![]()

Introduction

WE’VE ALL SEEN THE MOVIE, and as is so typical of any Hollywood blockbuster, it has defined the battle for many people. Relying heavily on a few vocal sources, it had to find a villain and he was provided by someone who could not defend himself: “Boy” Browning was dead. The willful supression of the intelligence of two “crack” SS-Panzer Divisions; the wrong crystals taken for the radios; the tardiness of the British armor at Nijmegen—in the end, the power of mass-market cinema has helped obscure the reasons for the failure of Operation Market Garden, a daring attempt to use the First Allied Airborne Army to end the war by Christmas.

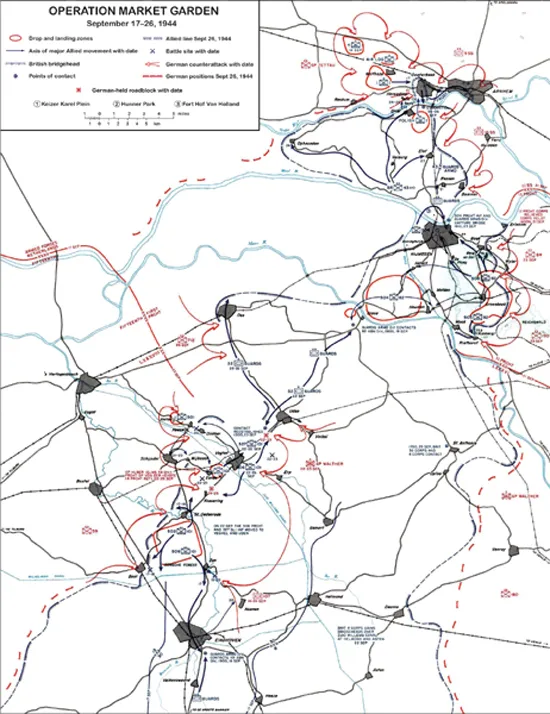

In fact, as Martin Middlebrook so succinctly outlines in the final section of his book on the Airborne battle, the real reasons behind the failure of the plan have been identified, with—on the Allied side— the air plan being pivotal. The inflexibility of Maj-Gen. Paul Williams, commander of IX Troop Carrier Command, meant that the British troops were dropped over three days, miles from the bridge, without the sort of coup de main operation that had proved so successful on the Orne on D-Day. The German assessment of the battle suggested the Allies’ chief mistake was this protracted, three-day landing. Added to this, no ground-support missions could be flown while the air drops were taking place, and that included Flak suppression.

It seems incredible but the man in charge of close air support over the Arnhem area—the commander of 2TAF, AM Sir Arthur Coningham—was not invited to attend any of planning meetings until the day before the operation, when the weather was too bad for him to attend. This meant that the first ground-support mission flown directly in aid of the Paras in the front line was not till September 24.

The ground-support missions weren’t helped by the fact that the US Air Support Signals Team, the 306th Fighter Control Squadron which accompanied the Paras in four Wacos from Manston, had been given the wrong crystals and were unable to make contact with their air assets. Apart from this, the problems with radio communication, so often alluded to (not least by Maj-Gen. Roy Urquhart), were not down to poor or inadequate equipment but basic procedural errors.

Dropped so far from the bridge over a three-day period, the division needed to protect the LZs and DZs against enemy interference, thus reducing significantly the number of troops heading for the bridge and speed with which they traveled. This, in turn, meant that the immediate German response to the airborne operation—ad hoc groupings of whatever troops were to hand, not the reaction of heavily armed “crack” SS troops, which were anyway at only 20–30 percent of their established strengths—was remarkably effective, in a way that would have almost certainly not been the case in the face of larger numbers of troops. Without the blocking action of KG Krafft, the Airborne Recce Sqn jeeps may well have reached the bridge; without the actions of KG Spindler on September 17–18, Frost’s 2nd Para Battalion would have received vital reinforcements and ammunition.

Robert Kershaw’s brace of Arnhem books supply a lucid account of the German side of the operation and highlight this speedy response to the arrival of 1st Airborne. As he says in his assessment, “too often Allied historians have tended to blame mistakes rather than effective countermeasures.” The speed of the German reaction was crucial to their success. On September 7 six British battalions landed near Arnhem. By midnight—less than twelve hours after the first Para had dropped—there were between ten and eleven German battalions opposing them, their troop movements having taken place without harassment by Allied close air support. By September 20 the Germans had a three-to-one advantage. They had, as Kershaw points out, won the reinforcement battle.

The Airborne badge depicts Bellerophon riding Pegasus. It was designed by Edward Seago, from a suggestion by the famous novelist Daphne du Maurier, the wife of Maj-Gen “Boy” Browning, commander of 1st Airborne. It was worn by all British Airborne troops.

American Lt-Gen Lewis Hyde Brereton (1890– 1967) commanded the newly constituted First Allied Airborne Army with the British Lt-Gen Frederick Browning (1896–1965) his deputy.

The plan was to thrust through to the Rhine, opening up the north German plains and the road to Berlin, and the encirclement of the Ruhr. Strategically, it made a great deal of sense: the German army had been in full flight since the closing of the Falaise Gap. In fact the Allied armies had advanced faster than the German Blitzkrieg of 1940. And then there was the First Allied Airborne Army, a huge special force pushing to be used—the American and British Airborne troops had been agitating to get into the action and Market Garden was the last in a series of potential operations. The US 82nd and 101st Divisions dropped along the corridor, taking the bridges and holding “Hell’s Highway”open for British XXX Corps to advance to Arnhem. Delays frustrated this advance and led to the failure of the operation one bridge short.

Part of the reason for this was that the Germans were able to divert reinforcements heading towards the US First Army sector—for exam...