eBook - ePub

The Last Hot Battle of the Cold War

Decision at Cuito Cuanavale and the Battle for Angola, 1987–1988

- 235 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Last Hot Battle of the Cold War

Decision at Cuito Cuanavale and the Battle for Angola, 1987–1988

About this book

A fascinating chronicle of the Cold War battle where US and Soviet weapons, as well as Cuban and South African troops, took part in the Angolan Civil War.

In the late 1980s, as America prepared to claim its victory in the Cold War over the Soviet Union, a bloody war still raged in Southern Africa, where proxy forces from both sides vied for control of Angola. The socialist Angolan government, stocked with Soviet weapons, had only to wipe out the resistance group UNITA, secretly supplied by the United States, in order to claim sovereignty. But as Angolan forces gained the upper hand, apartheid-era South Africa stepped in to protect its own interests. The white army crossing the border prompted the Angolans to call on their own foreign reinforcements—the army of Communist Cuba.

Thus began the epic Battle of Cuito Cuanavale: an odd match-up of South African Boers against Castro's armed forces. While South Africa was subject to an arms boycott since 1977, the Cuban and Angolan troops had the latest Soviet weapons. But UNITA had its secret US supply line, and the South Africans knew how to fight. As a case study of ferocious fighting between East and West, The Last Hot Battle of the Cold War unveils a remarkable episode in the endgame of the Cold War—one that is largely unknown to the American public.

In the late 1980s, as America prepared to claim its victory in the Cold War over the Soviet Union, a bloody war still raged in Southern Africa, where proxy forces from both sides vied for control of Angola. The socialist Angolan government, stocked with Soviet weapons, had only to wipe out the resistance group UNITA, secretly supplied by the United States, in order to claim sovereignty. But as Angolan forces gained the upper hand, apartheid-era South Africa stepped in to protect its own interests. The white army crossing the border prompted the Angolans to call on their own foreign reinforcements—the army of Communist Cuba.

Thus began the epic Battle of Cuito Cuanavale: an odd match-up of South African Boers against Castro's armed forces. While South Africa was subject to an arms boycott since 1977, the Cuban and Angolan troops had the latest Soviet weapons. But UNITA had its secret US supply line, and the South Africans knew how to fight. As a case study of ferocious fighting between East and West, The Last Hot Battle of the Cold War unveils a remarkable episode in the endgame of the Cold War—one that is largely unknown to the American public.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last Hot Battle of the Cold War by Peter Polack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Afrique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

CUITO CUANAVALE—AN OVERVIEW

Originally this colony was known as Portuguese West Africa. Its name was changed to Angola in the early 1950’s with the province of Bie being divided into what are still the two largest provinces of the country, Moxico and Cuando Cubango, which are hundreds of thousands of square kilometers in area. The province of Moxico was the UNITA heartland throughout the war and it was here that the UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi was killed in 2002 with the invaluable assistance of Geraldo Sachipengo Nunda, one of Savimbi’s former generals. Nunda was a former UNITA brigadier who crossed over and is now head of the Angolan army.2

The old colonial capital of Cuando Cubango was also called Serpa Pinto, which is the name usually applied to the nearby air base that was the center of Cuban-assisted air operations during the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. The name of the capital was changed to Menongue after independence and it is usually associated with the supply staging point for the battle that was to come. Cuito Cuanavale, or Kwito Kwanavale, was a small town in Cuando Cubango province in the heart of Angola, built on the confluence of the Cuito and Cuanavale rivers.

During the Portuguese colonial era, river crossings of the Cuito River were made by wooden ferry using a large log raft called a “jangada,” with the vehicle perched precariously on this unstable platform. The ferry was anchored to each bank by a steel cable attached to tree stumps, and several men would then pull it across the crocodile infested body of water. It was only some time later that a bridge was constructed across the river to firmly connect Cuito Cuanavale.

The Portuguese colonialists referred to this area as the land at the end of the earth, probably because it was far from the developed and civilized parts of the country. It lay some 400 kilometers from the northern border of the now-independent state of Namibia, which was occupied by South Africa at the time of the Angolan or Bush war.

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale took place east of the town, which had a crucial airfield for resupply of the defending Cuban and FAPLA units who were the ultimate target of the attacking SADF and UNITA forces. The actual battlefield was on both sides of the Tumpo River, 22 kilometers east of Cuito Cuanavale, and was part of what is sometimes called the Tumpo triangle of Angola. Many contemporary military analysts believed that the capture of Cuito Cuanavale would provide the gateway to Luanda, the capital of Angola, to the SADF and UNITA forces, and the potential for a complete UNITA victory.

Interestingly, UNITA was able to capture large swaths of Angola after the departure of the SADF and Cubans in 1989, proof positive of the ability of the Angolan soldier and the strength of UNITA’s military leaders like General Ben Ben.

This battle has been variously described as Africa’s largest land battle since World War II, the African Stalingrad, Angola Verdun, El Giron Africano (a play on the Cuban name for the aborted Bay of Pigs invasion), or more accurately the largest single conventional military engagement on the African continent since the Battle of El Alamein. This is a realistic comparison because both conflicts involved extensive logistical supply problems for the warring factions.3

The battle near the town of Cuito Cuanavale took place between November 1987 and April 1988, but had its genesis much earlier in the repeated failures by Soviet-led FAPLA forces to seize the UNITA headquarters to the west at Jamba. This was the consequence of a 1984 change in Soviet strategy to move from protection of cities, towns, and facilities to an active and aggressive counterinsurgency against UNITA. In this, they fell into the open arms of the American post-Vietnam policy of a cheaper option: supporting the UNITA guerillas. This particular engagement grew out of a misguided Soviet operational plan to attack the UNITA controlled stronghold town of Mavinga and then continue onward to Jamba. Mavinga had an important UNITA airstrip used by the South African Air Force (SAAF) and others to bring supplies and weapons to the UNITA army as well as a blood diamond trading post. The FAPLA viewed the closer town of Mavinga as a strategic portal to the UNITA headquarters at Jamba.

UNITA liaison officer SADF Col. Fred Oelschig recalled Mavinga:

There were absolutely no fortifications and in my opinion, the only military value that the town had was the very good ground runway nearly two kilometers in length. The town consisted of only two roads; a short North/South road running from the river to the runway, past the house of the governor and a long East/West road running parallel to the runway where the school, post office and other lesser houses were situated. The town had been destroyed in previous battles between UNITA and FAPLA after 1975. The area was primarily an agricultural area where UNITA farmers produced maize in vast lands adjacent to the Mavinga river valley. The general Mavinga area of 100 square kilometers, however, was occupied by a number of UNITA bases: West of Mavinga at the confluence of the Cunzumbia and Lomba rivers was a large UNITA logistical base; East of Mavinga [approximately 30 km] was another large UNITA log base and a regional hospital; North of Mavinga, East of Cuito Cuanavale, at the source of the Cunzumbia River was a large UNITA training base. I was personally astounded as to why FAPLA (and their advisors) were so adamant about Mavinga—they made four attempts at taking the place, each time using the same routes and tactics [which only serves to prove the inadequacies of the Soviet military doctrine]. In my opinion, there were a number of other options available to them. If FAPLA had broken up their mobile forces into smaller combat teams and had advanced across a much broader front then I believe that they could have been more successful, but the Soviet military doctrine does not allow that degree of independent action for its commanders; therefore, it is always a nonstarter.

The Soviet plan was a manifestation of the commonplace military obsession with a knockout blow: the quest for a single, swift decisive strike that will bring victory, which more often than not proves misguided in conclusion and disastrous in implementation. “Shock and Awe” from America’s war in Iraq comes to mind. The Soviet and American leadership sought knock out blows, for example, the bombing campaign of North Vietnam and control of the Afghanistan countryside. These theories failed and became incrementalism.

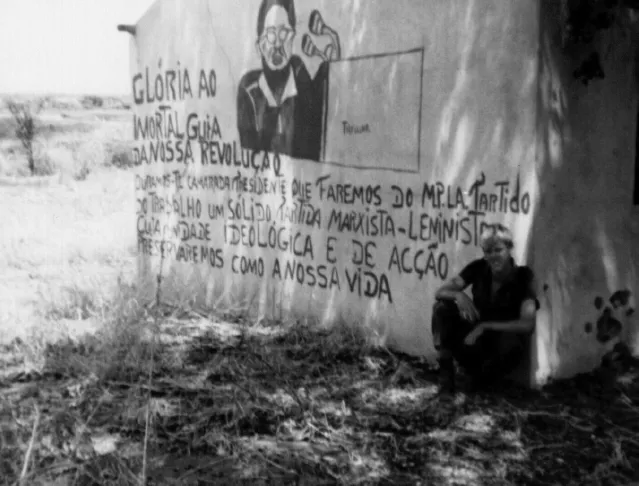

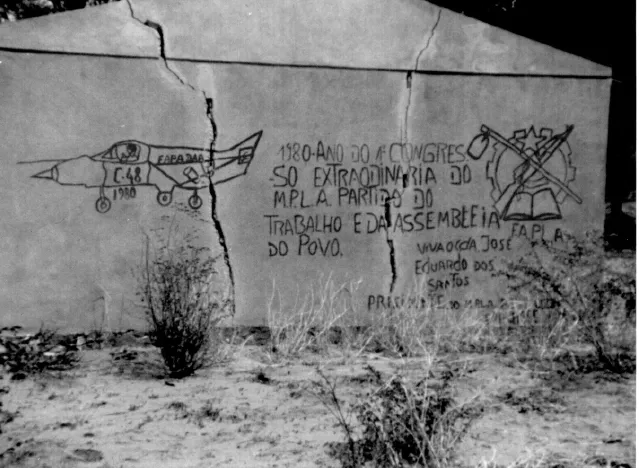

MPLA proppganda on buildings in Mavinga.—Richard Wiles

The attack was originally planned in 1986 by Soviet chief military advisor Lt. Gen. Leonid Kuzmenko and later by his successor Lt. Gen. Pavel Gusev in 1987, advised by counterinsurgency expert Gen. Mikhail Petrov. The Soviet leadership decided to take over command of all Angolan and allied forces, mostly Cuban and a few East German, which led to the issue of a directive in February 1987 for the dry season offensive to be directed at Mavinga via the Lomba River in Eastern Angola.4

The Cuban high command, with greater experience in this type of war, undoubtedly had superior tactical knowledge in this instance when compared to the FAPLA Russian advisors and expressed doubts about the likelihood of success of such an attack. As Edward George pointed out in his book The Cuban Intervention in Angola, 1965–1991: “Once again, however, the Soviets failed to make contingency plans for a South African intervention, despite being warned in May 1987 by Ronnie Kasrils [one of MK’s most senior commanders in Angola] that an SADF invasion from Namibia was imminent. [Umkhonto we Sizwe or MK was the armed wing of the African National Congress.]5

This warning proved correct to the grave misfortune of the FAPLA forces and their senior Soviet advisors, who turned tail and were evacuated by helicopter when the going became hellish, a repeat of their cowardly actions in October 1985. The FAPLA were substantially left without the leadership that led them into the disaster for several months until relief by Cuban reinforcements west of the Tumpo River near Cuito. However, one source does suggest that some lower level advisors had to retreat with the FAPLA forces, paying the price for being left behind. There was limited evacuation capacity in the circumstances presented at the Lomba River, so it’s not surprising that only the senior advisors made it out by helicopter.6

South Africa’s initial objective was to secure the Jamba headquarters of the UNITA forces concentrated there as well as keep the area north of Rundu on the Namibian border clear of any SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization) activities by occupying that area. SWAPO was the Namibian liberation movement that were militarily active in resisting South African control of their country by guerilla tactics and whose struggle led to Namibian independence in 1990. Significantly, Norway, the home of the Nobel Peace Prize, began to give direct aid to SWAPO starting in 1974.

Other FAPLA concerns were initially voiced about the supply distance in unfriendly UNITA territory, the high financial cost to the FAPLA with their limited resources, as well as insufficient air cover which made the operation precarious. Despite all this, and with stern Soviet insistence, the FAPLA offensive began from Cuito east towards Mavinga with the FAPLA 21st, 25th, 47th, 59th, and 16th Brigades.7

It was to be a bloody and unfortunate mistake rooted in post-Stalinist military apathy that FAPLA General and Minister of Defense Pedro Maria Tonha, also known by his nom de guerre Pedalé, would regret until he died prematurely in London in July 1995.8

CHAPTER 2

THE CUBAN FORCES

At Freedom Park, outside South Africa’s capital city of Pretoria, is the Sikhumbuto Wall monument that includes the 2,106 names of Cuban soldiers who fell in Angola between 1975 and 1988. This is about 160 Cuban casualties per year in Angola, an extremely low casualty rate for this type of war, if you accept this figure. This was a tribute to the parsimonious and priority use of troops by the Cuban leadership. The Cubans used their substantial number of troops in a very careful manner. No wild rush attacks on UNITA positions or chasing units across the countryside. Although they were advisors, often large numbers of Cubans were used for defensive actions or security operations for important assets like oil installations.9

Among the Cuban troops sent to Angola was former Col. Pedro Tortolo Comas, the failed commander of Cuban forces in Grenada now sent to Angola as a private along with most of his Grenada command. Tortolo allegedly hid in the Soviet embassy during the United States invasion of Grenada.

