eBook - ePub

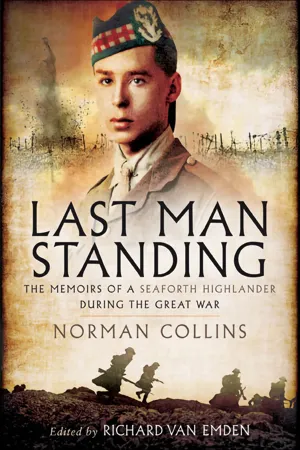

Last Man Standing

The Memiors of a Seaforth Highlander During the Great War

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Last Man Standing

The Memiors of a Seaforth Highlander During the Great War

About this book

A first-hand account of World War I by a nineteen-year-old Englishman who led a platoon into the carnage of the Battle of the Somme.

While researching his excellent earlier book: Veterans of World War I, author Richard Van Emden encountered a fascinating personality of that long-ago conflict. After witnessing German naval attacks on British civilians, Norman Collins enlisted in the Seaforth Highlanders of the 51st Highland Division, even though he was under age. Collins fought at the battles of Beaumont Hamel, Arras, and Passchendaele, and was wounded several times. Collins lived to be 100 and had an unusually detailed collection of letters, documents, illustrations and photographs. Richard Van Emden has written a moving biography of a unique personality at war, and his long life after the dramatic events of his youth.

"This is a harrowing tale of battle, loss and the horrors of war." —Scotland Magazine

"His collection of letters, photographs and the record of interviews as an old man are a treasure trove of information on Western Front fighting." —British Army Review/Soldier Magazine

"Enthralling memoir. These letters form the freshest part of this book, full of detail about kit and food that obsessed soldiers but which do not find a place in the history books." —Who Do You Think You Are?

"This is one of the last great first-person memoirs of the Great War. Extraordinary diary, letter collection and photos." —Scottish Legion News

While researching his excellent earlier book: Veterans of World War I, author Richard Van Emden encountered a fascinating personality of that long-ago conflict. After witnessing German naval attacks on British civilians, Norman Collins enlisted in the Seaforth Highlanders of the 51st Highland Division, even though he was under age. Collins fought at the battles of Beaumont Hamel, Arras, and Passchendaele, and was wounded several times. Collins lived to be 100 and had an unusually detailed collection of letters, documents, illustrations and photographs. Richard Van Emden has written a moving biography of a unique personality at war, and his long life after the dramatic events of his youth.

"This is a harrowing tale of battle, loss and the horrors of war." —Scotland Magazine

"His collection of letters, photographs and the record of interviews as an old man are a treasure trove of information on Western Front fighting." —British Army Review/Soldier Magazine

"Enthralling memoir. These letters form the freshest part of this book, full of detail about kit and food that obsessed soldiers but which do not find a place in the history books." —Who Do You Think You Are?

"This is one of the last great first-person memoirs of the Great War. Extraordinary diary, letter collection and photos." —Scottish Legion News

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Last Man Standing by Norman Collins, Richard van Emden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Enemy at the Gate

On the morning of December 16th 1914 I was sitting having my breakfast porridge. I was seventeen years old and had been working for a year at a local marine engineering company in Hartlepool where I was serving an apprenticeship. I was due to leave for work when, at about 8.10am, a terrific explosion rocked the house. We had two shore batteries sited nearby and during normal firing practice we received prior warning to open our windows to avoid the glass being shattered by the guns’ blast, but this was no normal firing practice, for following the inferno of noise there came a reek of high explosive. I didn’t know what had happened so I rushed outside. Clouds of brick dust and smoke eddied around me before I ran towards the promenade which was only 50 yards away. On the seafront, half left, were three huge grey German battlecruisers, blazing away, and in the dull light of a winter’s morning it was like looking into a furnace. At first I didn’t understand the screeching noise that passed over my head like huge pencils on slate, and then I realised they were shells. The ships were firing at the shore batteries of which we had two, each with small six-inch guns. I was fifty yards from the lighthouse battery on what was known as the Heugh Headland. This battery had three naval guns and I could see that they were hammering away at one ship in particular, although I could not hear them above the blast of the German guns as they belched clouds of flame and smoke.

