- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

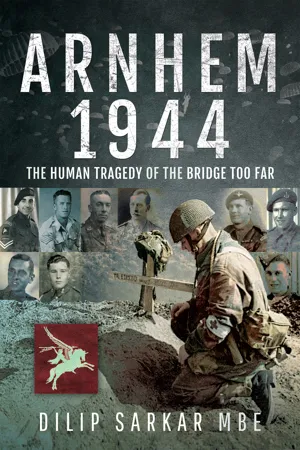

The airborne battle for the bridges across the Rhine at Arnhem ranks amongst the Second World Wars most famous actions inspiring innumerable books and the star-studded 1977 movie. This book, however, is unique: deeply moved, the author provides a fresh narrative and approach concentrating on the tragic stories of individual casualties.These men were killed at different junctures in the fighting, often requiring forensic analysis to ascertain their fates. Wider events contextualize the authors primary focus - effectively resurrecting casualties through describing their backgrounds, previous experience, and tragic effect on their families. In particular, the emotive and unresolved issue of the many still missing is explored.During the course of his research, the author made numerous trips to Arnhem and Oosterbeek, traveled miles around the UK, and spent countless hours communicating with the relatives of casualties achieving their enthusiastic support. This detailed work, conducted sensitively and with dignity, ensures that these moving stories are now recorded for posterity.Included are the stories of Private Albert Willingham, who sacrificed his life to save civilians; Major Frank Tate, machine-gunned against the backdrop of blazing buildings around Arnhem Bridge; family man Sergeant George Thomas, whose antitank gun is displayed today outside the Airborne Museum Hartenstein, and Squadron Leader John Gilliard DFC, father of a baby son who perished flying his Stirling through a hail of shot and shell during an essential re-supply drop. Is Private Gilbert Anderson, who remains missing, actually buried as an unknown, the author asks? Representing the Poles is Lance-Corporal Czeslaw Gajewnik, who drowned whilst escaping the hell of Oosterbeek, and accounts by Dutch civilians emphasize the shared suffering sharply focussed by the tragedy of Luuk Buist, killed protecting his family. The sensitivity still surrounding German casualties is also explained.This raw, personal, side of war, the hopes and fears of ordinary men thrust into extraordinary circumstances, is both deeply moving and revealing: no longer are these just names carved on headstones or memorials in a distant land. Through this thorough investigative work, supported by those who remember them, the casualties live again, their silent voices heard through friends, relatives, comrades and unpublished letters.So, let us return to the fateful autumn of 1944, and meet those fighting in the skies, on the landing grounds, in the streets and woods of Oosterbeek, and on the bridge too far at Arnhem.Now, the casualties can tell their own stories as we join this remarkable journey of discovery.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arnhem 1944 by Dilip Sarkar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Driver Robert Claude Bondy, 250 (Airborne) Light Composite Company, Royal Army Service Corps

For the inhabitants of Arnhem and Oosterbeek in the Gelderland area of the Netherlands, hard-by the river Rhine, Sunday, 17 September 1944, dawned like any other during those fearful days of Nazi occupation. Eight-year-old Wim ‘Willy’ van Zanten’s parents, Berend and Cornelia, ran a grocery store at 20 Cornelis Koningstraat, in the upmarket leafy suburb of Oosterbeek; that morning he walked with his mother down to the Old Church at lower Oosterbeek for the morning service. It was a perfect autumnal day, the church nestling amidst an idyllic setting: to the north the houses and woods of lower Oosterbeek, leading up to the Tafelberg Hotel, the Hartenstein mansion’s parkland, and the main Utrechtseweg, bisecting Oosterbeek and leading eastwards to the nearby city of Arnhem. To the south, a lush, green, water meadow – polder – between the church wall and Neder Rijn. To the east, a few hundred yards away, was a railway bridge crossing the river, and to the west wooded high ground, the Westerbouwing. It was a peaceful scene, except for one thing: increased Allied air activity.

The Old Church in lower Oosterbeek, in which Wim van Zanten and congregation worshipped that fateful Sunday of 17 September 1944. This house of God would later become the scene of bitter fighting. (Author)

The polder behind the Old Church, sweeping down the river Rhine; the church’s Sunday service was violently disturbed when RAF fighter-bombers attacked a German flak position here. (Author)

In the polder behind the church was a German flak battery – which suddenly disturbed the congregation’s singing when its guns started banging away. Today, Wim remembers that ‘I had to go to the toilet, which was next to the outside door, which was open due to the beautiful weather. I looked up into the blue sky at the very moment an RAF fighter dived and shot-up the German battery. Then there was silence.’

Kate ter Horst, at her lovely old former rectory home adjacent to the church, also remembered the attack:

The Ter Horst residence, the Old Rectory on Benedensdorpsweg, adjacent to the Old Church in lower Oosterbeek.

Amongst the amazed Dutch civilians rejoicing at this unprecedented aerial spectacle were Jan and Kate ter Horst. (Ter Horst Collection)

Suddenly a couple of fighters fly past. If only they would keep away with their tiresome noise, so low over our paradise . . . the baby cries out. Rikkatik-ketik! What’s that? The fighters bank. Rikkatik-ketik! They’re firing! Get inside! What a racket! Lower and lower they fly over the neighbourhood. Respecting nothing, they skim the very roof and we hear the sound of bullets hitting the slates . . . The planes keep flying outside and quite near us firing is continuing, while in the distance we can hear the sound of heavy explosions. Bombs? Is this an air battle? Father is on the roof with his oldest boy . . . they can see how the British fighters have hit the German Ack-Ack post behind our house. One piece is smashed and another is being dismantled; they’re leaving, they’re leaving!

This, though, was not some opportunist ‘armed-recce’ by 2nd TAF fighter-bombers – this attack was part of a large and complex air plan, paving the way for an unprecedented airborne landing. Throughout the preceding night, RAF Bomber Command had been busy, Lancasters bombed Luftwaffe airfields, and a combined Lancaster and Mosquito force attacked a dangerous flak concentration on the Dutch coast at Moerdijk. As Sunday dawned, 150 American 8th Army Air Force B-17 ‘Flying Fortress’ heavy bombers pulverised batteries around Nijmegen, on the mighty river Waal. 2nd TAF Mosquitos attacked roads, river crossings and barracks situated in Arnhem, whilst American 9th Air Force medium bombers plastered the mental hospital at Wolfheze – mistakenly believed to be in use as an enemy barracks (tragically causing fifty-eight fatal casualties amongst the innocent patients), and attacked ammunition stores in the surrounding woods. A number of Dutch civilians, in fact, lost their lives during the aerial bombardment of Wolfheze. Seventy-two years later, a Dutchman told me that ‘There were no German troops at the hospital or in Wolfheze. My grandfather was amongst the ninety-five civilian dead. We understand why this bombardment had to happen, mistaken though it was, but we have never had a “sorry”. We would still like one.’

Hawker Typhoons of 198 and 164 Squadrons shot up German flak batteries in and around Arnhem, firing lethal 60lb RP-3 ground-attack rockets and blasting away with 20mm cannon, destroying twelve such positions – including the gun behind the Old Church at lower Oosterbeek. Wim van Zanten: ‘In church the service continued and we sang “Een vaste burcht is onze God” (“A safe stronghold our God is still”), the service concluding with our national anthem. Mum and I left and crept home, running from house-to-house, as the RAF fighters were still in the air above us, shooting now and then.’ What happened next was astonishing.

Early that morning, in England, men of the 1st Parachute Brigade and 1st Air Landing Brigade had prepared for what remains the biggest aerial assault of all time. Whilst the three parachute battalions were to drop at Heelsum, their objective being Arnhem Bridge some eight miles distant, 2,900 men of 1st Air Landing Brigade were to be delivered by glider to fields around Wolfheze, whilst pathfinders of the 21st Independent Parachute Company dropped by parachute, tasked with marking the drop zone ready for the main parachute landing. The gliders involved were the Airspeed Horsa and the huge General Aircraft Hamilcar. The Horsa Mk I was a high-wing cantilever monoplane with a semi-monocoque fuselage, constructed of three sections bolted together, made of wood – wingspan 88ft, length 67ft, fully-loaded weight 15,250lbs. The front section housed the dual-control cockpit, the two pilots sitting side-by-side, and main freight-loading door; benches accommodated up to fifteen soldiers in the middle section, and supply containers could be stored beneath the wings. Fitted with a tricycle undercarriage, the two main wheels could be jettisoned in flight, the glider then landing on its belly. Once safely down, the rear section could be removed to facilitate rapid unloading of cargo, and a hinged nose section and reinforced floor accommodated the loading, carriage and unloading of light vehicles such as the ubiquitous jeep. On the Mk I, the all-important towing cable was attached via dual points on the wing, whilst, due to the extra weight imposed by vehicles the Mk II’s cable was shackled to the permanent nose-wheel oleo leg, although it remains debated whether this type was used at Arnhem. The gliders were flown by the very brave men of the Glider Pilot Regiment who piloted their unpowered craft to battle, towed by powered machines such as C-47 Dakotas and Short Stirlings. Cast off as the landing zone approached, the pilots essentially performed a controlled crash-landing. The glider pilots were considered ‘Total Soldiers’ who, after landing, were expected to deal with any military situation arising. These were special men indeed. Amongst those men en route to Wolfheze in a Horsa was Driver T/202762 Robert Claude Bondy of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC).

A jeep being loaded into a Horsa glider. The airborne RASC performed an essential function, including collecting and distributing air-dropped supplies.

Robert Bondy was born on 24 September 1908 (coincidentally I write this on 24 September 2016), and enlisted into the Territorial Army (TA) at Sutton on 6 June 1940 – two days after the Dunkirk evacuation, Operation DYNAMO, concluded and the tattered remnants of Lord Gort’s once proud BEF returned to England. It was a desperate time. A volunteer, giving his address as 306 Fulham Road, Fulham, London SW10, the 31-year old, who was 5ft 9in tall with brown hair and eyes, gave his nationality as ‘English’ and religion ‘Church of England’ and was declared ‘A1’ fit. He was a married man, having wed Ivy Humphrey at Brompton Parish Church on 14 January 1939, his occupation recorded as ‘Chauffeur’. Robert’s daughter, Pamela, born shortly before her father later flew to Arnhem:

A Horsa glider being towed off from a British airbase.

Paratroopers and gliders descending on the landing grounds near Wolfheze, 17 September 1944.

I know very little about my father’s life before he met my mother, although I believe that he was actually half Italian and one of eight children. ‘Bondy’ was an Anglicised name change, but I have no knowledge of the original surname and recently discovered that the family may even have been Austrian Jews. The eight Bondy children were raised in different circumstances, two being forced emigres to Canada. My father always told my mother that he had ‘nothing to tell’ about his family and not to ask again. My mother was a parlour maid and cook, at Guildenhurst Manor, Billinghurst, Sussex, the home of a Mr & Mrs Rogerson, whose money was in South African diamond mining, and my father was their chauffeur.

The RASC was responsible for land, coastal and lake transport, air despatch, barracks administration, the Army Fire Service, staffing headquarters units, supplying food, water, fuel and domestic materials, and the supply of technical and military equipment. It was an essential corps, in fact, supplying a mechanised army and keeping it on the move. As a chauffeur, Robert Bondy’s professional experience was directly relevant to his posting. Initially joining 31 Independent Infantry Brigade Company RASC, in December 1941, at Newbury race course, the unit then became 1st Airlanding Brigade Group Company RASC. In May 1942, the unit was re-designated 1st Airborne Division Composite Company RASC. Airborne warfare remained a comparatively new concept, and extensive training was required. Whilst the bulk of the unit existed to provide logistical support, three Parachute Platoons were tasked as their Brigade’s defensive platoon, and so were trained to fight as infantry soldiers. On 23 April 1943, Driver Bondy’s Army Service Record indicates another re-designation, this time to 250 (Airborne) Light Composite Company RASC, with which he embark...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Sophie Lambrechtsen-ter Horst

- Introduction: The Human Tragedy of the Bridge Too Far

- Glossary

- List of maps and drawings

- Prologue

- Chapter 1 Driver Robert Claude Bondy, 250 (Airborne) Light Composite Company, Royal Army Service Corps

- Chapter 2 Major Frank Tate, 2nd Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 3 Privates Thomas and Claude Gronert, 2nd Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 4 Lance-Corporal William Bamsey, Privates Frederick Hopwood and Gordon Matthews, 3rd Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 5 Lance-Corporal Ronnie Boosey, 1st Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 6 Trooper Raymond McSkimmings, 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron, Reconnaissance Corps, Royal Armoured Corps

- Chapter 7 Private Percival William Collett, 2nd (Airborne) Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regimen

- Chapter 8 Privates Gilbert Anderson and Harry Jenkin, 11th Parachute Battalion, and Private Gordon Best, 1st Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 9 Private Patrick Taylor, 156th Parachute Battalion, and Private Albert Willingham, 10th Parachute Battalion

- Chapter 10 Lieutenant Peter Brazier and Staff Sergeant Raymond Gould, Glider Pilot Regiment

- Chapter 11 Staff Sergeant Eric ‘Tom’ Holloway MM, Glider Pilot Regiment, and Lieutenant Ian Meikle, 1st Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Regiment of Artillery

- Chapter 12 Sergeant George Thomas, 1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Regiment of Artillery, and Sergeant James Sharrock, Glider Pilot Regiment

- Chapter 13 Sergeant Thomas Watson, 1st (Airborne) Battalion, The Border Regiment

- Chapter 14 Major Alexander Cochran and Private Samuel Cassidy, 7th (Galloway) Battalion, The King’s Own Scottish Borderers

- Chapter 15 Gunner Thomas Stanley Warwick, 1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Regiment of Artillery

- Chapter 16 Corporal ‘Joe’ Simpson, Lance-Corporal Daniel Neville, Sappers Norman Butterworth and Sidney Gueran – and survivor, Lance-Sergeant Harold Padfield, 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers

- Chapter 17 Squadron Leader John Phillip Gilliard DFC, 190 Squadron, RAF

- Chapter 18 Lance-Corporal Czeslaw Gajewnik, Signals Company, 1st Parachute Battalion, 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- Chapter 19 Gefallen: German Casualties at Arnhem

- Chapter 20 Flowers in the Wind

- Epilogue: Walking with Ghosts

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Other Books by Dilip Sarkar

- Plate section