- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

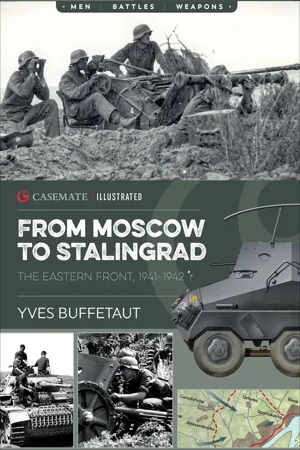

About this book

An account of the most crucial period of fighting on the Eastern Front, from the defeat of Germany at the gates of Moscow to their crushing loss at Stalingrad.

The path from Moscow to Stalingrad was littered with successes and losses for both the Red Army and the Wehrmacht, culminating in one of the harshest battles of the Second World War. Part of the Casemate Illustrated series, this volume outlines how it was that, less than a year after their defeat at Moscow, the German army had found a way to make the Soviet troops waver in their defense, with their persistence eventually leading to the Battle of Stalingrad.

The successful expulsion of the German troops from Moscow in the winter of 1941 came at a cost for the Red Army. Weaknesses in the Soviet camp inspired the Wehrmacht, under Adolf Hitler's close supervision, to make preparations for offensives along the Eastern Front to push the Russians further and further back into their territory. With a complex set of new tactics and the crucial aid of the Luftwaffe, the German army began to formulate a deadly two-pronged attack on Stalingrad to reduce the city to rubble.

In the lead-up to this, Timoshenko's failed attack on Kharkov, followed by the Battle of Sebastopol in June 1942, prompted Operation Blue, the German campaign to advance east on their prized objective. This volume includes numerous photographs of the ships, planes, tanks, trucks, and weaponry used by both sides in battle, alongside detailed maps and text outlining the constantly changing strategies of the armies as events unfolded.

"The wonderful photos and illustrations make this book entertaining." — New York Journal of Books

The path from Moscow to Stalingrad was littered with successes and losses for both the Red Army and the Wehrmacht, culminating in one of the harshest battles of the Second World War. Part of the Casemate Illustrated series, this volume outlines how it was that, less than a year after their defeat at Moscow, the German army had found a way to make the Soviet troops waver in their defense, with their persistence eventually leading to the Battle of Stalingrad.

The successful expulsion of the German troops from Moscow in the winter of 1941 came at a cost for the Red Army. Weaknesses in the Soviet camp inspired the Wehrmacht, under Adolf Hitler's close supervision, to make preparations for offensives along the Eastern Front to push the Russians further and further back into their territory. With a complex set of new tactics and the crucial aid of the Luftwaffe, the German army began to formulate a deadly two-pronged attack on Stalingrad to reduce the city to rubble.

In the lead-up to this, Timoshenko's failed attack on Kharkov, followed by the Battle of Sebastopol in June 1942, prompted Operation Blue, the German campaign to advance east on their prized objective. This volume includes numerous photographs of the ships, planes, tanks, trucks, and weaponry used by both sides in battle, alongside detailed maps and text outlining the constantly changing strategies of the armies as events unfolded.

"The wonderful photos and illustrations make this book entertaining." — New York Journal of Books

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Moscow to Stalingrad by Yves Buffetaut in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The fierce pursuit of their counteroffensive caused the Soviets such heavy losses at the beginning of 1942 that, by spring, the Wehrmacht found itself once again in a state of materiel superiority. Certainly, the Russians still had a considerable number of tanks, but the units were disorganized and unprepared for combat. On the other side, the Heer had new materiel, such as this Sturmgeschütz 40 Ausf. F of which the first examples appeared in 1942. (Bundesarchiv)

The Wehrmacht Prepares

The 1942 German offensive is of upmost importance in the history of World War II, as it was the first entirely directed by Adolf Hitler himself, after von Brauchitsch’s dismissal during the battle of Moscow.

The undeniable success of the defensive battle fought during the winter after the defeat outside Moscow convinced Hitler that he had a greater gift for the art of war than any—or indeed all—of his generals. Naming himself commander-in-chief of the Heer (German army), the Führer totally transformed the way the general staff worked. The time for testing future operations through Kriegsspiel (simulations or war games) was over—from now on, the Führer would give precise orders that the army were obligated to carry out. Nonetheless, the generals continued to attempt to influence Hitler’s decisions.

In January 1942, morale within the OKH was at its lowest. It was at this time that General Günther Blumentritt (so useful to historians thanks to his extensive memoirs) joined the Heer’s general staff, replacing Paulus. He wrote:

Kharkov was the objective of General Timoshenko, who wanted to beat the Germans by attacking first. (Bundesarchiv)

Several generals have declared that relaunching the offensive in 1942 is impossible, and that it would be wiser to guard properly that which has already been won. Halder was very hesitant on this question of resuming the offensive. Von Rundstedt was much more categoric and strongly advised that the German army retreat to the bases in Poland. Von Leeb agreed with him. Without committing themselves to such a radical solution, a lot of the generals worried where such a campaign would lead … But with the departure of von Rundstedt and that of Brauchitsch, the resistance to Hitler’s pressure—the pressure to resume the offensive—weakened considerably.

The departure of Generals Gerd von Rundstedt and Walter von Brauchitsch did indeed impact the remaining generals’ resistance to the Führer, but it was not the only factor: the failure of the Soviet counteroffensive to crush the Heer surely had an influence too.

