- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

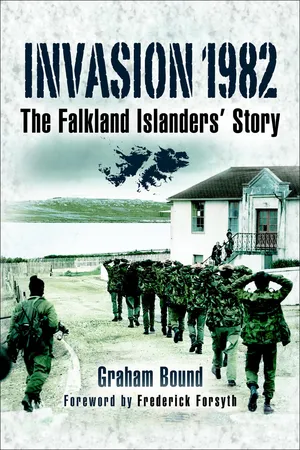

The story of British Falkland Islanders under Argentine occupation—with a new chapter on postwar developments: "Reads like a gripping adventure yarn." —

British Heritage Magazine

Falkland Islanders were the first British people to come under enemy occupation since the Channel Islanders during the Second World War. This book tells how islanders' warnings were ignored in London, how their slim defenses gave way to a massive invasion, and how they survived occupation.

While some among the small population established a cautiously pragmatic modus vivendi with the occupiers, some islanders opted for active resistance. Others joined advancing British troops, transporting ammunition and leading men to the battlefields. Islanders' leaders and "troublemakers" faced internal exile, and whole settlements were imprisoned, becoming virtual hostages. A new chapter about Falklands history since 1982 reveals that while the Falklands have benefited greatly from Britain's ongoing commitment to them, a cold war continues in the south Atlantic. To the annoyance of the Argentines, the islands have prospered—and an oil bonanza promises further riches.

Includes a foreword by Frederick Forsyth

Falkland Islanders were the first British people to come under enemy occupation since the Channel Islanders during the Second World War. This book tells how islanders' warnings were ignored in London, how their slim defenses gave way to a massive invasion, and how they survived occupation.

While some among the small population established a cautiously pragmatic modus vivendi with the occupiers, some islanders opted for active resistance. Others joined advancing British troops, transporting ammunition and leading men to the battlefields. Islanders' leaders and "troublemakers" faced internal exile, and whole settlements were imprisoned, becoming virtual hostages. A new chapter about Falklands history since 1982 reveals that while the Falklands have benefited greatly from Britain's ongoing commitment to them, a cold war continues in the south Atlantic. To the annoyance of the Argentines, the islands have prospered—and an oil bonanza promises further riches.

Includes a foreword by Frederick Forsyth

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Invasion 1982 by Graham Bound in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The 150-Year Echo

At five minutes past six on the morning of 2 April 1982 several loud explosions ripped through the Royal Marines barracks at the west end of Stanley Harbour.

It was a calm pre-dawn morning and the noise of the grenades and rockets launched by the Argentine special forces as they attacked Moody Brook rolled across the still harbour, echoing off the ridge on the north shore, disturbing logger ducks and kelp geese along the beach, and rattling windows in the cottages of Stanley.

At the headquarters of the Falkland Islands Defence Force (FIDF), a rambling weatherboard and corrugated iron building in the centre of Stanley, Major Phil Summers, Assistant Government Chief Secretary by day and commander of the forty-strong civilian militia on weekends, heard the explosions.

The senior officer had been at the HQ since about 7.30 the night before, having dutifully turned out in response to the news that an Argentine invasion was imminent. After a short briefing by Governor Rex Hunt, Phil Summers and his officers had allocated key positions for the men to guard and issued weapons and ammunition.

Major Summers could have been a figure from Dad’s Army – there were shades of Captain Mainwaring. Indeed the Defence Force was affectionately known as that. Rotund and not cutting a fine figure in uniform, he was more at home in his daytime environment, the Government Secretariat. But, like the other ill-prepared men who turned out that night, he was no coward and he accepted without question that he was to do his duty.

As the explosions faded, the CO found a dignity that sometimes eluded him and strode out of the drill hall onto John Street. In a steady and firm voice, calculated to instil a little more confidence in the unfortunates who defended the road with ancient Lee Enfield bolt-action rifles, he said, “Right lads, it’s started.”

In his voice was resignation, and perhaps even a hint of relief. Like other Falkland Islanders, he had been waiting years for ‘it’; the final day of reckoning in the long-simmering dispute with Argentina. They had never discussed invasion; it was a taboo word. Like cancer, there was not a lot that could be done to avoid it and not much point in talking about it. If ‘it’ happened, it had to be faced bravely.

The sounds of aggression had, in a sense, echoed not just across Stanley’s still harbour, but across the decades.

Argentines insist that 2 April was simply the latest act in a drama that had begun 149 years earlier in 1833. Then, they allege, British forces sacked the settlement at Puerto Soledad which the infant country had inherited from the Spanish, and deported the colonists.

That the British had never abandoned their earlier claim to the Islands, and the Argentine inheritance of all Spanish claims in the area is at the very least of debatable legality, matters not at all. The loss of the Malvinas was a slap in the face of the nation, never to be forgotten.

But the Malvinas only emerged as an Argentine cause célèbre in 1946, soon after the charismatic caudillo Juan Domingo Peron had placed the sky-blue sash of the presidency across his chest. Searching for an issue which would unite all Argentines, he set his diplomats to work rejuvenating the Malvinas dispute.

From then on Argentina harried the British Government. In 1964 they succeeded in placing the issue on the agenda of the United Nations. Britain protested, but the following year the UN General Assembly formally urged the two countries to discuss their dispute.

In the Falklands, where the main concerns of life had nothing to do with such arcane history, the Argentine claim was ignored. There was a vague awareness that the neighbours were best avoided, but who needed them anyway? Trading links were happily and firmly established with Montevideo in Uruguay.

Monthly steamers travelled the 1,000 miles to and from Montevideo, carrying exported wool, sick Islanders for treatment at the British Hospital, children for education at the British School, and holidaying colonial administrators who caught the Royal Mail ships on from the River Plate to Southampton.

In 1966 things changed. A bizarre event brought the dispute and the threat home. On 26 September, a clear early spring day, the rumble of multiple aero-engines disturbed the peace of tiny sheep farming settlements on the west of the Islands. Reports of the strange sound reached Stanley shortly before a large four-engined Douglas DC4 aircraft, bearing the colours of Aerolineas Argentinas, appeared over the town. It circled, losing height and apparently searching for an airport. People poured onto the streets for a better view.

The airliner, by far the largest aircraft ever seen over the Falklands, was carrying about forty passengers, fresh produce and crates of newly hatched chicks. It had taken off several hours earlier from the northern Patagonian town of Bahia Blanca for a flight to Rio Gallegos in the far south. Soon after take-off a number of the passengers emerged from their seats, reached into their hand luggage and produced guns.

The hijackers, including a vivacious young blonde woman (Islanders were later shocked by the rumour that a generous stock of condoms had been found along with the ammunition in her bag), were the extreme right-wing Condor Group. They ordered the captain to change course for the Malvinas, where they intended to reclaim the Islands for the motherland.

The crew must have had concerns, but the Argentine guerrillas appeared blissfully unaware that Stanley had no airport. In those days the only aircraft to operate within the Falklands were the De Havilland Beaver floatplanes of the Government Air Service, a bush-style operation that linked the farm settlements and tiny island communities.

But the DC4 needed to put down somewhere and Islanders felt a mixture of alarm and relief when it began to descend in the direction of the racecourse. Landing such a large aircraft on a soft stretch of grass with fences and grandstands on each side was desperately dangerous – better, though, than running out of fuel in mid-air. Showing remarkable skill, the pilots touched down lightly and managed to reduce the DC4’s speed before the undercarriage began ploughing into the soft turf. Eventually it came to a jarring stop, still upright but with its wheels well and truly stuck. Remarkably, there were no injuries.

Falkland Islanders have rarely been criticised for their lack of hospitality and on this day they excelled. Clearly the passengers and crew were in trouble and many locals leapt into their Land Rovers and sped to the racecourse, intent on doing whatever they could to help. To their horror, guerrillas waving guns met them. Many well-intending locals, including Police Officer Terry Peck (who would later make his name in the 1982 war) were herded aboard the aircraft to join the innocent passengers and crew as hostages. Outside the plane, the Argentines raised an Argentine flag and began distributing leaflets stating their purpose.

It was a dangerous situation with elements of farce. The Governor and his second in command, the Colonial Secretary – both London appointees – were in Britain, and the senior civil servants were two local men, Financial Secretary Les Gleadell and Assistant Colonial Secretary HL ‘Nap’ Bound. This was one of the first cases of terrorists hijacking an airliner; it may have been the first. Whether it was or not, the crime had not yet taken on the sinister significance that is attached to it today, and the two men struggled to find a phrase to describe the incident. Eventually they cabled the Foreign Office in London to say that there had been a case of ‘air piracy’. In a reply that was strangely similar to the unhelpful advice given to Governor Rex Hunt on the eve of the 1982 invasion, the two senior locals were told to manage as best they could.

Stanley’s meagre military force was mobilised to support the handful of unarmed policemen. It was a moment of glory for the Defence Force. Only six Royal Marines were then based in Stanley, training the local men and advising the Governor on issues of security and defence. They suggested the Defence Force stake out the DC4, denying the ‘pirates’ water, warmth and sleep.

This may have been the only terrorist incident that ended thanks to Jimmy Shand, Russ Conway and the Beatles. The Force set up loudspeakers around the plane and a DJ maintained a constant flow of furious Scottish jigs and rinky-tink piano tunes. This was a low trick and the Argentines could not hold out for long.

Hostage Terry Peck waited until his captors’ attention was diverted and secreted himself beneath the ample robes of the local Anglican priest, who had gained access to the aircraft and was attempting to negotiate. The policeman was a small, wiry young man, but the priest was still left looking little short of pregnant. Moving in awkward unison the two crossed the FIDF lines successfully.

As light faded, the temperature dropped, the plane’s toilets backed up, water became short and the DJ introduced his pièce de résistance – his collection of Beatles’ singles. The next morning the guerillas asked the priest to convey their surrender to the authorities.

In the same self-serving and appeasing fashion that characterised policy in the months before the 1982 invasion, London decided that Argentina was not to be provoked with a stiff response. There would be no local trial and the hijackers were held in an annexe to the Catholic church rather than in prison. A few days later an Argentine steamer, the Bahia Buen Suceso, dropped anchor in Port William, Stanley’s outer harbour, and embarked the hijackers.

Back home, the Condor group were heroes and the authorities charged them only with relatively minor offences. Some of the group received suspended sentences and even the vivacious blonde deputy leader was free within a few years.

The Islanders had handled the first Argentine assault on the Islands well and with very little help from London. Indeed, in the aftermath of the incident, they had been let down by the British Government.

It had been no invasion, but the incident had brought the Argentine threat into the open. Soon afterwards, the town’s fire alarms were altered to give an optional wavering tone, which would be the invasion alarm. Large timber obstructions were placed on the racecourse to stop any future landing.

Slowly but inexorably the threat increased, not only from the near neighbour, but – in a political sense – from London as well. Later in 1966 it became clear that British diplomats were manoeuvring to solve the problem of a colony which was of no further use to Britain. If necessary, they would do this by conceding to Argentine demands.

There was the small matter of the Islanders to consider, but handling them should not be beyond the wit of Whitehall. 2,000 sheep farmers would be encouraged to be reasonable and accept that reliance on Britain 8,000 miles away no longer made sense. A warmer relationship with Argentina, on the other hand, really was rather a good idea.

In 1968 Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart shocked Parliament and the Islanders by admitting that he had initiated talks about sovereignty during a visit to Buenos Aires the previous year. He said Britain was confident about the justice of its claim, but so was Argentina, and both sides had to address this if there was to be any dialogue at all.

It was the beginning of a Machiavellian diplomatic process, continued dogmatically by whatever government was in power until the outbreak of war in 1982.

Missions to the Falklands by junior foreign office ministers became relatively routine. They would arrive with, at best, a message of watery support and appeals for realism, at worst with details of a new and unsavoury political reality or proposal. It was easy for the ministers and their men to convey their messages without the inconvenience of debate or criticism, because local government was dominated by the Governor and other officials nominated by London. Executive Council meetings, upon which few democratically elected members sat, were conducted in secret. Independent news media did not exist. The local radio station was owned and controlled by the government, and (in the early days, at least) the only newspaper was the Monthly Review, a duplicated paper of dry record that occasionally carried government statements without comment, and was otherwise notable for its “hatched, matched and despatched” column.

But ministers and officials underestimated the Islanders. Knowing that they could not successfully fight the Foreign Office alone, a group of leading Islanders mobilised influential friends in Britain, including back-bench Members of Parliament, into a remarkably effective pressure and lobby group.

The Argentines hated the Emergency Committee, as it was known, sneering that it was actually the instrument of the Falkland Islands Company who simply want to continue plundering the Islands’ economy. But the committee became a permanent thorn in the side of the Foreign Office. It countered every official move with public reminders that the Islanders were loyal subjects of the Queen who had settled in a none-too comfortable colony when the crown valued its empire, and who did their bit in support of the mother country during two world wars. Their ‘wishes’, not just their ‘interests,’ had to be respected.

Assessments of the military threat at that time are not known, but in 1968 London beefed up the Royal Marines detachment, calling it Naval Party 8901 and basing it in the long abandoned and virtually derelict wireless transmitting station at Moody Brook. It is slightly puzzling that London bothered to increase the garrison at all, but it is possible that a force of less than platoon size would find it difficult to sustain itself economically and with any degree of independence. In any case, as a signal to the Argentines, the lightly armed force of about thirty men did not seem to be saying much. It was easy to assume that because Britain had committed such a meagre force it cared little about the Islands.

London still hoped that the Islanders would come to depend on their big neighbour. In 1971, following more secret talks, the pressure was ratcheted up. Falkland Islanders were told that their subsidised shipping link with Uruguay could not continue. They were presented with a new arrangement, one that pushed them firmly into bed with Buenos Aires. No one in the Islands liked it, but there was no choice.

The Communications Agreement was dressed up as a joint commitment to support the Islands. The Argentines would build a temporary airstrip so that its state airline, Lineas Aereas del Estado (LADE), could operate a weekly service to and from the mainland. For its part, Britain would build a permanent airport, and (to counter the argument that too much reliance was being placed on Argentina) also provide a passenger-cargo ship operating to South America. It was implied that the new ship would be capable of trading with Uruguay if the Argentines ever abused their monopoly over air services.

This fooled no one. The small print was alarming: to travel through Argentina locals would need a ‘tarjeta provisorio,’ a provisional card, bearing their personal details and the Argentine coat of arms. Issued in Buenos Aires, the much-hated ‘white card,’ as locals knew it, was a de facto Argentine passport. The Argentines would also set up an office in Stanley to run LADE and even mail would be routed through Argentina, where it would be rubber-stamped twice with lavish English and Spanish cachets. The agreement allowed the Argentines to continue viewing Islanders as Argentine citizens, but with patronising generosity Buenos Aires said it would not insist that Falklands men endure military service. This only suggested that they were really a special kind of Argentine citizen.

With the new dawn in relations came agreements that medical treatment unavailable in Stanley would be provided in Argentina and scholarships would be available for local children to study in Buenos Aires, Cordoba and other Argentine cities.

A little later YPF, the Argentine state oil company, was given a monopoly to provide petrol and diesel in the Islands, while Gas del Estado, another state company, began an attempt to wean Islanders off their free supply of peat.

Some observers have characterised the British policy towards the Falklands before 1982 as one of ‘benign neglect’. This is too generous. By the early 1970s British policy was thoroughly malignant. Chief Secretary at the time was Tom Laing. His brief was to do all he could to foster relations between the Islands and the Argentines. “Do what you can to get people together,” his Whitehall bosses told him.

The master plan was not subtle. Given a decade or two, Falklanders would accept the Argentines; indeed those who had been educated there would virtually be Argentines. Problem solved.

Not surprisingly, deep political anger was directed at the British Government – particularly the deceitful Foreign Office, which had conceived and carried out the strategy. Local rage increased when the Foreign Office reneged on its side of the Communciations Agreement. Although Britain did eventually fund the building of a small permanent airstrip at Stanley (notably too small to allow flights from Britain), the shipping link, which would have weakened the Argentine grip, never materialised. This was, quite simply, a broken promise.

Periodically over the next decade, Islanders requested – indeed almost demanded – the extension of territorial waters beyond the negligible few miles. This would have enabled Stanley to issue licences to the fishing fleets that were scooping up hugely valuable catches within sight of the Islands. The resulting revenue would almost certainly reverse the declining economy, and the move was within London’s power, as was shown in the aftermath of the 1982 war, when a zone covering thousands of square miles of valuable ocean was declared posthaste. But, of course, no one in Whitehall wanted the Islanders to prosper.

Notwithstanding the skulduggery and the anger, the decade between 1971 and 1981 was not entirely unhappy in Stanley. Emigration to better lives in Britain and New Zealand continued, but (on a human level at least) many of those who stayed got along reasonably well with the Argentines who were posted to Stanley to maintain the air and fuel services. Politics was politel...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Chapter One - The 150-Year Echo

- Chapter Two - Warning Signals

- Chapter Three - Battle for Stanley

- Chapter Four - Waking up to Reality

- Chapter Five - Good Argie, Bad Argie

- Chapter Six - Surviving the Siege

- Chapter Seven - Radio Resistance

- Chapter Eight - Goose Green

- Chapter Nine - Local Hero

- Chapter Ten - The Fighting Farmers

- Chapter Eleven - “In two hours you will be free”

- Chapter Twelve - The Next Falklands War