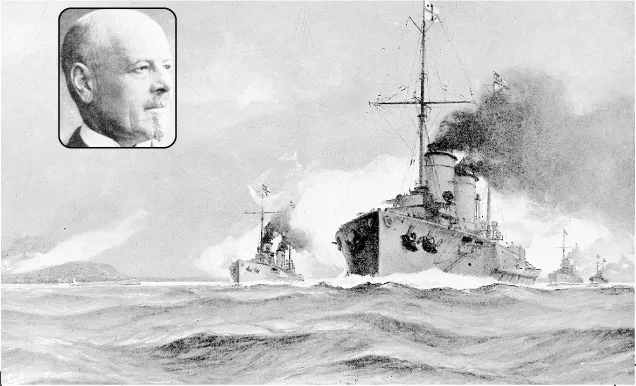

German depiction of her battlecruisers closing in on the English east coast, 16 December 1914. Inset: in command of the force and aboard his flagship HIMS Seydlitz, Admiral Franz von Hipper (1863-1932).

Each ship had about eight large guns, so that there were about 24 large shells being fired on the town at any one time. I stood there watching them, and, you know, it was an amazing sight to watch broadsides from battlecruisers as close as that.

There would be a broadside, then they turned about and fired another broadside, and this went on for at least half an hour. I was standing at the base of the breakwater where it joined the promenade and I wondered if the Germans were going to land, so I turned away and retraced my steps to my home in Rowell Street and turned left towards the Baptist chapel. A great hole appeared in its stone façade as I approached it.

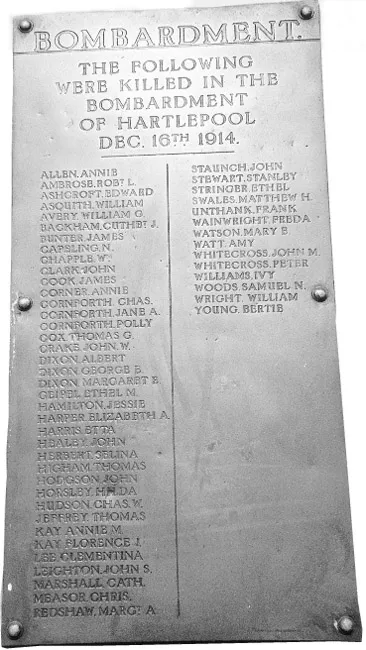

Walking towards town was one of the silliest things I have ever done, as I was walking into a battlefield, walking among the shells that were exploding. Yet I had no feeling of panic whatsoever. Just as I turned the corner into Lumley Street, I saw the body of Sammy Woods, aged nineteen, a school and Sunday School friend of mine; he was lying half in and half out of his doorway, dead of course. He had been caught by a shell that had fallen to my left into the rectory that belonged to St Hilda’s Church. A shell had burst just as he stepped out and a second before I turned the corner.

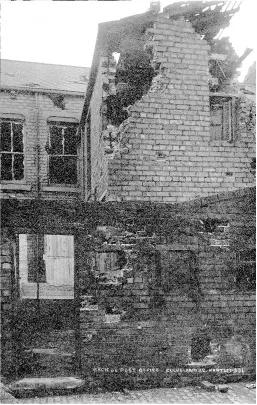

Images of severe damage after the bombardment. Several affected streets have since been demolished.

I continued walking. I looked at St Hilda’s church. Shells were dropping fairly close but I didn’t see any hit, so I kept on going. I walked down towards the docks and I saw the town gasometer receive a hit and of course, with the gas escaping, it went down and collapsed. The shells were dropping too along the dockside, amongst the pit props on the quayside. Now a pit prop is like a tree trunk and was used in the galleries of coalmines, and as this was County Durham we needed thousands of them. As the shells were dropping in amongst them the props were all going up in the air just like boxes of matches, only of course these pit props weighed over a hundredweight each.

I’d never been under fire before and I didn’t quite know how it operated. I was just walking through an incident, like a spectator to an event, a heavier bombardment than was probably taking place on the Western Front at that time. I can’t remember being frightened. I wouldn’t have been human if I wasn’t but the whole thing was too much of a shock really, so out of the ordinary, and that suppresses fear.

Having exhausted the view, I walked on into the town, past a wall and under the railway bridge, round to the other side of the docks to where Sir William Grey and Company had their marine works. I wondered what was going on there because nobody had turned up for duty or, if they had, they’d gone. I was looking at the docks from the opposite side but there was nothing new, so I decided then I’d better go back and see what had happened to my parents. I don’t know why I hadn’t thought of that before. As I made my way back I saw plenty of women running around, screaming, with babies in their arms, trying to get rid of them, to give them to somebody who could help, but there was nobody. I saw two women rush up to a soldier who was obviously trying to make his way to the Garrison, and try and push a baby into his arms. Of course he couldn’t do it, he was on duty in any case, so he refused. Then one of the woman came to me, but I also refused. Other people were carrying their most precious possessions. One realist had a mattress on his head as he staggered up Hart Lane.

Top, the rectory, bottom 7 Victoria Place where forty-nine year old William Avery, an adjutant in the Salvation Army, was killed. The insets show the houses as they appear today.

The noise of the shells began to lessen about 8.50 and finally only the occasional explosion occurred and then silence. A proclamation was made by the mayor and delivered through the town crier. He appeared and started shouting for everyone to keep calm, letting people know that the shelling had stopped and that there was no immediate danger, and no landing had taken place. He informed us that the situation was now secure, whatever that meant! I got back to the promenade and asked someone if they had seen my father. They replied that he had last been seen pushing a wheelchair towards the open country with an invalid in it.

Back home, I found mother in the kitchen making cups of tea for anyone who wanted one. I thought, ‘Well, that’s just like mother’. I went in and there she was, as calm as could be, so I began calling on relatives near at hand, and apart from a connection by marriage who had lost a limb in Victoria Place, we had suffered no serious injuries. Later that morning I went and collected pieces of shell. There was debris everywhere. Shell fragments, some weighing several pounds, were being collected as souvenirs and I still have several which came through the roof of our house. They bristle with jagged edges and the mortar is still lodged in the steel. Elsewhere I found a dead donkey that had been grazing in the friarage field, the home ground of the Hartlepool Rovers Rugby Football Club, and I have the piece of shell that killed it.

A collection of German shells that failed to explode.

There was some panic, but not a great deal, as I remember. A lot of people had been killed and wounded and people were being removed from buildings which had been damaged, and taken to hospital. (9 soldiers were killed, 37 children and 97 men and women. 466 were wounded.) I understand that around 1500 shells were fired but they didn’t do the damage they were designed to do. A twelve-inch armour piercing shell was intended to be fired against the sides of a battleship that has perhaps twelve inches of armour plating. But in Hartlepool there was nothing to stop the shells going straight through a house, and many failed to explode.

It wasn’t all one way. The shore battery I had seen pounding away had scored a direct hit on a gun crew of the Blücucher. I later found out that the other ships in the raid had been Germany’s very latest, the Moltke and the Seydlitz.

The bombardment of Hartlepool was hushed up to a certain extent because the press said it was an undefended town. This wasn’t true as Hartlepool put up a good defence with what it had, indeed the first soldier to be killed on British soil in the Great War died with the Heugh Battery and there is a plaque commemorating the event to this day. The Germans had every right to bombard Hartlepool. Whitby and Scarborough on the other hand were undefended. Although only a few dozen shells were fired into these towns, they took the full publicity for this very reason. Later, when I joined the army at Dingwall, I took some of the photographs of the bombardment taken by a local man, and most of the recruits had never heard of the attack.

A fragment of shell casing picked up by Norman. This piece killed a donkey in the field next to the Friary.

A plaque commemorating those who were killed. The name of Norman’s friend Sammy Woods, who was killed as he left his house, can be seen.

CHAPTER TWO

An Edwardian Childhood

I was the second son of Frederick and Margaret Collins and was christened William Norman, although all my life I preferred my second name. My parents and grandparents were good Methodists, clean living, teetotal, and well read. My father, Frederick Collins, worked at the same engineering firm to which I was later to be apprenticed, but his r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements and Picture Credits

- Introduction

- Chapter One The – Enemy at the Gate

- Chapter Two – An Edwardian Childhood

- Chapter Three – A Shilling a Day

- Chapter Four – The King’s Commission

- Chapter Five – Over the Pond

- Chapter Six – Hell! Here Comes a Whizz-Bang

- Chapter Seven – Back in the Frying Pan

- Chapter Eight – Rest and Recuperation

- Chapter Nine – The Armistice and the Aftermath

- Postscript