- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

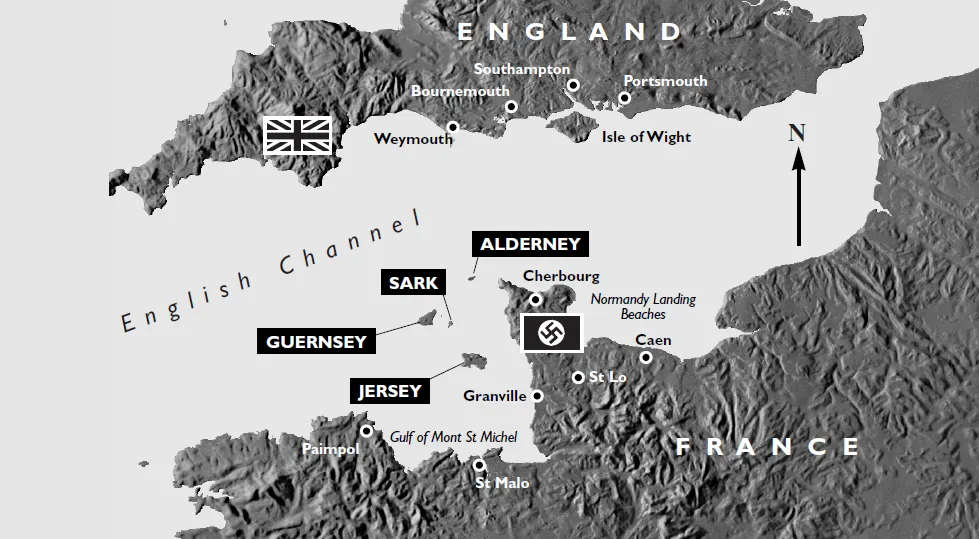

While the Germans did not succeed in invading Britain during World War II, they occupied a number of islands in the English Channel. The English population continued to lead fairly normal lives, while the German occupiers built some of the most extensive fortifications of the Second World War. As the war progressed, British commandos made occasional attacks, resulting in harsher conditions on the islands. The German garrisons were totally isolated by the D-Day landings, but managed to hold on through the following winter to surrender in May 1945. The author, a renowned military historian, examines these questions with complete candor, in addition to his study of the famous fortifications. All of the wartime events and the islands and their fortifications as they are today are covered in the popular Battleground Europe style, with illustrations, maps and then-and-now photographs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Atlantic Wall: Channel Islands by George Forty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

HOW WE MARCHED!

‘After all, what is the road there for but for marching – and how we marched! Day after day in the sun and dust. Forty-five miles was our longest day's march.’ That is the opening paragraph of a report1 written by a German infantry officer, Major Dr Albrecht Lanz, who although he was only a battalion commander in 216 Infantry Division, was destined to become the first military governor of Guernsey, the first British soil to be occupied by the Nazis during World War Two. His battalion had forced marched from Lys in Belgium, via Caen, to the Channel coast around Cherbourg and was now occupying this beautiful area with, as he puts it: ‘its shimmering white bays, where the water, crystal-clear and the snow-white sand invited us to bathe. Every company commander was King in his own Kingdom. As the well-to-do inhabitants everywhere had fled, quartering caused no difficulty. In a very short time men and horses were provided for in the best of style, and the alloted task – securing the coast – surveyed in all directions and carried out with soldierly thoroughness.’

