- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author relies to a great extent on contemporary accounts of a large number of British men—and women—who were unwittingly caught up in this appalling war. As well as surviving the efforts of their determined enemy, the Russians, they had to overcome the harshest weather, rampant disease and woefully inadequate administrative support. As revealed to a shocked nation by the first war reporters, medical care was largely non-existent and wounded faced the trauma of being left for days without medical attention. This was where Florence Nightingale came in. Battles were prolonged, desperate and hugely costly. The Crimean War was the catalyst for the modernisation of the Army, due to the disgraceful injustice of conditions and lack of leadership and care by many in authority.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conflict in the Crimea by D. S. Richards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

| Dramatis Personae | |

| Preface | |

| 1 | The Drift to War |

| 2 | Battle of the Alma |

| 3 | A Day of Disaster |

| 4 | Inkerman: A Soldier’s Battle |

| 5 | The Approach of Winter |

| 6 | Kertch, the Mamelon, and the Quarries |

| 7 | Lions Commanded by Asses |

| 8 | The Fall of Sevastopol |

| 9 | The Assault on Kinburn |

| 10 | An Uneasy Peace |

| Bibliography | |

| Index |

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

| Sister Mary Aloysius | Volunteer Nurse |

| Lady Alicia Blackwood | Volunteer Nurse |

| Lieutenant W.A. Braybrooke | 95 Regiment of Foot |

| Lieutenant Hon. Somerset J.G. Calthorpe | Headquarters Staff |

| Lieutenant George Carmichael | 95 Regiment of Foot |

| Lieutenant Hon. Henry Hugh Clifford | 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade |

| Cornet George Clowes | 8 Hussars |

| Lieutenant F. Curtis | 46 Regiment of Foot |

| Lieutenant George Frederick Dallas | 46 Regiment of Foot |

| Mrs Henry Duberly | Wife of an officer in the 8 Hussars |

| Captain Nicholas Dunscombe | 46 Regiment of Foot |

| Captain Arthur Maxwell Earle | 57 Regiment of Foot |

| Trumpeter Robert Stuart Farquharson | 4 Queen’s Own Light Dragoons |

| Mr Roger Fenton | War Photographer |

| Sergeant Major Henry Franks | 5 Dragoon Guards |

| Lieutenant Richard Temple Godman | 5 Dragoon Guards |

| Sergeant Major Timothy Gowing | 7 Royal Fusiliers |

| Captain Bruce Hamley | Royal Artillery |

| Captain Robert Hodasevich | 2 Chasseur Brigade |

| Captain John Hume | 55 Regiment of Foot |

| Lieutenant Colonel Atwell Lake | ADC to General Williams |

| Sergeant Albert Mitchell | 13 Hussars |

| Mr A. Money | Non Combatant |

| Lieutenant Frederick Morgan | 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade |

| Major Reynell Pack | 7 Royal Fusiliers |

| Lieutenant George Shuldham Peard | 20 Regiment of Foot |

| Trooper William H. Pennington | 11 Hussars |

| Captain Robert Portal | 4 Queen’s Own Light Dragoons |

| Major Whitworth Porter | Royal Engineers |

| Lieutenant George Ranken | Royal Engineers |

| Douglas Arthur Reid MD | Assistant Surgeon 90 Regiment of Foot |

| Captain Edmund Reilly | Royal Artillery |

| Mr William Howard Russell | The Times War Correspondent |

| Humphrey Sandwith MD | Physician |

| Lieutenant Edward Seager | 8 Hussars |

| Major Anthony Sterling | ADC to General Sir Colin Campbell |

| Lieutenant Hon. Jocelyn Strange | Scots Fusilier Guards |

| Mr George Cavendish Taylor | Non Combatant |

| Count Leo Tolstoy | Russian Artillery Detachment |

| Ensign Frederick Harris Vieth | 63 Regiment of Foot |

| Lieutenant Garnet Wolseley | 90 Regiment of Foot |

| Captain George Wombwell | 17 Lancers |

PREFACE

Waterloo had been the last act in the Napoleonic War and for the next forty years peace reigned in Europe, but on 28 March 1854 Britain found herself once again involved in conflict with a powerful European nation.

A petty dispute over the custody of the various churches and shrines in Jerusalem and Bethlehem grew into a major political crisis when on 3 May 1853, Prince Menschikoff presented an ultimatum on behalf of the Tsar, to the Sultan of Turkey demanding the acceptance of a Russian protectorate over all Greek subjects in the Ottoman Empire. Britain and France felt bound to lend their support to the Ottomans in order to preserve the balance of power, with Britain in particular, concerned that communication with India might be under threat should the Russians gain entry to the eastern Mediterranean for their Black Sea Fleet. From that point war was inevitable and for the first time in as many years as most people could remember, Britons and Frenchmen found themselves standing side by side as allies against a common enemy. A move which was greeted with enthusiasm on both sides of the Channel.

The first eight months of the war, in spite of two major victories, proved to be something of a testing period to the military and political bodies of Victorian Britain. Encouraged by cheap and efficient postal services, uncensored letters from serving soldiers in the field soon made the general public aware that with the collapse of the commissariat and the inefficiency of the General Staff, the troops were suffering appalling hardships exposed as they were to a Russian winter in barely adequate clothing and only the shelter of a canvas tent. The introduction of the new electric telegraph had made it easy for newspaper correspondents such as William Howard Russell to furnish reports, highly critical of the authorities, to their readers in a matter of hours. The outrage and growing concern of the public was eventually to bring about the collapse of the Aberdeen government and lead to a much improved hospital system and better conditions for the rank and file.

As in previous works it has been my practice to make extensive use of the comments and experiences of the men and women engaged in the conflict in the belief that the contents of their letters and diaries not only add to the interest of the narrative, but serve to illustrate the horror of nineteenth century warfare in a far more effective way. The fact that victory was ultimately achieved, albeit in large measure by the French, was due to the bravery and perseverance of the junior officers and men, rather than the skills of the generals. This is readily apparent from the observations made in those very same letters.

In acknowledging the assistance I have received from many sources, I would particularly like to thank Major CD. Robins OBE, FRHistS for permission to include a number of observations made by Captain Dunscombe, in the book Captain Dunscombe’s Diary published by Withycut House in 2003, and Mr Henry Alban Davies for his permission to include a number of comments made by Captain Dallas in the book Eyewitness in the Crimea published by Greenhill Books in 2001 – both excellent publications which graphically record the discomfort and danger faced by the combatants in the campaigns of that war.

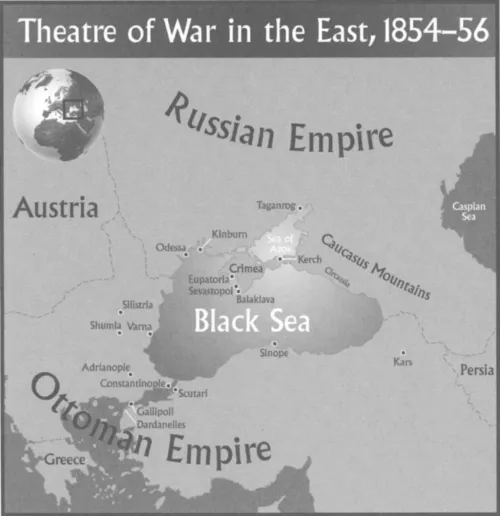

I should also like to express my thanks for the help afforded me by the staff of the National Army Museum at Chelsea, without whose excellent records and research facilities, this work would never have been completed. My thanks also for their permission to include the illustrations and maps so essential to a military history. I would also like to express my appreciation to Susan Econicoff for her assistance in preparing this work for publication.

Chapter One

THE DRIFT TO WAR

Following the overthrow of Napoleon Bonaparte, the people of Europe and Asia had enjoyed several decades of peaceful coexistence, but that tranquil period was about to come to an end when, in November 1853, Russia sought to expand its empire by applying pressure on Turkey, a nation thought by Tsar Nicholas too feeble to resist his demands for a protectorate over all Greek Orthodox subjects in what had become a rapidly shrinking Ottoman Empire which included the Balkans, most of Hungary and, at one time, part of the Ukraine.

Twenty-five years earlier, Russia had gained territory in the Caucasus and the mouth of the Danube from the Turks after supporting the Orthodox Greeks in their battle for independence from Turkish control, and Tsar Nicholas was confident that further pressure on Turkey would result in Russia gaining control of the Dardanelle Straits and with it, maritime access to the Mediterranean for its Black Sea fleet.

Like many similar disputes, that between Russia and Turkey had its beginnings in a long standing religious controversy. In 1453 when Constantinople or Byzantium as it was then known, fell to the Turks, the Moslem religion was in the ascendancy and the position of the Christians in territories controlled by the Turks, became difficult if not hazardous. In later years as Ottoman power declined, increasing numbers of Christians began to visit the Holy Places in Palestine including the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the care of which was shared between the Roman Catholic Church and the Greek Orthodox Church.

In 1740, a treaty signed between the French government and the Sultan of Turkey gave the Catholic Church ‘sovereign authority’ over the Holy Land and in recognition, a silver star, embellished with the royal arms of France, was erected over the alleged site of Christ’s birthplace in Bethlehem by the Franciscan friars who considered themselves the rightful custodians of the shrine. It mattered not that Catholics living in the area were very much in the minority, greatly outnumbered by worshipers of the Coptic and Orthodox churches.

In 1852 Napoleon III created outrage among the rival Christian churches when he won a concession from the Sultan which allowed him to deliver the keys of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem into the custody of the French clergy. Matters came to a head the following year with the arrival in Constantinople of the Tsar’s envoy, Prince Alexander Menschikoff, to demand of the Sultan that all concessions to the Catholic Church be withdrawn, and that a Russian protectorate be recognized over all the Orthodox subjects in the Ottoman Empire. In return, the envoy was authorized to make the offer of a defensive treaty should the Sultan feel threatened by the French for meeting Russia’s demands. The Sultan Abdul Mejid however, believing he had the support of the British and French governments, refused to acknowledge what amounted to an ultimatum from St Petersburg, and on 18 May the Russian embassy was evacuated and Menschikoff set sail for Odessa three days later.

On 2 July Tsar Nicholas ordered his Southern army Corps to cross the River Proth in the Danube plain and occupy the two former Turkish territories of Wallachia and Moldavia; a move which greatly alarmed a British government already nervous of the growing power of the Black Sea Fleet and the threat which Russian access to the Mediterranean would pose to the sea route to India. The Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon reacted immediately by authorizing the dispatch of a squadron of six warships to Besika Bay at the mouth of the Dardanelles. Alarm bells were also sounded in France and Austria who, like Britain, were opposed to any expansion of Russia’s influence in the Balkans.

On 9 October the Porte – the Imperial Court in Constantinople – emboldened by the knowledge that ships of the Royal Navy were already in Turkish waters, notified St Petersburg that unless Russian forces vacated Wallachia and Moldavia within fourteen days, a state of war would exist between Turkey and Russia. No such assurance was given and twenty days later the Sultan’s troops crossed the Danube into Wallachia to begin a series of skirmishes which ended with the Russian forces withdrawing in the direction of Bucharest.

Britain was reluctant to intervene but Napoleon III saw it as an opportunity to regain the international influence his country had lost after Waterloo. A Russian suspicion that the West was actively seeking a confrontation was well founded, for on 27 November Britain and France concluded a defensive alliance with Turkey. Three days later, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet effectively demonstrated its strength by achieving a stunning victory at Sinope, a harbour on the Turkish Black Sea coast less than 200 miles from the main Russian naval base of Sevastopol. In an engagement lasting less than two hours, a flotilla of seven frigates, three corvettes, two screw driven steamers and a number of transports were totally destroyed by the Russians resulting in the deaths of almost 4,000 Turkish sailors. The action, whilst of short duration, had ended in disaster for the Turks for the fires from the burning transports had quickly spread to the harbour buildings and the damage to the port was devastating. One British registered ship was sunk together with the entire Turkish fleet. The only vessel left untouched was a Turkish man-of-war in the process of completion on the stocks. A year later, Doctor Humphrey Sandwith on his way from Constantinople to Kars, called at Sinope, and was not impressed. In his opinion it was ‘a miserable little sea port where the wrecks of burned and sunken vessels were still visible’.

The Tsar ordered a public celebration but news of this Turkish naval disaster led to outrage in Paris and London, motivated perhaps by feelings of humiliation that their ships in the Dardanelles had been too late to prevent it. At a Cabinet meeting on 22 December, Lord Aberdeen the Prime Minister, was persuaded that war with Russia was now inevitable and Queen Victoria who, days before, had doubted whether Turkish independence was worth going to war for, now agreed with the view put forward by Lord Palmerston the Home Secretary, that Sinope ‘was a stain on British honour and that something had to be done’. Little attention was given to the fact that Russia was at war and had every reason to regard the Turkish ships as legitimate targets, since the transports were about to sail for the Caucasian Front with troops and war material.

Diplomatic relations between Russia and Britain and France, and to a lesser degree, Austria and Prussia, had been strained almost to breaking point, but hope of a solution to the crisis was not abandoned despite the threat to Russia of an allied naval force in the eastern Mediterranean. The decision of the Admiralty to detach a squadron commanded by Admiral Dundas to prevent Russian warships from entering the Black Sea was undoubtedly a provocation but the Admiralty considered it unlikely that the Russians would risk a naval engagement and both the British and French admirals were instructed to open fire only as a last resort. T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents