eBook - ePub

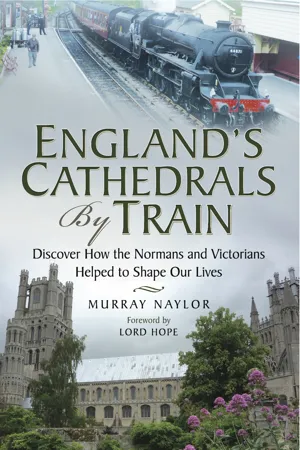

England's Cathedrals by Train

Discover how the Normans and Victorians Helped to Shape our Lives

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

England's Cathedrals by Train

Discover how the Normans and Victorians Helped to Shape our Lives

About this book

One of the jewels in the nation's crown is its Anglican cathedrals. Many, constructed after the invasion of 1066, stand as monuments to the determination and commitment of their Norman builders. Others have been built in later centuries while some started life as parish churches and were subsequently raised to cathedral status. Places of wonder and beauty, they symbolize the Christian life of the nation and are more visited today than ever as places which represent England's religious creed, heritage and the skills of their builders.Eight hundred years later came the Victorians who pioneered the Industrial Revolution and created railways. Like their Norman predecessors they built to last and the railway system bequeathed to later generations, has endured in much the same form as when originally constructed. There is little sign that railways will be displaced by other modes of transport, anyway in the foreseeable future,Combining a study of thirty-three English cathedrals and the railway systems which allow them to be reached, the author seeks to celebrate these two magnificent institutions. In the process he hopes to encourage others to travel the same journeys as he himself has undertaken.As seen in The Church Times and Worcester News.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

East Anglia

Lincoln Cathedral.

Chapter 17

Lincoln and Peterborough

■ Lincoln Cathedral ■ the importance of St Hugh ■ some less frequented railways of East Anglia ■ Peterborough Cathedral ■ where two queens were buried ■ the world speed record for a steam locomotive ■

Getting There

Direct train services from London to Lincoln are very few considering the importance of the city and not necessarily convenient to the traveller. However, by taking an East Coast mainline express to the north and changing into a connecting service at Peterborough, Newark or Doncaster, Lincoln can be reached in less than two-and-a-half hours from London.

Peterborough is fifty minutes from King’s Cross; Newark about seventy-five minutes and Doncaster around an hour and a half. The onward journey to Lincoln from Newark is less than an hour; from Peterborough and Doncaster it is over an hour.

The journey connecting Lincoln to Peterborough via Sleaford and Spalding takes one hour and twenty minutes.

Railway Notes

Visits to Lincoln and Peterborough were amongst the first undertaken in researching this book and I chose to journey to the two cities by going first to Lincoln via a change at Doncaster, and then to Peterborough. I travelled between the two cathedrals by a route originally managed jointly by the Great Northern and Great Eastern Railway companies prior to the 1923 Act of Parliament that incorporated both into the London & North Eastern Railway. I chose this route because it offers more of interest to the railway enthusiast. There are alternative routes to both cathedrals as set out at the head of this chapter, all of which are equally convenient. It is feasible to visit both cathedrals in one day, although it will be a long one.

Doncaster is a bleak and austere station with little to recommend it other than the multiplicity of services that call there giving connections across the country. Journeying eastwards from the town the train to Lincoln first travels towards the river Trent, Middle England’s largest river, which it crosses at Gainsborough, an inland port dominated by an enormous power station. The flat landscape gets flatter and seemingly wetter the closer you get to Lincoln. The cathedral stands high above the surrounding countryside on a limestone ridge, suggestive of a ship stranded upon a rocky foreshore, and can be seen from all directions long before the city is reached. When floodlit at night it presents an even more imposing sight.

York Station. An example of one of the many impressive railway stations built in Britain in the twentieth century.

The splendid Gothic cathedral, built in the twelfth century, dominates the city and surrounding countryside and is one of England’s earliest Norman churches.

Look for the west front with its frieze, the spacious area and the pillars of the nave, the Bishop’s Eye and the Dean’s Eye in the transepts, St Hugh’s Quire and the Lincoln Imp on the north side of the Angel Quire.

Apart from the distant prospect of the cathedral there is little to tell a visitor that he is approaching one of Christendom’s most glorious churches as his train nears the city. Lincoln itself is not an attractive place. Moreover, reaching the Cathedral Quarter from the station involves a twenty-minute walk up a hill that becomes progressively steeper the higher you climb. However, the climb is well worthwhile since Lincoln Cathedral has much to show the visitor.

Like so many places in Britain early attempts to establish a centre of worship at Lincoln were curtailed by disaster. The first bishop, Remigius, instructed by William the Conqueror to build a cathedral suitable ‘to reflect God’s power and authority’ and to be the centre of a diocese of the same name, completed a Norman cathedral shortly before the close of the eleventh century. A fire in 1141 and an earthquake forty years later destroyed most of that church and it was not until the arrival of Bishop Hugh in 1186 that work started on a replacement. It was Hugh who began the building of the present magnificent structure, working from the east end to build in the Gothic style, eventually joining it to what was left of the Norman west front. The latter, with its wonderful frieze of biblical scenes, had been built by his predecessors, Bishops Remigius and Alexander. Even after its completion the cathedral was not without its troubles, the central tower collapsing in 1237, later being rebuilt with a wooden spire that remained in place until blown down in 1548.

The west front of Lincoln Cathedral.

The high altar.

Bishop Hugh was a much revered figure and following his death in 1200 was canonized twenty years later. His name constantly crops up during a tour of the cathedral. Originally the diocese of Lincoln covered an area from the Humber to the Thames and was controlled from Dorchester in the Thames Valley. The centre of the diocese was moved to Lincoln on completion of Hugh’s cathedral, since when its area of authority has been reduced as the population of East Anglia has grown and more dioceses have been created.

The West Window is of Victorian glass and is dominated by a rose window in memory of Bishop Remigius. Entering the nave the visitor is immediately struck by the spaciousness of the cathedral, its lofty pillars and vaulting, with windows of Victorian stained glass on either side depicting scenes from the two testaments. The baptismal font, adjacent to the south-west end of the nave, dates from the twelfth century. It is made of Belgian marble and is carved with a frieze of mythical wild beasts; these symbolize the battle between good and evil with which a Christian must come to terms before being baptised. Baptism has always been perceived as the start of an individual’s journey through Christian life. A font is normally positioned near the principal entrance to a church and invariably, but not always, towards the west end of the building.

The Great East Window.

Considerable damage was inflicted upon the nave of Lincoln Cathedral during the Civil War when Cromwell’s troops were billeted inside the building; windows were damaged and the figures on the Norman west end allegedly used for target practice by ill-disciplined soldiers. For similar reasons there is little or no brass in the building, much of it having been looted. Exceptions are the lectern and chandeliers in the quire.

The transepts are of a similar height to the nave and much of the glass is medieval, being either thirteenth- or fourteenth-century. The south transept is dominated by a circular rose or ‘wheel’ window called the Bishop’s Eye. It looks south to welcome pilgrims journeying to worship at the cathedral on the hill. In the north transept is a corresponding window known as the Dean’s Eye, built later, ‘to ward off evil from the north’. The quire screen below the central tower is carved with a variety of leering and grinning human heads as well as flowers and many different creatures. In medieval times sermons were often delivered by priests standing on top of the screen and addressing those assembled in the nave below. In an aisle leading north out of the main part of the cathedral towards the cloisters is a facsimile of Lincoln’s copy of the Magna Carta; the original has recently been loaned to various exhibitions in America, a country with which the cathedral has links. See also Chapter 5 recording details of Salisbury Cathedral’s copy of the Magna Carta.

The Dean’s Eye in Lincoln Cathedral faces north.

Opposite, the Bishop’s Eye faces south.

The east end and chapter house.

St Hugh’s Quire beyond the screen is where most services are sung. It is the heart of the cathedral, where the dean and canons have their stalls and the bishop his cathedra. Its designation as St Hugh’s Quire further reinforces the age-old debt the cathedral owes him. Further east still is the Angel Quire, so named because of the many angels carved on the stonework; this area of the cathedral was added in 1280 and contains the shrine of St Hugh, to which many miracles have been attributed over the years. A chart explaining the layout of the quire says of St Hugh, ‘He spoke God’s testimonies before kings and were not ashamed’ – a fitting epithet for a great churchman.

The nave looking east.

The Great East Window dominates the eastern end, with its stained glass recounting stories from the Bible, while high up on a north side arch of the Angel Quire is a carving of the Lincoln Imp, a figure whose origins are shrouded in mystery. Was he a real devil who made such a nuisance of himself that the angels turned him to stone? Visitors will need to go to Lincoln to discover, in the process following in the footsteps of the multitude of pilgrims and worshippers who have travelled there for more than nine centuries to visit what must be one of England’s most imposing and best celebrated churches.

Railway Notes

From Lincoln I boarded a second train, which took me via Sleaford and Spalding to Peterborough. Apart from touching the edges of the Lincolnshire Wolds south of Sleaford, the line traverses flat, featureless countryside, much of it criss-crossed by water channels. This heralds a close proximity to the fens and indeed these begin only a few miles to the east. Glasshouses and polytunnels for growing vegetables, field upon field of cabbages and the occasional windmill, all overlaid ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Note

- Preface

- The Journey

- South East

- South West

- Midlands

- North West

- North

- East Anglia

- A Grand Tour

- Cathedral Builders

- Epilogue

- Glossary of Cathedral Terms

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access England's Cathedrals by Train by Murray Naylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.