- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When the world held its breath It is more than 25 years since the end of the Cold War. It began over 75 years ago, in 1944 long before the last shots of the Second World War had echoed across the wastelands of Eastern Europe with the brutal Greek Civil War. The battle lines are no longer drawn, but they linger on, unwittingly or not, in conflict zones such as Syria, Somalia and Ukraine. In an era of mass-produced AK-47s and ICBMs, one such flashpoint was Hungary Soviet troops had occupied Hungary in 1945 as they pushed towards Germany and by 1949 the country was ruled by a communist government that towed the Soviet line. Resentment at the system eventually boiled over at the end of October 1956. Protests erupted on the streets of Budapest and, as the violence spread, the government fell and was replaced by a new, more moderate regime. However, the intention of the new government to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and declare neutrality in the Cold War proved just too much for Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.Soviet forces had intervened at the beginning of events to help the former regime keep order but were withdrawn at the end of October, only to return in November and quell the uprising with blunt force. Thousands were arrested, many of whom were imprisoned and more than 300 executed. An estimated 200,000 fled Hungary as refugees. Despite advocating a policy of rolling back Soviet influence, the US and other western powers were helpless to stop the suppression of the uprising, which marked a realization that the Cold War in Europe had reached a stalemate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hungarian Uprising by Louis Archard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. HUNGARY BECOMES A PEOPLE’S DEMOCRACY, 1944–53

In late 1944 and 1945, as the Allies advanced and the forces of Nazi Germany were pushed back, there was a feeling of rebirth and beginning again across Europe. In German, they called it Stunde null – Zero hour, the moment at which the fighting passed on, silence fell and the war was finally over – but the feeling was common across the continent.

Many Hungarians had believed that their country would be liberated by British or American forces advancing from the West as it was too geopolitically significant to leave to the Russians. However, despite this belief it would be the Red Army that pushed Nazi Germany out of Hungary from autumn 1944 onwards. On 29 October 1944, troops of the 2nd Ukrainian Front, commanded by General Malinovsky, began their offensive against Budapest itself. Soviet and Romanian troops entered the city’s eastern suburbs on 7 November and when, on 26 December, the last road linking Budapest with Vienna was cut, the Hungarian capital was surrounded. Hitler had declared Budapest to be a fortress city, to be defended to the last man. The siege would last for fifty-one days.

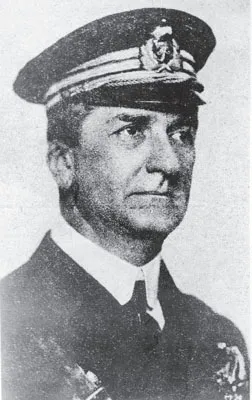

Before the Second World War, Hungary had been ruled by Miklós Horthy. Horthy was a former admiral in the Austro-Hungarian Navy who had come to power in the period of instability that followed the defeat of the Habsburg Empire in the First World War, restoring order after the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic under Béla Kun and its subsequent defeat by a Romanian army.

Although Horthy initially banned both the Hungarian Communist Party and the fascist Arrow Cross, Hungary became increasingly closely aligned with Nazi Germany for economic reasons, as a protection against Soviet communism and because Hitler tore up the settlements that had been put into place in eastern and central Europe as a result of the peace treaties that ended the First World War. Having been part of the Habsburg Empire, one of the Central Powers along with Germany and the Ottoman Empire, and seen as one of the aggressors that had started the war, territory that had belonged to the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary was given to some of the new nation states that emerged from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Transylvania, for example, had previously been part of Hungary but after the war representatives of its ethnic Romanian majority declared union with Romania and this was confirmed in the Treaty of Trianon between the victorious Allied powers and what had been Austria-Hungary. A desire to regain the territories lost at Trianon was an important part of Hungarian life between the First and Second World Wars.

Hungarian troops joined the Axis war effort formally in June 1941, sending troops and resources to help in Operation Barbarossa and declaring war on the Soviet Union on 27 June, five days after the German invasion began. Enthusiasm for the war in Hungary, however, was never high and suffered a serious blow when the Second Hungarian Army was nearly obliterated by the Soviets in January 1943 as part of the fighting around Stalingrad, at a cost of nearly 80,000 Hungarian dead.

Admiral Miklós Horthy in 1921. Horthy came to power during the instability that gripped Hungary following the end of the First World War and ruled until he was deposed on Hitler’s orders in October 1944. (Library of Congress)

By 1944, as an eventual Allied victory was looking increasingly likely, the Horthy government began to approach the Allies about a separate peace settlement, hoping to save the country from Soviet invasion and occupation. Hitler, furious at this betrayal, ordered German troops to invade and occupy Hungary on 19 March. Horthy was allowed to remain in place as Hungary’s leader but the Hungarian government was effectively under German control. As the military situation continued to deteriorate, Horthy made another attempt to negotiate a separate peace in September; this came to German attention and this time the Germans seized Horthy’s son as a hostage and on 15 October, as the Soviets were preparing their offensive against Budapest, forced the Admiral to abdicate in favour of the Arrow Cross leader, Ferenc Szálas. The Arrow Cross was a Hungarian political movement similar in ways to the Nazi Party in Germany (both were anti-Semitic and both believed in the idea of ‘master races’), although there were differences and disagreements between the two as well.

By the time the Germans had replaced Horthy with Szálas, however, Hungary’s post-war fate had already been determined. Churchill had gone to Moscow for discussions with Stalin. On 9 October, the two men met and agreed the so-called Percentages Deal, which allocated proportions of post-war influence in various countries between Britain and the Soviet Union. In this meeting Churchill effectively traded Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe for British dominance in Greece, then in the throes of its civil war between communist guerrillas and the British-backed government. Influence in Hungary would be split equally between Britain and the Soviet Union, 50/50. The two leaders sketched out their arrangement on a piece of paper and when they were done Churchill said to Stalin, ‘Might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an offhand manner? Let us burn the paper?’ Stalin, less troubled by qualms, responded, ‘No, you keep it.’

The next day, British foreign secretary Anthony Eden met with the Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov. Molotov informed Eden that ‘Marshal Stalin thought that after learning of the considerable losses sustained by the Red Army in Hungary, the army would not understand it if a principle of 50/50 were allotted.’ He went on to inform Eden that ‘the 75/25 principle was what the Soviet Government proposed, for the reason that Hungary bordered on the Soviet Union and the Red Army was operating in that country and suffering losses’.

Back in the summer of 1941, even before Hungarian troops had joined the assault against the Soviet Union, Hungarian territory had been used as a jumping off point for Operation Barbarossa, as had Romania and German-occupied Poland. Stalin would not forget this – so far as he was concerned, the USSR’s neighbours to the west were a potential threat and would need to be neutralized as part of a Soviet sphere of influence to prevent them posing a threat again. In a meeting with Anthony Eden in October 1944, Molotov told him, ‘Hungary had been and always would be a bordering country. Russia’s interest was therefore comprehensible. Russia did not want Hungary to be on the side of the aggressor in the future.’

Despite his agreement with Churchill, Stalin had never intended to allow the Western Allies any meaningful role in the post-war occupation and administration of Eastern Europe. Churchill and President Roosevelt would later be accused of selling out Eastern Europe to the Soviets, but in reality there was very little that could be done short of a war for which there was no appetite: by the time of the Yalta Conference, at which the future of post-war Europe was to be decided, Eastern Europe was occupied by millions of Soviet soldiers. As early as 1942, Stalin had told Molotov, ‘The question of borders will be decided by force.’ So far as the Soviet leader was concerned, Churchill’s percentages deal was nothing more than an attempt to haggle over something which had already happened. Churchill himself entertained no illusions about Britain’s ability to force the Red Army out of the territory it had occupied. Instead, he had hoped that through acceptance of the situation in Eastern Europe, he might be able to save Greece, which had been Britain’s ally earlier in the war, and also preserve British influence in the Mediterranean and protect the route to Britain’s empire in the Far East via the Suez Canal. Roosevelt, meanwhile, was keen to ensure Soviet cooperation in the formation of the United Nations and the new post-war settlement that he hoped would prevent another world war; he also wanted Soviet help in dealing with the Japanese forces in Manchuria and the use of bases in the Soviet Far East to support a possible amphibious invasion of the Japanese Home Islands.

Stalin’s goal was to end the war having regained control of Soviet territory that had been conquered by the Germans. In addition, he wanted the territories ceded to the Soviet Union in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that had been signed with Nazi Germany in 1939 (the Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia and parts of Finland, Poland and Romania) and a sphere of influence that covered the countries that immediately bordered the Soviet Union to the west. This, he thought, would appropriately reflect the scale of destruction and loss of life inflicted on the Soviet Union during the war. It would also help to insure the future security of his rule by preventing enemy forces from gathering on the borders of the USSR itself, as they had done in the summer of 1941. Although the Soviet excuse for denying the Western Allies any influence in the occupation of those countries in Eastern Europe that had been allied to Nazi Germany (Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria) was that the USSR had been excluded from the negotiations over the surrender of Italy, it seems unlikely that Stalin ever intended to allow anything other than Soviet domination of the region.

The German invasion had been the greatest crisis of Stalin’s life. When the first news of the invasion arrived at the Kremlin, Stalin at first refused to believe that Hitler had ordered it. He suggested that it might have been a provocation by German officers and that Hitler might not be aware of it, although the formal declaration of war by the Germans later that morning soon persuaded Stalin otherwise. Although there would be a great deal of bad news over the following days, the full effects of the disaster that was befalling the Soviet Union seem to have really hit Stalin on 28 June when news arrived that the Germans had captured Minsk, 300 miles into Soviet territory. On his way out to his dacha at Kuntsevo after meeting with the military commanders, Stalin is said to have told his companions, ‘Everything’s lost. I give up.’ The next day, Stalin did not turn up for work but stayed out at Kuntsevo and nobody could get in touch with him. Stalin did not appear the day after that either and eventually that evening a delegation led by Molotov, the secret police chief Beria and Mikoyan, responsible for trade and supply, went out to the dacha. When they arrived, according to one account, Stalin looked at them and asked, ‘Why have you come?’ Mikoyan believed that Stalin had thought they had come to arrest him. Instead, Beria suggested forming a State Defence Committee headed by Stalin, and Stalin agreed.

Simon Sebag-Montefiore, in his account of Stalin and his court, has interpreted this as a combination of a genuine nervous breakdown on Stalin’s part and a performance, intended to test the loyalty of his followers and allow the Politburo to re-elect him to his position. Stalin seems to have been unsure of how events would unfold when his colleagues arrived and although a line was drawn under the disastrous conduct of the war until that point, the Soviet dictator would not forget what had happened or those who witnessed it. ‘We were witnesses to Stalin’s moments of weakness,’ observed Beria. ‘Joseph Vissarionovich will never forgive that move of ours.’

Although the arrival of the Red Army in Hungary was presented as liberation by Soviet propaganda, those who witnessed it for themselves often felt it was a mixed blessing. There were immediate outbreaks of rape and violence committed against civilians by Soviet soldiers. This caused despair even among the local communists, who understood all too well how effective it would be at turning people against the Soviet system. There was also looting, both on an individual scale by Soviet soldiers and on a larger scale as official and unofficial reparations for the damage caused by the war in the Soviet Union. This was despite the destruction that had been inflicted in Budapest especially by the fighting.

Three-quarters of the buildings in Budapest had been destroyed – 4 per cent had been totally destroyed, while only 22 per cent had been left habitable. The city’s population, meanwhile, had been reduced by a third. In 1945/46, Hungary’s Gross National Product was half that of 1939 and 40 per cent of the country’s economic infrastructure had been destroyed. When the Germans retreated, they took a large proportion of Hungary’s railway rolling stock with them, and a lot of what remained would be taken by the Soviets as war reparations, or what Hungarians termed ‘official looting’. According to the peace treaties that officially ended the Second World War, the Soviet Union was entitled to all the German-owned property in Hungary as compensation for the destruction that had been inflicted by the Germans. About one-third of Hungarian industry could be described in this way, with the result that 200 complete factories, together with the machinery from 300 more, were dismantled and shipped back to the USSR. Entire sectors of the Hungarian economy were taken over wholesale by the Soviets: transport, electricity, steel production, coal mining, the oil industry.

As well as reparations in kind, there were also cash payments to be made. Hungary was obliged to pay $200 million in official war reparations to the USSR, along with $50 million each to the governments of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, at pre-war 1938 prices. In addition to this, the Soviets had taken one-third of Hungary’s reserves of gold and silver bullion back to the USSR. A United Nations estimate suggested that 40 per cent of Hungary’s national income was swallowed up by looting, reparations and other costs imposed by the Soviet occupation. Partly due to this burden, and partly to the latest in a succession of bad harvests in the countryside, the Hungarian currency collapsed in August 1945 and Hungary suffered some of the worst hyperinflation ever recorded. The crisis was only resolved when the pengő was replaced in August 1946 by a new currency, the forint, backed by $40 million in gold reserves that had been taken to Germany late in 1944 and then recovered and returned by the United States.

The view west from Buda Castle (then known as the Royal Palace) towards Krisztina Boulevard in 1945, showing the damage that had been sustained during the fighting for Budapest at the end of 1944. (Fortepan: Glázer Attila)

A view along the eastern embankment of the Danube, showing the remains of the Margit Bridge and a number of steamers that had been sunk at their moorings. (Fortepan: Fortepan)

A man walks past one of the piers of the Lánchíd or Chain Bridge, the first permanent bridge across the Danube in Hungary. All of the bridges across the Danube in Budapest were blown up by German military engineers in the hope of slowing the Soviet advance. Note the ice on the river, which indicates that this is early 1945. (Fortepan: Glázer Attila)

Another view of the Lánchíd, looking from the eastern Pest side of the river across to Buda. This shows more clearly the thoroughness with which the German engineers had done their job in 1944. (Fortepan: Fortepan)

On 4 November 1945, Hungarians went to the polls to choose their new government. Six parties fielded candidates in the election, and of these five won seats in Parliament: the Independent Smallholders, Social Democrats, Communists, National Peasants and the Democratic Party. By far the biggest share of the vote went to the Independent Smallholders, traditional representatives of landholders and the bourgeoisie, who won 57 per cent of the vote and 245 seats. The Social Democrats won 17.4 per cent and sixty-nine seats, the Communists 17 per cent and seventy seats. This came as an unpleasant surprise to both the communists and their Soviet backers; the communist leader, Mátyás Rákosi, had predicted a triumph for his party and with a surprising degree of courage blamed the defeat on the public connecting the communists with the raping and looting of Soviet troops.

In a shattered Eastern Europe looking to rebuild itself after the destruction of the war years, communism was not unpopular with ordinary people – it was utopian and it offered an alternative to the pre-war governments that people blamed for involving them in the war. However, Hungary was not fertile ground for the communists despite the right-wing Horthy regime and the German occupation that had followed it. There were no inducements from Moscow that the party could offer the electorate to make up for the negative things with which communism and the USSR were associated. In Poland and Romania, for instance, the communists could point to favourable border changes but Moscow was unwilling to discuss a similar arrangement for Hungary. In addition to this, the communist presence in Hungary before the war had been small.

The Hungarian Communist Party had been banned by Admiral Horthy following the chaos that had resulted from Béla Kun’s short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic. However, it remained in existence unofficially and underground throughout the years that followed, re-emerging into the open following the arrival of Soviet troops and moving into new offices in central Budapest, in the building that had formerly been the Gestapo’s headquarters in the city. The Kremlin also sent some 300 Hungarian communists to accompany the Red Army into the country; these so-called ‘Moscow communists’ (as opposed to those who had been in Western Europe or ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Chronology

- Author’s Note

- 1. Hungary Becomes a People’s Democracy, 1944–53

- 2. Liberalization and Building Tension, 1953–October 1956

- 3. Uprising Part One, 23–29 October

- 4. Uprising Part Two, 30 October–4 November

- 5. International Reaction and Aftermath

- Bibliography

- About the Author

- Plate section