eBook - ePub

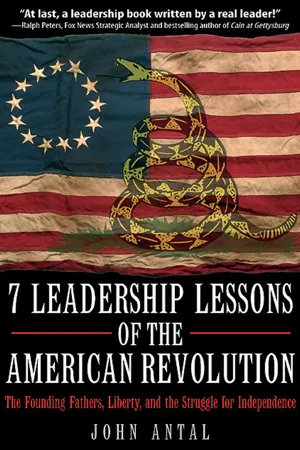

7 Leadership Lessons of the American Revolution

The Founding Fathers, Liberty, and the Struggle for Independence

- 241 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

7 Leadership Lessons of the American Revolution

The Founding Fathers, Liberty, and the Struggle for Independence

About this book

"A leadership book written by a real leader! . . . eminently useful for those 'in command' of organizations of any kind. A stimulating five-star work" (Ralph Peters,

New York Times–bestselling author).

This book tells the dramatic story of seven defining leadership moments from the American Revolution, as well as providing case studies that can improve your leadership at home, business, in your community, in the military, or in government.

Leadership is not about position, it is about influence. You can be a leader no matter what your rank or position. It is not about power, it is about selflessness. You cannot be a good leader unless you can also be a good follower. Good leaders don't shine, they reflect. Lessons like these are the core of this book. The stories in this book are about leaders who were challenged at all corners, adapted, improvised and overcame. The tales of leaders like Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, Henry Knox, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington, to name a few, are stories you will want to know and tell. These leaders knew how to push teams to succeed under the toughest conditions. These stories will come alive on the pages of this book to fuel your leadership fire and make you a better leader in any endeavor. Learn how they secured our liberty so you can transform today into a better tomorrow.

"John Antal has captured seven timeless stories that will raise your leadership awareness and make you a better leader in peace or war, at home, at work or in your community." —Steven Pressfield, bestselling author of 36 Righteous Men

This book tells the dramatic story of seven defining leadership moments from the American Revolution, as well as providing case studies that can improve your leadership at home, business, in your community, in the military, or in government.

Leadership is not about position, it is about influence. You can be a leader no matter what your rank or position. It is not about power, it is about selflessness. You cannot be a good leader unless you can also be a good follower. Good leaders don't shine, they reflect. Lessons like these are the core of this book. The stories in this book are about leaders who were challenged at all corners, adapted, improvised and overcame. The tales of leaders like Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, Henry Knox, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington, to name a few, are stories you will want to know and tell. These leaders knew how to push teams to succeed under the toughest conditions. These stories will come alive on the pages of this book to fuel your leadership fire and make you a better leader in any endeavor. Learn how they secured our liberty so you can transform today into a better tomorrow.

"John Antal has captured seven timeless stories that will raise your leadership awareness and make you a better leader in peace or war, at home, at work or in your community." —Steven Pressfield, bestselling author of 36 Righteous Men

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 7 Leadership Lessons of the American Revolution by John Antal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE FIRST TEA PARTY

The Leadership of Samuel Adams

If our trade be taxed, why not our lands, in short, everything we posses? They tax us without having legal representation!

—SAMUEL ADAMS

No taxation without representation.

—MOTTO OF THE SONS OF LIBERTY

LEADERSHIP IS THE ART OF INFLUENCE.

In 1770 two regiments of British soldiers occupied Boston. On a clear and cold winter night on March 5th, an angry mob of colonists heckled a guard outside the Custom House on King Street. A squad of British soldiers soon reinforced the sentry. As the squad stood their ground, boys threw snowballs and oyster shells at the Redcoats. The soldiers shouted at the boys and more citizens of Boston assembled to join the commotion. The crowd grew. Many in the crowd exchanged insults with the British and taunted them to fire. The boys continued to throw snowballs and icicles. A boy got too close and a soldier struck the boy in the head with the butt of his musket. The angry crowd surged forward shouting and cursing as the British soldiers came to arms. Suddenly, a British soldier was knocked down, his musket discharged, and in the confusion the rest of the Redcoats fired a volley into the throng of angry civilians. When the smoke cleared, five Boston men lay dead on the snowy street.

The incident was quickly dubbed the Boston Massacre. Patriot Paul Revere created an etching of the event that depicted the British firing line mercilessly blasting away at the crowd of unarmed citizens. Nineteen-year-old Henry Knox, a local bookstore owner, was there at the scene of the shooting and vowed that the Redcoats would hang for the murder of innocent citizens. The newspapers carried the story to every colony in America. The cry rang out, near and far, that the British Regiments had to leave Boston.

After the killings, over three thousand citizens of Boston and the surrounding villages gathered in and around the Old South Church to demonstrate their resentment at the British occupation. The size of the crowd was not lost on Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who was charged with keeping order in the king’s colony. The last thing the governor wanted was to resort to force.

Samuel Adams, a member of the Massachusetts Legislature, carried the people’s petition to an audience with the Governor. The petition demanded that the British troops leave Boston. Hutchinson and Adams were bitter enemies. Adams was the leader and organizer of the patriot group called the “Sons of Liberty,” a major thorn in Hutchinson’s side. Adams’s Sons of Liberty opposed the Crown’s intolerable policies that regulated the colonies and taxed their industry. The Sons of Liberty showed their disdain for British rule by hanging effigies of royal officials from the “Liberty Tree,” a tall elm tree that stood in the Boston Commons. Over the years the tree became a rallying point for protests against the Crown. The Sons of Liberty also threw stones at royalist homes, and even tarred and feathered tax collectors. In general, Adams and his rowdy rabble were the governor’s nemesis and, now that blood had been shed, an angry force that must be carefully reckoned with.

Demonstrating the power of his office, Hutchinson sat serenely in a large chair, flanked by members of his staff, facing the assembly of disgruntled patriots. Hutchinson calmly gazed at the rabble-rouser who was causing him so much trouble: Samuel Adams. The two men could not be more different. Adams wore a very plain set of clothes and a coat that looked as if it had been slept in. Dressed in his finest clothes, Hutchinson expected to diffuse the situation with a demonstration of his authority by granting an audience with Adams. He hoped that this would boost the man’s ego and be enough to calm the mob. From his commanding position in the assembly hall the Governor looked at Adams and tried hard not to sneer.

To Adams, the governor’s chair looked like a throne, a throne that stood for an abusive and unaccountable government that Adams had grown to despise. Next to the Governor sat a British army officer, a lieutenant colonel resplendent in his immaculate red uniform, who represented the military power behind the throne. The officer commanded the British soldiers garrisoning Boston and was responsible for the men who had fired on the crowd. Instead of being impressed or overawed, Adams saw Hutchinson on the defensive.

Without hesitation, Adams stepped boldly forward, arms folded across his chest, and addressed Hutchinson. He looked the governor firmly in the eyes and insisted that all British troops be withdrawn immediately. Adams knew that he had the people on his side and most of the population of Boston was outside the building and filled the streets. Adams wanted Hutchinson to realize that he was resolute and that the people would not be deterred. “I am in fashion and out of fashion, as the whim goes. I will stand alone,” Adams announced with defiance. “I will oppose this tyranny at the threshold, though the fabric of liberty fall, and I perish in its ruins!”

The crowd supported Adams with applause and shouts. The noise of the crowd echoed from outside. Governor Hutchinson sensed that the meeting was going poorly and he feared the citizens of Boston might riot. He tried to compromise with the drably dressed firebrand standing in front of him by offering to remove one regiment, leaving the other in place. “If you have the power to remove one regiment, you have the power to remove both,” Adams countered, his gray eyes flashing as he pressed his point. “It is at your peril if you refuse. The meeting is composed of three thousand people. They have become impatient. A thousand men are already arrived from the neighborhood, and the whole country is in motion. Night is approaching. An immediate answer is expected. Both regiments or none.”

Hutchinson’s face paled. Adams smiled as he saw the governor’s knees twitch. After a moment of silence the governor nodded, looked away and then, in a sullen voice, agreed that both regiments would leave Boston the following day.

Later, when an ardent British supporter in the Massachusetts Legislature asked Governor Hutchinson why he had not tried to sweeten Samuel Adams’s disposition by offering him a paid position in the governor’s office, an office from which he could exert control over Adams, he replied: “Such is the obstinacy and inflexible disposition of the man, that he never would be conciliated by any office whatever.”

Samuel Adams was not a man to be trifled with. An agitator for liberty, he was not a contented man. Contented men do not lead rebellions. In most governments, and especially in the thirteen British colonies in America, fomenting a rebellion was a crime punishable by death.

Long before the Boston Massacre and the meeting with Governor Hutchinson, Samuel Adams had attended the prestigious Boston Latin School and graduated from Harvard College, paying his way by waiting on tables in a restaurant. He tried his hand at brewing beer, failed in business, and went on to earn a masters degree. His thesis foretold his future: “Whether it be lawful to resist the supreme magistrate if the commonwealth cannot otherwise be reserved.” In January 1748 Adams started a newspaper, the Independent Advertiser. The paper was entirely about politics and very critical of the king’s policies in the Thirteen Colonies. Adams was acting editor and wrote most of the material. The paper’s theme was consistent: Massachusetts or any other free society should govern itself. Many of the ideas in Adams’s articles were based on the theories of John Locke (1632–1704), an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers, who wrote extensively on the rights of common man and liberty. Locke wrote that government is morally obliged to serve people by protecting life, liberty, and property. Armed with Locke’s Enlightenment ideas, Adams became devoted to politics and spent most of his time discussing opposition to British rule. Although the Independent Advertiser failed as a business, Adams had found his calling.

In 1764 Adams vigorously opposed the Sugar Act, a tax imposed by Parliament on sugar. He was elected to the Massachusetts legislature in 1765 and was reelected annually to the legislature until 1775 when the American Revolution broke out and the legislature was dissolved. His passion for liberty drove him to oppose the British government at every turn. He believed it folly to hope for reconciliation and compromise with the king’s officials, particularly with the royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson.

Adams believed that Great Britain’s administration over its American colonists was arrogant, heavy-handed, and unjust and should be ended. In his eyes Great Britain had betrayed existing laws and had broken its political compact with the colonists, a compact that had promised a system of limited government and noninterference by the Crown in internal colonial affairs. By 1773 many Americans were angry with the British for a series of intolerable laws and decrees, but few called for open rebellion or armed revolution. For most, Great Britain was still their country, King George their sovereign and revolution the farthest thing from their minds. Many hoped that the British Parliament would listen to the colonists’ grievances and change the laws to fit the character and special circumstances of the American colonies.

Adams believed that there was never a right time for dramatic change. Years of studying politics caused him to believe that only a combination of vigorous leadership and dramatic action could bring about change. He was determined to supply both the vigorous leadership and the dramatic action.

His greatest strengths lay in his passion for Liberty and his ability to communicate his passion to others. He was also a skillful leader and organizer. He was not the finest orator in the colonies, but he could write clearly and became one of the preeminent journalists in America. He used his talent for writing and his classical and religious education to report on the important issues of the day. He was an ardent proponent of a free press and had a nose for news. He was not rich, in fact he was habitually poor, but he was extremely skilled in inspiring and motivating people. Significantly, he had an uncanny ability to understand the needs, wants, and dreams of his fellow colonists. He wrote “mankind is governed more by their feelings than by reason.” He was one of the first investigative journalists to use his understanding of emotions to great political advantage.

Passion was Samuel Adams’s most powerful attribute. When charged with passion, his penetrating gray eyes could animate anyone caught in his gaze. Embittered by what he considered inconsiderate and arrogant British rule, he leveraged his passion to fuel his effort to organize networks of like-minded patriots. He then linked the networks so they could operate with unified purpose. He called these networks “committees of correspondence.” The correspondence generated by these committees, in the form of pamphlets and newspapers, spread information about American dissatisfaction with British rule. Adams went one-step further by declaring to the committees that if the British imposed taxes without the consent of the colonists, it would lead to rebellion.

The correspondence circulated in Massachusetts and throughout the Thirteen Colonies via the remarkable postal service created by Benjamin Franklin, the first postmaster in the colonies. Franklin was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, joint postmaster general of the colonies for the Crown in 1753, and postmaster for the United Colonies in 1775. His organizational genius created one of the most efficient and rapid postal services in the eighteenth century. The postal routes he instituted moved correspondence hundreds of miles throughout all the colonies in days rather than weeks. Samuel Adams and his committees of correspondence took advantage of this excellent communication system to fan the fires of dissatisfaction against the Crown.

One of the principal networks Samuel Adams helped organize in 1765 was a group called the Loyal Nine. The Loyal Nine agitated against the British Stamp Act. As this group grew in numbers it became known as the Sons of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty met to oppose the Coercive Acts and heavy-handed British Rule. They met under an old elm in Boston that Adams named The Liberty Tree. It became a rallying site for patriots. Some of the more famous Sons of Liberty were Patrick Henry, John Hancock, James Otis, Paul Revere, and Dr. Joseph Warren. The Massachusetts governor suspected the Sons of Liberty of plotting to overthrow the government, but the Sons insisted that they were standing up for their rights as British subjects and had the right as British subjects to protest unjust laws. Sons of Liberty groups soon sprouted in each of the colonies and many royal governors feared them, for many of these men were also members of the colonial militias. As the Crown tightened its grip through regulation and taxation, the Sons of Liberty adopted the motto: “Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

Taking action, the Sons of Liberty and other like-minded organizations agitated against the royal governors and harassed and intimidated British tax collectors. Unwelcome in nearly all American communities, tax collectors, Stamp Act officials, and other Crown officials were easy targets for the practice of tar-and-feathering. Samuel Adams led the effort to boycott British goods and deny the tax collectors revenue. As the actions of the Massachusetts colonists grew into open rebellion with the Crown, King George III decided to teach the unruly Americans a lesson.

On May 10, 1773, a new Tea Act was authorized by Parliament. It allowed the British East India Company to import half a million pounds of tea into the colonies without paying tax, duties, and tariffs. The foremost objective of the Tea Act was to establish the supremacy of Parliament to levy taxes on the American colonies. Its secondary purpose was to support the troubled British East India Company that had tea it was unable to sell. This privileged status gave the nearly bankrupt British East India Company a monopoly to sell tea directly to its own agents in the colonies who had a surplus of tea that needed a market. With this monopoly the British East India Company could disrupt the established supply chain for tea. They could legally bypass the established colonial middlemen, undercut the price of smuggled Dutch tea into the colonies, and undersell American merchants. With cheap British tea shipped directly to agents favored by the Crown, American businessmen involved in the tea trade were out of a job. All across the colonies, Colonial merchants were furious about the Tea Act.

The act levied only a three-penny tax per pound on tea arriving in the colonies. The cost was paid by the British agent and passed on to the customer, but the tea was still cheaper than smuggled tea. The money generated by the tax, however, went directly into the royal coffers to pay for British officials living in America, thereby making these officials dependent on the Crown for their livelihood and independent of colonial control. Previous to this, colonial officials were paid by local taxes and were beholding to the local citizenry. This gave the Crown tighter control over the leaders of the colonies. The Tea Act therefore, was less about taxing tea to raise income for the British government than in proving the Crown’s right to arbitrarily raise taxes on Americans.

Many colonists felt that their rights as Englishmen were being usurped. The Tea Act angered Americans all across the Thirteen Colonies and each colony found its own way to oppose it. The ports of Philadelphia and New York City refused to let British ships laden with tea unload their cargoes and turned the ships back in protest. In Boston, however, the royal governor of Massachusetts allowed the tea ships to dock and ordered that the tea be unloaded and the taxes paid.

Governor Hutchinson had several good reasons to support the tea tax. First, he was a loyal British official who always obeyed the king and Parliament; he was demonstrating his loyalty to his superiors. Second, he had invested substantially in the East India Company and would profit nicely when the tea were unloaded and sold in Massachusetts. Third, his two sons and his son-in-law were three of only five people who were licensed to handle shipping and sales for the East India Company in Boston and their fortunes were tied up in the sale of this tea.

Samuel Adam...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Other Book

- Dedication

- PREFACE: Leadership, Liberty, and the American Revolution

- 1 THE FIRST TEA PARTY: The Leadership of Samuel Adams

- 2 IF WE WISH TO BE FREE: The Oratory of Patrick Henry

- 3 A BOSTON BOOKSELLER: The Accomplishments of Henry Knox

- 4 OUR LIVES, OUR FORTUNES, AND OUR SACRED HONOR: The Collaboration of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson

- 5 VICTORY OR DEATH!: Washington at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton

- 6 CHARGE BAYONETS!: Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens

- 7 THE GREAT DUTY I OWE MY COUNTRY: Washington at Newburgh, New York, 1783.

- 8 EXCEPTIONALISM, LIBERTY, AND LEADERSHIP

- APPENDIX A: Common Sense by Thomas Paine

- APPENDIX B: The Declaration of Independence

- APPENDIX C: The Crisis, December 23, 1776 by Thomas Paine

- APPENDIX D: A Transcript of General George Washington’s Letter to Congress on the Victory at Trenton

- APPENDIX E: A Transcript of General George Washington’s Report to Congress on the Victory at Princeton

- APPENDIX F: General Washington’s Speech to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh, New York

- APPENDIX G: Timeline of the War for Independence

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- About The Author