- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Way of the Eagle

About this book

A classic aviation memoir: an American pilot's account of air combat in the First World War.

Charles J. Biddle, a Philadelphia native, was active in France beginning in 1917, where he flew as a volunteer, initially for the French in Escadrille 73, and then in the American 103rd Aero Squadron, the Lafayette Escadrille, and then the 13th Aero Squadron and 4th Pursuit Group, which he commanded.

His memoir was published shortly after his return to the United States and provides an immediacy lacking in other books that were written later. Accounts of US pilots from this period are relatively rare, and this one paints a compelling picture of a group of Americans fighting as volunteers for the French. Biddle's US compatriots soon established their own capability and wrung free of French direction—and as this book reveals, it was largely because of their combat prowess.

For his service, Biddle was awarded the French Legion of Honour, the Croix de Guerre, the American Distinguished Service Cross, and the Belgian Order of Leopold II. This memoir gives us a unique perspective on America's participation in the Great War.

Charles J. Biddle, a Philadelphia native, was active in France beginning in 1917, where he flew as a volunteer, initially for the French in Escadrille 73, and then in the American 103rd Aero Squadron, the Lafayette Escadrille, and then the 13th Aero Squadron and 4th Pursuit Group, which he commanded.

His memoir was published shortly after his return to the United States and provides an immediacy lacking in other books that were written later. Accounts of US pilots from this period are relatively rare, and this one paints a compelling picture of a group of Americans fighting as volunteers for the French. Biddle's US compatriots soon established their own capability and wrung free of French direction—and as this book reveals, it was largely because of their combat prowess.

For his service, Biddle was awarded the French Legion of Honour, the Croix de Guerre, the American Distinguished Service Cross, and the Belgian Order of Leopold II. This memoir gives us a unique perspective on America's participation in the Great War.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Way of the Eagle by Charles J. Biddle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

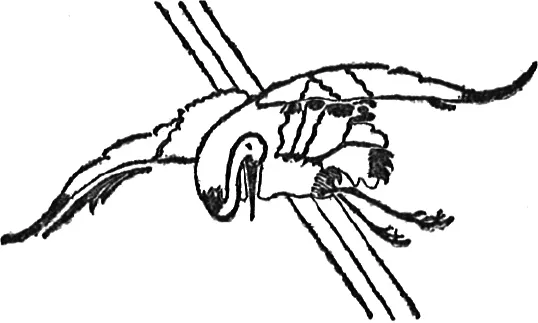

ESCADRILLE N. 73

INSIGNIA OF ESCADRILLE N. 73

BERGUES. July 28, 1917.

Just arrived at the front today and am in Escadrille N. 73, Groupe de Combat 12. The group is otherwise known as “Le Groupe Brocard” after its famous commander Brocard, who is one of the great French airmen. One of the escadrilles of the group is N. 3, more generally known as “Les Cigognes” or “The Storks” when translated into English. The name comes from their insignia, a stork painted on the sides of the fuselage* of each machine, and this squadron is easily the best known in the French aviation. The whole group carries the stork as its insignia, the bird being placed in different positions to distinguish the several escadrilles, and consequently the entire group is often referred to as “Les Cigognes.” The original “Cigognes,” however, which has gained such a wide reputation, is Escadrille N. 3.

This group is the most famous fighting one in the army and admittedly the best, so you can ee that Chadwick and I were very lucky to get in it. It contains more famous fighting pilots than any of the other French flying units, one in particular Guynemer, who has to date brought down about 48 Boches officially and many more unofficially. To count on a man’s record, a victory has to be seen and reported by two French observers on the ground or some such rule as this, so that a Boche shot down far behind the lines where no one but his comrades see him fall, does not help a pilot’s total. Last evening Guynemer got one 25 kilometres in the German territory and as I sit here on the aerodrome he has just gotten into his machine and started off for the lines in search of another victim.

Chadwick and I and two other Americans who came with us, are the first Americans to be sent to this group. An escadrille or squadron in the French service numbers about fifteen pilots and machines. We are indeed fortunate to get in this crack group, but as it has suffered rather heavily lately, they had to fill up, and so we got our chance. This morning the captain of one of the escadrilles* was killed and our own chief† was shot down with three bullets in his back but will pull through all right. He was shot down last night also, but only his machine was damaged. He went up again this morning and while attacking one Boche, another got him from behind. He has 17 Boches to his credit officially, so I guess he is entitled to the rest that his wounds will give him. The captain who was killed had gotten seven German machines officially, so we are sort of out of luck to-day, losing two such good men. It seems to come in bunches that way for some reason or other.

It looks as though I shall see lots of service and have a chance to learn a great deal before the time comes to transfer to the U. S. Army, if it does come. We hope to be able to stay where we are for a considerable length of time and that we shall not be forced to leave this French unit before we have learned a lot more about military aviation and have been able to make some return for all the training that we have received. This group is usually, like the Foreign Legion, moved about to the particular locality in which there is going to be an attack, so we shall see plenty of action. It was for instance at the battles of Verdun and the Somme and it seems that it is usually in the thick of it. For this reason it is obvious that I shall not be able to tell you where I am and must be very careful what I write. Since beginning this letter I have been talking to one of the officers about the censorship and have, as you will notice, been doing some censoring on my own account. No details that could possibly be of any military importance, so you will have to be content with much briefer and more general letters than I have been writing heretofore.

You will be glad to know that I got a S.P.A.D.* machine, the kind I hoped to get. Also I shall have a chance to do a good deal more practising before starting in in earnest. The officers are as usual very nice and willing to help in any way they can. We get a great deal of advice and information here which I have been anxious to get from the beginning. When the time comes to make our first trip in search of a real live Boche, we ought to feel able to give him some sort of a run for his money. Here’s hoping that my first adversary is a young pilot like myself. Should hate to bump into a German ace for a starter.

BERGUES, July 29, 1917.

Guynemer came back from his sortie last night having sent one more Boche to his happy hunting grounds in flames. This wonderful French pilot seems absolutely untiring and his skill must be something uncanny. Approximately 50 Boche officially means about 75 machines brought down altogether, and as most of his victims have been two-seaters, this represents I suppose something like 125 German pilots and machine gunners, observers, etc., disposed of by one Frenchman. You can imagine how much nerve, skill and endurance it takes to accomplish this feat and live to tell the tale. I was much surprised when I saw him for the first time. He is small and very slight, more like cousin T—— than anyone else I can think of whom we know, indeed he looks something like him. He is 22 years old and without question the greatest individual fighter this war has produced. There are many things about him which I should like to tell you but which I am at present forbidden to talk about and which will therefore have to wait until later on when they are still interesting but no longer of military importance.

It is quite a sight to see a bunch of the “Storks” starting off at crack of dawn for a flight over the lines, or to see them coming home to roost at dusk. One sees here probably the finest flying in the world and it will be a great advantage to us young ones, who as yet are not real pilots by a long shot, to be able to watch these men work who really know the game. One is naturally anxious to get started, but I shall take your advice and go easy until I feel able to take care of myself. As you say, rashness only results in throwing yourself away to no purpose and foolhardiness is certainly no essential of bravery. As far as one can discover, the most successful men have been those who have known when not to sail in and take too great chances.

BERGUES, July 30, 1917.

Our machines have not yet arrived and we shall probably have to wait some little time longer, so Chadwick and I have as yet done no flying since reaching the front. There is however plenty to do in the way of studying so the time does not hang heavily on our hands. There are maps of the locality to learn, types of Boche machines to familiarize oneself with and all kinds of things like this to keep one fully occupied. It is however irritating to be so near the scene of action and yet so far. When I was in the schools I used to think that I would wish I was back home again when the time came to go out over the lines. Maybe I still shall feel that way and my present enthusiasm is merely due to my excessive greenness. Just now, however, with the big guns roaring all day and all night in the distance and all of our companions in the fray except a few of us new ones who have no machines as yet, it makes you wish you could go out and get in it. The guns sound like distant thunder. We are too far away to hear any but the big ones, but the explosions remind me more than anything else of the noise made by the paddle wheels of a steamer on the river on a quiet evening. You know how they sound in the distance as each blade hits the water. The noise of the guns has of course no such regular time as the sound of the paddle wheels, but the shots are I should say, considerably closer together than the blows of the paddles on the water. Remember that this represents only the big guns and that we are too far away to hear the 75’s at all, and you will get some idea of how much fun the Boches are having at the other end where the projectiles are falling on their blessed heads.

We are very comfortably housed here in a big tent and “everything in the garden is lovely” except the mosquitoes, which are quite numerous and at least three times the size of Jersey’s best. They are the first I have struck so far in France, but they are making up for lost time. They are honestly half as big as what we call a mosquito hawk and have a beak like a great blue heron. The first one I saw I mistook for one. One bit me on the right eye-lid the first night and I could hardly get my eye open in the morning. Then another one, who evidently saw me and had his eye for symmetry shocked by the sight, bit me on the other eye-lid the next night, so that yesterday my eyes about matched. Last night I fooled them by sleeping with my head under the covers and to-day my visage does not quite so nearly resemble the morning after a prize-fight.

A funny thing happened here a couple of days ago while some of the men were practising bomb dropping at a target on the flying field. The Spad can be fitted to carry a couple of small twenty-pound bombs which are dropped from a low altitude on troops and convoys on the roads behind the enemy lines. The bombs in question were filled simply with a small bursting charge and some stuff that would make a smoke, so that the aviator could see where they fell. One fellow let one go from about 3500 feet, but he had waited too long and it landed on a road within six feet of an English “Tommy” who was taking a quiet stroll. If it had ever hit him it would have pushed him out of sight. Everybody thought it a huge joke except the “Tommy,” who was bored to death (or almost) and could not see anything funny about it. It is amusing to note the difference in the popular attitude towards such an episode, here and at home. With us the result would probably have been a law suit and a long argument on the legal theory of injury resulting from fright alone without physical contact.

You will be glad to hear that my commander, Commandant Brocard, seems from what little I have seen of him, to be the finest French officer I have yet met. He is a real man himself and takes that personal interest in the welfare and ability of his men, which means so much. It is quite evident that he means his men to know their business thoroughly before he sends them out.

I think Aunt K—— might like this place. My tent is in a field next to some farm buildings and the pasture is full of horses, cows, and three or four big fat sows. The latter are very inquisitive and every now and then try to come in and pay us a visit, but a heavy army shoe, well placed in the spare ribs, generally results in indignant grunts and a hasty withdrawal. We came in one day to find them all asleep in our tent. One old lady had her head in my suitcase where I keep my clean linen. She had first pushed open the lid and eaten a supply of chocolate I had secreted there. My laundry bill the following week amounted to twelve francs. We also have a large supply of dogs who travel with us. Five fat puppies run about the kitchen-dining-room tent and lick the plates and pots and pans. One is called “Spad” and another “Contact,” the latter being the French expression meaning “throw on the switch of a motor.” The other names I have not yet mastered.

At each advance in my training the food has improved until here it is first rate. As for my health, it has never been better, and my spirits are excellent. The work is interesting and I try to make it a rule to do little thinking about what I might be doing if it were not for this damn war. Do not worry if my letters are irregular as the censorship is now severe and will, I fear, subject the mails to long delays.

BERGUES, August 10, 1917.

Have at last had a couple of flights over the lines and will try to tell you something about it, but in such general terms that the censor will not object. After almost incessant rain, fog, and very low clouds for ten days, it has finally cleared up enough in the last two days to allow the machines to go out for at least a part of each day. Yesterday morning I had my first trip out over the Boche lines and as the patrol of which I was a part, was quite a low one, I could see the whole show and you never saw such a mess in your life. At times we were as low as 800 metres and on our way home went down to 600 metres over the artillery where we could plainly see and hear the guns blazing away. Higher up, one can see the gun flashes, but the noise of one’s motor drowns the sound of the shots.

I do not think there is much use in trying to describe what the battlefields look like. They beggar description, and you can get a clearer idea from the pictures in the “Illustrated London News.” The ground about the trenches and in fact the country for several miles on each side of the lines, reminds me more of some of those swamps which had been burnt over by a forest fire, which we saw on the way in to the Rangeley Lakes in Maine, than anything else I can think of. I know nothing else which gives an idea of the utter waste and destruction. The ground itself looks much like one of those hard lumps you sometimes find on the river shore which resemble a petrified sponge, or perhaps a piece of slag from an iron foundry, or again a photograph of the craters on the moon. For miles the shell holes are so close that they merge, and the earth is chewed up until the surface also somewhat resembles the top of a bowl of stiff oatmeal. Every little village and farm house is a wreck, the roofs, where any are left, are full of shell holes; but a few fragments of walls represent what is left of most of them. Some of the larger towns are just a dark smudge with a gutted ruin sticking up here and there.

This morning I went out on a patrol at daylight, a couple of thousand metres up this time, and the sight which greeted us as we approached the lines I shall never forget. It was much more remarkable than yesterday from a spectacular point of view. The sun was not yet up and the flashes from the guns, which you can see even in broad daylight, were very brilliant in the early dawn. There was quite a lively bombardment going on and the guns made me think of the fireflies on the lawn at home of a hot summer night, and I might say that I have never seen the fireflies thicker. This from our guns behind our own lines and the Boche fireflies at work further on but not so numerous. Over it all the drifting smoke of the battle and above, all the way from 1000 to 5000 metres, flocks of planes circling about. Scattered about the planes the little puffs of smoke from the shells of the anti-aircraft guns of each side shooting at the other fellows’ birds. Some kilometres behind the lines on each side a row of sausages, as the observation balloons are called, floating lazily at the ends of their long tethers. Add to this the sun rising on one side and the moon and a couple of big stars fading out on the other, and you may get some kind of a picture of what we see here every day.

It is a funny sensation to sail around up in the air and watch the shells bursting around you. If they are anywhere near, which they generally are if they are meant for you, the noise of the explosion is very clear and there is always the puff of smoke to show you what kind of a shot the man on the ground is. Bang, bang, they go, sometimes over, sometimes under where you hear them but they are hard to see, at the sides, behind or any old place. Don’t get the idea that we are surrounded by a swarm of shells however. As you pass near a battery they may let go two or three, the next time perhaps a dozen and so on from time to time. We flew about over a given sector of Boche territory for pretty nearly two hours yesterday and something over an hour to-day, acting as guards for the bigger machines which take the pictures, regulate the artillery fire, etc. Expect to go out again later on to-day if the weather permits, which I doubt.

The Boche gunners are pretty good when you consider the terrific speed of the machines and that they were shooting at a range of two miles. The closest that any came to me that I saw was about 150 yards, but that is close enough to suit yours truly. Had to laugh at Chadwick when we came in yesterday. He said that when he saw the first shell that he knew was meant for him, he felt quite flattered to think that the Boche should have at last taken that much notice that he was in the war and “agin” them. As for me, when we are dodging around up there in the sky to throw the guns off their range, I feel like a blooming duck on the first day of the open season, and there are many other forms of flattery which I should prefer. Chadwick hates a Boche even more than I do and I think that is going pretty strong. The more one sees of them and of their work the more convinced one becomes that they are not simply a nation misled, but a very race of devils.

BERGUES, August 12, 1917.

On my first trip out over the lines, some Boche machine gunner or rifleman on the ground amused himself by plugging a bullet through one of my wings. Considering that we were never under 800 metres on this sortie, that Fritzie must be a regular Robin Hood. Probably it was just a lucky shot but I’ll bet that fellow used to shoot ducks before the war. A bullet hole through the cloth of a wing practically does no harm at all, and the mechanics just glue a little patch over it when you come home. You can find these patches on the majority of the machines.

Since writing the first part of this letter I have had four or five more hours over the lines. This morning I was down as low as five hundred metres over our own trenches and got a wonderful view of everything. It is a beautiful cl...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- In the Schools

- Escadrille N. 73

- Escadrille Lafayette

- 13th Aero Squadron, A. E. F.

- 4th Pursuit Group, A. E. F.