eBook - ePub

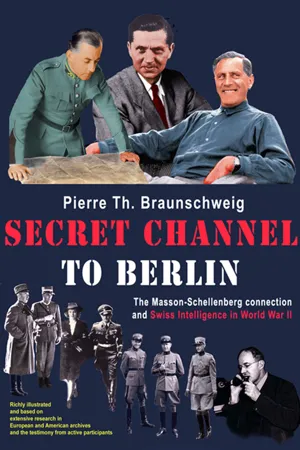

Secret Channel to Berlin

The Masson-Schellenberg Connection and Swiss Intelligence in World War II

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Secret Channel to Berlin

The Masson-Schellenberg Connection and Swiss Intelligence in World War II

About this book

A revealing account of Swiss intelligence operations during WWII, including a secret backchannel between Switzerland and Nazi Germany.

During World War II, Col. Roger Masson, the head of Swiss Intelligence, maintained a secret link to the German Chief of Espionage, SS Gen. Walter Schellenberg. With access to previously inaccessible documents, including newly discovered material in American archives, historian Pierre Braunschweig fully illuminates this connection for the first time, along with surprising new details about the military threats Switzerland faced in March 1943.

During World War II, Switzerland was famous as a center of espionage fielded by Allies and Axis alike. Less has been known, however, about Switzerland's own intelligence activities, including its secret sources in Hitler's councils and its counterespionage program at home. In Secret Channel to Berlin, Braunschweig details the functions of Swiss Intelligence during World War II and sheds new light on conflicts between Swiss Intelligence and the federal government in Bern, as well as within the intelligence service itself.

During World War II, Col. Roger Masson, the head of Swiss Intelligence, maintained a secret link to the German Chief of Espionage, SS Gen. Walter Schellenberg. With access to previously inaccessible documents, including newly discovered material in American archives, historian Pierre Braunschweig fully illuminates this connection for the first time, along with surprising new details about the military threats Switzerland faced in March 1943.

During World War II, Switzerland was famous as a center of espionage fielded by Allies and Axis alike. Less has been known, however, about Switzerland's own intelligence activities, including its secret sources in Hitler's councils and its counterespionage program at home. In Secret Channel to Berlin, Braunschweig details the functions of Swiss Intelligence during World War II and sheds new light on conflicts between Swiss Intelligence and the federal government in Bern, as well as within the intelligence service itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Secret Channel to Berlin by Pierre Th. Braunschweig, Karl Vonlanthen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The “Masson Affair”

Masson’s Interview

ON SEPTEMBER 11, 1945, representatives of the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, France, and China began a series of meetings in London to hammer out a peace accord for Germany after its unconditional surrender. In Switzerland, these important diplomatic negotiations made the front pages of that country’s traditionally well-informed and foreign policy-oriented newspapers. At one point, however, the news from London was pushed into the background as a result of more pressing domestic news relating to the war. Federal politicians were assessing the experience of the Swiss military as it had coped with the world war that had raged at the country’s doorstep. The Swiss Army officially went off duty on August 20—and now that the threat was over, it had become time to deal with some lingering issues that could not be resolved during the war.

During the second week of parliament’s 1945 fall session, the National Council, Switzerland’s House of Representatives, discussed the Military Department’s annual report for the year 1944. More than 30 members of parliament from all parties spoke during the floor debate. The Bern-based Bund newspaper commented that “after six years of war, during which some great achievements but also quite a few psychological mistakes had been made,”1 the numerous speeches served to “bring tensions that had built up over time into the open and surmount them.”2

This easing of tensions did not have a lasting effect, however, as the Military Department was back in the headlines at the end of the second week of the session, when news reached the members of parliament “through the noon edition of their newspapers about an interview that was presented as sensational, which it was indeed.”3 On September 28, 1945, the London-based Exchange news agency carried an article titled “The Threat Switzerland Was Facing in 1943” that created a storm of indignation in the Swiss press. The article read:

London, Sept. 28 (Exchange)—The special correspondent of the Daily Telegraph in Paris reports that he had an interview with Robert [sic] Masson, whom he calls the Head of ‘Swiss Counterintelligence.’ Masson told the correspondent that in March 1943, the Germans had intended to attack Switzerland and annex it after finishing their campaign. He explained that Hitler had personally ordered that preparations be made for this “military and political campaign” and had a total of 30 special divisions deployed near the [Swiss] border.

Masson said that surprisingly the plan was abandoned after Walter Schellenberg, Himmler’s right-hand man and head of German Intelligence, had been able to convince Hitler during a General Staff meeting on March 19, 1943 that Switzerland was more useful as a neutral country than as an occupied country because it would better cover Germany’s southern flank. According to Masson, in the heated debate during that meeting, Schellenberg gave his word of honor that the Allies would face fierce resistance if they tried to infringe Switzerland’s neutrality; he said there was no doubt that the Swiss Army would take up its arms if Allied armies launched an attack on the Swiss Confederation. Masson explained that Hitler finally calmed down and heeded Schellenberg’s advice.

Masson assured the correspondent that Schellenberg was no fanatic Nazi and had serious doubts as early as 1943 whether Germany would win the war. Masson insisted that in certain respects Schellenberg had sided with Swiss Intelligence and cooperated with it to save the lives of several well-known French prisoners of war. In addition, Schellenberg supposedly stood up for de Gaulle’s niece, Genevève de Gaulle, and had [General Henri] Giraud’s family freed in April 1945.

Masson told the correspondent that at the same time that Schellenberg negotiated with the Swedish peace mediator Count Bernadotte in Northern Germany, Schellenberg’s 1st adjutant Hans Wilhelm Egger [sic] traveled to Vienna to prevent the local SS there from carrying out Hitler’s orders. He explained that after Germany’s capitulation, Schellenberg had to return from Sweden to the Reich, from where he was transferred to London.4

The following day, Der Bund reported that the Swiss who had granted the interview was Roger Masson, “a colonel-brigadier who was Assistant Chief of Staff during wartime duty and Chief of Intelligence and Security. Hence, the information comes from someone who is in a position to know the facts.”5 The newspaper initially did not comment on the explosive content of the agency report but contented itself with expressing its annoyance about the Federal Council’s6 delay in informing the public in Switzerland about the threats the country had had to face during the years of the war. It said that because of this delay the public had to find out indirectly, through a foreign agency report, what a dangerous situation Switzerland had escaped, adding, “Once again the thorough Swiss have been put behind by busy foreign publicists.”7

The reactions were vehement all the way from conservative newspapers such as the Neue Zürcher Zeitung to the leftist press such as Vorwärts.8 However, the Swiss press was less indignant about the fact that it had “been cheated by a foreigner out of publishing this important information first”9 than about the fact that it was Colonel-Brigadier Masson—of all people—who had granted the spectacular interview. According to historian Georg Kreis, Masson had been ascribed “a not at all insignificant part”10 in imposing a strict censorship on the press during the war,11 explaining, “Even though press policy was not part of the tasks of [Masson’s] section per se, one of its duties consisted of procuring information about foreign countries and forwarding it to interested offices. As a consequence, the P.R.S. (Press and Radio Section)12 continuously received articles published by the German press or reports by the military attaché in Berlin or by Swiss who had informed Intelligence about their impressions upon returning home.”13 Concerning the Swiss press, Masson “fervently advocated remaining ideologically neutral and [at the same time] tirelessly supported the blood guilt theory”14; moreover, he was in favor of introducing pre-print censorship.15 Masson’s interview consequently had to be considered as particularly objectionable.16

In a first reaction, the Federal Council described Masson’s action “as tactless, to say the least.”17 The same day, it asked the military administration to look into the circumstances of the interview.18 The investigation inevitably uncovered details about the explosive relations between the Swiss and German Intelligence Services. However, Masson denied the accusation that he had disclosed secret information in the interview. He argued that in summer 1945, several months earlier, a book had been published in Zürich and Lausanne19 in which Swedish diplomat Count Folke Bernadotte reported Schellenberg as claiming that he had entered into contact with Swiss friends in order to prevent plans by Joachim von Ribbentrop and Martin Bormann to attack Switzerland from being carried out after they had been approved by Hitler. Masson’s conversation with the foreign journalist, which resulted in the “interview,” had actually revolved around the subject of Bernadotte’s book.20

In an extensive letter to Chief of the Swiss General Staff Louis de Montmollin, Colonel-Brigadier Masson explained how the contact with the journalist had come about and what they had discussed during their conversation.21 That letter is interesting not because of the extended publicity that the matter received at the time but because it is quite revealing about the character of the Chief of Intelligence. To a certain extent, Masson’s meeting with the American journalist Paul Ghali was a repetition of the circumstances surrounding his connection with SS Brigadier General Schellenberg that had come close to having disastrous consequences for him a few years earlier. He incontestably acted out of good intentions, once again trying to correct the wrong image that he thought foreign countries had of Switzerland; however, he forgot that even if he was most certainly qualified to do so through his position in the military, most likely he acted without having a political mandate.

Paul Ghali, a Paris correspondent for the Chicago Daily News whom Masson described as “a former comrade,” used to live in Bern for several years, where the two men had met.22 On September 21, 1945, they ran into each other23 in Bern when Ghali was back in Switzerland for a short visit. Masson explained to Montmollin:

Since I considered that what he had to say was always interesting, I once again spoke with him about several issues dealing with the recent conflict and the current international situation.… At a certain point during the conversation—I think that we were talking about the impression Americans who are on leave here have of our country— Ghali said to me that it was regrettable that the United States did not know more about Switzerland, in particular about its delicate situation during the war, and that it might be desirable to publish something on that subject.… When he mentioned Schellenberg again, Ghali told me that in France one knew that it was due to this irregular connection that we had been able to get some French, American, and English citizens freed. I told him no secret when I replied that I had indeed had the opportunity to meet with [Schellenberg] on three or four occasions exclusively in the interest of my country… and indirectly even in the interest of the Allies (repatriation of prisoners, etc.).

At the American’s repeated request, under the condition that the text would not be disseminated in Europe, Masson agreed to submit to the Chicago Daily News a note for the press on that issue. Ghali accepted Masson’s condition. Masson continued his explanation by stating, “As a precaution, I asked him to draft a text that he should submit to me for approval. But Ghali had to leave for Geneva, and the following day he was in Paris.” As Masson had no opportunity to look over the article, he began to have doubts, explaining, “The ‘conversation’ I had with [Ghali] could be interpreted in a wrong way. I telegraphed to him in Paris on 27 September, asking him to put off publishing his text.” However, there is written evidence that the message was returned to the sender, stating, “address unknown.” The following day, Masson was shocked to find out that the Exchange news agency had distributed to newspapers in Switzerland excerpts of Ghali’s uncorrected article from the United States. Masson immediately called Gaston Bridel, the Editor-in-Chief of the Tribune de Genève and President of the Swiss Press Association, to ask him to intervene with the agency to hold back the article. However, it was too late to do so.

The mutilated text that the London-based Daily Telegraph and the Exchange news agency published of the original U.S. article24 was clearly aimed at “creating a stir,” as Masson put it. In his letter to Chief of the General Staff Montmollin, Masson protested that the agency report misstated the facts, explaining:

I never said that Schellenberg was Himmler’s “right-hand man.” He was one of his many aides.… I said that Schellenberg was a friend of our country and that in my opinion, in March 1943 he had done everything he could to make clear to the OKW [German Armed Forces High Command] that it could have confidence in our willingness to defend ourselves against anyone. At that time, one of [Germany’s] main arguments for planning to take preventive action against us was the fact that “it did not trust our attitude” and believed that we would forsake our neutrality in favor of the Allies as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

Concerning the contacts that Swiss Intelligence had entertained with the SS Brigadier General and that the public found out about through the “interview,” Masson solemnly declared...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The “Masson Affair”

- 2. The Tasks and Characteristics of an Intelligence Service

- 3. The Structure of Swiss Army Intelligence

- 4. The French Bureau—Allied Section

- 5. The German Bureau—Axis Section

- 6. The Initiator of the Connection

- 7. Early Stages of the Masson-Schellenberg Connection

- 8. Extending the Connection: Masson Establishes Contact with Schellenberg

- 9. General Guisan’s Involvement in the Connection

- 10. Test Case for the Connection: The Alert of March 1943

- 11. Assessment of the Connection

- 12. Epilogue

- Notes

- Available Source Material

- Bibliography

- List of Abbreviations