The Priorities of the German Generals

It is often said that history is written by the victors. Yet this is only partially true; it might be more accurate to say that history is written by the survivors. In the case of World War II in general and the German army in particular, the survivors were the generals who, in their memoirs, criticized Hitler relentlessly (a task made immeasurably easier by his death) to distance themselves from the Nazi regime after its true nature was revealed in 1945.

In 1941 and 1942, when Hitler took definitive control over the armed forces, it could be said that he had an altogether clearer vision for them than did their generals. The latter, after their misadventure in Moscow, advocated a strategy of limited objectives, aiming towards the defeat of the Red Army, but not to conquer the Soviet Union completely—that would be far too risky. However, the United States’ entry into the war meant that the Axis forces had to act quickly, before the now strengthened Allies made any chance of success impossible. This the Japanese admirals understood in 1942, when they tried several times to stop the American fleet in the Pacific. Hitler was on the same page when he decided to launch a new general offensive in the East, to defeat the Red Army, to conquer the oil fields in the Caucasus and to crush the USSR, after which he would—as he told his generals—turn his attention westwards.

The German generals did not seem to have major strategic views; they were obsessed with the balance of forces in the East. It’s fair to say this was not very encouraging, but once again, when Germany re-engaged on the Russian Front, the armed forces had no choice but to win quickly or lose everything.

In November 1941, the OKH intelligence service, directed by Eberhard Kinzel, indicated that contrary to previous reports, the Red Army, by May 1942, would be able to re-equip no fewer than 150 infantry divisions, 30 cavalry divisions, and several armored formations, who would be given British and American tanks. In December, Kinzel estimated the number of infantry divisions facing the Wehrmacht in Russia at 200, not including the 40 armored brigades and 35 cavalry divisions. The Germans were evidently surprised by the Russians’ ability to rebuild and rearm.

This did not give Halder, chief of staff of the Heer, much confidence and he—as he had the previous year—butted heads with Hitler several times. Before a definitive decision was made, the two men came to an agreement on two preliminary operations: first, the retaking of the Kerch Peninsula and the capture of Sevastopol, and second, the reduction of the Izium salient threatening Kharkov.

General von Manstein commanded the Eleventh Army in the Crimea, with remarkable success. He swept through the peninsula before attacking the fortress of Sevastopol. He is pictured here, in the center of this photograph, with his left hand on his knee, during the siege of the port. Von Manstein was called upon to take an increasingly important role on the Eastern Front after the disaster at Stalingrad. (Bundesarchiv)

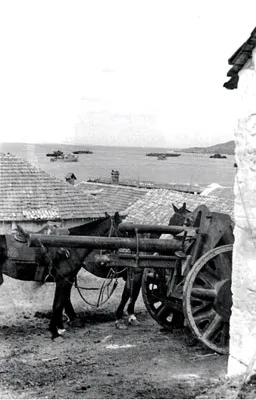

The Germans used many large flat-bottomed barges on the Crimean Front. Each was equipped with powerful Flak canons. (Bundesarchiv)

Two typical ships from the German flotilla in the Black Sea: on the right, an R-Boat alongside a Fährpram. Very large and thus very stable, the Fährpram carried an important load. (Bundesarchiv)

Romanian and German troops land on the Kerch Peninsula. The soldiers in the foreground are from Romania; those from Germany are on the Fährpram behind. (Bundesarchiv)

Success at Kerch

The first of Germany’s preliminary operations was undertaken against Kerch. Von Manstein’s Eleventh Army managed to regroup six German divisions and three Romanian divisions for the attack; the Luftwaffe in the sector was reinforced by Richthofen’s VIII Air Corps, bringing the totals to 11 Kampfgeschwader (bomber), three Stukageschwader and seven Jagdgeschwader (fighter) wings.

The Russians were far greater in number, and had lined up three armies—the 44th, the 47th, and the 51st—but their defenses lacked depth, and their first line was crushed by aviation and artillery on the first day of the assault, May 8, 1942. The first breach was only five kilometers wide, but the Soviets were unable to close it, and the Germans got a foothold to their rear thanks to the surprise arrival of light armored elements.

On May 12, the battle was virtually won, and on the 15th, the Germans entered Kerch. Some Russian soldiers were able to flee to the Kuban, but they left behind all their equipment, and the spoils were considerable: 170,000 prisoners, 1,100 guns, 250 tanks, 3,800 trucks, and 300 planes.

The Germans only lost 7,500 men and the Russians had shown a great tactical weakness, the defenders at Sevastopol remaining inert despite only facing second-order Romanian troops. It is interesting that at around the same time, on the northern front, a Russian offensive launched by two Siberian divisions commanded by General Andrey Vlasov, considered by Stalin to be one of his best generals, ended in bitter failure due to a lack of reserves and the obstinacy of the Stavka in ordering the offensive to continue when all was lost. Vlasov was surrounded and refused to get on the aircraft that would save him, as he would not abandon his men. Held prisoner with his general staff, he ended up defecting to the enemy and established an army of volunteers allied to Germany, the so-called ‘Russian Liberation Army’.

Operations on the Kerch Peninsula. In the foreground, a 105mm howitzer unloaded by the FH 18 a little earlier. In the background are several Fährpram, various ships and an R-Boot. (Bundesarchiv)

Ships of all types were used to land the last of the Russian troops. On the left is a real landing barge; on the right, a Danube pleasure cruiser looking rather the worse for wea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Timeline of Events

- The Russian Counteroffensive in the Southern Sector

- The Wehrmacht Prepares

- The German Plan

- Case Blau

- Towards the Caucasus

- The Advance on Stalingrad

- Afterword

- Further Reading