- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Spotlights the career of a fascinating modern warrior, while also shedding light on some of the conflicts that have raged throughout the world" (

Tucson Citizen).

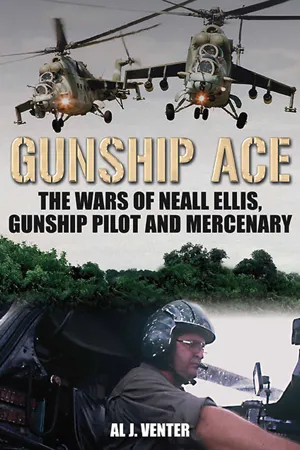

A former South African Air Force pilot who saw action throughout the region from the 1970s on, Neall Ellis is the best-known mercenary combat aviator alive. Apart from flying Alouette helicopter gunships in Angola, he fought in the Balkan war for the Islamic forces, tried to resuscitate Mobutu's ailing air force during his final days ruling the Congo, flew Mi-8s for Executive Outcomes, and piloted an Mi-8 fondly dubbed "Bokkie" for Colonel Tim Spicer in Sierra Leone. Finally, with a pair of aging Mi-24 Hinds, Ellis ran the Air Wing out of Aberdeen Barracks in the war against Sankoh's vicious RUF rebels. As a "civilian contractor," Ellis has also flown helicopter support missions in Afghanistan, where, he reckons, he had more close shaves than in his entire previous four decades.

From single-handedly turning the enemy back from the gates of Freetown to helping rescue eleven British soldiers who'd been taken hostage, Ellis's many missions earned him a price on his head, with reports of a million-dollar dead-or-alive reward. This book describes the full career of this storied aerial warrior, from the bush and jungles of Africa to the forests of the Balkans and the merciless mountains of Afghanistan. Along the way the reader encounters a multiethnic array of enemies ranging from ideological to cold-blooded to pure evil, as well as examples of incredible heroism for hire.

A former South African Air Force pilot who saw action throughout the region from the 1970s on, Neall Ellis is the best-known mercenary combat aviator alive. Apart from flying Alouette helicopter gunships in Angola, he fought in the Balkan war for the Islamic forces, tried to resuscitate Mobutu's ailing air force during his final days ruling the Congo, flew Mi-8s for Executive Outcomes, and piloted an Mi-8 fondly dubbed "Bokkie" for Colonel Tim Spicer in Sierra Leone. Finally, with a pair of aging Mi-24 Hinds, Ellis ran the Air Wing out of Aberdeen Barracks in the war against Sankoh's vicious RUF rebels. As a "civilian contractor," Ellis has also flown helicopter support missions in Afghanistan, where, he reckons, he had more close shaves than in his entire previous four decades.

From single-handedly turning the enemy back from the gates of Freetown to helping rescue eleven British soldiers who'd been taken hostage, Ellis's many missions earned him a price on his head, with reports of a million-dollar dead-or-alive reward. This book describes the full career of this storied aerial warrior, from the bush and jungles of Africa to the forests of the Balkans and the merciless mountains of Afghanistan. Along the way the reader encounters a multiethnic array of enemies ranging from ideological to cold-blooded to pure evil, as well as examples of incredible heroism for hire.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gunship Ace by Al J. Venter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

FORMATIVE DAYS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA

Neall Ellis’s determination to hew his own path in life can be traced back to his youth and, more precisely, to his experiences as a schoolboy in Bulawayo and, later, in Plumtree, both in the south-west of what is now Zimbabwe. In colonial times it was known as Southern Rhodesia, or simply Rhodesia.

Born of good British stock in South Africa’s great mining and financial centre of Johannesburg on 24 November 1949, he didn’t live there long. Six weeks later his father moved the whole family to Rhodesia. At the time, Ellis Senior was general manager of Gallo Africa, a major music production and sales company, probably the biggest of its kind in Africa. Originally from Woolwich, near London, he had come out to South Africa with the Royal Navy during World War II. He had served on board the battleship HMS Royal Sovereign on Arctic convoy runs, shipping vital supplies to the Soviet port of Murmansk in Russia. His service with the RN also took him to South Africa where, in Simonstown—then a British naval base—Leslie Thomas Ellis met and married Ruby Sophia Hyams. ‘My mother’s side was very Afrikaans—they were Vissers—while my grandfather’s name was Hyams’, recalls Neall.

The move to Bulawayo brought many changes, including a number of different homes in the city. As Neall recalls: ‘My parents encouraged us to be pretty independent … we were strictly disciplined and my mother used to thrash us with a wooden coat hanger, but it would always break, so it wasn’t too bad!’

There were two large dams, not far from home, where the kids would fish: ‘Mom was petrified whenever we went near either of them, having already lost one son to drowning. However, we were taught to swim at a very young age—something like three or four.’

In one of the family homes, at Hillside, on the side of a kopje at the back of the house, the youngsters played their games in the nooks and crannies of the rocks and they would sometimes encounter cobras or other bush creatures that had ventured in from the wild.

We never thought too much about it—the snakes would give us a wide berth if they sensed our approach and we would duck away if we saw them—got spat at by a Cape cobra a few times, though.

At the time, Dad was very friendly with a man named Alan Boyle, an Australian, and both men were what you’d call ‘party animals’. They would go up north into Africa, driving or chartering a light aircraft, the idea being to make recordings of traditional African music which Dad loved. It was all the kind of antiquated reel-to-reel stuff that you never see today, bulky, testy old machines.

Neall believes that his father’s interest in this aspect of ‘Black Culture’ was the start of old man’s Eric Gallo’s specialisation in traditional African music, for which the company later became known. More important to the Ellis children at the time, their father would return from his trips with lovely ebony masks and other African carvings, curios and a huge variety of native trivia on which tourists today spend good money. Neall recalls: ‘One morning I went into the kitchen and opened the fridge. There was a candy box and inside, one great big lump of elephant shit!’

Growing up, young Neall remembers lots of weekends when the family and their friends went up into the Matopos Hills on picnics. Rhodes lies there, watching over the country once named for him, under a brass plate set into granite over his grave on the summit of one of the gomos.1

Meanwhile, the kids would play games, such as kennietjie. This game would start with a groove being dug in the ground. Then one of the youngsters would take a twig and lay it across the groove, before flicking it with a stick and someone else had to catch it. These were the kind of pastimes that children of the original Pioneer Column must have played of an evening after they had unhaltered—or as we liked to say, outspanned— their oxen following a long day’s trek. Neall recounts:

I was fascinated by the historical impact of the area, especially what that tiny band of settlers who had followed in the wake of Cecil John Rhodes’ dream had achieved. There were lots of stories of these rugged, tough pioneers, almost all of them frontiersman like Alan Wilson and his Shangani Patrol … and their bloody and terrible end under the spears of Lobengula’s Ndebele warriors. There was a great lore, a fine historical tradition in all those tales that were recounted around the fire in the evenings, and I was fascinated. It was the same when my grandmother introduced me to the history of the Zulu people and their tribal cousins, the Ndebele, who moved northwards into Rhodesia long before the white man got there.

Early Rhodesian Department of Information photo of troops on deployment in the bush. Photo: Original Rhodesian government recruiting photo

It was possibly these interests that helped give Neall the ease with which he later crossed racial and social barriers, some real, some imagined, but strong, for all that. Race, then, was a feature of life in South Africa in the days of apartheid, and, while far less rigid and formalized in the Rhodesia of his youth, he recalls today that you really couldn’t miss the innuendos that involved ‘them and us’.

Among some of the first of the historic tales that young Neall can recall hearing was one told to him in the late 1950s about what was to become known as the ‘First Chimurenga War’, or the first liberation struggle of Rhodesia’s black population. As with similar rebellions against white settler communities in German-ruled Tanganyika and what later became known as South-West Africa before the start of the First World War, Rhodesia’s Chimurenga was an uprising against the white settlers of Rhodes’ British South Africa Company.

Most of it, as I recall, was passed on to us young people from the victors’ (white) side … but then that is how history usually emerges, kind of like ‘to the victor the spoils’. They used to have military tattoos at the Bulawayo Showground, with re-enactments of the mounted patrols on their horses, all very well done and actually quite impressive. Then, the African Impis—the black warriors in their proud headdresses, hardened cow-hide shields and assegais—would surround them, and there would be lots of firing and yelling ‘and the whiteys would see their gats. [An Afrikaans expression, impolitely translated as ‘seeing their arses’.]

Those family picnics in the magnificent Matopo Hills also gave Neall what he calls ‘the start of my love for the bush’.

We looked for what we called the ‘Resurrection Plant’. You found it in Rhodesia on the hills; it never totally dies. It’s a growth that survives on top of a rock in the dry winter months, just a blackened twig, but you place that ‘dead’ twig in a glass of water, and in just a couple of days, its leaves begin to sprout … that’s the Resurrection Plant.

Neall had one older brother, Peter, whom he never knew: Peter had drowned ‘just before I was born—some six months before’. His younger brother Ian today lives in Johannesburg, while his sister Janine (they were born 18 months apart) is married and is in Australia. The family remains in contact and despite distance—he is in Afghanistan most of the time these days—they stay close.

When he was old enough, Neall was sent to Hillside Junior School, which soon enough taught him about the unpleasant consequences of human relationships going awry.

There was a gang of us boys; we used to cycle home together. But it was pretty brutal. If one member of the gang fell out, there would be a fight, either with the leader of the mob, or with someone whom he nominated, in a little ‘arena’ among the rocks. One might have had absolutely no quarrel with that individual, but one still had to tough it out and it could sometimes be quite vicious.

‘From that came my hatred of bullying’, he says thoughtfully. Is it too much of a psychological leap to wonder whether this realization would, in future decades, lead Neall Ellis to feel no qualms about meting out swift and terminal justice to those, such as Foday Sankoh’s brutal killers in Sierra Leone, whose behaviour had taken them beyond the bounds of normal humanity?

In other ways, growing up in Rhodesia was a marvellous, privileged existence, with a vast hinterland waiting to be discovered and unending promises for the future. There was barely a family who didn’t have at least one servant—some of Neall’s wealthy friends had four, or even six, one for the garden, perhaps two for the kitchen, a domestic worker for bedrooms and cleaning and perhaps a driver who would take the children to school each morning and fetch them later in the day. It was an idyllic life.

That their country was landlocked didn’t keep them from the sea either. Families would sometimes drive, or take the then extremely efficient rail link to South Africa’s Indian Ocean coastline and its Natal beaches. So many families would gravitate to Cape Town during the Southern hemisphere summer holidays that there was even a resort near Simonstown which was for many years called Rhodesia by the Sea.

For the young Neall, however, holidays generally meant a much shorter journey. His maternal grandmother, Petronella, had divorced Neall’s Hyams grandfather and married Dougal Nelson, a Scot. They lived in Tzaneen, in the Northern Transvaal (now the Limpopo Province of South Africa), and farmed citrus fruits and bananas. They also made a home from home for their visiting grandchildren, a welcome that Neall still recalls with delight. The same applied when the Nelsons sold the farm and moved to Mooketsi, after grandmother Petronella started having health problems from smoking too many of the then-popular Springbok cigarettes.

Life was not always tranquil, however. One day in Tzaneen, he remembers, they were playing and his sister had the role of ‘madam’ and he was the ‘garden boy’.

I swung the hoe and although it was unintentional, it was a vicious blow and I cut open her head. My granny could be rather a fierce woman and I recall running away and hiding in the bush … but grandmother represented overwhelming odds and it was futile to resist and she meted out swift justice, much more efficiently than my mother… .

He has many happy memories of his time there as well:

We would always spend our school holidays there. On the farm we drank fresh milk but not much else but good food and healthy living: there was no electricity, no television, only Springbok Radio to listen to.

He well remembers the British series ‘Men from the Ministry’.

Meantime, other interests also took his fancy. ‘Grandmother possessed a fine collection of classical music—all old 78 vinyl records—which we played on a battery-operated gramophone’. Neall’s eclectic tastes in music remains a feature of his life.

‘Those were great times. We used to go into the bush and collect kapok, a form of vegetable down, from the seedpods of the kapok trees to fill our pillows.’ He also learned to collect mushrooms—while discarding unsuitable varieties—and today, in his sixties, he can still be seen running around when circumstances allow and inquiring from local residents about spots where edible mushrooms might be found.

‘Yes, I am rather interested in mushrooms. If I go into the Knysna Forest, I’ll pick them to eat, or to dry for cooking later.’

From Mooketsi, young Neall could look out of the kitchen window towards the Modjadji Hills and marvel at the lightning strikes flickering around the surrounding peaks. They were caused by the incredible electrical storms, which are always a summer feature of the region. ‘Perhaps that’s why I don’t mind loud bangs’, Neall comments thoughtfully.

Neall’s uncle regularly hunted for guinea fowl and bush pig, all of which supplemented the family’s regular diet.

‘He took me out into the bush with him. Grandmother had an old Richards and Harrington single-barrel shotgun with a hammer action that could nip you sharply if you weren’t too careful. There was also a .22 Savage rifle: I’ve still got them both,’ says Neall, who from the age of ten was allowed by his grandmother to go out alone and hunt.

Wildlife in the area was not always for hunting and eating. ‘I’ll never forget the snakes, particularly at Mooketsi … cobras—lots of them and puff adders. There were also twig snakes and boomslangs …’ he recalls thoughtfully. ‘A black fellow who I got to know quite well taught me about snakes, and also my grandmother, who had a reference library of her own with some quite old books, and I learned a lot about these creatures from them as well.’

As he reminisces, life—and death—could be pretty rough at times, and in those days people simply had to learn from a young age how to accept responsibility and look after themselves … and, of course, others.

One time, one of the labourers’ wives got bitten by a snake—I was about 14 at the time—and grandmother gave me the snakebite serum and told me to go and find out if the woman had actually been bitten by a poisonous snake and, if so, give her the necessary injection. Not that I’d ever used a syringe before … I realise now that had I actually injected her, it would probably have been the worst thing to do. For a start, I had no idea what species of snake it was, or even if there had been a snake to start with. I’m sure she lived, even though I didn’t give her the serum, because nobody complained.

Snakes weren’t the only danger in this remarkable Garden of Eden south of the Limpopo. ‘Grandmother had her own flock of geese and they could be formidable. There was a big gander called Shake and he guarded his flock with a passion … he’d nip you on your backside if you were slow and it was amazing how painful the bite could be’, Neall recalls.

There was also a large reservoir that was used to store water for the farm, where the young Ellis siblings used to swim. ‘But it was full of algae … and water scorpions and the little buggers used to bite you.’

Likewise, he says, there were so...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Author Page

- Dedication

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- 1 Formative Days in Southern Africa

- 2 Early Days in the South African Air Force

- 3 Early Days During the Border War

- 4 Soviet SAMs versus Helicopters in the Bush War

- 5 Into Angola with the Gunships

- 6 Death of a Good Man

- 7 Koevoet, Night Ops and a Life-Changing Staff Course

- 8 New Directions—Dangerous Challenges

- 9 Executive Outcomes in West Africa

- 10 Into the Congo’s Cauldron

- 11 On the Run Across the Congo River

- 12 Back to Sierra Leone—The Sandline Debacle

- 13 Taking the War to the Rebels in Sierra Leone

- 14 The War Gathers Momentum

- 15 The War Goes On … and On …

- 16 The Mi-24 Helicopter Gunship Goes to War

- 17 How the War in Sierra Leone Was Fought

- 18 Operation Barras—The Final Phase in Sierra Leone

- 19 Iraq—Going Nowhere

- 20 Air Ambulance in Sarawak

- 21 Tanzania

- 22 Neall Ellis Flies Russian Helicopters in Afghanistan

- Endnotes