were available at Phu Bai or Liftmaster, only the raw earth and buildings already starting to rot in the ever-damp air.

LIFTMASTER

If you arrived by helicopter at Liftmaster Pad, you would find yourself on the flight line, a short PSP (pierced steel planking, rectangular sheets of steel that lock together to make a temporary road or runway) runway, with steel revetments on one side and the company street on the other. As mentioned earlier, the revetments were steel walls about eight feet high and a foot wide, spaced far enough apart that you could easily taxi a Chinook between them. Liftmaster had 16 of them, one for each Chinook assigned to Playtex. Their purpose was to protect the aircraft from rocket and mortar blasts and shrapnel.

When you walked out of the flight line through the gate in the perimeter barbed wire by the tower and crossed the street, you were looking at the company headquarters and S-1 (admin offices). If you looked back, you would see a homemade sign hanging on the wire advertising Chinooks for sale at “Honest Mel’s Used Hook Lot,” an attempt at humor by two of the warrants. Once you were across the street, if you turned left at the Playtex sign, you would be looking at Playtex’s outdoor theater where movies were shown most nights, the exception being, of course, when it rained. Someone built a shack at the back of the theater to house the projector and added a white-painted plywood screen at the front.

Anyone watching a movie had better use a lot of bug repellent, since lots of mosquitoes lived at Liftmaster, too. Some of them carried malaria, which is why there was a big bowl of pills by the mess hall entrance door. Monday through Saturday it was full of white pills and on Sunday, a larger red pill. The pills didn’t prevent malaria, but they supposedly suppressed its symptoms. Who knows what they would do to the users when they were older. Like Agent Orange in Vietnam and atomic radiation in the 1950’s, the U.S. military didn’t pay too much attention to such things at the time. One immediate side effect of the pills was a mild case of diarrhea that lasted as long as you took them.

The seats at the outdoor theater were benches made from Chinook rotor blades—ones too shot up or otherwise damaged to be sent back to the depot to be repaired. One of them had a distinct dent about a foot from the end, deep enough to have damaged the rotor blade’s spar, rendering it effectively destroyed. Once, while one of Playtex’s Chinooks was dropping off a sling load in a saddle on an Army of Vietnam (ARVN) fire support base (FSB) in the mountains, an inattentive soldier walked down the side of the saddle near, very near, to where the helicopter was setting down its load. As he walked down the hillside, he apparently wasn’t paying attention to the hovering Chinook; instead, he was shielding his eyes from the dirt its rotor wash was blowing up. In doing so he walked head first into the spinning aft rotor blades. His head disappeared instantly in a red spray, his body rolling on down to the bottom of the hill, blood spurting out as it tumbled.

Normally, this would not have done much, if any, damage to the rotor blade since human heads are relatively soft, but this ARVN soldier had his steel helmet on, and the impact badly dented the blade, even damaging the spar. The aircraft commander (AC) saw that the dead soldier’s comrades weren’t taking the accident well and, since they were all holding loaded rifles, rather than waiting to see what they would do next, he released the sling load immediately and flew away in the now badly vibrating helicopter. He landed at the next base about five miles away, and shut the aircraft down to see how much damage had been done. Too much, so maintenance came out and changed the blade, and since it was too damaged to repair, it became a bench in the theater. Whatever red had been on it was long since gone.

If you turned right at the Playtex sign and walked up the sidewalk, you would pass the operations bunker and the S-4 (supply) office. It was easy to tell which one was the operations bunker because it was the only building with sandbags around it. The sandbags had deteriorated now, ripped in places with weeds sprouting in the gaps. The S-4 was easily identifiable too, since it had a sign out front that read in big letters, “C Co Supply” with smaller letters underneath that announced modestly, “Support Extraordinaire,” C Company’s official motto. Behind the two offices was the enlisted living area. Continue on straight past the S-4, and you would come to the officer’s living area.

Playtex’s living area, both officer and enlisted was, of course, set out in an orderly, military fashion. All the buildings, except the ammo storage building, were SEA (Southeast Asia) huts, “hootches” to the men who lived in them. They were all one story, made of plywood, about 20 feet wide by 50 feet long, with tin roofs. The roofs all had been reinforced with sandbags on each side, connected with communications wire to help keep the tin panels in place during high winds. None of the SEA huts, enlisted or officer, were sandbagged on the sides to protect against incoming mortar or rocket.

This is not to say that there was no protection against “incoming.” There were sandbagged bunkers here and there between some of the hootches—basically half culverts with sandbags piled around them—for the men of Playtex to shelter in when the mortars and rockets started to fall, but the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) rarely bothered to shell Phu Bai. They would have to move through too much open land between the forest and the perimeter of the base for them to get within range for their rocket launchers or mortars. They would be spotted by the Americans well before they could get their weapons set up. Both sides knew full well that “what can be seen can be killed,” and with the American artillery covering nearly all of I Corps, and Cobra gunships that could be in the air within minutes of being scrambled, the NVA knew they would have been pounded by one or both within minutes of being seen. So, the NVA didn’t often bother with Liftmaster Pad.

Where there were no bunkers between the SEA huts, there were clotheslines. Rather than count on the Vietnamese laundry, many of the men hand washed their own clothes in the sinks by the common showers. When it was dry outside the clotheslines would be full of once-white tee-shirts, green shorts and socks, green flight suits, and green jungle fatigues, all flapping in the wind like the flags of the member nations outside the UN.

The SEA huts were put up by the Seabees (Navy Construction Battalions) in one furious rush, two years before our story begins. For some unknown reason, all the hootches were painted light blue, but the paint rapidly faded as the wood warped in the heat and humidity, leaving the walls mottled. The larger enlisted billeting area was close to the flight line, behind the company headquarters and other offices. All the enlisted hootches, except for the ones occupied by the senior non-commissioned officers (NCO), were split into two sections by a partition down the middle. Four enlisted men lived on each side. The sergeant major had his own half of one SEA hut, more space than any of the officers, except the CO.

Walk on to the right past the enlisted area and the theater, and you came to the officer’s hootches. The officer’s area was separate, surrounded by a privacy fence about five feet high made out of sheets of roofing tin. When the rains came that fall, Playtex’s officer housing area felt it, too. Although built on land slightly higher than the enlisted area, water still stood everywhere in the officer’s courtyard. The horseshoe pit was under water, as was the area around the stone barbeque grill, because after the first week of rain, the ground, pure sand or not, was too saturated to absorb more water.

The sandbagged bunkers between the rows of hootches were full of water too, not that it mattered, since hardly anyone used them. Even when the pilots,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Prologue: Rain Unending

- Chapter One: The Men of Playtex and Life in Vietnam

- Chapter Two: The 159th, the Aircraft, and the Mission

- Chapter Three: October 14, 1970

- Chapter Four: October 16, 1970

- Chapter Five: October 17, 1970

- Chapter Six: October 18, 1970

- Chapter Seven: October 24, 1970

- Chapter Eight: October 25, 1970

- Chapter Nine: October 26, 1970

- Chapter Ten: October 27, 1970

- Chapter Eleven: Typhoon Joan Arrives and the Typhoon Truce Begins

- Chapter Twelve: October 28, 1970

- Chapter Thirteen: October 29, 1970

- Chapter Fourteen: October 30, 1970

- Chapter Fifteen: October 31, 1970—the Aftermath

- Epilogue: They Still Live

- Appendix: Who They Were

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Typhoon Truce, 1970 by Robert F. Curtis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.