eBook - ePub

The Battleship Builders

Constructing and Arming British Capital Ships

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How shipbuilders, engine manufacturers, and more united to build Britain's Grand Fleet: "Superbly written…One of the best naval titles I have seen."—

Marine News

The launch in 1906 of HMS Dreadnought, the world's first all-big-gun battleship, rendered all existing battle fleets obsolete, but at the same time it wiped out the Royal Navy's numerical advantage, so expensively maintained for decades. Already locked in the same arms race with Germany, Britain urgently needed to build an entirely new battle fleet of these larger, more complex, and costlier vessels.

In this she succeeded spectacularly; in little over a decade fifty such ships were completed, almost exactly double what Germany achieved. It was only made possible by a vast industrial nexus of shipbuilders, engine manufacturers, armament fleets, and specialist armor producers, whose contribution to the Grand Fleet is too often ignored. This heroic achievement, and how it was done, is the subject of this book. It charts the rise of the large industrial conglomerates that were key to this success, looks at the reaction to fast-moving technical changes, and analyzes the politics of funding this vast national effort, both before and beyond the Great War. It also attempts to assess the true cost—and value—of the Grand Fleet in terms of the resources consumed. And finally, by way of contrast, it describes the effects of the postwar recession, industrial contraction, and the very different responses to rearmament in the run up to the Second World War.

Includes photographs

The launch in 1906 of HMS Dreadnought, the world's first all-big-gun battleship, rendered all existing battle fleets obsolete, but at the same time it wiped out the Royal Navy's numerical advantage, so expensively maintained for decades. Already locked in the same arms race with Germany, Britain urgently needed to build an entirely new battle fleet of these larger, more complex, and costlier vessels.

In this she succeeded spectacularly; in little over a decade fifty such ships were completed, almost exactly double what Germany achieved. It was only made possible by a vast industrial nexus of shipbuilders, engine manufacturers, armament fleets, and specialist armor producers, whose contribution to the Grand Fleet is too often ignored. This heroic achievement, and how it was done, is the subject of this book. It charts the rise of the large industrial conglomerates that were key to this success, looks at the reaction to fast-moving technical changes, and analyzes the politics of funding this vast national effort, both before and beyond the Great War. It also attempts to assess the true cost—and value—of the Grand Fleet in terms of the resources consumed. And finally, by way of contrast, it describes the effects of the postwar recession, industrial contraction, and the very different responses to rearmament in the run up to the Second World War.

Includes photographs

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battleship Builders by Ian Johnston,Ian Buxton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: INTRODUCTION

DURING THE LAST HALF OF THE nineteenth century, a number of British industrial concerns involved in the construction of ships and the manufacture of armaments grew substantially in size, mainly through contracts from the British Admiralty and overseas governments. By the early 1900s, through a series of mergers and take-overs, these businesses had coalesced into a formidable naval construction industry comprised of vertically integrated companies employing tens of thousands in their shipyards, engine works, ordnance factories, steel works, armour mills, forges and foundries across the UK.

In 1904, the British fleet was undoubtedly the most powerful in the world, being greater than the combined fleets of the next two largest naval powers, France and Russia. In 1905 the Admiralty decided to proceed with the construction of the revolutionary battleship Dreadnought, a stratagem which effectively made their own and all other existing battle fleets obsolete. Much of this ‘pre-dreadnought’ fleet, as it was rather disparagingly termed, was of very recent construction. Indeed, the very last examples of the type, Lord Nelson and Agamemnon, were not completed until two years after Dreadnought. The eclipse of the pre-dread-noughts, created at great cost to the country, nevertheless presented an opportunity for the new armaments combines and the Royal Dockyards to construct a new battle fleet.

In many respects there was no alternative to building this new fleet as the concept of a dreadnought type ship was obvious to other naval powers. The Admiralty pre-empted other naval powers and took the initiative to create a new battle fleet comprised exclusively of the dreadnought type battleship and its larger, faster but less heavily armoured variation, the battle-cruiser. Dreadnought represented a step change in the development of the battleship because of two main technical changes employed for the first time: a uniform main armament of ten 12in guns instead of the mixed calibre armament typical of contemporary battleships, and steam turbine propulsion machinery instead of reciprocating machinery, all of which conferred significantly greater tactical advantage in the design. These developments like many others associated with armament design and manufacture were pioneered by private industry.

At a different level, the decision to proceed with Dreadnought brought with it the risk that British battleship numbers might soon be matched by rival powers. Such risks were not hard to identify as the old order of established naval powers, Britain, France and Russia, was challenged by Germany, the USA and Japan, each of which had emerged at the end of the nineteenth century as industrialised powers with worldwide political ambitions. German naval intentions to build a major surface fleet declared before the construction of Dreadnought had begun, represented the most serious political and naval challenge.

Germany had grown rapidly in industrial and economic power since unification in 1871 and by 1900 had overtaken Britain in key industrial measures, such as steel production. Whilst previously British shipbuilders had constructed many merchant ships for German owners, now a large and technically advanced shipbuilding industry, coupled with a system of naval Dockyards and the Krupp armaments firm, had been created in Germany. This challenge had already been demonstrated in the mercantile marine by the construction of large, fast Atlantic liners which had, by 1902, pushed British ships into second position in terms of size and speed on the prized North Atlantic crossing. The architect of Germany’s rise as a sea power was Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz whose ambitions mirrored the grandiose imperial

aspirations of Kaiser Wilhelm II. In 1897 the enactment of the first of Tirpitz’s naval laws made it clear that Germany was determined to challenge British hegemony of the seas.

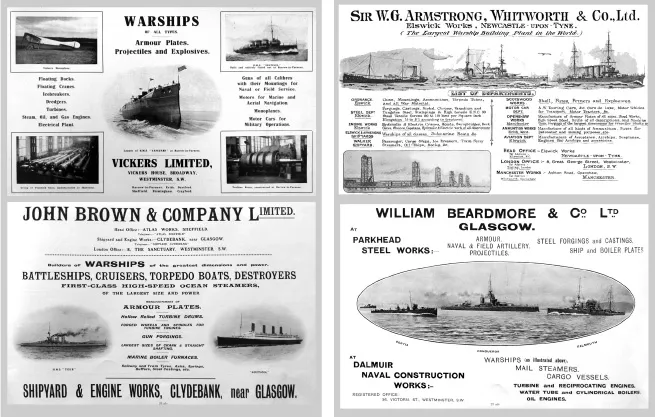

The private firms that contributed towards the construction of the battle fleet were household names as well as major employers in districts throughout the UK. (Author’s collection)

To make Dreadnought’s appearance on the world stage an unchallenged fait accompli, she was built in the record time of fourteen months at Portsmouth, drawing on the collective experience of that Dockyard, the armaments industry and turbine manufacturers to create this apparently effortless demonstration of British industrial expertise. A race had begun, later referred to as the Anglo-German naval race, which was as much to do with industrial capacity as it was with political aspiration and domination of the high seas.

The subsequent construction of the battle fleet in just ten years demonstrated the resourcefulness and capacity of British industry. Including Hood, laid down in 1916 but not completed until 1920, this totalled fifty-one ships, a remarkable total considering the great volume of merchant and other naval ships produced by the same yards in the same period. This achievement was made possible by the collective efforts of shipyards, engine works, armour and steel works, ordnance factories and a myriad of other manufacturers which drew deeply from the heart of industrial Britain. The advertisements in any pre-First World War Jane’s Fighting Ships bear witness to these now long gone businesses.

During this period, when the naval race was underway, industrial capacity was continually extended to meet the unprecedented demands placed upon it. Investment was made in new tools and plant by the companies and later by the Government in the form of munitions factories and finance during the war. By 1918, the scale of British capacity to construct warships stood at an all-time high and one that it would never reach again. At the same time, the need to construct battleships became less important as it was clear that Britain had a significant lead over German numbers.

The end of the war brought with it a wholly understandable but abrupt end to naval contracts. The political map was redrawn and the German fleet, interned at Scapa Flow, was soon to disappear in an act of self-immolation. There was to be no respite for the Admiralty however, as a new naval race between the USA and Japan demanded a response. Since the middle of the First World War, both the US and Japanese governments had backed major fleet construction programmes which by 1918 were

well established. Compelled by its strategic outlook and with the world’s largest navy, the Admiralty was obliged to consider a new round of capital ship construction.

The rapid development of capital ships from Dreadnought to Hood resulted in ships of exceptional offensive and defensive capabilities on hulls of great length and displacement. Size alone brought an end to the Royal Dockyards’ role in the construction of capital ships, no longer able to accommodate such large hulls. Henceforth, the requirement for capital ships would have to be met exclusively by private industry. The same constraints applied also to the private yards however, and those capable of constructing these very large warships were reduced to a handful. Contracts for the first of these ships, four G3 battlecruisers, were placed in 1921 and offered a lifeline to the armaments companies for whom times had become lean with survival threatened. Political intervention in the form of the 1921 Washington Treaty of Limitation prevented this new arms race from continuing and placed a ban on the construction of new capital ships for ten years, subsequently extended for another five. Despite the political and economic wisdom of this initiative, the cancellation of the G3s in February 1922 was a severe blow to a British armaments industry with a capacity now grossly in excess of demand.

In addition to halting new construction, the Washington Treaty required the reduction of fleets to agreed numbers which meant reducing the size of the British fleet to that of the US Navy. And so began the scrapping of much of the battle fleet on which so much effort, material and expenditure had so recently been spent. Only the most modern classes of battleship and battlecruiser were retained as ship-breaking yards extracted monetary values from ship material representing the merest fraction of original construction costs.

Inevitably, the industry that had produced the battle fleet was subject to a fate not dissimilar to that of the once nationally revered ships themselves. Despite attempts at diversification into peacetime production, plant lay idle or underutilised, while many companies haemorrhaged financially throughout the depressed years of the 1920s and early 1930s, forcing rationalisation and restructuring, notably the merger of Vickers and Armstrong at the end of 1927. This period saw the most significant contraction of British heavy industry in modern times and importantly the loss of skilled manpower to other industries and emigration. Efforts were made to retain key technologies and core manufacturing capacity as strategic assets such as armament design and heavy armour manufacture for which there was little demand in the 1920s, by rationalisation and a trickle of orders for cruisers.

The armaments industry, which had become inextricably linked with the shipbuilding industry through vertical integration, was subject to accusations of fomenting wars and anti-competitive practices in pursuing self-interest at various periods during the history described here. This came to a head in 1935 with the appointment of a Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms to examine such accusations. The Commission came to the realistic conclusion that private manufacture was necessary, and indeed the overwhelming need to re-arm the country in the face of rampant militarism abroad had, by the time the Commission reported in 1936, made it a somewhat moot issue in any case.

Re-armament in 1936 assisted in pulling industrial Britain out of recession. With few if any profits generated during the depressed years, little had been invested on industrial infrastructure, plant and machinery and thus Britain approached the Second World War with an armaments and shipbuilding industry little changed from 1918 in type of facility, albeit smaller in capacity. While the global strategic role of the Royal Navy had not changed, as a consequence of Washington, it was now equal first with the US Navy and battleships, although even then considered by some as an endangered species, were still the primary unit of offensive power. In 1936 after the eclipse of the limitation treaties, and the resumption of battleship building by the leading powers, the Admiralty moved as quickly as possible to place contracts for five units of the King George V class. These 35,000-ton ships which had been designed in accordance with Treaty conditions were followed in 1938 and 1939 by four larger Lion class battleships. However, the limited resources available to complete these ships meant that two of the King George V class were completed late while the Lion class, although ordered, could not be built at all because of limitations in main armament construction, other wartime priorities and a lack of shipyard labour. Vanguard, last of the British battleships, was made possible only because of the availability of existing but modernised 15in main armament mountings.

2: AN UPWARD TRAJECTORY, 1860 TO 1919

IT IS PERHAPS UNSURPRISING THAT the British shipbuilding industry was for over 100 years the world’s largest, given Britain’s position as the first developed industrial nation. The rising demand for manufactured products of all kinds, made accessible by the development of railways, stimulated trade and encouraged the rapid growth of industry across the UK. The creation, protection and maintenance of the British Empire and worldwide trade was made possible by the twin elements of seapower, the Royal Navy and merchant marine, and therein lay the foundation and success of the modern private shipbuilding industry from the mid-1800s onwards. This success was based on steam power as a prime mover and iron, later steel, as a constructional material. Prior to this, Britain was a leading builder of wooden ships and it was in this tradition that the Royal Navy’s ships were constructed in a number of Royal Dockyards concentrated around the southern half of the country.

However, in the modern era of steam and iron, the Admiralty began to place orders with the new private shipyards which, driven by commercial considerations, were pioneering the latest methods of construction and propulsion in the highly competitive building of merchantmen. By contrast, the Royal Dockyards were steeped in traditional ways of working and much slower to react to change. This was most obviously the case with the ground-breaking, all-iron, steam-propelled warship Warrior which entered service in 1861. Her construction was in response to the French Gloire, the first seagoing armour-clad, which created great unease at the Admiralty when they were made aware of her construction in 1858. The contracts for Warrior and her near sister-ship Black Prince were given to private yards skilled in iron construction and steam propulsion, as such sophisticated ships could not have been built by the Royal Dockyards in the time required, still building only in wood. In making such a swift and decisive response to the French ship, the Admiralty was making use of the already significant resources that private British industry offered.

As the private shipbuilding industry began to expand during the last half of the nineteenth century, more commercial shipyards were encouraged into warship construction, including exports, although the Royal Dockyards retained a major share; figures in early 1890s suggest about 60 per cent. During this period the battleship as a distinct warship type began to emerge through a series of design iterations where various new technologies, armament and protective systems were tried out. This process resulted in the fundamental characteristics that would define the battleship as the ultimate seaborne weapon of offence and the measure by which all navies would come to be assessed.

In 1884 concerns over the preparedness of the navy, its organisation and equipment, began a process of naval reform which reached its climax in 1889 with the passing of the Naval Defence Act. In addition to providing for a large increase in the size of the navy, the Act formalised the ‘Two Power Standard’ which required the navy to be maintained at a size equal to or greater than the combined strength of the next two largest navies, at that time France and Russia. Although this had been the de facto ambition for many decades, it had not always been met. Enshrining the Two Power Standard in law effectively committed the Admiralty to a continued process of ship construction. The Act planned ten new battleships and sixty other warships costing £21.5 million, with £11.5 million or 53 per cent planned for the Royal Dockyards.1 This was complemented by the Naval Works Act of 1895, which financed a large expansion of the Dockyards, including extensions at Portsmouth and Devonport.

The main centres of battleship production in the UK, giving some idea of the distances to be covered when transporting machinery, mountings and guns from the point of manufacture to the shipyards.While material such as steel plate and armour could be moved by rail, coasters were especially adapted to transport gun mountings from Barrow and Newcastle to shipyards and Dockyards. All material and manufactures had to be shipped to Belfast. Chatham and Pembroke are included for pre-dreadnought output and Rosyth for its role in completion work on First and Second World War battleships.

A little over a decade after the formal adoption of the Two Power Standard, Germany, unified in 1871, emerged as a significant industrial power, determined to exert political influence worldwide and take what it regarded as its rightful place in the world, as had the British, French and other colonial powers before it. The key to achieving this was seapower and, conveniently a handbook for how this should be done entitled The Influence of Seapower Upon History had been published in 1890 by Alfred Thayer Mahan, a captain in the US...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1: Introduction

- CHAPTER 2: An Upward Trajectory, 1860–1919

- CHAPTER 3: Retrenchment and Revival, 1920–1945

- CHAPTER 4: The Builders

- CHAPTER 5: Building

- CHAPTER 6: Facilities

- CHAPTER 7: Powering

- CHAPTER 8: Armament

- CHAPTER 9: Armour and Steel

- CHAPTER 10: Exporting Battleships

- CHAPTER 11: Money

- CHAPTER 12: Manpower

- CHAPTER 13: Conclusions

- APPENDICES 1: Tenders 1905 to 1945, John Brown & Co Ltd

- APPENDICES 2: Armour, the Admiralty and Parliament

- APPENDICES 3: The British Battleship Breaking Industry

- Notes

- Sources and Bibliography

- Index