- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

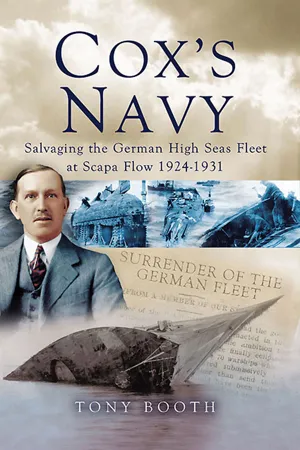

A deep dive into the biggest salvage operation in history: the recovery of German warships—the Allies' spoils of World War I—from Scottish waters.

On Midsummer's Day 1919 the interned German Grand Fleet was scuttled by their crews at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands despite a Royal Navy guard force. Greatly embarrassed, the Admiralty nevertheless confidently stated that none of the ships would ever be recovered. Had it not been for the drive and ingenuity of one man there is indeed every possibility that they would still be resting on the sea bottom today.

Cox's Navy tells the incredible true story of Ernest Cox, a Wolverhampton-born scrap merchant, who despite having no previous experience, led the biggest salvage operation in history to recover the ships. The 28,000-ton Hindenberg was the largest ship ever salvaged. Not knowing the boundaries enabled Cox to apply solid common sense and brilliant improvisation, changing forever marine salvage practice during peace and war.

On Midsummer's Day 1919 the interned German Grand Fleet was scuttled by their crews at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands despite a Royal Navy guard force. Greatly embarrassed, the Admiralty nevertheless confidently stated that none of the ships would ever be recovered. Had it not been for the drive and ingenuity of one man there is indeed every possibility that they would still be resting on the sea bottom today.

Cox's Navy tells the incredible true story of Ernest Cox, a Wolverhampton-born scrap merchant, who despite having no previous experience, led the biggest salvage operation in history to recover the ships. The 28,000-ton Hindenberg was the largest ship ever salvaged. Not knowing the boundaries enabled Cox to apply solid common sense and brilliant improvisation, changing forever marine salvage practice during peace and war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cox's Navy by Tony Booth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Muck and Brass

On the front of the Blakenhall Community Centre in Wolverhampton’s Dudley Road, there is a blue plaque, which reads:

Ernest F. G. Cox

Engineer

And

Marine Salvage Expert

Educated Here

1890–1897

Engineer

And

Marine Salvage Expert

Educated Here

1890–1897

During the 1890s the community centre was known as the Dudley Road Free School, and the only formal education young Ernest received was the seven years he spent in its classrooms. Ernest Frank Guelph Cox was born on 12 March 1883, a spit away from the Free School, at 55 Pool Street, in a cramped Victorian terrace. The area was in the heart of Wolverhampton’s industrial metalworking district, which Ernest saw every day as he walked to school. He would set off from his house at the end of Pool Street, past the Drayton tin plate works, then into Drayton Street itself, and finally past the Vulcan ironworks on his five-minute walk to the school gates.

Altogether his parents, Thomas and Eliza, raised eleven children – Ernest being their last. Thomas was a tailor by trade and he tried hard to provide for his large family, but could not manage without the help of his elder children. In true Victorian Black Country spirit Ernest was brought up thinking that earning was better than learning, and at the age of fourteen, he gave up the chance of higher education to help support his family. Thomas managed to find Ernest a job as an errand boy for a draper friend, but he hated the toil. Whatever the weather, he was seen trudging around the streets of Wolverhampton between the different drapers’ shops clutching packages, letters or samples of stock, or sweeping floors and dusting shelves. The monotony was smothering him slowly and, regardless of his parents’ wishes, Ernest’s ability to stick with the mind-numbing drudgery began to wilt.

Even when he was young, Ernest was drawn towards engineering. Its pragmatic approach to solving mechanical problems excited his imagination. Like all large cities at the close of the nineteenth century, Wolverhampton was lit by gas. In the early 1880s, Midlands’ engineer Thomas Parker had been devising ways to exploit electricity, which he believed to have great potential both to power and to light commercial and domestic premises. His machinery would later appear throughout England’s early power stations. Wolverhampton had its own power station by early 1895, which was based in Commercial Road. Its supply could only cover an area of about 5½ square miles. The noisy dynamos with their spinning wheels and clacking motors fascinated Ernest. Stealing into the main generating house he stared at all the oily, noisy machinery needed to make the coal-fired generators produce their power.

The sight of men in dirty, sweat-grimed clothing, rushing around and wiping away oil leaks and checking gauges, made him want to be among them and not at the beck and call of a town draper. Although Wolverhampton residents tended to ridicule the new power source, Ernest, like Thomas Parker, intuitively felt that electricity would one day replace gas as the country’s main lighting and perhaps even become its main power system. For another year he struggled on as an errand boy and spent every free moment reading all available material relating to electricity and its uses. When he felt confident that he knew his subject, Ernest approached the power station’s Chief Engineer for work. The clean-looking boy stood before the Chief Engineer, with a face that had never even broken into a sweat, let alone seen the dirt of a hard day’s work. Although Ernest came from a very modest background, even by late Victorian standards, Thomas and Eliza had instilled in him a sense of good speech and behaviour – a talent Ernest could and did turn on and off as needed throughout his life.

He looked up at the generators he had seen so many times before from the power station’s doors and casually opened a conversation about the benefits of operating the station’s triple dynamo system as opposed to others of the time. He commented on the subtleties of how they pushed out their 350 kilowatts to the small substations and how they, in turn, converted the power into smaller 200-volt units for domestic consumption. Cox soon had the Chief’s full attention. Within twenty minutes Ernest convinced the Chief Engineer that he fully understood how electricity was generated, what could go wrong, and how to fix it. Ernest got the job. He also got a pay rise of a shilling a week more than his draper’s employment. At last Ernest’s mind would be stimulated. He was only seventeen years old.

The theory Cox had spent a year absorbing was now being put into full effect through practical application. He immersed himself in all aspects of the power station’s operation and soaked up every facet of his new job with ease. Whatever difficulty arose, he doggedly worked at it until the problem was solved. But in less than a year, too much repetition had already crept into his daily work routine and the challenges became fewer. Cox had soon learnt all he could from the Wolverhampton power supply and began looking for a bigger challenge. Eventually a vacancy arose in Leamington for an assistant chief engineer. Cox wanted the post badly, but he was too young and lacked the necessary experience. He knew he could either let the chance go and stay where he no longer felt challenged – or he could lie. Against the advice of his friends and colleagues Cox decided to lie. He applied, saying he was much older and had several years’ experience in electricity generating rather than just the one. He was summoned to Leamington for an interview and assessment of his skills. Once he arrived it was obvious to the interview board that Cox was far too young for the managerial post. However, Cox again applied his charm and wide knowledge of power-station engineering to defend his position. Despite his youth, and his attempt to deceive them, the interview board was sufficiently impressed by his knowledge and self-confidence.

Cox was soon living in Leamington, facing the new challenges of an assistant chief engineer. Two years later, he felt confident enough to apply for a chief engineer’s post. A domestic power supply was to be built in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight. The post included designing and building the power station from the foundations upwards, as well as calculating usage and laying down every power line, generator and substation needed to make the project a commercial success. As the popularity of electricity spread, its application as a revolutionary energy source also grew. A supply was being planned in Hamilton, near Glasgow and was designed for industrial output. Cox leapt at the chance for another challenge, applied for the job and, predictably, got it. Such a post would have satisfied many in the electrical generating field for the rest of their working lives, but when the plant was running at full capacity, Cox was ready to move again, this time to the nearby town of Wishaw where another plant was to be built. He was by now only twenty-four years old and already renowned throughout the industry as a leading figure in changing the nation’s gas supplies to electricity. But he knew he could go no further in seniority and began looking for a fresh stimulus.

Tension between Britain and Germany had been accelerating for some years as both countries were locked in a frenzied naval arms race. Cox saw steel as the next emerging market. Wishaw Councillor Robert Miller got to know Cox well as a widely respected and competent businessman. Miller owned a large steel works known as the Overton Forge, near Wishaw, and wanted Cox to run the business and develop its potential. Miller first asked Cox to put together a recovery plan and then invited him to dinner at his house for an informal meeting. While discussing the various problems and how to solve them, Cox met Miller’s twenty-three-year-old daughter, Jenny Jack. Like many Midlands men of his day, Cox’s Victorian upbringing had taught him that women must be respected at all costs, but belonged in their place, which was to be protected from the harsh realities of life. They became friends, a relationship that could go no other way but for the twenty-somethings to fall in love. Within the same year, 1907, Cox took over the Overton Forge and married his new boss’s daughter. The following year the Coxes added their own baby girl to the family. She was named Euphemia Caldwell, but the dark-haired little girl was always affectionately known as Bunty or Bunts.

Cox was now nearly twenty-seven years old and wanted to open his own forge in the hope of supplying the growing military build-up, but like many young entrepreneurs he lacked investment capital. Jenny suggested that he approach her cousin, Tommy Danks, as a potential investor. Danks was a young man who had inherited a fortune and was systematically spending it all between London, Paris and the French Riviera. He readily agreed to back Cox as long as he did not have to work in the forge. Publicly, Cox always showed his appreciation for Danks having taken the chance to invest in his new business, but in reality he disliked the playboy. Cox’s humble working class background had taught him to appreciate a hard day’s work, and the pay a man gets for it. Danks’s frivolous lifestyle, supported by inheritance, grated against his work ethic. But he needed an investor and was more than happy to have complete control over his new business venture. And so the firm Cox & Danks of Oldbury, near Wolverhampton, began trading in 1913.

Strong rumours were suggesting that war with Germany now looked imminent, and Whitehall was awarding munitions contracts. Cox won a contract to produce brass shell cases. The work was repetitive and gave no engineering challenges once the machinery was in place and his men trained. But the war, which both sides thought would end by Christmas 1914, meant that Cox & Danks went on stamping out shells, profitably feeding the Allied war machine for nearly four more years. Once the 1918 armistice was signed and the lucrative contracts began to dry up, metal foundries throughout Britain were laying off men or closing down. But Cox & Danks were in a very strong financial position when they finally lost their Government work. Cox had enough capital to buy out his playboy partner. Tommy Danks agreed. Now Cox was the sole owner of a foundry, albeit without any large contracts to employ his workers or keep him in business for much longer. The fields of France and Belgium, however, were strewn with twisted metal and war machinery, which now had to be cleared. To Cox, the war debris was gold, and he set up a new foundry in Sheffield to cope with the tons of metal collected and shipped back to England for reprocessing.

The Royal Navy was reducing operations to peacetime requirements and Cox made his first venture into shipbreaking when the two ageing battleships, HMS Orion and HMS Erin, were decommissioned and put out to tender for breaking. He bid for the two old warships and they became the property of Cox & Danks. Because his two foundries were inland, Cox had to open a yard at Queensborough on the Isle of Sheppey to handle the initial breaking before parts were delivered to Oldbury and Sheffield. After the purchase and full cost of breaking up were taken into account, Cox still doubled his money. But the glory days for the war scrap merchants were numbered. The Western Front was virtually cleared of the most lucrative metal and the military scale-down was also coming to an end, making the future of Cox & Danks look very bleak indeed. Cox needed scrap metal in large quantities – fast. Everywhere he looked the land had been picked clean. But five years before, on Midsummer’s Day 1919, another man’s actions were destined to play a major part in Cox’s next, and certainly most ambitious, decision of his life.

Chapter 2

Coup de Grâce

Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter was from a solid Prussian aristocratic family and firmly believed that the honour of the Imperial High Seas Fleet and Germany went before everything. He had the outstanding naval career expected of an officer who reached admiral rank, but unlike most senior officers, von Reuter achieved success while remaining both respected and popular among his officers and men. When hostilities ceased along the Western Front, the Allies insisted that Germany hand over its entire fleet until the final peace negotiations could be settled. On 18 November 1918, with their guns disabled, all seventy-four warships left Wilhelmshaven in north-west Germany and were later met by the light cruiser HMS Cardiff to lead them to the waiting Allied armada.

Admiral Hugh Rodman of the United States Navy later recalled that the sight of the Cardiff reminded him of an old farm in his home state of Kentucky, ‘where many times I saw a little child leading by the nose a herd of fearsome bullocks’. As the Allies surrounded the German fleet, with all guns loaded and pointing directly at them, many among the British crews hounded the Germans by banging every tin cup, ratchet, crowbar and any other metal object to show contempt for their enemy. Seaman Sydney Hunt remembered the sea-born nervous tension.

We were allowed up one at a time from our action stations, and we could not believe our eyes. It was like a wild dream, just miles of ships. That day of course all leave was stopped. Officers and Petty Officers all got tight, and the crews got hold of anything they could and just bashed it to hell.

In return many German crews replied by mustering their bands and repeatedly playing military marching songs to goad their captors as the solemn procession crossed the North Sea in a black, acrid fog created by the smoke billowing from more than three hundred funnels.

Upon arrival at Scapa Flow, von Reuter was nothing more than a chief caretaker responsible for the administration and organization of maintenance, supplies, medical treatment and all other forms of shipboard routine needed to keep the fleet in serviceable condition. Steaming into the Flow aboard the battleship Von der Tann, he later wrote:

The lower parts of the land showed signs of rude cultivation, trees and shrubs were nowhere to be seen. Most of it was covered in heather, villages were just in sight on the land in the far distance – apart from which here and there on the coast stood unfriendly-looking farmhouses built of grey local stone. Several military works, such as barracks, aeroplane sheds or balloon hangars, relieved the monotonous sameness; in ugliness they would beat even ours at a bet.

Von Reuter thought he would be relieved after delivering the fleet to Scapa Flow and then be allowed to return home. About six months later he was still there, reduced to commanding mutinous skeleton crews aboard rat-infested and by now unserviceable ships, on which rumours and boredom were the new enemies.

Admiral Sir Sydney Fremantle was responsible for guarding the High Seas Fleet with a squadron of six battleships, their accompanying destroyers and a patrol of armed drifters. These were fishing boats specifically designed to allow their nets to drift with the current, unlike trawlers, which pull their nets at deep levels beneath the sea. Fremantle’s first directive was to order the lowering of all German ensigns, which could not be hoisted again without Admiralty permission. The German crews saw this as a gross insult. They were not prisoners under the terms of the armistice, only internees who still commanded their own vessels. As commander of the German fleet, von Reuter was allowed access to British newspapers that had to be delivered four days late lest he act on any fresh news. His officers and men then had to rely on information filtering down through the ranks, which, all too often, was laced with speculation and rumour as it travelled around the fleet. As time moved on, ‘steel-plate sickness’, a marine equivalent of the barbed wire fever known to have affected thousands of POWs during the First and Second World Wars, began to affect the officers and men. Their uncertain future also played a large part in low morale, as the Allies kept prevaricating over how the fleet should be divided.

Able Seaman Braunsberger aboard the battleship Kaiser kept a diary throughout his internment. As the situation worsened he recorded the general atmosphere within the High Seas Fleet.

The further spring advanced, the more monotonous it became for us. We received little post, no newspapers and we could not receive news over the radio either. The reluctance to work got worse. Engine maintenance was no longer properly carried out, the water for the boilers turned salty. The power was often cut so we had to sit in the dark in the evening. Lunch was often cooked on the coal burner and the diet got worse. Always the same comrades round you, always the same view of land. On top of that the agitation of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council which sowed only hate and strife. Even though we still believed in a happy ending, all this turned us into psychopaths.

Later that same spring, news reached the German fleet that the Allies had finally decided their fate. A public statement indicated that Germany was to get a few token warships and the might of their fleet was to be divided up among the Allies and the United States. The news was a crushing blow and tempers flared as everyone argued over how Berlin would react to the ultimatum. Von Reuter knew his Government had three options: they could reject the terms; try to negotiate a better deal or, which was inconceivable, agree. If Berlin rejected the terms then hostilities would commence with immediate effect and von Reuter would scuttle the fleet before the Allies could storm his ships. His thinking was based on a standing order from the German leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, that all ships must be scuttled if surrender or a takeover was likely.

A negotiation could reap better rewards for the German people because the fleet could possibly be sold rather than taken as a war prize. Von Reuter saw an outright agreement as impossible. On 29 May 1919, Reichstag Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann publicly announced that the German Government had rejected the Allied peace terms. The Allies replied by issuing a warning to Berlin demanding an acceptance of the terms – or at noon on 21 June the horror of the First World War would begin again.

As usual, the news hit Scapa Flow four days later and the shock wave travelled through the fleet like an enemy broadside. Von Reuter decided he had no option other than to obey his Kaiser and scuttle the fleet. After all, he reasoned, under any armistice a state of war still existed and the ships remained German property. But how could he orchestrate the synchronized scuttling of seventy-four warships with limited communications – and in front of Fremantle’s battle squadron? Von Reuter spent more than two weeks hatching the plan, which ultimately hinged on the goodwill of the Royal Navy. By now the German fleet had been in Scapa Flow for seven months and although German and British personnel were strictly forbidden to fraternize, illicit trading had sprung up between the two sides. Destroyer Captain Friedrich Ruge recalled:

Officially we were not allowed to have any contact with the British but of course in seven months that could not quite be carried out. We ourselves had quite a lot of contact with drifters. They were not only on guard, they carried mail around and our provisions.

Von Reuter’s key was in the distribution of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Muck and Brass

- Chapter 2: Coup de Grâce

- Chapter 3: Arrogance or Genius

- Chapter 4: Quacks and Facts

- Chapter 5: Ships on Ships

- Chapter 6: Oil and Ash

- Chapter 7: Bigger Ships, Bigger Problems

- Chapter 8: Coming Alive

- Chapter 9: Balancing Billiard Balls

- Chapter 10: Seydlitz

- Chapter 11: Kaiser and Bremse

- Chapter 12: Heavy Metal

- Chapter 13: Von der Tann

- Chapter 14: The Prinz

- Chapter 15: Selling Out?

- Chapter 16: HMS Thetis

- Chapter 17: Salvage Heritage

- Chapter 18: Family Man

- Sources and Bibliography

- Index