- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A detailed chronicle—including eyewitness accounts—of the year American Patriots turned the tables on the British in the US War of Independence.

In 1781, the future of America hung by a thread. British troops occupied key coastal cities, from New York to Savannah. After several harsh winters, the American army was fast approaching the breaking point. Mutinies began to emerge in George Washington's ranks, and it was only the arrival of French troops that provided a ray of hope for the American cause.

1781 was a year of battles, from the Patriot victory in the Battle of Cowpens, to Gen. Nathaniel Greene's impressive Southern campaign. In the Siege of Yorktown, the French fleet, the British fleet, Greene, Washington, and the French army under Rochambeau all converged in a fateful battle that would end with Cornwallis's surrender on October 19.

In this book, Robert Tonsetic provides a detailed analysis of the key battles and campaigns of 1781, supported by numerous eyewitness accounts, from privates to generals in the American, French, and British armies. He also describes the diplomatic efforts underway in Europe during 1781, as well as the Continental Congress's actions to resolve the immense financial, supply, and personnel problems involved in maintaining an effective fighting army in the field.

In 1781, the future of America hung by a thread. British troops occupied key coastal cities, from New York to Savannah. After several harsh winters, the American army was fast approaching the breaking point. Mutinies began to emerge in George Washington's ranks, and it was only the arrival of French troops that provided a ray of hope for the American cause.

1781 was a year of battles, from the Patriot victory in the Battle of Cowpens, to Gen. Nathaniel Greene's impressive Southern campaign. In the Siege of Yorktown, the French fleet, the British fleet, Greene, Washington, and the French army under Rochambeau all converged in a fateful battle that would end with Cornwallis's surrender on October 19.

In this book, Robert Tonsetic provides a detailed analysis of the key battles and campaigns of 1781, supported by numerous eyewitness accounts, from privates to generals in the American, French, and British armies. He also describes the diplomatic efforts underway in Europe during 1781, as well as the Continental Congress's actions to resolve the immense financial, supply, and personnel problems involved in maintaining an effective fighting army in the field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 1781 by Robert L. Tonsetic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

A Winter’s Tale

“It’s with inexpressible pain that I now inform your Excellency of the general mutiny and defection which suddenly took place in the Pennsylvania Line, between the hours of nine and ten o’clock last evening.”

—General Anthony Wayne

January 2, 1781

January 2, 1781

1

THE DARKEST NEW YEAR

After crossing numerous frozen streams and struggling through treacherous snowdrifts with bone chilling winds howling around them, the small party of horsemen reached Army headquarters in New Windsor late in the afternoon on January 1, 1781. Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys’ grueling three-day, near hundred-mile journey from Brunswick, New Jersey to New Windsor, New York, was at an end. The twenty-nine-year-old dismounted his horse and handed the reins to one of the grooms tending several horses outside the modest two-story Dutch farmhouse that served as Washington’s headquarters. Several sentries were posted around the house trying to ward off the cold by stomping the ground to keep their feet warm, clutching their muskets close to their bodies at order-arms under their cloaks. Bounding up the snow-covered steps and onto the wrap-around porch, Humphreys stomped the snow off his boots, and after returning the salute of the sentry posted at the door, he entered the house prepared to render his report on his unsuccessful mission to his commander-in-chief. The New Year, 1781, was off to an inauspicious start.

ARMY HEADQUARTERS—NEW WINDSOR, NEW YORK

January 1, 1781

January 1, 1781

January 1, New Year’s Day, was a major holiday in eighteenth century America, even during wartime. A popular way of celebrating the passing of the old year and the arrival of the next was to hold open houses and to go visiting friends and neighbors.1 Thus, there was only a minimum of staff work conducted at Army headquarters on New Year’s Day 1781. Most of the day was spent receiving guests. In keeping with Army customs, subordinate commanders, whose units were in winter quarters nearby, called upon the General and his Lady at their residence. Additionally, in keeping with local Dutch custom, George and Martha Washington also received civilian guests from the local community. Appointments and invitations were unnecessary. Despite his deepening concerns about the future of Army and its prospects for victory, the Army’s commander received his guests with the utmost courtesy and respect. His reserved, genteel manner belied the increasing level of stress that he felt.

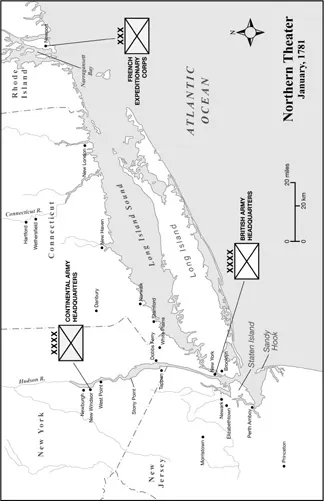

The day prior, the General had returned to his winter headquarters exhausted after an inspection trip of the fortifications and garrisons at West Point, some ten miles downriver from New Windsor.2 It was Washington’s second recent visit to the area, reflecting his growing concern for the security of the fortifications at the Point. West Point was the linchpin of the American defenses in the strategic Hudson corridor. If the British gained control of the corridor, they would sever the lines of communication between the New England States and the rest of the newly declared nation. Benedict Arnold’s plot to turn the fortifications over to the British in September 1780 was a near miss. Adding to Washington’s concern was the fact that the New England regiments defending the forts at the Point had been weakened after the discharge of large numbers of levies. Additionally, Washington lacked full confidence in Major General Heath, the Highlands Department Commander, who was responsible for the security of the Hudson corridor. Approaching his forty-ninth birthday, the commander-in-chief looked, and no doubt felt, much older than his years.

After all the guests departed, Washington retired to his small office in an upstairs room, and summoned Lieutenant Colonel Humphreys to receive his report. Humphreys was one of Washington’s most trusted aides and confidants. The twenty-nine-year-old Yale graduate had been chosen by Washington to lead a clandestine expedition into British occupied New York. His mission was to capture either the sixty-year-old General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, the commander of Hessian troops, or the British commander in chief, General Sir Henry Clinton. Both the Americans and the British attempted to capture prominent general officers during the war. On more than one occasion, the British laid plans to capture Washington.

Benedict Arnold’s scheme to turn over the fortifications at West Point to the British could also have led to Washington’s capture. The general had been on his way to West Point when he learned of Arnold’s plot.

Washington selected David Humphreys to lead the covert mission based on his experience on two previous raids. During the spring of 1777, Humphreys accompanied Colonel Meigs on a successful raid on Sag Harbor, New York. A year later he led his own 30-man raiding force to the Long Island shore and destroyed three British vessels without losing a man. Washington knew that if anyone could pull off the scheme to capture Knypahusen or Clinton, it would be Humphreys.

During the evening of Christmas Day 1780, Lieutenant Colonel Humphreys’ hand-selected detachment of 27 men set out by barge and whaleboats from Dobbs Ferry on the Hudson River. Humphreys hoped to cover the 25 miles to New York City around midnight, but nature did not favor the plan. As the boats approached New York, high northwest winds swept them past their intended landing sites. One boat was driven down toward Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and another put in on a remote section of Staten Island. Over the next few days, Humphreys managed to locate all of his boats and land near Brunswick, New Jersey. From there, the raiders were able to reenter the American lines.3 The unsuccessful raid was the first disappointment of the New Year for the Americans, and a continuation of a long series of and setbacks experienced during the preceding year. Nonetheless, Washington knew that Humphreys had done his best, and he was relieved when his trusted aide returned safely with all of his men.

After receiving Humphreys’ report, Washington’s household settled in for the night, and only the groaning, creaking, and cracking of the river’s ice broke the nocturnal stillness. As Washington and Martha prepared to retire for the night another major calamity involving the American army was underway. As the General slumbered, couriers raced across the snow-covered New Jersey hills toward his headquarters bearing news that troops of the Pennsylvania Line had mutinied and were planning to march from their encampment at Mount Kimble, New Jersey to Philadelphia to present their grievances to Congress. The mutiny had the potential to trigger others throughout the ranks leading to the dissolution of the entire American army, and dooming the revolution.

DOWNING STREET, LONDON—JANUARY 1, 1781

It was a frosty, gloomy day in London. The Thames was not frozen over, but ice was beginning to form along the banks. Chimneys throughout the city belched thick clouds of black soot into the city’s foggy air. A malodorous mixture of cinder smoke, decaying garbage and open sewage kept most Londoners indoors on New Year’s Day.

Great Britain’s Prime Minister, Lord North, spent the holiday with his wife and children. There was time that day to reflect on his accomplishments as Britain’s steward. Having led his nation for ten years, the corpulent 49-year-old Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford, was the longest serving Prime Minister since Robert Walpole (1721-42). He had led Great Britain through the ups and downs of the American War of Independence, since the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775. Despite a string of victories that led to the capture of New York and Philadelphia, some of Britain’s best generals were unable to secure a decisive victory that would bring an end to the costly war. After the French allied themselves with the American rebels in 1778, Spain quickly joined the war in 1779 as an ally of France, followed by the Dutch Republic a year later. In addition, there was a lingering fear that Russia would enter the war in support of the Dutch. Within a three-year period, Great Britain had found herself in a global war on four continents, with no major allies.

After the humiliating British loss at Saratoga in 1777, and France’s entry into the war in 1778, North had offered to resign, but King George III refused to accept his resignation. Opposition to the once popular war continued to increase during most of 1780, but the headline news of major British victories at Charleston in May and at Camden in August of 1780, resulted in a gradual shift of public opinion in favor of the war. Those victories seemed to prove the efficacy of Britain’s new southern strategy, and renewed hope that the war could be brought to a successful conclusion. As a result, Lord North’s government retained its majority in Parliament after the first elections since the war began were held during the fall of 1780.

Despite the electoral victory, the Prime Minister remained deeply concerned about the war. Great Britain’s resources were stretched thin. The British army was under increasing strain due to its worldwide commitments stretching from India to North America. New regiments were needed to replace old ones that were seriously understrength due to losses on the battlefield, and from disease and desertion. Moreover, the recruitment pool was drying up, and the quality of new recruits continued to decline. The British navy was also stretched close to the breaking point. In addition to protecting the homeland from invasion, the navy was faced with the enormous task of supplying the army in North America and transporting troop reinforcements to that theater. The shipping of supplies and reinforcements was beginning to seriously restrict the execution of strategic plans in all theaters of war.4 There was also growing concern within the government about the financial costs of the effort. The national debt had almost doubled since the beginning of the war.5 Moreover, it was likely that future loans would have to be made at increasingly higher interest rates.

Lord North knew that pacifying the countryside in South Carolina, particularly the backcountry, was not going well. The American victory over the Loyalists at Kings Mountain in October of 1780 raised significant doubts about the capability of the Loyalist militias to prevail over their rebel neighbors. The year 1781 was a critical one for the British. If their southern strategy was to succeed, the rebels in South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, and the “real prize,” Virginia, had to be crushed. Lord North believed that victory over the American rebels was still possible, but only if Britain remained resolute in the coming months. If the southern strategy succeeded, Britain would, as a minimum, retain its four southern colonies. North was confident that he had the monarch’s full support in continuing the war.6

THE CHATEAU DE VERSAILLES, FRANCE—JANUARY 1, 1781

After attending mass, the sixty-three-year-old Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, Foreign Minister of France, retired to his luxurious Versailles apartments. The stately career diplomat gazed out the windows of his salon at the expansive ornamental gardens. A light dusting of snow sparkled on the trees and shrubs under the January sunlight. The Minister strode to his writing desk and opened a packet of unread dispatches.

Vergennes was appointed as France’s Foreign Minister after King Louis XVI’s accession to the throne in 1774. The appointment came after a thirty-five-year career in the French diplomatic service; all of it spent abroad. Vergennes advanced a foreign policy that was based on his conviction that Great Britain’s power was on the rise and had to be kept in check. He viewed the American War of Independence against the British as an opportunity to avenge French losses during the Seven Years’ War, and greatly diminish the British domination of North America. Vergennes’ foreign policy views were endorsed by the 27-year-old King Louis XVI, who wanted the Americans to succeed in their war for independence. Due in large part to Vergennes’ efforts, a “Treaty of Alliance” between France and the United States was signed in 1778.

Officially, the treaty was non-negotiable; however, both parties knew that alliances survive only as long as they are judged to be useful. After more than two years, Vergennes was having second thoughts about the alliance. The disturbing American losses at Charleston and Camden during 1780, along with Arnold’s betrayal, had weakened support for the war within the French ministries. General Comte de Rochambeau’s army of 6,000 troops landed at Newport, Rhode Island during the summer of 1780, but the French and American forces had yet to begin joint operations. Despite extensive correspondence, and three personal meetings, Washington and Rochambeau could not agree on a strategy for the future conduct of the war. Washington stubbornly held out for an attack on the British garrison at New York, but Rochambeau refused to commit his army, since the British fleet controlled the waters surrounding the city. France was determined to protect her interests in the Caribbean, and Admiral de Grasse’s powerful French fleet was committed to the West Indies. Vergennes was also concerned that the seemingly interminable war was driving the treasury toward insolvency, and that a peace faction was gaining strength within the French ministries. America’s appetite for more and more cash, armaments, and supplies was insatiable. Although Vergennes respected the American Minister Plenipotentiary (Ambassador) Benjamin Franklin’s intelligence and diplomatic skills, he was rapidly tiring of his endless requests for more and more military and economic assistance. On the other hand, Vergennes had little respect for American Minister Plenipotentiary John Adams. The French Foreign Minister viewed Adams, who lacked Franklin’s finesse, as an amateur in the realm of diplomacy. Vergennes was irate that the blunt provincial, John Adams, was meddling in European affairs, particularly with the Dutch.7 By the beginning of the year 1781, the French Foreign Minister knew that France’s foreign policy with respect to the United States was in serious trouble, and he was looking for a way to end the war at the negotiating table.8

2

DISORDER, FEAR, AND MUTINY

New Year’s Day was a traditional day of celebration in the Army, and the normal daily formations, drills, and work details were not scheduled. At the Pennsylvania Line’s winter encampment, the day began quietly. Most of the troops stayed in their huts, while a few ventured into the snow-covered woods to gather firewood to prepare the breakfast meal. In the officers’ quarters, preparations were underway for elegant regimental dinners complete with entertainment. For some, it would be the last time that they would dine together. In several huts, groups of sergeants met to finalize their own plans for the day. In hushed voices, the non-commissioned officers reaffirmed their determination to take action to obtain redress of their longstanding grievances. Bottles of rum passed from hand to hand as the sergeants worked out the final details of their plan.

The Pennsylvania Line was formed in 1775, and was originally comprised of thirteen regiments and several independent companies. Along with the Massachusetts and Virginia Continentals, the Pennsylvania regiments provided the backbone of the American army. During the first five years of the war, the Pennsylvania regiments fought heroically in most of the major battles in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, including Brooklyn, Stony Point, Trenton, Princeton, Monmouth, Germantown, and Brandywine. Casualties suffered in those battles were significant, and the number of replacements was never adequate to fill each regiment’s ranks. It made no sense to continue the war with “hollow” regimental formations on the battlefield. Something had to be done

Under a reorganization plan for the Continental Army that became effective on January 1, 1781, the Pennsylvania Line was consolidated into six infantry regiments, an artillery regiment, a legionary corps, and an artificer regiment. The reduction in the total number of Line regiments was necessary due to battlefield losses, non-battle casualties, and desertions. Recruitment of replacements was increasingly difficult after the harsh winters of 1777-78 and 1779-80. The reorganization did not affect the terms of enlistments of the men serving in the ranks. The companies of the deactivated regiments were transferred to one of the remain...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography