- 442 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

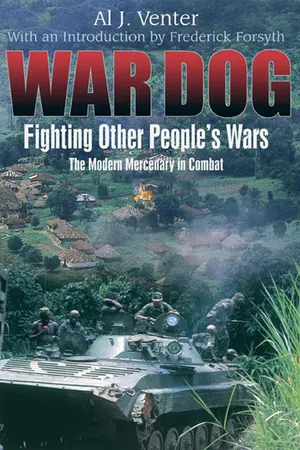

Mercenaries have been with us since the dawn of civilization, yet in the modern world they are little understood. While many of today's freelance fighters provide support for larger military establishments, others wage war where the great powers refuse to tread. In War Dog, Al Venter examines the latter world of mercenary fighters effecting decisions by themselves. In the process he unveils a remarkable array of close-quarters combat action.

Having personally visited every locale he describes throughout Africa and the Middle East, Venter is the rare correspondent who had to carry an AK-47 in his research along with his notebook and camera. To him, covering mercenary actions meant accompanying the men into the thick of combat. During Sierra Leone's civil war, he flew in the front bubble of the government's lone Hind gunship—piloted by the heroic chopper ace "Nellis"—as it flew daily missions to blast apart rebel positions. In this book the author not only describes the battles of the legendary South African mercenary company Executive Outcomes, he knew the founders personally and joined them on a number of actions. After stemming the tide of Jonas Savimbi's UNITA army in Angola (an outfit many of the SA operators had previously trained), Executive Outcomes headed north to hold back vicious rebels in West Africa.

This book is not only about triumph against adversity but also losses, as Venter relates the death and subsequent cannibalistic fate of his American friend, Bob MacKenzie, in Sierra Leone. Here we see the plight of thousands of civilians fleeing from homicidal jungle warriors, as well as the professionalism of the mercenaries who fought back with one hand and attempted to train government troops with the other, in hopes that they would someday be able to stand on their own.

The American public, as well as its military, largely sidestepped the horrific conflicts that embroiled Africa during the past two decades. But as Venter informs us, there were indeed small numbers of professional fighters on the ground, defending civilians and attempting to conjure order from chaos. In the process their heroism went unrecorded and their combat skill became known only to each other.

In this book we gain an intimate glimpse of this modern breed of warrior in combat. Not laden with medals, ribbons, civic parades, or even guaranteed income, they have nevertheless fought some of the toughest battles in the post- Cold War era. They simply are, and perhaps always will be, "War Dogs."

AL J. VENTER has been an international war correspondent for nearly thirty years, primarily for the Jane's Information Group. He has also produced documentary television films on subjects from the wars in Africa and Afghanistan to sharkhunting off the Cape of Good Hope. Among his previous works are The Iraqi War Debrief: Why Saddam Hussein Was Toppled and Iran's Nuclear Option: Tehran's Quest for the Atomic Bomb. A native of South Africa, he is currently resident in the United Kingdom.

Having personally visited every locale he describes throughout Africa and the Middle East, Venter is the rare correspondent who had to carry an AK-47 in his research along with his notebook and camera. To him, covering mercenary actions meant accompanying the men into the thick of combat. During Sierra Leone's civil war, he flew in the front bubble of the government's lone Hind gunship—piloted by the heroic chopper ace "Nellis"—as it flew daily missions to blast apart rebel positions. In this book the author not only describes the battles of the legendary South African mercenary company Executive Outcomes, he knew the founders personally and joined them on a number of actions. After stemming the tide of Jonas Savimbi's UNITA army in Angola (an outfit many of the SA operators had previously trained), Executive Outcomes headed north to hold back vicious rebels in West Africa.

This book is not only about triumph against adversity but also losses, as Venter relates the death and subsequent cannibalistic fate of his American friend, Bob MacKenzie, in Sierra Leone. Here we see the plight of thousands of civilians fleeing from homicidal jungle warriors, as well as the professionalism of the mercenaries who fought back with one hand and attempted to train government troops with the other, in hopes that they would someday be able to stand on their own.

The American public, as well as its military, largely sidestepped the horrific conflicts that embroiled Africa during the past two decades. But as Venter informs us, there were indeed small numbers of professional fighters on the ground, defending civilians and attempting to conjure order from chaos. In the process their heroism went unrecorded and their combat skill became known only to each other.

In this book we gain an intimate glimpse of this modern breed of warrior in combat. Not laden with medals, ribbons, civic parades, or even guaranteed income, they have nevertheless fought some of the toughest battles in the post- Cold War era. They simply are, and perhaps always will be, "War Dogs."

AL J. VENTER has been an international war correspondent for nearly thirty years, primarily for the Jane's Information Group. He has also produced documentary television films on subjects from the wars in Africa and Afghanistan to sharkhunting off the Cape of Good Hope. Among his previous works are The Iraqi War Debrief: Why Saddam Hussein Was Toppled and Iran's Nuclear Option: Tehran's Quest for the Atomic Bomb. A native of South Africa, he is currently resident in the United Kingdom.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access War Dog by Al J. Venter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq continue to dominate the headlines. Concurrently, notable changes in the manner in which military events are unfolding elsewhere have taken place. Today, when some wayward African dictator becomes restless or a South American warlord fosters insurrection, the world’s major powers are more inclined to look the other way. They are too focused on tamping down the worldwide Islamic terror threat. The possibility that the Pentagon will dispatch forces to assist some troubled Third World government is much less likely today than it was in our pre-9-11 world. Just getting the USS Iwo Jima to assist with a regime change in Liberia in August 2003 was difficult. For the difficult times we live in, it was also unusual. Thus, where security has become an issue in maintaining stability in some farflung state, another solution must be sought. And since it was the Dogs of War that cleared the bramble patch in the old days, once again, it seems, it will be their job to instill a measure of order in such places when things begin to fall apart.

1

HELICOPTER GUNSHIPS IN SIERRA LEONE’S WAR

“For the mercenary is a simplistic fellow. Not for him the strutting parades of West Point, the medals on the steps of the White House or perhaps a place at Arlington. He simply says: ‘Pay me my wage and I’ll kill the bastards for you.’ And if he dies, they will bury him quickly and quietly in the red soil of Africa and we will never know….”

Frederick Forsyth, “Send in the Mercenaries,”

Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2000

Anybody on the wrong side of sixty who believes that he can contribute something by going to war in a helicopter gunship in one of the most remote corners of the globe has got to be a little crazy. Or he’s into what aficionados like to term “wacky backy.” In my case, neither condition applies.

For five hectic weeks in the summer of 2000 I did exactly that, flying combat in West Africa with a bunch of mercenaries against rebels trying to take over the country of Sierra Leone. Although I was shot at as often as the others, my role was not as a combatant. Officially I was an observer, reporting for various publications in the stable of Britain’s Jane’s Information Group, including Jane’s International Defence Review as well as Jane’s Defence Weekly. In doing this, I was strapped into the gunner’s seat just ahead of the pilot on a rickety old Russian-built Mi-24 that leaked when it rained.

The commander of that bird was Neall Ellis (whom we affectionately called Nellis). We had flown together twenty years earlier during the bloody Angolan War. In those days he flew a French-built Alouette helicopter, the same type of gunship that had played such a significant role at Cuamato, a small town inside Angola that witnessed the hard hand of war from both the ground and the sky. In those days the gunships were flown by people like Arthur Walker and Heinz Katzke. These aviators made a name for themselves in a conflict that escalated several notches beyond a simple counterinsurgency. Their goal was to oppose the aggressive activities conducted by communist forces led by Fidel Castro’s Cuban Army and Air Force. The operations in that remote southern African theater took the form of irregular battles that one rarely read about in news reports of the day.

The fighting in Sierra Leone was different—and much more so after the turn of the millennium. Every day of the week, Sundays included, we’d fly one or more strike missions a day, taking the gun-ship sometimes deep into the jungle interior of a country roughly the size of Ireland. Other times we’d strike at targets not far from the capital Freetown itself.

The war was especially brutal on the ground where most of the victims were innocents. Aloft, we were the masters and it stayed that way as long as a batch of white-painted United Nations helicopters that had arrived a short while before I got to Freetown had not yet been armed. A fully equipped squadron of the more potent Indian Air Force Mi-24 variants that eventually became part of the UN detachment was still being assembled at Hastings, one of Sierra Leone’s smaller domestic airports, not far from the capital.

To paraphrase Shakespeare, our problems arrived in battalions. While the rebels attached to Foday Sankoh’s Revolutionary United Front (RUF) did not have an air force of their own, they made do with what they could cadge from those who supported their cause. As we were to constantly observe from radio intercepts, there were a number of foreigners who backed Sankoh’s revolt and were not averse to using their more sophisticated hardware when it suited their purposes. An occasional Mi-8 flown by South African and Russian mercenaries would slip into Sierra Leonian airspace from Liberia, usually headed for rebel outposts in the northern part of the country.

The ostensible object of these flights was to haul men and material, but the real reason behind their presence was diamonds. Tens of millions of dollars in raw stones were being illegally mined under rebel supervision in the northern Kono region. The rebel-backed helicopter gunships zipped in and out of the country, fast and low, to snatch large diamond parcels. The existence of Sierra Leone’s precious stones was the primary reason Liberian President Charles Taylor provided the RUF with military support. A cunning and ruthless operator, Taylor—who had come to power after a lengthy civil war—had but one purpose in mind: helping the rebels to take Freetown. By doing so, all of Sierra Leone’s diamond fields would eventually have been under his control.

By any yardstick, flying combat in Sierra Leone was an experience. The rebels had the run of almost everything beyond Freetown. Also, it was accepted by everyone onboard that if we were shot down or forced to land behind enemy lines, we would probably not survive. With our weapons—including a pair of belt-fed GPSG machine guns—we would certainly have been able to keep going for a while, assuming, of course, that we would survive the initial impact. But we were under no illusion that beyond the confines of Freetown and its environs we would be in our adversary’s back yard. They would have had the additional advantage of numbers: the four of us, no matter how well-armed would hardly have been a match for a squad of guerrillas, no matter how badly trained or doped. Personally, had I been faced with the options of a fight or making a run for it, I would probably have taken the gap towards the Guinea frontier. Its most distant point—considering that Sierra Leone is only fractionally bigger than New Jersey—the trudge through the jungle could never have been more than a hundred miles: perhaps three or four days on foot. One tends to think about such things when flying over endless stretches of tropical forest when you have the prospect of what might be a pretty bloody confrontation ahead.

Certainly, each one of us was also aware that Ellis had a price on his head: at the time I flew with him it was a bounty of a million US dollars, though there was a little muted discussion in Freetown’s watering holes as to whether that meant dead or alive. Several reports subsequently claimed that the reward was actually double that. Travelling about with this war dog each day, to and from work and back home from the pubs and sometimes Hassan’s place, quite often very late at night was probably a bit of a risk, but the truth is, nobody ever gave us more than a passing glance.

During the course of dozens of operational flights we saw a good share of action, with Nellis and the boys doing the necessary each time we encountered rebels. Through it all, we were lucky. Our worst afflictions during this period were mild bouts of malaria.

In retrospect, the Sierra Leone experience was neither as odious nor as repulsive as I might have expected, even though, on a day-to-day, sortie-by-sortie basis, we were able to account for sizable numbers of the enemy. It is also true that none of us felt anything for those who came into our sights, if only because Nellis was eliminating the same bloody cretins who were systematically mutilating children. In this regard, it was telling that when we’d return to Freetown after a flight and the people asked us whether we’d been successful, they would embrace us no matter how we answered. Each one of them was aware of the dreadful stories that emerged each day from the jungle that encroached to the edges of this huge suppurating conurbation.

It was that kind of war. And for two years, Nellis’ lone helicopter gunship was about all the majority of the population had on which to precariously pin their hopes.

By the time that I became involved, the ground war had been going on for several years. Casualties had been heavy on both sides, sometimes with a Nigerian Army-backed “peacekeeping mission” (ECOMOG) providing support, sometimes not. We had little doubt about the nature of the enemy. As one UN observer succinctly explained in an off-the-record briefing, “The majority of the rebels are mindless cretins who make a fetish of cutting off the limbs of children.” He went on to declare the rebels “simple-minded bastards,” some of whom, he explained, believed that such actions were appropriate when they needed to amuse themselves during a slow day in the jungle.

Flying with Nellis could be a taxing experience, with some sorties that left us drained after only a couple of hours in the air. We had our moments, obviously, especially when we hovered over enemy positions or occupied towns after being told by British military intelligence (under whose auspices Nellis operated) that the rebels had deployed SAMs. Conventional anti-aircraft weapons, I was soon to discover, was the norm, but since recent events in Chechnya had demonstrated that this hardware was a match for anything more conventional forces could field, such occasions would marvelously exercise the imagination.

Occasionally we would return to base with a hole or two in our fuselage, though at least once the damage was self-inflicted. During an attack on one of the more active rebel towns to the east of Freetown, Hassan, our starboard side-gunner, swung his machine gun in too wide an arc and stitched a set of holes into the starboard drop tank. Fortunately it was empty. Had it not been—with us using tracers—the upshot of that little episode over enemy territory might have been different. Nor was it a lone occurrence. The pair of Mi-24 helicopters operated by Nellis and his pals for the Sierra Leone Air Wing was probably more often patched than any comparable choppers then operational in Asia, Africa or Latin America.

While the Air Wing’s day-to-day regimen was dictated largely by events in the field—much of it coupled to intercepts of enemy radio messages, which came into the special ops room around the clock—there was always something new happening at Cockerill Barracks. The headquarters of the Sierra Leone military was a large, futuristic-looking structure at the far end of a festering lagoon that fringed one of Freetown’s outlying suburbs. From there, the country’s only operational pilot flew from a single, heavily defended helipad on the grounds of this expansive military establishment that dated from World War II.

Most of the sorties launched during my own sojourn in Sierra Leone were routine, quick in-and-out strikes on specific targets. Still, things could get hectic. There were days when the crew went up three times in quick succession, occasionally timing the last mission to return just as the sun dipped below the horizon beyond Cape Sierra Leone on which much of this city lies.

On one of my early flights, we’d been ordered to scramble on short notice. Since I was the newcomer, Nellis relegated me to the back of the chopper with the side-gunners. I’d barely had time to shower and change, but I went aloft anyway in a T-shirt, jeans, and a pair of flip-flops. It was a bad decision. I spent much of that flight dodging chunks of sizzling hot metal as brass shell casings clattered onto my exposed feet from two very active general purpose machine guns (or in official British Army terminology, GPMGs). I should have known better because I’d been in a similar situation in Angola a few years before while covering that conflict with Executive Outcomes, a mercenary firm based out of Pretoria, South Africa. At the time we were in an Angolan Air Force Mi-17.

The bloodiest chapter of Sierra Leone’s brief post-independent history is now on record, but the war could easily have gone the other way. Because the government had been unprepared for any kind of conflict, hostilities from the outset tended to favor the rebels. It remained that way until a lightning deployment codenamed “Operation Palliser,” involving Britain’s Quick Reaction Force (QRF) pushed a powerful body of rebels into West Africa. Tony Blair’s government was serious about countering a military insurrection in what until the 1960s had been one of the jewels in the British Imperial crown.

The British strike force was initially composed of eight hundred men of the 1st Parachute Battalion Parachute Regiment, which was later replaced by a Royal Marine detachment. Additional support came from a variety of Royal Air Force and Royal Naval elements, including the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious as well as the helicopter carrier HMS Ocean. C-130 Hercules transport planes from RAF Lyneham, and RAF Tristars from 216 Squadron operating out of Brize Norton, were tasked to shift most of the combatants and lighter hardware, with much of it arriving by sea a month later.

With only a few hours’ advance notice, four RAF HC Mk2 Chinooks were flown in pairs more than 3,000 miles to Dakar, on the Atlantic coast of Africa. The epic deployment had set out from RAF Odiham, home of the British Chinook force. The crews of each of these giant helicopters were ordered to fly twenty-three hours within a thirty-six hour window of opportunity. In order to make this possible, the Chinooks were equipped with two 800-gallon Robinson internal extended-range tanks. Each aircraft had replacement crewmen from all three squadrons, each of whom assisted in some important way on what is now recognized as the longest self-deployment in the history of the RAF helicopter force.

From the beginning, just about everybody involved militarily in Sierra Leone knew they were up against an extremely aggressive insurgent group accustomed to meeting little if any resistance from government forces. However, when the war flared up again in late 1998 (there had been several earlier conflicts, one of which involved Executive Outcomes and South African mercenaries) the RUF quickly demonstrated that it was better trained and equipped than it had been in the past. Because of earlier results, Sankoh’s rebel army was motivated to achieve its single objective: the control by force of the entire country. The rebels’ combat ability was evident: they succeeded virtually every time they set out to capture a position held by Sierra Leone security forces. Within a month of initiating hostilities in 1998, Sankoh’s revolutionaries could go just about anywhere they wanted except the capital of Freetown.

Foday Sankoh’s twisted path to power as the head of the Revolutionary United Front meandered through several countries and spanned decades. The radicalized 1970s student leader served for a time as a corporal in the army and later as a television cameraman. His anti-establishment criminal behavior, however, landed him in jail. When he was freed, Sankoh fled with fellow Sierra Leonean exiles to Libya in the 1980s, where President Muammar Gadhaffi was busy spreading revolutionary instability by stirring up West African dissidents like Sankoh. Seething with anger against those with more wealth and anxious to lead his own rebellion, Sankoh crafted an alliance with Liberia’s Charles Taylor, who was planning his own internal coup. Taylor’s horrific eight-year uprising seized the presidency in neighboring Monrovia in 1998.

With the support of Charles Taylor, Liberia’s rogue president, Foday Sankoh had used the two years following a ceasefire—which the mercenary group Executive Outcomes had brought into effect—to totally revamp his revolutionary forces. During this impasse, President Gadhaffi provided generous material and financial support, and he obviously had reasons of his own for doing so. Other countries linked to the rebels were Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta) and, ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Map Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- PART I: A THIN LINE

- PART II: MAELSTROM IN THE JUNGLE

- PART III: THE RISE OF THE PROFESSIONALS

- Epilogue

- IPOA Code of Conduct

- Notes