- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

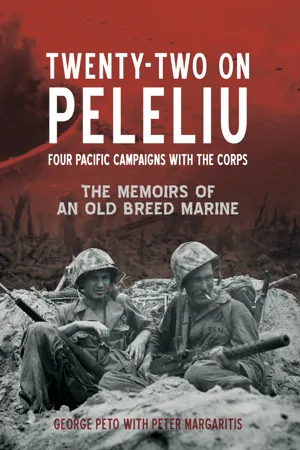

About this book

A memoir of a tough childhood—and tough combat—by an "adventurous, lively, outspoken, opinionated" WWII Marine veteran (

Columbus Dispatch).

On September 15, 1944, the US First Marine Division landed on a small island in the Central Pacific called Peleliu as a prelude to the liberation of the Philippines. Among the first wave of Marines that hit the beach that day was twenty-two-year-old George Peto.

Growing up on an Ohio farm, George always preferred being outdoors and exploring. This made school a challenge, but his hunting, fishing, and trapping skills helped put food on his family's table. As a poor teenager living in a rough area, he got into regular brawls, and he found holding down a job hard because of his wanderlust. After working out west with the CCC, he decided that joining the Marines offered him the opportunity for adventure, plus three square meals a day—so he and his brother joined the Corps in 1941, just a few months before Pearl Harbor.

Following boot camp and training, he was initially assigned to various guard units until he was shipped out to the Pacific and assigned to the 1st Marines. His first combat experience was the landing at Finschhaven, followed by Cape Gloucester. Then as a Forward Observer, he went ashore in one of the lead amtracs at Peleliu and saw fierce fighting for a week before the regiment was relieved due to massive casualties. Six months later, his division became the immediate reserve for the initial landing on Okinawa. They encountered no resistance when they came ashore, but would go on to fight on Okinawa for over six months.

This is the wild and remarkable story of an "Old Breed" Marine—his youth in the Great Depression, his training and combat in the Pacific, and his life after the war, told in his own words.

On September 15, 1944, the US First Marine Division landed on a small island in the Central Pacific called Peleliu as a prelude to the liberation of the Philippines. Among the first wave of Marines that hit the beach that day was twenty-two-year-old George Peto.

Growing up on an Ohio farm, George always preferred being outdoors and exploring. This made school a challenge, but his hunting, fishing, and trapping skills helped put food on his family's table. As a poor teenager living in a rough area, he got into regular brawls, and he found holding down a job hard because of his wanderlust. After working out west with the CCC, he decided that joining the Marines offered him the opportunity for adventure, plus three square meals a day—so he and his brother joined the Corps in 1941, just a few months before Pearl Harbor.

Following boot camp and training, he was initially assigned to various guard units until he was shipped out to the Pacific and assigned to the 1st Marines. His first combat experience was the landing at Finschhaven, followed by Cape Gloucester. Then as a Forward Observer, he went ashore in one of the lead amtracs at Peleliu and saw fierce fighting for a week before the regiment was relieved due to massive casualties. Six months later, his division became the immediate reserve for the initial landing on Okinawa. They encountered no resistance when they came ashore, but would go on to fight on Okinawa for over six months.

This is the wild and remarkable story of an "Old Breed" Marine—his youth in the Great Depression, his training and combat in the Pacific, and his life after the war, told in his own words.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Twenty-Two on Peleliu by George Peto,Peter Margaritis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Militärische Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Early Life

Neither of my parents was born in the United States. They both emigrated from Hungary. My father was born March 7, 1894, and Mom was born two years later. Pop could, more or less, speak seven different languages, so for one of his professions, he eventually became an interpreter for Municipal Judge Hunsicker1 in Akron whenever the accused could not speak English. Even though Pop spent many working days in a courthouse, he was mostly an outdoorsman, and my brothers and I picked up this trait. It was one that would shape a good part of my character.

I was the third of four children. The oldest was Elizabeth Rose, born six years before me on August 25, 1916. She was a somewhat thin brunette with a high forehead. I remember her as being sort of prissy, typical for a female in those days. Next in line was my older brother Alex, born July 25, 1920, in Trenton, New Jersey. A year after Alex was born, our family moved to Akron, Ohio. The next year, on September 18, 1922, I came into the world, born at home, with my mom assisted by a midwife. Soon after, our family settled on a backwoods farm in the Portage Lakes area south of Akron, and on June 2, 1928, when we lived in nearby Barberton, Ohio, younger brother Steve was born, mom assisted again by a midwife. That’s all poor folks like us could afford in those days.

My old man had a wild streak in him that in his youth often got him into trouble. Having a motorcycle sure as hell did not help. Nor did being an alcoholic. Yeah, as he grew older, he drank like a fish and smoked like a fiend. (Luckily, smoking was a bad habit that thankfully none of his sons ever took up, although unfortunately, Liz did.) In fact, Pop did so many things in his life the wrong way. Yet somehow, the old man lived to be 92 years old. Pop was a great contractor, quite the entrepreneurial self-employed builder. I mean, of just about anything. I remember in my youth that my brother and I would often go out with him and assist him in building a house, or a garage, or a fireplace or something. Sometimes, we dug basements for folks. Whatever we could do to make a buck, we would do.

Earlier in his life, my old man had trained to be a cobbler. In later years, on the east side of Akron, he started his own shoe repair store, selling and repairing shoes. Unfortunately, Dad gave up the trade, because he was not making much money at it. Also, in his mind, even an expert cobbler was a still lowly profession, not worthy of his own talents. So he decided to give up the store and become a freelance contractor. Mom couldn’t talk him out of his decision. In fact, she pretty much could not talk him out of anything. You just could not reason with him, especially when he was drunk. Anyway, Pop pretty much did as he damn well pleased.

And he could be one mean old bastard. Once when I was in grade school, I played hooky a couple times. I was hanging around the swamps with a friend of mine, Bob Rining, who lived down the street. Finally, my teacher, frustrated with me (as she often was), gave my sister Elizabeth a note to take home to my parents. Liz brought the note home and gave it to Pop, and he got mad as hell.

Determined to catch me in the act, he didn’t say a word to me when I came home that afternoon, and nothing happened to me that night. So the next day, unsuspecting, I skipped school again, and went down to the canal with Bob to take my beat-up canoe out for a ride. After a while, my father came down along the shore, spotted us, and stood on the bank, watching us idly paddling away, happy as a couple of larks. He did not even yell out my name: he just stood there, silent.

Finally, I looked up and saw him there glaring, and my heart skipped a beat. With a mean look in his eye, he wiggled his index finger, motioning me to come ashore. Taking a deep breath, we paddled over to the bank and got out of the canoe. Man oh man, that’s when all hell broke loose. He beat the crap out of me going up the bank and all the way back to our house, some three blocks away. That did the trick. No more skipping classes. I never missed a day of school after that. I was never easy to convince to do things, and normally, I often did things with little thought of the consequences if they were not hurtful or fatal to anyone. But this lesson took. Boy, did it take.

During these years, Alex and I often fished with dad at Wingfoot Lake. One thing that I vividly remember around five years old was seeing all these balloons floating around in the sky. They called them “airships,” but to me, they were big balloons. Most of them were those shorter blimps, although early on, we once in a while saw one of the huge, long dirigibles, like the German zeppelins. Before World War II started though, they stopped making those and were just making blimps. But because we lived so close to the Goodyear factory, we could clearly see the Akron blimp building from the lake. In the summer, you could see them flying around, and I swear, Goodyear must have had a blimp named for every month of the year. I’d just sit there in the boat or along the shore and stare at them. Once in a while, we’d see one of those big long dirigibles, like the Akron or the Macon. They’d glide on by, or sometimes hover near the ground as the ground crews worked to land them.

Life on our farm was primitive. We lived in a heavily forested area, with lakes, rivers, and swamps all around us. We were not far from the Ohio Canal, and we always kept a boat there that we used to go fishing or just exploring. We grew over half of our own food, and life as such was basic. For one thing, we had no indoor bathroom, and so going to the head in the wintertime was sometimes rather uncomfortable.

Country life like that was sometimes a challenge. For one thing we had bedbug problems. Not that this was unusual, because back then everybody in our area had bedbugs. My father though, was rather effective in controlling them. He just used a torch. It seemed to be an effective technique, and anyway, as poor as we were, we really had no alternatives. Chemicals for that sort of thing were not easily available back then; the only thing that you could buy came in powder form. That stuff was expensive, and anyway, it was not very effective against them.

Pop’s treatment was unique. Every month or so, he’d take our beds apart, and we would drag them outside. He would then separate the mattresses from the frames. The mattresses were filled with straw, so the remedy was easy. We would remove the old straw and burn it, while mom boiled the mattress covers. We owned a couple of blow torches, which were common back then. Each one was about 12 inches high, with a six-inch-round fuel tank. In it we would put gasoline or kerosene. Then he would pump up the blow torch, turn on the fuel valve, and light it. With a flame about a foot long, he’d take the torch and go to one corner of the bed frame, where it connected to the springs underneath. He would then go down the line of the bed springs and cook them little critters. And you could hear them sizzle and pop as he did. When he was done, he would then take the bed back inside, and we would be good for another month.

Because we lived as primitively as we did, we had to spend a good deal of time outdoors. Pop often took me and my two brothers out hunting for food. Rabbit was a common course for our meals. I had my own first kill when I was nine years old, and after that, I was never too content indoors. I inevitably became an avid outdoorsman, and so I never really acclimated to indoor activities. School, an indoor activity, was always difficult for me, because I preferred to go roaming through the woods looking for adventure, longing to just go exploring. Often, as a young teenager, I would get a friend to go with me and just take off to see what we could see. I took along any sort of basic road map and kept it in my back pocket. We walked wherever our curiosity took us, sometimes hitchhiking across the state by truck or by train. We sometimes stopped for the night on a hayloft or in a barn, before starting off for home the next day. It was a blast for me, and my curiosity always seemed to lead me to something new.

This outdoor nature of course had its drawbacks. As a teenager, it made my holding any job difficult. That was a big problem, because back then in the early thirties, jobs were difficult to land. However, I was an excellent hunter, and many was the time I would happily go out hunting with my dad for hours on end.

As I grew up, partly because of how we lived, I developed a positive attitude on life, and more often than not, I would not take things as seriously as sometimes the circumstances would dictate. I usually preferred the grin or the chuckle over the frown and the growl, and most of my teenage friends considered me to be more or less a happy-go-lucky fellow. So if someone got serious on me, I would laugh. Over the years, I found that this sort of lighthearted attitude was a double-edged sword. Sometimes it worked in my favor; certainly with the girls. Sometimes though, it backfired and worked against me; mostly with authority.

I remember one time when I was in the second grade. My teacher was this beautiful lady. I thought she was prettier than any gal I had ever seen, and I have to admit, I was smitten by her. We were studying a classic poem, A Tree, by Joyce Kilmer, and in the middle of it, somebody made a smart remark. Our teacher looked up from her book and sternly asked, “Who said that?”

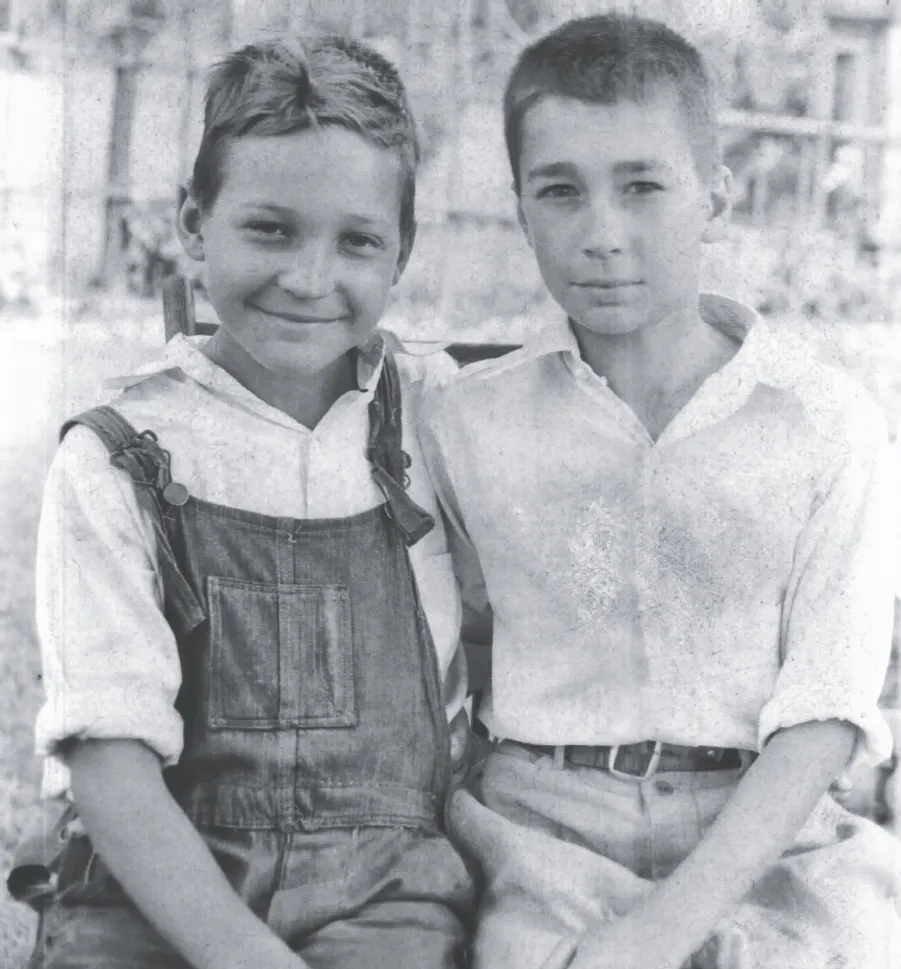

George (left) and Alex Peto as children, taken in around 1931. (Author’s collection)

The room was dead silent. She glanced around with a scowl, and started walking down the aisle, looking at everybody. She came to where I was sitting and looked at me. I was smiling.

She calmly concluded, “You’re the culprit.”

“No, ma’am. I’m innocent.”

But she didn’t believe me. We went on reading the poem. A little later, one of the boys in the back took a small wad of paper and threw it across the room, lightly hitting her in the back. She whirled around, now angry. The guilty party was openly defying her. “Who threw that paper?” she snarled.

Again, none of us said anything. She started walking up and down the rows of desks again, glaring. When she came to me, I just looked up and grinned at her. It had just struck me as being funny, and now I was trying to hide the grin by looking innocent. It backfired. She smacked me hard on the head. I saw stars.

By 1928, we had sold our first home and had twice moved away from the development sections. Now, we had moved into an area below Akron that was called the Portage Lakes, which included some eight lakes in the area. Living there, we were right next to the Erie–Ohio Canal. There were several reservoirs in the area that helped supply the canal, so water was always nearby.

In one remote area, there was a small dirt lane that went far back and eventually ended in an open area next to a swamp. The older kids used it as a lover’s lane. The main road that goes south in that area, State Route 93, is called Manchester Road.2

We lived on a simple, beat-up farm near Nesmuth Lake3 (we called it “Mud Lake”) on the north side of Carnegie Avenue, the only crossroads in the area. Back then, the area was open country, with swamps all over the place. There was no civic development, and there were no paved highways; just dirt roads with pylon street markers, and some pretty maple trees alongside our road. We got some livestock that we took care of: a horse, some pigs, and even a cow. Our house was next to a swamp, and there was a drainage ditch nearby. Dad and I built a small shelter over it for some ducks I had caught.

It was around that time when I became aware of the fact that the old man had become a bootlegger. I remember the time, because I was supposed to have started school that year, but I did not.

From the time I was born until the time I joined the Marines, we lived on several different farms in south Akron, all in a five-mile radius. We did not stay too long in any location, and we had to move a good deal, and that was for one good reason: the rent would come due. My old man unfortunately seldom paid his bills, and paying the rent was an on and off thing for him. He would run up a debt, and then either could not pay or would not pay; so as a result, we sooner or later were forced to move.

I grew up making a number of friends. Probably the closest were the Getz brothers. There were three of them, just like there were three of us Peto brothers. Our two trios hung out a lot, often sitting at each other’s family dinner tables. We shared most everything, and promised that we would always stay in touch.

My close buddy was the middle brother, Melvin Forest Getz—we called him “Waddy.” The older one was named after their father, Seymour, so we called him “Danny.” The youngest was Warren; we called him “Boysee.”

Waddy was a little over a year older than I was, and the two of us got along great. As we grew to be teenagers, he developed a strong, muscular physique, one that he often bragged about. He had a right to, because he really was a tough son of a gun, a pretty rugged guy. As he grew older and bolder, he once in a while would go into a bar and start a fight by picking on the biggest guy. Once in a while he would lose and come out bloody and worse for the wear, but he always came out laughing.

I guess that I was in my share of brawls too. There was this one guy that I went to school with named Paul Dunlap. One day, he started bugging me, ordering me around. I kind of let it go, but the second day he pushed me around, I started getting mad, realizing what was going on. He was just out and out bullying me. The third day he started in on me, I’d had enough, so I let him have it. We started fighting, and after about five minutes of trading punches, to my surprise, he started laughing. Me, I was fighting dead serious, but I guess he wasn’t. We finally stopped, and we made up. We ended up being friends after that. Not good ones, and I never got to where I trusted him, but we respected each other.

Yeah, even as kids, we did a lot of fighting back then, partly because it was rough where we lived, and partly because that was one of the few forms of entertainment that we had. And boxing was not only condoned, it was often encouraged. There used to be carnivals or sporting events where boxing matches were set up, and you could enter for next to nothing to compete for prizes, which sometimes were sponsored by our schools.

We used to box a lot back then. Mostly it was for fun and to pass the time, sometimes just to get better at doing it. Remember, boxing was really popular back then, and tickets for a good boxing match would go for good money, just like folks today would pay a lot to see a good basketball game. So we would box at all these different places. There was one place in town that had a bar on the first floor, and upstairs they had a gym. So we would go there and box.

We would box at other places too. A number of grade schools and high schools had a Weona Club,4 and every Wednesday night, the school would have a dance, or a set of boxing matches. Often, we would go and just box. Hell, all you just needed was a pair of gloves and a ring. Or, we played basketball. All you needed was some sort of hoop and a ball that bounced. What equipment we didn’t have, we improvised. Just like hockey, for instance. For hockey sticks, we’d go down to the canal and find these big bushes growing along the banks. We would each find a thick branch that curved up and went out over the water, and we would cut it off. We would then take these wooden branches, dry them out, and then shape them with our knives into hockey sticks. And for a puck, we’d get an old tin can, put a stone in it, crimp the ends, and then beat it around. That was it.

In the spring and summer we played baseball. Again, just the basics. All you needed was an open field, something that passed for a glove, a bat or a stick, and something that could pass for a baseball or softball. There was this one big field near my house, and there was a path that went r...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- A Note from the Co-author

- Introduction

- 1 Early Life

- 2 Before the Corps

- 3 Marine

- 4 Into Combat

- 5 Peleliu

- 6 Recovery

- 7 Okinawa

- 8 After the War

- 9 Old Friends

- Postscript

- Epilogue

- Sources