- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

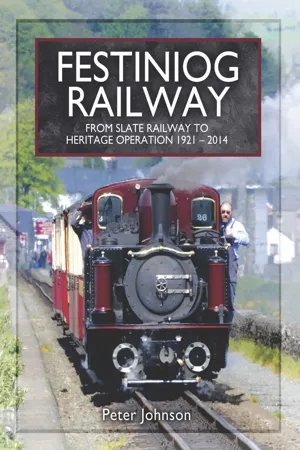

Festiniog Railway: From Slate Railway to Heritage Operation, 1921–2014

About this book

Opened in 1836 as a horse tramway using gravity to carry slate from Blaenau Ffestiniog to Porthmadog, by the 1920s the Festiniog Railway had left its years of technical innovation and high profits long behind. After the First World War, the railways path led inexorably to closure, to passengers in 1939 and goods in 1946.After years of abandonment, visionary enthusiasts found a way to take control of the railway and starting its restoration in 1955. Not only did they have to fight the undergrowth, they also had to fight a state-owned utility which had appropriated a part of the route. All problems were eventually overcome and a 2 mile deviation saw services restored to Blaenau Ffestiniog in 1982.Along the way, the railway found its old entrepreneurial magic, building new steam locomotives and carriages, and rebuilding the Welsh highland Railway, to become a leading 21st century tourist attraction.Historian Peter Johnson, well known for his books on Welsh railways, has delved into the archives and previously untapped sources to produce this new history, a must-read for enthusiasts and visitors alike.The Festiniog Railways pre–1921 history is covered in Peter Johnsons book, Festiniog Railway the Spooner era and after 1830–1920, also published by Pen & Sword Transport.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Festiniog Railway: From Slate Railway to Heritage Operation, 1921–2014 by Peter Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

1921-1924: THE ARRIVAL OF THE WELSH HIGHLAND RAILWAY

When the motion to remove the Ffestiniog Railway Company from the Railway Bill, which brought about the grouping of railway companies, was put to the House of Lords on 17 August 1921, the reasons given were that the Ffestiniog Railway and two other narrow gauge railways would benefit by being under unified control, that negotiations had been under way for some time and that arrangements had been made to secure this objective. If the FR were to be included in the Western group, as proposed, the unification would be impossible; the three lines should all go in together or go out together. The proposal was accepted on the basis that it was in accordance with the grouping principle of the Bill.

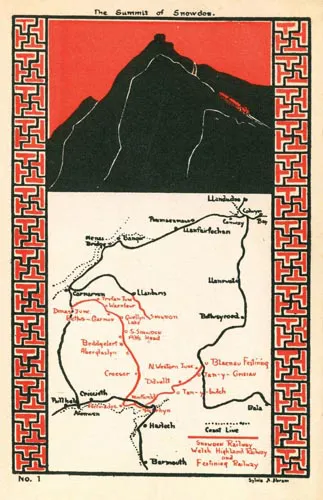

Apart from the FR, the other railways in this narrow-gauge grouping were the Welsh Highland Railway and the Snowdon Mountain Tramroad. When news of the FR’s removal from the Western group reached the Commons, J.H. Thomas, MP for Derby, was most vociferous in his objection, alleging that it was an attempt by the North Wales Power & Traction Company to monopolise North Wales. Replying, the minister said that the FR had been the only light railway included in the Bill so it was right to exclude it.

If he meant the only independent narrow-gauge railway then he was right; for the narrow-gauge Leek & Manifold and Welshpool & Llanfair Light Railways, whilst independent, were operated by larger companies and included as subsidiary companies. The independent standard-gauge railways had been excluded from the Bill as a result of pressure applied by lobbying organisations.

The Welsh Highland Railway was the initiative of Evan R. Davies and Henry Joseph Jack. Both were members of the Carnarvonshire County Council, Davies, a solicitor from Pwllheli, who had been had been involved in some capacity or other in various Caernarfonshire railway schemes since 1897, and Jack the managing director of the Aluminium Corporation at Dolgarrog. Davies was a friend of the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and had worked in his private office during the war. He and Jack brought in Sir John Henderson Stewart Bt, a Scottish distillery owner, to supply funds and gravitas.

A picture postcard published by the Snowdon Mountain Tramroad in 1923, showing that it and the Welsh Highland and Ffestiniog Railways were in common ownership. (SMTH)

Evan Robert Davies (1871-1934) was a solicitor, local politician and friend of David Lloyd George. He played a key part in the development of the Welsh Highland Railway and in running the FR until his untimely death. He was also keen to promote tourism in Carnarvonshire.

Stewart’s involvement is something of a mystery as he had no obvious connection with Wales or Welsh affairs; he may not even have visited Wales. It is quite likely though, that his baronetcy, conferred in the King’s birthday honours list announced on 5 June 1920, involved a donation to a political party. In July 1920, he had attended a charity concert at 10 Downing Street and maybe he was then asked to give his support to a project being promoted by a friend of the Prime Minister, that would benefit a relatively remote area of North Wales in which the Prime Minister was interested, as quid pro quo. However, it happened: by the end of the year he was involved in Welsh narrow-gauge railways.

In November 1914, a committee of local authorities had applied for a light railway order that would consolidate the existing powers of the North Wales Narrow Gauge Railways (NWNGR), then moribund, and the Portmadoc, Beddgelert & South Snowdon Railway (PBSSR), a subsidiary of the North Wales Power Company, with assets including partially constructed earthworks around Beddgelert and the horse-worked Croesor Tramway, with the intention of completing the connection between the NWNGR and the Croesor Tramway to create a 25-mile long 2ft gauge railway from Portmadoc to Caernarfon.

The war had put the application into limbo, allowing Davies and Jack to reactivate it with the declared intention of creating jobs and facilitating tourism to a remote area as well as improving the transport infrastructure. The Aluminium Corporation held the key to the development with its acquisition of a controlling interest in the North Wales Power Company, and therefore the PBSSR assets, in 1918.

Seeking to obtain loans from the Ministry of Transport and the local authorities to fund what they came to call the Welsh Highland Railway (WHR), Davies and Jack needed additional funds to acquire the NWNGR and PBSSR assets, which seems to be the initial reason for Stewart’s involvement. They also appear to have realised that their scheme would benefit from the involvement of the Ffestiniog Railway, which had rolling stock that could be beneficial on the new railway, and a functioning workshop.

Keeping the FR out of the proposed railway grouping was therefore essential to getting the WHR off the ground, and was achieved, as already noted, by saying that there was already in existence a grouping of narrow-gauge railways, secure in the knowledge that the Great Western Railway would not want to take on the Welsh Highland.

Stewart had become active in the railways from 1 January 1921, when he acquired the NWNGR and PBSSR assets, and paid £1,500 to keep the NWNGR going. On 21 March, he acquired the majority shareholding of the Snowdon Mountain Tramroad & Hotels Company, which was, fortuitously, on the market, and on 29 March he purchased F. P. Robjent’s FR holdings, except for £1,000 ordinary stock to enable Davies and Jack to qualify as directors. Robjent, a stockbroker, had been a director since 1908.

By the end of June, Stewart held £42,999 ordinary stock, £3,660 4½ per cent preference shares and £23,340 5 per cent preference shares, not quite a majority in all classes, but enough to take control. Later in the year, Jack was to tell the Minister of Transport that it had cost £40,000 to take over the FR. Given that in December 1920 ordinary stock had been trading at 15 per cent and 5 per cent preference shares at 80 per cent, it was unlikely to have been that much.

On 15 July, £28,000 ordinary stock, £2,660 4½ per cent preference shares and £15,340 5 per cent preference shares were transferred to Jack, and £14,000 ordinary stock, £1,000 4½ per cent preference shares and £8,000 5 per cent preference shares to Davies, leaving Stewart with just £999 ordinary stock.

News that there was a takeover in the offing had obviously been the subject of gossip and speculation, for on 1 June, the Lancashire Evening Post had reported that the LNWR had bought the railway and would start to work it in August!

Jack and Davies formally took control on 16 July. R.M. Greaves, the retiring chairman, had not attended the two directors’ meeting held since March and had sold £714 10s 7d ordinary stock and £1,000 4½ per cent preference shares to Robjent on 24 June. The other directors also resigned, with Frederick Vaughan, the managing director, resigning resigning as a director and being appointed as general manager with a salary of £225. Jack was appointed chairman on 30 July. Stewart only attended directors’ meetings held in London and ceased to attend them after mid-1922.

Government control of railways ended with the enactment of the Railways Act on 19 August 1921. During 1920, a Major G.C. Spring had been commissioned to report on the condition and prospects of the NWNGR, PBSSR (including the Croesor Tramway) and the FR. Writing to Vaughan on 12 September 1921, he concluded, ‘I am afraid that I have discovered nothing that was not fully known before.’ His report ended, ‘It is fairly obvious that before further extensions are considered the Ffestiniog Railway must first be placed in a paying condition.’ It is not known who commissioned and paid for the report.

Comparing the years 1913 and 1920, Spring noted that loco mileage had increased despite a decline in traffic, attributing the difference to a reduction in the number of gravity trains run. Working expenses, 74 per cent of receipts in 1913, had risen to 160 per cent. Staff employed on the track and in Boston Lodge did not seem excessive, except for ‘the large number [five] of apprentices employed’. There were too many clerks at Minffordd. Any savings made by replacing the gates at Minffordd and Penrhyn crossings with cattle guards would be minimal as one of the keepers was a pensioner, the other a woman. The mileage of the two shunting engines was largely unproductive, especially as the top shunter was based at Boston Lodge during the winter, but its cost had to be borne by the business.

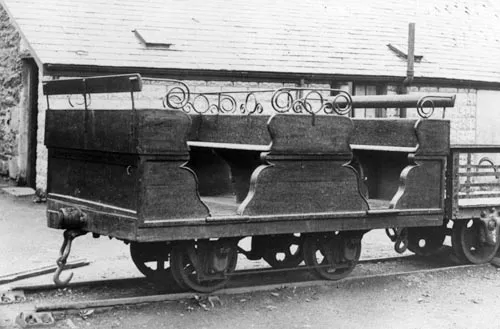

This little carriage ‘appeared’ at Boston Lodge in 1923. Probably made there, its purpose is unknown although it has been linked to the Oakeley family. Perhaps it was attached to the back of gravity trains to give visitors a thrill. It is stabled on some very old rail.

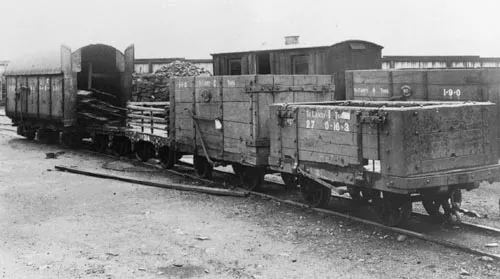

An assortment of wagons, including the six-wheeled Cleminson, and a quarrymen’s carriage at Boston Lodge.

Concerning the slate wagons, he noted that the railway had given up trying to charge demurrage on wagons that overstayed in the quarries or wharves. On the basis that the fleet was about 1,200, he allowed 12½ per cent to be unavailable for maintenance, giving 1,050 available for traffic. With a daily demand for 425 wagons, therefore, and knowing that the quarry managers complained about shortages, he concluded that they were either kept under load for disproportionate periods, that they remained in the quarries or that they were blocked in sidings by new arrivals. He had noticed that two loaded wagons descending an incline required four empties to balance them.

The maintenance of the works was ‘an expenditure out of all proportion to the mileage and stock of the railway’; either the workshops must do more outside work or be run as a separate undertaking. Time was wasted because there was no crane capable of lifting carriages off their bogies, there was no hand crane to lift wheels into the wheel lathe, there was no planing machine for the carpenters and, when heavy loco repairs were done in the loco shed and machining in the works, there was too much ‘unnecessary walking to and fro’.

Amongst Spring’s recommendations were proposals reducing the number of loco turns of more than eight hours, working on a one-engine-in-steam basis, at the expense of dislocating the service, and closing the stations with tickets sold by the guard; he also recommended terminating passenger trains at the GW station in Blaenau Ffestiniog instead of at Duffws. Whilst the FR met the criteria regarding speed and axle weight for being treated as a light railway, he thought ‘it would appear that an order to treat the Ffestiniog Railway as a light railway would not have the effect of cheapening operation’.

Vaughan had his own ideas for economies, on 26 September 1921 suggesting to E.R. Davies that stations should be closed and converted to halts. Writing from 10 Downing Street, Davies supported the idea, saying that he did not see why the proposal should be affected by the nature of the railway’s carriages and that in winter the guard could issue tickets. The idea was not pursued.

The new directors appointed C.E. Hemmings, secretary of the Aluminium Corporation in 1922-3, as assistant secretary to A.G. Crick, a clerk at Portmadoc, and the share register was transferred to his office at 4 Broad Street Place, London EC, in August. Legal work was deputed to Davies’ Pwllheli office.

James Williamson, the Cambrian Railways’ assistant engineer, was appointed engineer in succession to Rowland Jones, who had died on 13 May 1921, aged fifty-nine. He had been well regarded by the old directors, who awarded him gratuities on several occasions and minuted his passing. His son Robert was the railway’s foreman platelayer. Williamson’s salary was £130.

Stewart seems to have used his Ffestiniog stock as security for loans. In September 1921, preference shares totalling £27, 000 were transferred by Davies and Jack to the National Bank’s nominee company; they were transferred back to Stewart in November. In June 1922 Stewart transferred £7,000 preference shares and £12,000 ordinary stock to the Royal Bank of Scotland’s Dundee branch, where they stayed until December 1923.

Just what the proposals for reorganisation of the Ffestiniog and neighbouring railways were that prompted the Great Western Railway to offer the company the services of a manager, S.C. Tyrwhitt, on a temporary basis in 1921, are not known.

However, on 28 December, the directors resolved to appoint him as assistant general manager, charged with the task of negotiating with the GWR over the use of its Blaenau Ffestiniog Station as a joint station, to allow passenger services to be withdrawn from Duffws. At the same meeting, Vaughan’s submission of three months’ notice was accepted.

It turned out that Vaughan was ill; he seems to have finished work during February and died of heart failure on 6 April 1922, aged seventy; Crick was instructed to write to his widow expressing the board’s condolences. His £6,853 0s 9d (£326,500 in 2014) estate indicates that he had been well served by his railway career.

Newspaper reports during 1921 give an indication of the poor state of affairs on the railway. In April and May, bad coal was blamed for prolonged journeys, the Manchester Guardian saying that on one occasion the train stopped in a wood and passengers gathered sticks to enable it to continue. The quarrymen’s train was affected on the another occasion, the Lancashire Evening Post noting that it took two and a half hours to cover the 10 miles from Penrhyn, an average speed of 4mph.

More seriously, in February a gravity train had collided with other slate wagons at Minffordd, damaging the track and destroying a brake van. Some wagons ‘were hurled over the Cambrian Railway embankment’, the Lancashire Evening Post reported. Fortunately, no one was injured.

Palmerston prepares to leave Duffws shortly before passenger services were withdrawn.

Traffic during the year must also have been affected by a drought that closed the quarries for two weeks in July. In 1922, they were closed by a flu epidemic in February and by snow in March.

Despite Spring’s scepticism that operating the railway as a light railway would be accompanied by savings, on 6 February 1922 the directors resolved to make an application for that purpose, adding to it powers to make a physical junction with the Portmadoc, Beddgelert & South Snowdon Railway, the Welsh Highland, and for a new, joint, station in substitution for the Festiniog Railway’s existing Portmadoc Station. In their planning for the WHR, they had failed to notice that although they had acquired the PBSSR’s powers to run trains to/from Portmadoc, they did not have a direct connection with the FR, or a station in the town. As the WHR’s limited financial position gave no scope to secure additional funding, they decided to use the resources available to the FR to secure their objectives.

Williamson obviously did not impress the directors when he produced the plans required for a siding required by the Moelwyn Granite Company in the early part of 1922, for they were accompanied with a request for a fee of 5 per cent for producing them and another 10 per cent when the work was completed. On 28 February, they...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements and sources

- Introduction

- 1 1921-1924: The arrival of the Welsh Highland Railway

- 2 1925-1931: Management from Tonbridge

- 3 1932-1945: Leasing the Welsh Highland, the end of passenger services

- 4 1946-1954: Dark days of war, closure and abandonment

- 5 1955-1958: Revival – back to Tan y Bwlch

- 6 1958-1962: Traffic booms

- 7 1963-1970: Consolidation, deviation, Dduallt

- 8 1971-1977: Pursuing the dream

- 9 1978-1985: Back to Blaenau, but no pot of gold

- 10 1986-1991: 150 years, and the Welsh Highland controversy

- 11 1991-1997: Legal and lottery successes, and new locomotives

- 12 1998-2003: Turning around, running two railways

- 13 2004-2009: Outside contracts successes

- 14 2010-2014: The Welsh Highland returns

- POSTSCRIPT

- APPENDIX 1 Summary of results 1921-2014

- APPENDIX 2 Capital expenditure 1923-1929

- APPENDIX 3 Levels of debt 1965-84

- APPENDIX 4 Passenger journeys/bookings 1956-2014

- APPENDIX 5 Non-statutory directors

- APPENDIX 6 Festiniog Railway Company Directors 1833-2014

- APPENDIX 7 Festiniog Railway Trust Trustees 1955-2015

- APPENDIX 8 Deposited plans of 1923, 1968 and 1975 Light Railway Orders

- BIBLIOGRAPHY