On 26 October 1983, the second day of American invasion, Commandante Castro made the following announcement on the Havana Television Service:

I feel that organizing our personnel’s immediate evacuation at a time when U. S. forces were approaching would be highly demoralizing and dishonorable for our country in the eyes of world public opinion. The people know of the message exchanged between the commander in chief and Colonel Tortolo, the man in charge of Cuban personnel. This man, who had barely been in the country twenty-four hours on a working visit, with deeds and words has written in our modern history page worthy of Antonio Maceo. Fatherland or death, we shall win.10

Cuba suffered a massive embarrassment and propaganda blow when Cuban Air Force (DAAFAR) Brig. Gen. Rafael del Pino defected to the United States with his family in May 1987. Del Pino severely criticized the incompetence of Cuban commanders in Angola, apparently in silent agreement with Cuba’s commander in chief as events were to unfold. Worse was the misleading of relatives as to circumstances of the noncombat deaths of family members being described as heroic. He exposed how many Cuban soldiers were being buried in Angola, which may have led to the later refrigerated repatriation of Cuban remains described below and the confusion on actual Cuban casualty numbers. The later, Cuban-led turnaround at Cuito did not support del Pino’s theory of a debacle and Angolan Vietnam but there was great truth in his view of Cuban officer discontent.11

All Cubans between the ages of seventeen and twenty-eight, men and women alike, are required to perform two years of military service with provisions to work in other areas other relating to the national security of the country in place of uniformed service. Internationalist combat units are usually all volunteer but refusal to fight abroad would have employment, academic, and other consequences for young Cuban soldiers who did not wish to volunteer for overseas duty.

Many SADF conscripts found themselves deployed in a foreign country, Angola or Namibia, without any choice in the matter. The Cuban forces that arrived in Angola, however, were portrayed as volunteers supporting the popular decision in Cuba to protect Angola. The compelling report below did not support this notion.

An interview of a Cuban combat veteran of Angola was done in Panama City, Republic of Panama, by Professor Russ Stayanoff and was published in Small Wars Journal in May 2008 titled “Third World Experience in Counterinsurgency—Cuba’s Operation Carlotta 1975”:

Ernesto C. is a tall, handsome, slightly graying man in his early fifties. He has lived for several years in Panama City, Panama, where he is a kitchen manager for a family owned Cuban restaurant. His soft-spoken manner and forced smile betrays a man whose life experiences are neither gratuitously given nor easily recounted. In 1975, at the age of sixteen, Ernesto was living with his mother in the Province of Havana, having just graduated from high school. Life was poor but predictable and he was looking forward to entering the University of Havana with his classmates. By law, university ambitions of all young Cubans were put on hold until the two-year compulsory military service obligation was satisfied. Within months of his graduation, Ernesto reported for his military training.

According to Ernesto, Cuban military entrance requirements at the time of his induction were quite lax, “ . . . one only had to pass a medical exam. If you weren’t deaf, blind or missing a leg you were in. It was obligatory, so there were no special considerations. “Ernesto joined other sixteen and seventeen year old males called up from Havana Province and began 45 days of basic combat training known as “la previa.” Cuban conscripts were trained at the older isolated revolutionary-era military camps near the town of San Antonio de los Baños. Like all new soldiers, Ernesto encountered arduous training days that began early and ended late. Introduced to close order drill, physical training and weapons and marksmanship skills using the AK 47, the training company was also under the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1. Cuito Cuanavale—An Overview

- 2. The Cuban Forces

- 3. The South African Forces

- 4. The FAPLA Soviet Advisors

- 5. The Angolan FAPLA

- 6. The Angolan UNITA

- 7. General Ben Ben

- 8. The Beginning of the End

- 9. Commandant Robbie Hartslief

- 10. The Retreat

- 11. The Siege of Cuito Cuanavale

- 12. The Air War

- 13. Casualties of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale

- 14. Prisoners of War

- 15. Ceasefire

- Glosssary

- Appendix A: The Cuban Forces

- Appendix B: The South African Forces

- Appendix C: U.S.S.R. Forces

- Appendix D: FAPLA Forces

- Appendix E: UNITA Forces

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index