eBook - ePub

First World War Uniforms

Lives, Logistics, and Legacy in British Army Uniform Production, 1914–1918

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

First World War Uniforms

Lives, Logistics, and Legacy in British Army Uniform Production, 1914–1918

About this book

View any image of a Tommy and his uniform becomes an assumed item, few would consider where and how that uniform was made. Over 5 million men served on the Western Front, they all required clothing. From August 1914 to March 1919, across all theaters of operations, over 28 million pairs of trousers and c.360 million yards of various cloth was manufactured.Worn by men of all ranks the uniform created an identity for the fighting forces, distinguished friend from foe, gave the enlisted man respect, a sense of unity whilst at the same time stripping away his identity, turning a civilian into a soldier. Men lived, worked, slept, fought and died in their uniform.Using the authors great-grandfather's war service as a backdrop, this book will uncover the textile industries and home front call to arms, the supply chain, salvage and repair workshops in France, and how soldiers maintained their uniform on the front line.Items of a soldiers uniform can become a way to remember and are often cherished by families, creating a tangible physical link with the past, but the durability of cloth to withstand time can create an important legacy. The fallen are still discovered today and remnants of uniform can help to identify them, at the very least the color of cloth or type of hob nail can give the individual his nationality allowing them to be given a final resting place.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access First World War Uniforms by Catherine Price-Rowe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Where’s My Uniform?

For centuries soldiers had marched into battle in brightly coloured uniforms to help identify friend from foe. As the nineteenth century progressed, it became clear that camouflage was becoming an ever more crucial factor. In Peshawar in 1846 the Corps of Guards were ordered to take white cotton cloth to the river bank, soak it in water then rub with mud to blend in with the local plains landscape.1 In 1848, Lieutenant William Hodson, Second in Command and Adjutant to the British Indian Army regiment the Corps of Guides requested a drab coloured uniform for the men to ‘make them invisible in a land of dust’.2 Khaki was born and its name was believed to come from the Hindu and Urdu word for something which was ‘earth’ or ‘dust’ coloured.3 Made from cotton drill, the uniform was ideal for tropical conditions but unsuitable in other climates, as the Boer War of 1899 - 1902 highlighted. Its inadequacies in the cold nights encountered on the South African plains meant a thicker, warmer fabric was needed.

‘Rank and File’ Service Dress

At the start of the twentieth century, all aspects of the British Army needed to modernise and uniforms were no exception. A single camouflaging colour for a universal uniform was conceived from bringing together the diverse colours of regiments and corps. Made from dyed thick wool serge fabric, the new style uniform debuted in 1901, with the approved pattern (design) ‘sealed’4 a year later and known as the 1902 Pattern Service Dress (Other Ranks (ORs)).5 Consisting of a tunic (jacket) and trousers, its manufacture was considered too expensive due to the coloured piping used to distinguish different regiments, corps, and services. The piping was removed and the revised design was approved and ‘sealed’ as the 1907 Pattern Service Dress (ORs).6 The only regiments to retain any trace of colour in the new pattern SD were Scottish, where the kilt tartan of the regiment was worn in conjunction with a khaki tunic. No matter their rank, everyone in the British Army now wore khaki7 in their daily work.

In 1914, the 1907 Pattern Service Dress was only seven years old and was supplied up to the outbreak of war. Although both ‘rank and file’ as well as officers wore khaki, the cloth was completely different, with the former made of a coarser wool that produced a strong, thick, durable cloth called ‘serge’, and the latter of a higher quality ‘Merino’ wool cloth called ‘Barathea’ that was a thinner and finer weave.

Other Ranks SD Tunic and Trousers (dismounted). Accurate Replica (Author’s Collection).

Service Dress Tunic (ORs): These were worn by all non-commissioned ranks of the army regardless of regiment or corps, as a single-breasted jacket that fastened up to the neck, ending in a high collar which rolled back. Brass monogrammed buttons known as General Service (GS) buttons had the Kings Crown embossed on them and were 1½” (3.81cm) in diameter. Five of these secured the jacket with two hook and eyes at the collar to hold it together. Two pleated pockets were positioned on the chest, with smaller ¾” (1.90 cm) GS buttons securing the flaps to the pockets. These smaller buttons also secured the flaps on the larger pockets that were positioned on the lower section of the jacket below the waistline. To give a smart look to the jacket, the lower pockets were on the inside with the flaps on the outside. Inside on the front right side, a small pocket was created that was large enough to carry a soldier’s field dressing.

Regimental brass shoulder titles were affixed to the shoulder epaulettes which were attached to the jacket with small GS buttons. Shoulder patches extended from the shoulder seam down the front ending just above the chest pockets, offering added protection against wear and tear when a rifle was used as well as webbing straps. The upper right sleeve between the elbow and shoulder bore the rank of the soldier, a Private wore nothing while chevrons made from cloth denoted non-commissioned officer (NCO) ranks. George was promoted several times throughout the war, first to Lance Corporal with a single chevron, then to Corporal with two chevrons before ending up as a Sergeant with three chevrons. For rank badges above that of Sergeant, there was a variety of crowns and laurels of which the highest non-commissioned rank was a Warrant Officer Class One. Furthermore, in some instances divisional insignia badges of cloth were worn on the sleeves above the rank; while on the left sleeve between the cuff and elbow, soldiers that had a specialist skilled job, such as a Farrier or Lewis Gunner, often wore a trade badge - in the case of a farrier a brass horseshoe and the Lewis gunner a brass ‘LG’ surrounded by a laurel wreath.

Later in 1916,8 a two inch (5.08cm) vertical gold-colour metal ‘wound stripe’ was introduced for soldiers wounded since 4 August 1914, and worn on the left sleeve between cuff and elbow.9 In addition, a Good Conduct Stripe was introduced as an inverted chevron for between two and four years ‘good service’ (i.e. no disciplinary record). In early 191810 ‘Overseas Service’ chevrons appeared and were worn on the right sleeve between the cuff and elbow. Consisting of small chevrons pointing towards the elbow, a red chevron indicated service on or before 31 December 1914, and a blue chevron for each full year (continuous or non-continuous) served overseas thereafter. Except for the wound stripe, all badges were made from a khaki cloth background embroidered with the design regardless of what they signified.

Service Dress Trousers (ORs): Sometimes described as dismounted trousers, SD Trousers were made from the same khaki serge cloth as the jacket and were designed to have a high waist with a V-shaped back which had changed little from the Victorian era.11 They were fastened at the front by brass buttons in a concealed fly - the ½” (1.27cm) four-holed buttons punched from brass sheets, and usually had the manufacturers name embossed on the rim. Soldiers in mounted regiments, such as Royal Horse Artillery, wore beige-brown riding breeches made from a thick wool cloth known as ‘Bedford Cord’, with leather patches reinforcing the inside leg against wear on the saddle. Scottish kilted regiments wore kilts depicting their regimental tartan, but instead of a standard khaki SD Tunic their jacket had the front hem edges cut back and rounded to allow for the wearing of a sporran. Operationally, khaki kilt covers were issued and worn over the kilt to provide camouflage.

‘V’ Shaped back of SD trousers with braces attached. Accurate Replica (Author’s Collection).

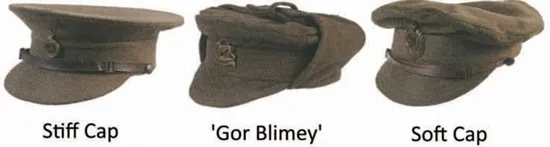

Service Dress Cap: A stiff cap (SD Model 1905) was issued decorated with the soldier’s brass regiment or corps badge in the centre above the peak and adjustable leather chin-strap. Made from khaki serge with a stiff peak and a crown held rigid by wire, the cap sat high on the head and gave little protection to the ears or back of the head in freezing weather.

During the winter of 1914 - 1915, a new cap was issued, to help alleviate manufacturing issues and protect against the cold. Made from flannel-lined khaki serge, but soft without a stiff peak or rigid crown, it was known as the Winter Trench Cap (Cap, Winter SD Model 1914),12 and had side-flaps to cover the ears in cold weather, and was secured by an adjustable chin strap. In fine weather, when not required, the flaps were raised up and secured over the crown of the cap. An added strip of fabric at the back could be folded down to cover the neck during wintry weather. The cap was floppy and popular with the troops due to its relaxed look and functionality, though its unmilitary appearance was not universally welcome. It soon acquired the nickname ‘Gor Blimey’, an exclamation (‘God Blind Me!) allegedly uttered by seasoned soldiers and sergeants upon seeing it.13

A ‘soft’ Trench Cap (Cap, Soft, SD Model 191614) based on the original stiff-peaked SD cap was introduced in early 1916. Removal of the wire in the crown and the stiff peak made the cap softer and was easier and cheaper to manufacture than the original Model 1905 SD cap. In December 1917, the standard soft ‘trench’ cap was revised, being made this time from a waterproof cotton material (gabardine) (Cap, Soft, SD Model 1916 / 1917).15

Cap SD Model 1905, Winter SD Model 1914 (commonly known as the ‘Gor Blimey’), and Cap Soft SD Model 1916 (From Tradition to Protection – British Military Headgear in the First World War. Anon: 2015 - By kind permission of Philippe Oosterlinck Collection, In-Flanders Field Museum, Ypres).

Cap Badge / Shoulder Titles: The cap badge identified the regiment or corps16 the soldier belonged too, and was worn in the centre of the headgear, with the shoulder titles mounted on the SD jacket epaulets. Predominately die struck (stamped or pressed out using a die), the cap badge was usually made of all brass, all nickel (white metal) or a combination of brass and nickel (bi-metal), whereas the shoulder titles were made of brass.

Shirt: Issued to soldiers since the mid-nineteenth century, the long-sleeved ‘greyback’ shirt was made from wool blue-grey flannel with a bib style buttoned half front that fastened to the neck in the same style of four-holed brass buttons as worn on the trouser. A ‘grandad’ collar17 enabled the shirt to lay flat under the high collar of the jacket and a small cuff with a button placket secured the sleeve at the wrist. With a strip of white cotton affixed to the front for the soldier to write his service number on, it was cut long so that it would stay tucked into the trouser as the soldier carried out his daily duties.

When the shortage of uniform items took hold, the Army’s Contracts Department was forced to buy civilian stocks of the same style of collarless shirt, making it common to see soldiers on parade in both military issued grey flannel as well as civilian white cotton pin stripe shirts.

Cap badge and shoulder titles for the Gloucestershire Regiment and Royal Engineers (Author’s Collection).

Grey Flannel shirt. Accurate Replica (Author’s Collection).

Puttees and B5 Ammunition Boot. Accurate Replica (Author’s Collection).

Ammunition Boot and Puttees: These are stereotypical items of uniform depicted in most images of ‘Tommy,’ but there was a sound rationale behind the short boot and puttee. Worn with short ankle-high brown/black18 B5 ammunition boots,19 not only did the puttee cover the gap between the top of the boot and trouser, thus preventing dirt and stones from entering the boot, but it also gave valuable support to the calves and legs when marching long distances. However, puttees needed to be worn correctly. The technique was to wind them tight enough as to not slip down, but not so tight that they restricted circulation; a factor recollected by Fred Wood who recalled the attempts of his fellow soldiers to tie them neatly: ‘Some chaps had them tied from ankles, others wound them round and round their calves like bandages. We were saved by an older man who had served in the Boer War, who showed us the trick…’20

The direction of the puttee wind varied too. Mounted regiments, such as the Royal Field Artillery, wound their puttees from knee to ankle with the knot of the binding tape on the outside of the leg, which prevented them from coming undone when rubbed against the saddle. Unmounted, such as infantry regiments, wound their puttees from ankle to knee, with the binding tape on the inside leg. This classic but simple difference gives a way of identifying whether a soldier was mounted or unmounted in old photographs.

Personal Equipmen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- British Military Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Modern Conflict Archaeology

- Introduction – Where It All Begins

- Chapter 1 – Where’s My Uniform?

- Chapter 2 – The Real ‘Material’ Culture

- Chapter 3 – Factory to Front

- Chapter 4 – Laundering the War

- Chapter 5 – Salvage and Recycling – Materials and Men

- Chapter 6 – Coming Home

- Chapter 7 – Finding George - The Afterlife of Military Clothing

- Appendices

- Family Research – Useful Websites / Information

- Places to Visit – Textile Heritage Today

- Bibliography

- End Notes