![]()

Part 1

Take-Off

“. . . have slipped the surly bonds of earth . . . and touched

the face of God”

(From the poem “High Flight”

by Plt Off J G Magee RCAF)

![]()

Chapter One

The Federation

A Black Moment

They came at me from low on the left, bright flashes out of the dark. I was bloody frightened, probably more so than ever before. It was a black night and the lights had all gone out, but all the time these numerous, vivid white flashes were coming languidly straight up at me. Regular winking specks always appearing to move lazily in my direction, but then astonishingly, at the last possible moment, veering off rapidly and whizzing through in a hurry of whirling motes, momentary darts of fire through that black night, zipping past and just missing with a final incandescent burst. These stunning white flashes were not good news, and I had no idea what the other three were up to or what they were thinking – one in front of me and two behind, diving into this unfathomable murk. That customary feeling of invincibility one felt when in a fighter cockpit had dissolved into something decidedly shaky.

This was no ordinary dive. It was just after dusk, three days after Christmas 1966, and I was at 12,000ft in a single-seat Hunter fighter over Awabil in the Radfan mountains of southern Arabia, extremely close to the Yemeni border. What was I doing at the time? 420 knots, and I’d just learnt the meaning of the phrase: ‘The fog of war’!

This was our first dusk scramble. As we took off, the afterglow of sunset had dissipated as it does in lower latitudes, and the dim of night had suddenly crept up on us. Diving now into 7,000-foot mountains at 30 degrees at night in a day-fighter plane, on the blackest night of the year, with 23mm tracer shells coming up and filling the windscreen, was not conducive to longevity. This remarkable, life-threatening event would be incomprehensible but for the fact that just before dusk a British Army patrol had been ambushed by a party of Yemeni dissidents. The patrol’s perilous condition required us to improve their life expectancy. I was No 2 in the four-aircraft formation responding to their crisis call, and we all certainly earned our flying pay that night!

Unfortunately, on arrival in the target area, the leader, Flt Lt Kip Kemball (now retired as an Air Marshal), called as briefed to switch off all our nav lights, and then throttled back as he tipped into his rocket dive. His lights and the glow from the back-end of his jet pipe went out, and abruptly all went impenetrably black. That hadn’t been briefed! I had nothing left to formate on, and couldn’t see the ground, the leader or anything, never mind any target. The only part of the universe moving outside the warm, red glow of the cockpit lighting was the white-hot tracer coming up lazily from below.

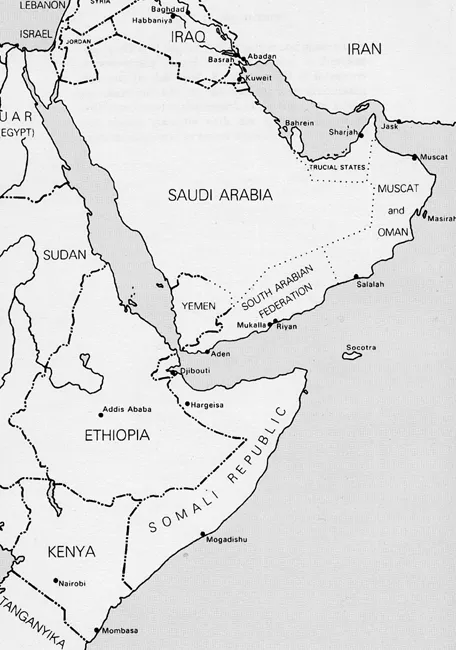

Fig 1. Position of Aden & The South Arabian Federation in the Middle East of 1965. ©CROWN COPYRIGHT/MOD.

With a flash of passion tipped with the courage of panic, I slanted in behind him. By now I was down to between nine and ten thousand feet with Kip just in front of me, having disappeared into the cold black night below, and the third and fourth aircraft just behind, diving in line astern, rapidly and steeply into the charcoal unknown only two thousand feet from the volcanic mountain tops. I had this panic thought: I’m not paid enough to do something so stupid as this, and whose bloody idea was it anyway? It was turning into one of those situations over which I had no control!

