![]()

Contents

| | Foreword |

| 1 | First Contacts: 1911–1914 |

| 2 | Blunders and Disasters: 1914–1915 |

| 3 | Dismissal: 1915 |

| 4 | Excluded: 1915–1917 |

| 5 | Recall: 1917–1918 |

| 6 | The Transition to Peace: 1919–1929 |

| 7 | Out of Office but Active: 1929–1939 |

| 8 | Return to Power and the

Norwegian Campaign: 1939–1940 |

| 9 | The Admirals Afloat.

I. Home Waters and the Atlantic: 1939–1942 |

| 10 | The Admirals Afloat.

II. The Mediterranean: 1940–1942 |

| 11 | The Indian Ocean and the Far East: 1941–1943 |

| 12 | The Mediterranean: 1943–1944 |

| 13 | Home Waters and the Atlantic Battle 1943–1944 |

| 14 | The Indian Ocean and the Far East: 1944 |

| 15 | The Months of Victory:

January–August 1945 |

| | Conclusion |

| | Appendix: A Historical Controversy |

| | Notes and Sources |

| | Index |

![]()

Foreword

In 1949 I was appointed to the Cabinet Office Historical Section to write the volumes of the United Kingdom Military History Series published as The War at Sea 1939–1945 (HMSO 1954–61) under the editorship of the late Professor Sir James Butler. Though often referred to colloquially as the ‘official histories’ of World War II that description is in fact incorrect, as anyone who troubles to read the Editor’s Preface to my first volume can easily ascertain, since the organization and conditions under which the Military History Series was written are there clearly described.

After some months devoted to ‘reading myself into’ the subject I was required to handle, and to studying the archival material available, I asked the Admiralty for access to the First Lord’s and First Sea Lord’s papers of my period. I did this as a test case regarding the guarantee of full and free access to all relevant documents promised to the authors of the Military Histories, since, largely thanks to Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, I was fully apprised of the serious troubles Sir Julian Corbett had experienced with the Admiralty over his volumes of the Official Naval History of World War I. Although, perhaps too imaginatively, I visualized the flurry of embarrassment which my request for such closely guarded records caused among the civil servants across the Horseguards Parade, the papers were made available to me – after some delay. I have here used them – or the survivors from among them – again, though more extensively and with greater freedom than was prudent a quarter of a century ago.

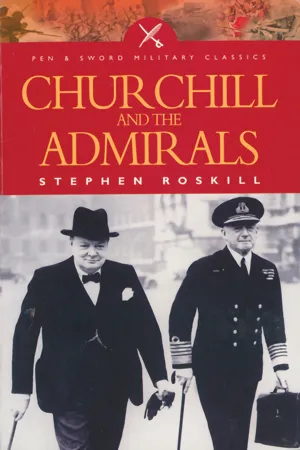

In 1949 I also got into touch with all the leading naval men of my period. Their response was without exception extremely helpful and cordial, they all agreed to read and criticize the drafts of chapters describing events in which they had taken part, or of which they had special knowledge, and they sent me a large number of valuable letters in amplification of the official records of those events. Later on some of those officers either appointed me as their literary executor, or reserved their papers and diaries for my sole use, or made Churchill College, Cambridge, of which I became a Fellow in 1961, the repository for their own collections of documents and letters. Not surprisingly a good deal of my correspondence with them dealt with the ever-fascinating subject of their relations with Winston Churchill both as First Lord of the Admiralty and as Prime Minister; and many of those officers continued to correspond with me on that subject to the day of their deaths. One end product of this correspondence, and of the prolonged thought I gave to the subject, was a series of articles published in the Sunday Telegraph in February 1962 entitled ‘Churchill and his Admirals’. (The use of the possessive pronoun was of course incorrect, as correspondents hastened to point out, since all officers held their commissions from the Monarch and not the Prime Minister, and Flag Rank was conferred by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. In my typescript I had used the definite article ‘Churchill and the Admirals’, but for some reason best known to himself the Editor altered it before printing). Despite this gaffe the reception accorded by naval men to those articles was very warm, and some of them sent me supplementary material on the subject. I thus came to accumulate a considerable archive, to which I have continuously added the fruits of further correspondence and interviews.

It was actually my Publisher’s Editor for many years Mr Richard Ollard, to whom I owe an immense debt for historical and literary guidance, who suggested that I should expand the Sunday Telegraph articles into a book; and the work now presented to the public, not without a good deal of diffidence on my part, is the result.

It is I think essential to make clear that one of the chief sources I have used, namely the minutes, memoranda and letters which Churchill addressed to the Admiralty (generally to the First Lord and First Sea Lord), and the replies sent to him were produced in totally different ways. As to the former, though Churchill sometimes acted on advice or suggestions made to him by the members of his ‘Secret Circle’ or Inner Cabinet, they nearly all bear the unmistakable and inimitable mark of his own style, and were probably dictated directly from the ever-active volcano of his mind. The replies on the other hand, though generally signed by A. V. Alexander the First Lord or, less commonly by the First Sea Lord, were in essence the considered view of the naval staff. When one of Churchill’s minutes, often referred to colloquially as ‘prayers’ because of his custom of beginning them with a request such as ‘Pray consider’ something or other, arrived in the Admiralty it would first go to the staff division or supply department chiefly concerned, and a reply would be drafted there. If it bore one of his ‘Action This Day’ labels it would next be taken by hand to any other staff division concerned, where additions or amendments might be made, and then to the member of the Board of Admiralty or ‘Superintending Lord’ responsible for that particular aspect of the navy’s administration or operations. Again amendments might be made before it was taken, again by hand, to the offices of the VCNS and First Sea Lord, from which, if they approved the draft, it would be cleared with the branch of the Secretariat concerned and then taken to the First Lord’s Private Office. Although in cases of extreme urgency some of the above steps might be cut out such was the practice generally followed; and it is noteworthy that the First Sea Lord and First Lord usually accepted the drafts which reached them – perhaps making some minor amendments. I have found few cases where they disagreed so fundamentally that the proposed reply was sent back down the line for review and reconsideration. Thus the Admiralty’s answers, though usually well expressed and clearly worded, strike quite a different note to that sounded by the Churchillian minutes they were answering, and one does not find in them the picturesque metaphor and graphic phraseology, let alone the occasional hortatory or minatory note, which characterized the latter. The difference lay of course in the fact that whereas the minutes were the product of a brilliant, if sometimes erratic, mind the answers had to represent the less distinctive but carefully considered departmental view. A similar difference will be found between the many signals and letters Churchill addressed direct to Commanders-in-Chief of the major fleets or, less frequently, to commanders of squadrons, and for the same reasons but with the Flag Officers’ staff acting in place of the naval staff in Whitehall.

In the case of Churchill’s more formal letters and telegrams, and especially those of political or diplomatic significance, though he often prepared a first draft himself for circulation to the Ministers and Officials concerned, he sought, and often accepted amendments which they suggested. Where the first draft was prepared in one of the departments he commonly made amendments in his own hand; but the proposal or answer as finall...