- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Vikings at War

About this book

An illustrated guide to Viking warfare from strategy and weapons to culture and tradition: "a very excellent introduction to the Viking age as a whole" (Justin Pollard, historical consultant for the Amazon television series

Vikings).

From the time when sailing was first introduced to Scandinavia, Vikings reached virtually every corner of Europe and even America with their raids and conquests. Wherever Viking ships roamed, enormous suffering followed in their wake, but the encounters between cultures also brought immense change to both European and Nordic societies.

In Vikings at War, historian Kim Hjardar presents a comprehensive overview of Viking weapons technology, military traditions and tactics, offensive and defensive strategies, fortifications, ships, and command structure. The most crucial element of the Viking's success was their strategy of arriving by sea, attacking with great force, and withdrawing quickly. In their militarized society, honor was everything, and ruining one's posthumous reputation was considered worse than death itself.

Vikings at War features more than 380 color illustrations, including beautiful reconstruction drawings, maps, cross-section drawings of ships, line-drawings of fortifications, battle plan reconstructions, and photos of surviving artifacts, including weapons and jewelry. Winner of Norway's Saga Prize, Vikings at War is now available in English with this new translation.

"A magnificent piece of work [that] I'd recommend to anyone with an interest in the Viking period." —Justin Pollard, historical consultant for the Amazon television series Vikings

From the time when sailing was first introduced to Scandinavia, Vikings reached virtually every corner of Europe and even America with their raids and conquests. Wherever Viking ships roamed, enormous suffering followed in their wake, but the encounters between cultures also brought immense change to both European and Nordic societies.

In Vikings at War, historian Kim Hjardar presents a comprehensive overview of Viking weapons technology, military traditions and tactics, offensive and defensive strategies, fortifications, ships, and command structure. The most crucial element of the Viking's success was their strategy of arriving by sea, attacking with great force, and withdrawing quickly. In their militarized society, honor was everything, and ruining one's posthumous reputation was considered worse than death itself.

Vikings at War features more than 380 color illustrations, including beautiful reconstruction drawings, maps, cross-section drawings of ships, line-drawings of fortifications, battle plan reconstructions, and photos of surviving artifacts, including weapons and jewelry. Winner of Norway's Saga Prize, Vikings at War is now available in English with this new translation.

"A magnificent piece of work [that] I'd recommend to anyone with an interest in the Viking period." —Justin Pollard, historical consultant for the Amazon television series Vikings

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. THE VIKINGS

Who were the Vikings?

In the early 9th century, Scandinavia did not yet have nations with well-defined borders. Politically, the region consisted of a number of petty kingdoms connected by various military and political alliances. What united the peoples was their common culture, language and belief system.

S candinavia was not isolated, however. Scandinavians had close trading links and contact with other northern European populations. In fact, they had set fashion trends for the English and French nobility at the end of the 8th century. The royal court of Northumbria adopted Scandinavian fashions in dress and in hairstyle. There had been trade and communication between Scandinavia and the rest of Europe for centuries, however Viking raids were the first direct experience that a French or English farmer would have of Scandinavia, which he would have previously considered only as a vague and unknown world.

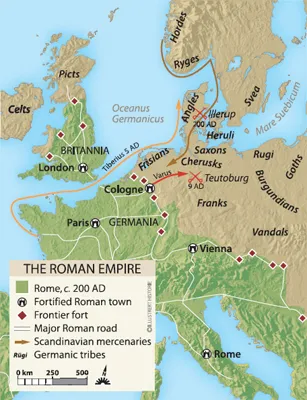

Nor was waging war in distant lands a new phenomenon for the Scandinavians. The Scandinavian peoples were able to mobilise large armies and make war both between and beyond their own territories, even before Viking times. In the first few centuries AD, clear power structures already existed and Scandinavian leaders were able to wage war on a scale previously unknown to them. They learned military strategy and technology from the Romans. After a major defeat by the Germans at Teutoburg Forest (in modern-day Germany) in 7 AD, the Roman Empire had established a permanent northern border along the Rhine. German and Celtic mercenaries already made up a large part of the Roman standing army at that time, and chieftains’ sons from the whole of northern Europe received military and cultural education from the Romans. Roman luxury goods and weapons and military skills spread north. These military skills also reached Scandinavia, mainly through the Nordic mercenaries who fought as support troops alongside the Roman legions. This is confirmed by the finding, especially in Denmark, of large quantities of Roman weapons and equipment. Weapons and knowledge were also acquired by trade and through the many alliances and connections between powerful tribal leaders in Scandinavia and tribes further south.

Partly as a consequence of this new military technology, a powerful military aristocracy evolved in Scandinavia during the 3rd century AD. This had its origins in the military leaders of the Germanic tribes, who were called kings. From then until the 6th century, increasing militarisation of the tribal societies and widespread warfare led to the collective tribal institutions being replaced by a system of petty kings who dominated different geographic areas, supported by local chieftains.

Finds of elegant weapons and equipment dating from the centuries before the Viking Age indicate that powerful rulers dwelt in Scandinavia. This 7th-century helmet was found in a boat burial in Vendel in Uppland, Sweden.

After the battle the warriors’ equipment was cast as offerings into a lake in modern-day Illerup on Jutland. The warriors who fell here were probably on their way home to west Norway after the end of their service in the Roman army. The finds confirm the close contacts that existed between Scandinavia and the Roman Empire in the centuries before the Viking Age.

A glimpse of the earlier warrior culture

In c. 200 AD, an army from Norway lost a big battle, not far from Illerup on Jutland in Denmark. All the warriors’ personal equipment and weapons were ritually destroyed and cast as offerings into a nearby lake. Weapons belonging to about 750 ordinary soldiers, 100 soldiers from the middle ranks and 12 officers were found. The warriors were well equipped, with elegant Roman weapons but also with more homely things such as antler combs and working tools. They had been well paid, for their purses were full of Roman denarii. If we estimate that the Norwegian losses were around 50% (which corresponds to a serious defeat), the total force could have been around 1,700 men, about the size of a Roman auxiliary troop. The Norsemen may have been on their way home to western Norway after serving in the Roman army. We know the names of some of those who took part in the fateful expedition, because they had carved their names in runes on their belongings: Wagnijo (Wayfarer), Nithigo, Gauthi, Laguthewa, and Swarta (The Black).

During this period a series of defensive works was raised and major building programmes initiated for military purposes, such as roads, bridges, canals and earthworks. The extraction and use of iron continued to increase in importance, and possession of weapons became more usual among the lower classes. In the course of the 7th and 8th centuries there was further professionalisation of the military forces. All this was happening at a time when Scandinavia was experiencing a period of relative peace.

When was the Viking Age?

The Viking Age is part of the period which Scandinavian archaeologists call the Nordic Late Iron Age (600–1050 AD)

This period is further divided into sub-groups which sometimes overlap. The time before the Viking Age is known in Scandinavia as the Vendel Age (550–800), after the rich finds from Vendel in Sweden, or the Merovingian Age (482–751), after the dynasty of French kings who ruled France from the fall of the Roman Empire until the Carolingians came to power in 751. The Nordic Late Iron Age was followed by what Scandinavian archaeologists call the Middle Ages (1050–1500). The Viking Age comes between the Vendel Age and the Middle Ages.

According to our definition, the Viking Age is mainly a period when people in Scandinavia were heathen, not yet Christianised, and when Nordic chieftains and kings engaged in widespread plundering and warfare both at home and throughout Europe.

The timespan of the Viking Age can be defined in various ways. The most usual is to say that it started with the attack on the monastery on the island of Lindisfarne in England on 8th June 793. Among other things, this is well documented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where English monks wrote their annual reports. The event is also named in several letters written by churchmen. It is clear that this attack shook the church institutions in England, and it has continued since then to be regarded as the event which initiated the Viking Age. However, there are reports of earlier Viking attacks on England. In the introduction, we have already described the killing of Beaduheard and his men in 789. In 792 King Offa, who ruled the English kingdom of Mercia from 757 to 796, organised coastal defences, almost certainly in response to increased Viking pirate activity. We must also consider that many raids were never recorded in writing.

This definition is useful to mark the beginning of the Viking period in England, but an event outside Scandinavia is not well suited to define a Scandinavian epoch. We should look within Scandinavia for other events: we shall consider technological innovations such as the development of sail and increased iron production from the 750s, combined with social and political factors. The same applies to the end of the period which in many cases is defined by the defeat of Harald Hardråde in England in 1066.

The population of Scandinavia gradually converted to Christianity over the course of the Viking Age, and it is reckoned that more or less all of Scandinavia, with the exception of the region of Uppsala in Sweden, had been converted by the middle of the 11th century. The change in religion cannot however be used to define the transition from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages. Many of the leading Vikings – Kings Olav Tryggvason, Canute the Great and Olav Haraldsson (St Olav), to name but a few – were more or less Christian.

In the Middle Ages the Scandinavian countries emerged as independent kingdoms, but the process of nation building was in progress both during and after the Viking Age, and was almost complete in Denmark long before 1100, in Norway sometime after 1100 and in Sweden not before 1200. So neither the change in religion nor the political development of the Nordic countries into statehood can be used to define the end of the Viking Age.

The arrival of the Vikings

787 (789). In this year Beorhtric took King Offa’s daughter Eadburh (as wife). And in his time there came for the first time three ships with Norsemen from Hordaland. And the bailiff rode to them to bid them appear in the king’s town, because he didn’t know who they were. So they killed him. These were the first ships of Danes that came to the English folk’s land.1

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Peterborough manuscript)

The end of the period cannot be linked to any particular event or societal change, but to many different processes and events: the gradual cessation of plundering raids and invasions from Scandinavia; a break in the stream of immigration to the Islands in the West (Orkney, Shetland, Faeroes, the Hebrides and Iceland) and to England and France; the increasing power of the church over the everyday life of the people; and the increase of royal control by means of military power, law, trade and not least, worldly goods. Looking at all these elements together, we can say that the Viking Age as we understand it was over by the year 1100, though it can be argued that the Viking Age continued later in some places. In the 13th century, people could still be found worshipping the old Norse gods in some parts of Sweden. Caithness in Scotland and the Islands in the West were ruled by Norse earls and chieftains who continued summer plundering forays until the 14th century. However, we choose 1100 as the year when the Viking age ended, and this book will use a time frame of 750–1100 for the Viking Age.

What does ‘Viking’ mean?

The word ‘Viking’ immediately evokes a familiar image: warriors with helmets, shields and axes; traders sailing to England in their longships; or the adventurous settlers fearlessly crossing the sea to Iceland. But ‘Viking’ was an ambiguous description when used either by the Scandinavians themselves or by others. In France they were called Norsemen or Danes. In England they were all labelled as Danes or heathens. In the East they were referred to as Rus or Varangians, but in Muslim Spain they were called al-madjus (fire-raisers) or Norsemen. No distinction was made between Norwegians, Swedes and Danes such as we have today.

Only in Ireland, where the common expression heathens was also used, do we gradually find traces of a differentiation between Norwegian and Danish Vikings. The Norwegians were called Finn Gall and the Danes Dub Gall. Opinions differ about the origin of these terms, but Finn Gall can be interpreted as either ‘the white foreigners’ or ‘the old foreigners’ and Dub Gall as either ‘the dark foreigners’ or ‘the new foreigners’.

The expression ‘Viking’ was used at that time, but not as a description of a race of people. The word is found in sources in both England and Scandinavia, but there are several theories about the etymological origin of the word and what it really means, and no source has confirmed where it originated geographically.

‘Viking’ is found in contemporary sources such as runic inscriptions on stones, in skaldic lays, and in European narratives and chronicles. The first time the expression appears in a literary context is probably in the Anglo-Saxon poem, Beowulf, which may date from the middle of the 8th century. The words wigendra/wigend and wigfrecan appear and are both interpreted as ‘warrior’.

The word ‘Viking’ as we know it appears for the first time in Anglo-Saxon sources. In The Exeter Book from the 9th century we find a reproduction of a poem, Widsith, which may be from the 6th or 7th century. A part of the poem refers to tribes or groups and chiefs who apparently are Scandinavian.

What were the Vikings called?

In what are now Germany and France the Vikings were called nordmanni, nortmanni or askomanni. In England they were described as dani and northman, and in Ireland as gall or lochlannach. In Spain they were called lordemaõ, madjus, al-madjus or al-magus. In Russia and Byzantium they went by the names of rus, væring, varæger or varjager. In Byzantium they were also called skytere.

Among them are Vikings (line 60) and Sami (line 80). The unknown author of the heroic poem describes a journey through Europe at the time of the tribal migrations in the 5th and 6th centuries:

I was with the Wenlas, Waernes and Wicingas

I was with the Gefthan, Winedas and Gefflegan

I was with the Angles, Swaefe and Aenanas

I was with the Saxons, Sycgans and Sweordweras.

‘Wicingas’ may be the name of a particular tribe, but it is more likely to be either a professional description, for example ‘sea warrior’, or a description of a place of origin, such as Viken, the land around the inlet of the Oslo Fjord.

When the word ‘Viking’ appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 878 (879) the meaning is more apparent. Here, it is probably an expression for ‘sea pirate’ or ‘plunderer’. We can deduce this because the Scandinavian warriors of the large army which was operating in England at the same time, ‘the Great Heathen Army’, are referred to as Danes. Had all Scandinavian warrior bands been called Vikings at that time, the chronicle would surely also have referred to the warriors in the army as Vikings.

Perhaps the best explanation of the meaning of the word comes from Scandinavian sources. The designation ‘Viking’ is found on many rune stones,2 both in a masculine form (vikingr), which is translated as ‘sea-warrior’, and in a feminine form (viking) as ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- FOREWORD

- BEADUHEARD MEETS HIS FATE

- 1. THE VIKINGS

- 2. THE ART OF WAR

- 3. VIKING FORTIFICATIONS

- 4. VIKING SHIPS

- 5. VIKING WEAPONS

- 6. VIKING INVASIONS

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- LIST OF MAPS

- IMAGE CREDITS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vikings at War by Kim Hjardar,Vegard Vike in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.