Yielding to a calmly normal, but irresistible impulse, an overwhelming desire for self-preservation, I decided it was time to get out of there in a hurry, so I screamed a radio warning and pulled like mad. It was then that I saw the fireballs of the first of the thirty-six rockets detonate as they hit the target area. Being young and rash, I decided to complete a timed circuit and go in behind No 4. After seeing 3 and 4’s rockets go off, I slotted temerariously back in behind them into the usual 30 degree dive and, still completely unsighted, pickled off my rockets and, with an enormous release of tension, headed for home.

These uncontrolled events had occurred in response to the usual army grievance, kicking up a fuss about no air support at night from the RAF’s dayfighter/ground attack squadrons. So someone with no day/night fighter experience decided that we ought to be able to do the job twenty-four hours a day: Christmas present 1966: do it at night!

Christmas 1966. I was twenty-one years old and I’d been serving in Aden for just under two years, playing my part in the downfall of British Empire. When I’d appeared at the top of the transport aircraft steps on my first arrival at RAF Khormaksar just to the North of the port of Aden, the wall of hot air hit me with stunning effect. After the initial heat shock, looking at the black mountains and bleak, green-less sand and dust landscape, I knew I had arrived in the Empire for the first time. It was an exciting but unsteady moment, and I felt a little shaky with trepidation, perhaps as seventeenth-century buccaneers did on making their first landfall on foreign territory ready for the plundering.

This is where my flying career took-off. I was joining the one RAF Squadron that could truly be called “The Empire Squadron”, having been policing the Middle East since the World War One. And I would soon discover that the British Empire – the biggest empire the world has ever seen – could be magically exotic, decadent, rich with strange places, perfumes and spices, and peopled by every class and creed of the deepest dye.

Seized from the Arabs in 1839 and ruled by the East India Company as a strategic coaling station serving ships trading between Britain and the Raj, Aden was transferred to the Crown in 1858. After the opening of the Suez Canal its importance increased. Latterly it contained the main BP Oil Refinery at Little Aden, a vital air-refuelling stop in the only British colony in Arabia.

Though Aden became a separate colony from the Indian Raj only in 1936, additional territory had been gradually brought under British protection, from 1873 onwards, through some ninety separate treaties with inland Arab sultans, forming the Aden Protectorates (renamed in 1963 the Federation of South Arabia). This was nothing more than a loose federation of independent states providing, inter alia, defence in perpetuity for those sultanates and sheikdoms. We were the law in Aden, but not in the protectorates unless requested. This interaction caused most of the ensuing problems and, as with Iraq, the area was too feudal, too medieval, and impossible to govern. The Federation stretched almost 1,000 miles from Aden in the south-west to the Dhofar region of Muscat & Oman in the north-east. As well as the border with Yemen, some of the Federation’s borders edged on southern Saudi Arabia, the empty desert quarter. Post World War II, AHQ Aden controlled some thirty small and widely scattered stations, including outposts on Kamaran Island in the Red Sea off the Yemeni port of Hudada, Perim Island in the mouth of the Red Sea, and Socotra Island off the Horn of Africa.

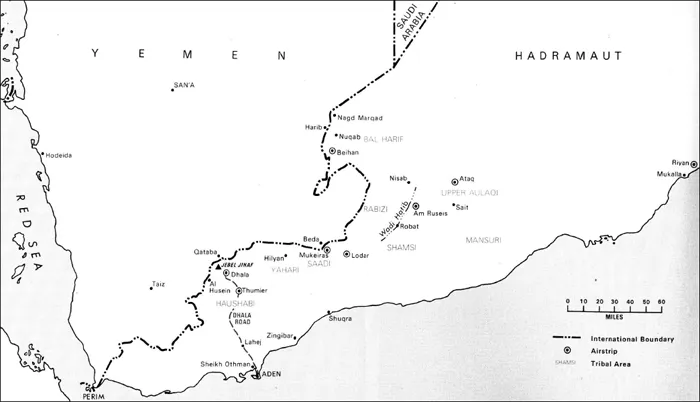

Fig 2. Aden and the Protectorates 1965. ©CROWN COPYRIGHT/MOD.

The RAF had come to Khormaksar in Aden, and No. 8 Squadron to the Middle East, in 1919 after the First World War. The Squadron (Sqn) arrived in Aden from Iraq in 1927, and stayed for the duration. As the RAF had been put in sole charge of governing the province and the Squadron was the primary instrument of power, the Squadron Commander was actually the head of the government at one time! The Aden Colony itself was the only territory in the whole Arab world under complete British rule, and the most politically and socially advanced state in the Arabian Peninsula. It was known as “The Little Raj”, with a cosmopolitan population in the early ’60s of 140,000, all living in reasonable prosperity and ruled by some 4,000 British government bureaucrats. Unlike in the wider Federation, order reigned in Aden, and no one walked the streets in fear, at least not until the 1960s.

Post-1946 efficiency measures reduced Air Forces Middle East Command (AFME) from 20,000 airmen with no squadrons to 7000 supporting thirteen by the 1960s.

RAF Khormaksar, the largest airfield in RAF history, supported 13 squadrons and independent flights in three flying wings (over 80 aircraft of 11 types), with two engineering wings and two administrative wings, sometimes three RAF Regiment Squadrons, a full Maintenance Unit, trooping flights from UK, and a civilian airport including Aden Airways main base. This huge jam-packed airfield with only one runway absorbed a hefty share of the seventy-five square miles of the Aden peninsula with some 6,000 airmen with 9,000 dependants, all there to police the Aden and the South Arabian Federation against terrorism and tribal uprisings.

In early ’65, “Aden’s Own1” 8 Squadron, part of our Strike Wing with a squadron of Shackleton maritime reconnaissance Bombers and two and a half Hunter Squadrons, was tasked both with army support and the air defence of the region. From an Egyptian and Russian-backed government in the Yemen actively supporting fiercely hostile and dissident tribesmen, over 100,000 square miles of rugged mountain and desert (with no red avoidance dots on the map!) were policed by this outfit. It was still a raw frontier area, a mini-version of the North West Frontier. These last raw vestiges of Empire proved the best grounding in fighter-flying anyone could desire with the finest low flying on active service.

This harsh terrain bred a hungry, isolated, savage people living in fortified villages, often on flat mountain tops, their ideas dominated by their rifles and their gambias (their traditional curved daggers), always to hand to guard their terraced fields and flocks from covetous neighbours. Sentinels manned rocky watchtowers ready to shoot approaching strangers on sight. Blood feuds were fought for generations, long after the original quarrel was forgotten, and populations were counted by the number of available armed men and boys. Not surprisingly, the inhabitants are some of the poorest in the world, with no natural resources and little water. Pot-shots from neighbours were a normal hazard of travel beyond village boundaries. It added passion to the hard life of survival in an environment cursed by nature.

The Aden Protectorate Levies (APL) – with air support from 8 Squadron – were trying to be umpires, keeping the war games within sporting limits, and occasionally they clashed with raiding tribesmen from Yemen, armed with ancient Turkish rifles. Two decades earlier, the RAF had bombed Taiz, one of the twin capitals of Yemen, but regular ground and air patrols to show the imperial flag had usually been sufficient to maintain the status quo. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, the situation was deteriorating. The nature of the age-old tribal disputes had subtly changed as the raiding parties replaced their Turkish arms with modern Czech rifles and machine guns, and were clearly under professional military direction – from the Egyptian army. Soon after his victory in the Suez War of November 1956, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser had launched his campaign against the British in Aden, sponsoring a New Year’s Eve, major incursion over the Yemen frontier with little or no reaction from London. Yet there was something of a dichotomy in operating modern, jet-fighter planes in this biblical setting against nomads and ancient tribes, some of whom had never even seen electricity, but they knew how to use modern weapons. The little known Federation and its tribesmen were fiendish, feral and forbidding, and I was to learn quickly to both love and hate them equally.

In 1961, British action had to be taken to curb ‘toll collecting’ by the Quteibis, which had degenerated into an unacceptable level of looting and pillaging of the caravans passing through the Radfan. But the action caused a resentment and a bitterness which never diminished. Consequently, the Radfan tribes provided excellent material for Yemeni and Egyptian propaganda. Following the Yemen revolution of September 1962, Egypt took every opportunity to support the Yemen claim to South Arabia by stirring up subversion against the Federation and against British rule in Aden. And a virulent programme of propaganda streamed out continually from Radio Cairo, Radio Sana and Radio Taiz. It was both clever and entertaining, and could be heard, not just in the duty free shops of Steamer Point, but from almost every transistor radio in almost every house and back street in Aden. The subversion increased throughout 1963 and, despite frontier air and ground patrols, and air action against dissidents, the infiltration of arms and money steadily increased. Tribesmen were invited into the Yemen for free training courses at the end of which they were provided with gifts of rifles and ammunition, a currency they very well understood.

Despite the fact that all the Radfan tribes sued for peace and were thoroughly chastened by the successful RADFAN operation in 1964, it did not stop the steady infiltration of Egyptian and Yemeni sponsored dissidents. They maintained a constant harassment, especially in the Radfan area, on our soldiers up-country, who were endeavouring to pursue a ‘hearts and minds’ policy by assisting the tribes to build schools, roads, wells and other agricultural facilities. But it was too little, and much too late: a great deal of the good work was undone by hostile infiltrators before it was even completed. The exposure to sniper fire of our Royal Engineers while helping the villagers and building roads, resulted in a number of casualties among them. Indeed, I am the proud owner of a 10Field Sqn, Royal Engineer’s Tie struck specifically for those who had worked on building the Dhala Road through the Radfan area, simply because of all the top cover missions we had flown in their support. Even so, this new colonial war went almost unnoticed in London, and yet it was turning into a miniature ‘Vietnam of the British’.

The beauty of my role as a fighter pilot, though, was that all the problems of life in Aden paled into insignificance once I was airborne and leading a Hunter four ship in battle formation up country. Few Europeans ventured into the wild desert and mountains of the Federation, which covered some 112,000 square miles around the seventy-five square miles of the British Colony of Aden. Inland from Aden beyond the lush oasis of Lahej, the sandy desert ended in a huge, black, craggy rock massif of the Radfan rising above 7,000 feet. It was a natural barrier, closing the way into the Yemen to all but the hardiest of travellers. Yet the ancient Frankincense trail from the south and east ran straight through it. There is a letter in the Squadron diaries written by Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sir Ralph Cochrane, a 1920s Squadron Commander, stating that in return for some help one day the Emir of Dhala had promised him the freedom of safe travel throughout the land. The Emir controlled the whole of the notoriously savage Radfan area, the biggest hotbed of dissension in the Federation. By the early 1960s no European had ever come out of the Radfan alive: at least not with his balls connected in the right place! Sir Ralph would have been the only European to survive a visit at that time. He said, “Luckily, I never had to hold the Emir to his promise!”

Service in Aden produced curious effects on different individuals. To some the heat, sand and discomfort were anathema; they claimed to have hated every moment of it but, curiously enough, proceeded to talk about it with a kind of reluctant nostalgia for the remainder of their lives. Many were the short-term visitors, and unaccompanied married men, to whom I used to listen in the Jungle Bar of Khormaksar Officers’ Mess, moaning into their beers about the miserable place. But for others, especially those of us there for long periods, the desert held a fascination.

The isolation and the vague but irresistible feeling of a link with Biblical times has affected many Britons who have...