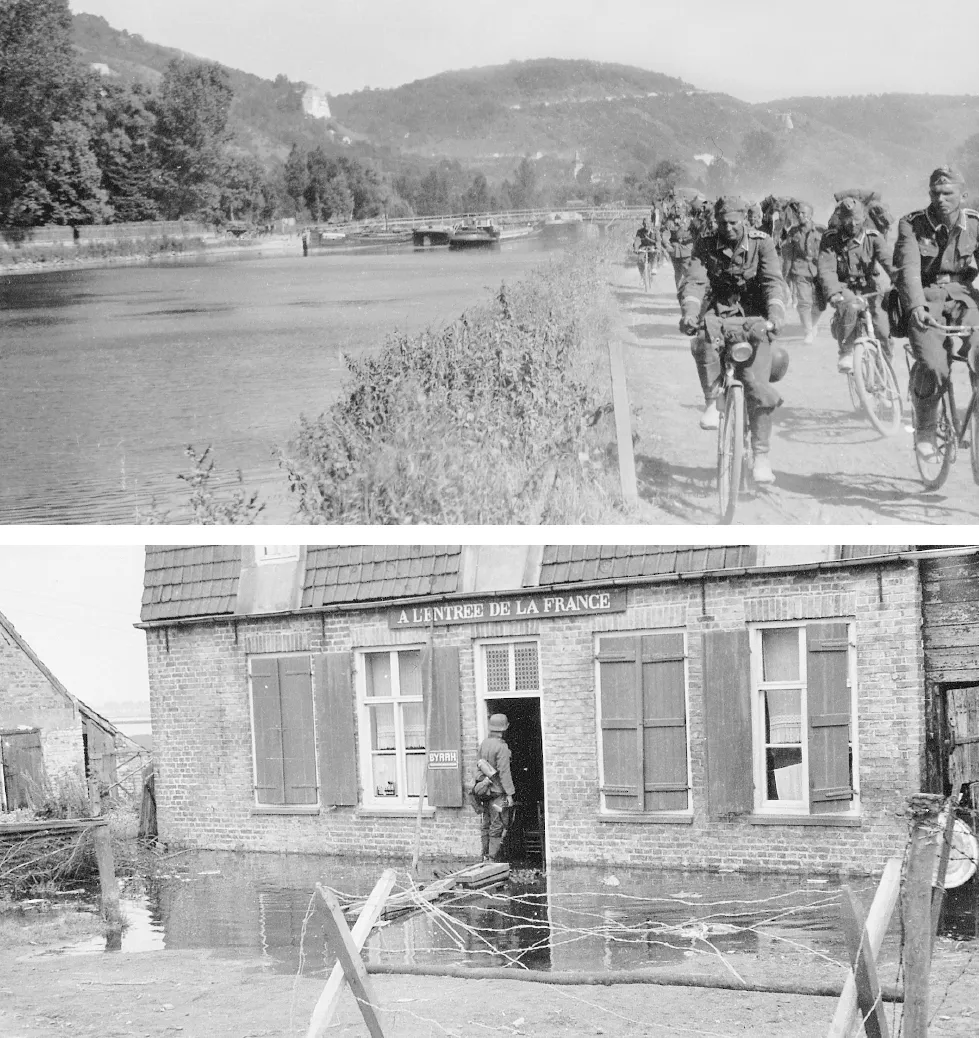

How we marched! This photograph shows men of the 216. ID, who would be the first German soldiers into the Channel Islands, during their all-conquering march through Europe. H. G. Sandmann

After leaving Duisburg on 9 May, they went on through Belgium and France, reaching the Normandy coast at Laurent-sur-Mer on 25 June. As the photos show, despite the tactics of the Blitzkrieg, the majority of the German infantry still marched, whilst their artillery and supply trains were horsedrawn.

The young, fit and well-trained landser (infantryman) marched and fought their way across the Low Countries, crossing into France and finally marching down the Seine valley, on though the bocage with its high hedgerows, until they reached the sea. All photos were taken by Gerhard Sandmann, late father of Hans-Gerhard Sandmann

The leading infantry would soon be followed by more and more German servicemen – soldiers, sailors and airmen, as the Wehrmacht tightened its grip on defeated France. Adolf Hitler met a French delegation at Compiègne on 21st June, to accept their surrender, deliberately chosing the same railway carriage in which the Versailles treaty had been signed on 11th November 1918. It had been a remarkable few short weeks since he had launched his Blitzkrieg (Lightning War) on the West on 10th May, swiftly overrunning Holland, Belgium and France and forcing the battered British Expeditionary Force and remnants of the other Allied armies, back over the beaches and into the Channel, where they would have perished but for the remarkable heroism of the Royal Navy, ably supported by the ‘Little Ships’. The Battle of Britain was yet to be fought and it must have appeared to the victorious Germans that nothing could prevent them from, as they put it: ‘Fahren gegen England!’ (Marching against England!). And although such dreams of conquest were still ‘pie in the sky’ for most German servicemen, they would soon become a reality for a small number, amongst whom Albrecht Lanz's men would play a significant part. However, before dealing with the German invasion, we must look first at the reasons why it was so simple and easy to achieve.

When the German occupation forces did arrive in the Channel Islands it would be the very first time that an invader had landed on any part of these beautiful and tranquil islands since 1461, when Jean de Carbonnel, commanding an expeditionary force sent by the Grand Seneschal of Normandy, had captured Mont Orgueil Castle on Jersey. For the next seven years the island was under French rule, until the English retook it in 1468. Since that date the islands had remained as dependencies under the British Crown, although never strictly part of the United Kingdom. Both the main islands of Jersey and Guernsey had Lieutenant Governors (senior serving British Army officers) and Bailiffs (Chief Justices) who were appointed by the Crown. The Bailiffs were the link between the islands administrative bodies and the Lieutenant Governors. At the start of the Second World War, the population of the islands was under 100,000, with roughly 50,000 on Jersey, 40,000 on Guernsey, 1,500 on Alderney and just 600 on Sark, the majority of whom were born and bred islanders. There were also some expatriate British, some itinerant workers from Ireland and the continent, plus a few Jews although most of the small Jewish community had already moved to England. The mild climate and delightful scenery undoubtedly made the Channel Islands a perfect place to live. Adolf Hitler thought much the same, indeed he went so far as to say that after the war was over and Germany had won, the islands would be handed over to Robert Ley, Head of the German Labour Front, because: ‘… with their wonderful climate, they constitute a marvellous health resort for the Strength through Joy organisation. The islands are full of hotels as it is, so very little construction would be needed to turn them into ideal rest centres.’2

Two of the ‘little ships’, loaded with BEF on their way to England and safety. Author's Collection

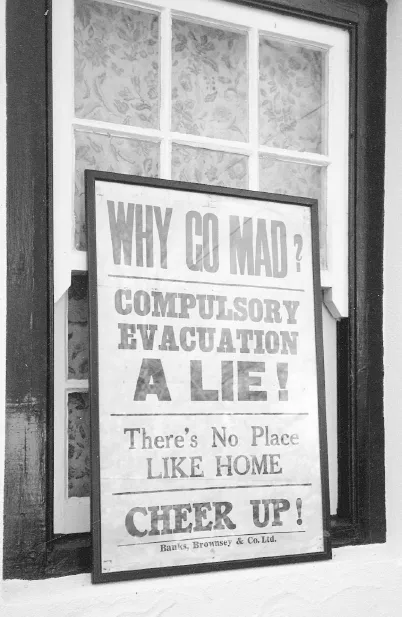

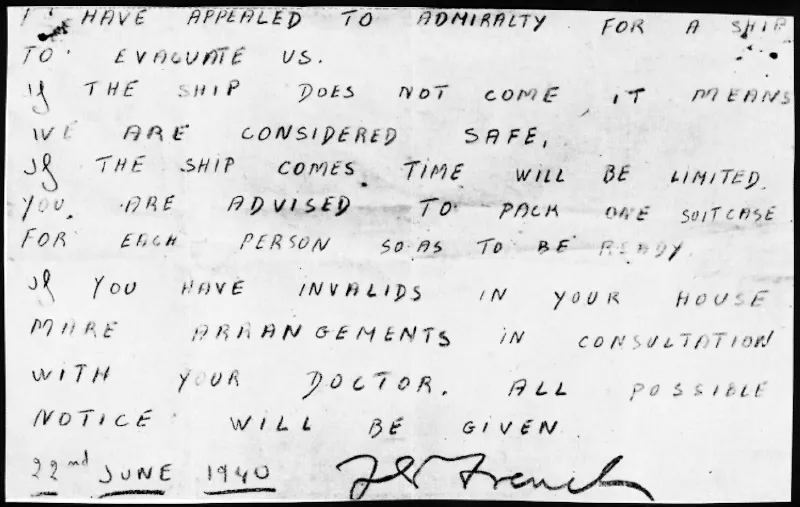

Public notice about evacuation – designed to calm the population. It is now on show in the Occupation Museum, Guernsey. (Brian Matthews)

Muddle and Indecision.

At the start of the war there were no clear cut decisions made as to how the islands would be guarded. Acting on their own initiative, the two Lieutenant Governors had immediately ordered the call-up of their island militias, a decision that was eventually approved by both the War Office and the Home Office. The passing by Parliament in London of the National Service (Armed Forces) Act naturally affected the young men on the islands, who, as they had done at the start of the Great War, had swiftly volunteered in considerable numbers, to serve in the armed forces of Great Britain. The general effect of this in the early months of the war, was a gradual depletion of manpower from the islands, thus seriously weakening the militia. At the same time, the Lieutenant Governors had continually asked for anti-aircraft and coastal defence artillery – plus the skilled manpower to man them – but received little positive help from the ‘mandarins’ of Whitehall. Indeed, at that time the view of the War Office was that the likelihood of an attack on the Channel Islands was remote and therefore, in their opinion, the weapons would be better employed elsewhere. Even at this early stage it was clear that in the general opinion of the British Government, the islands were not worth defending as they had no real strategic value. This apparently cynical approach did, however, have a basis of sound commonsense, as it would clearly have taken a very large garrison to defend the islands against an all-out attack – and there were few enough trained soldiers available to protect the mainland of Great Britain now that the BEF had gone to France and Belgium. Also, and as was abundantly clear from the scale of destruction and chaos which the German invasion had brought upon the civilian population of Poland, such a defensive battle would wreck the infrastructure of the islands and kill many of their inhabitants. Therefore, positive steps were to be taken to demilitarise the Channel Islands and the regular garrison on Guernsey (1st Battalion The Royal Irish Fusiliers) was removed.3, leaving just some training establishments as the only regular troops on the islands.

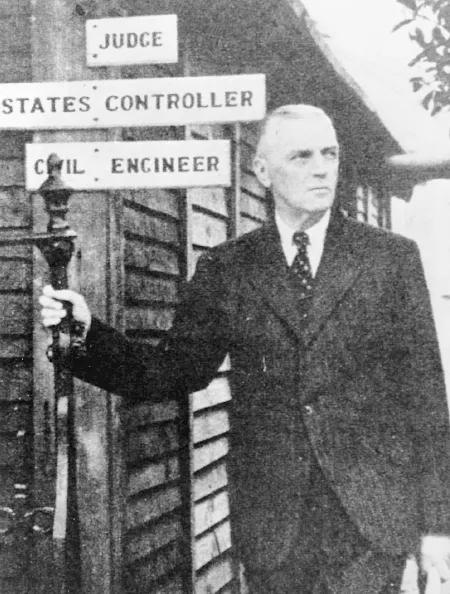

Mr F G French, the Judge (Chief Adminstrator) of Alderney was faced with the problem of what to do with his small island's population, which at that time was just over 1,000. He decided upon evacuation and his decision was supported by the majority – especially after they had seen all the military depart with their families. An orderly evacuation therefore took place on Sunday, 23rd June, when all but a handful were taken off by ship. IWM – HU25940

The note which was posted some eight days before the Germans arrived.

However, as the Germans swept through France and the Low Countries, views changed. Initially it was decided (at a meeting of the War Cabinet on 12 June) that the islands should be defended and approval was given to send two infantry battalions as quickly as possible to replace the training establishments that were stationed there. This was rapidly followed by a complete change of heart as it swiftly came home to all concerned that when the Germans controlled the Channel coast – and this would now be in a matter of days or even hours – the islands would then lose what little strategic importance they had and were thus not worth defending. The training establishments would therefore be withdrawn, the local militia ordered to concentrate on security and anti-sabotage, whilst plans were made to destroy any airfield facilities on the islands which could be of use to the enemy. It was further recommended by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) that the Lieutenant Governors be authorised to surrender the islands should the Germans land, so as to prevent unneccessary bloodshed. Although this was the Army view and plans were put into effect to withdraw the troops concerned, there seems to have been a lack of liaison between the three Services. For example, the Admiralty initially said that they were no longer interested in the Islands and agreed with the War Office that the airfield facilities could be destroyed, whereas the Air Ministry desperately wanted them to remain up and running, so as to be available for use in operations to support of the BEF in France. This need was clearly evidenced by the fact that both 17 and 501 Fighter Squadrons of the RAF, moved their Hurricanes to Jersey from Le Mans and Dinard on 18 June. In addition to the needs of operational aircraft, both Jersey and Guernsey Airways (based...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Other guides in the Battleground Europe Series:

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE: HOW WE MARCHED!

- CHAPTER TWO: DENN WIR FAHREN GEGEN ENGLAND!

- CHAPTER THREE: SETTLING IN – THE FIRST SIX MONTHS

- CHAPTER FOUR: 1941 – THE YEAR OF CHANGE

- CHAPTER FIVE: 1942 – MORE MEN AND MORE BUILDING

- CHAPTER SIX: 1943 – CONTINUED GROWTH

- CHAPTER SEVEN: 1944 – D DAY AND THE HUNGER WINTER

- CHAPTER EIGHT: 1945 – SURRENDER AND LIBERATION

- CHAPTER NINE: BRITISH COMMANDO RAIDS

- CHAPTER TEN: EXPLORING THE ISLANDS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX