- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

British Naval Swords and Swordmanship

About this book

This new publication is intended to bring together a mass of research dealing with all aspects of British naval swords. Unlike the much sought after Swords of Sea Service by May and Annis, this work offers a far broader coverage and, for the first time, the complete story of swords and swordsmanship is presented in one concise volume. While the swords themselves are described the authors also tell the story of naval swordsmanship For exsample, subjects such as how swords and cutlasses were used in action and how training was conducted and covered. The authors also address how how the use of swords developed into a sport in the Navy, and how swords and swordsmanship may have entered naval symbology in such areas as ships' names. Many current myths are addressed and corrected, and the story is brought right up to date with information on the sport from 1948 to 2000. While the book concentrates on the Royal Navy, foreign weapons, including those of the Irish Naval Service, are mentioned where appropriate Other British Maritime organisations such as the Merchant Navy, the Customs and Coastguard Services, and the Reserves are also addressed The book also covers subjects such as dating, collecting, and conservation of swords and re-examines those swords attributed to Nelson. The Appendices include the first list of Swords of Peace awarded to naval units to be published. Recent research by the authors is also reflected in the updated lists of Patriotic Fund Awards, City of London Swords, and Naval fencing champions contained in the Appendicitises The comprehensive nature of the work has not been attempted before and the book will appeal to a wide range of naval enthusiasts and historians, collectors of weapons, fencers and re-enactors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access British Naval Swords and Swordmanship by Mark Barton,John McGrath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Naval Sword in Action

Sailors fought at sea with swords and other edged weapons for millennia, but misconceptions abound about how these weapons were employed by mariners, particularly from around 1650 until the beginning of the twentieth century. In this chapter, we discuss how sailors used swords and edged weapons in battle, both on shore and at sea, and in duelling. We also tackle the question of when swords were last used in action, and look at how they are used by today’s naval officers.

The traditional image of sailors hacking their way aboard enemy vessels is far from the whole story; the majority of naval engagements throughout this period involved battles with cannon or were cutting-out expeditions, in which sailors would enter a harbour and capture or destroy enemy vessels or strongholds.

Five edged weapons were deployed at sea: the sword, the cutlass, the pike, the axe and the bayonet. Swords were personal weapons, owned by officers. Cutlasses and pikes were supplied to the ship’s company as part of the ship’s equipment. Axes were intended to be used to deal with damaged rigging such as ropes and spars, but were often used as weapons. Bayonets arrived attached to the muskets of the Marines in the seventeenth century and were later issued to the naval brigades in the nineteenth century. Sailors would also use whatever came to hand in the heat of hand-to-hand fighting, such as dirks, knives and marlinspikes. Most of what is described in this chapter applies not only to swords but also to these other weapons.

One of the main uses of swords was as part of boarding operations at the end of a gunnery battle. As one ship’s fire slackened, the stronger vessel would come alongside and seek to board her if she had not already struck her colours. As Nelson phrased it: ‘No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy.’ Unlike in earlier periods, when hand-to-hand fighting between vessels constituted the main naval tactic, from the seventeenth century, ships aimed to blast their opponents into submission using cannon fire. However, since the ships’ hulls were typically 2ft thick1 and built to resist roundshot, we should not be surprised that it was necessary to manoeuvre to close quarters. From the concept of the line of battle developed by Admiral Blake in 1653,2 tactics for sea battles evolved with the aim being to reduce the enemy through a broadside duel.3 However, this would often fail to force the enemy to strike his colours. In these circumstances, a captain would have to lay his vessel alongside and prepare to board and to repel boarders from the enemy ship. Since this would be almost certainly after an engagement with the great guns, it would be a desperate struggle and, as one might expect, techniques were brutal and relied on the sailors’ stamina and strength.

The scale and ferocity of naval warfare meant that sword drill had to be simple so that men could fight instinctively. A First Rate ship of the line would mount a hundred or more guns and fire a broadside of some 2000lbs4 of shot. At the battle of Waterloo, by comparison, British land forces had thirty-nine guns, able to fire around 276lbs of shot.5 Furthermore, gun engagements at sea would last for many hours. At the battle of Barfleur in 1692, vessels engaged in broadside duels for eleven hours. Even the battle of Trafalgar involved 4 1/2 hours of broadsides and action. Unsurprisingly, sailors were issued with an extra ration of spirits prior to a battle, to anaesthetise them to the noise and the shock of constant bombardment and give them Dutch courage.

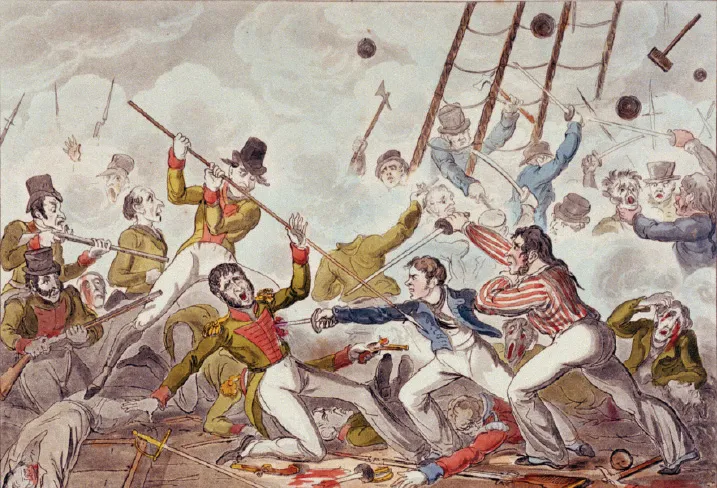

One of a series of coloured aquatints by George Cruikshank following the character Mr B, in this case with ‘Mr B seeking the bubble reputation’. (Published by Thomas Maclean, 1 August 1835. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAD4725)

Long battles are exhausting. Michael Loades, the historical weapons expert, comments: ‘Even the fittest of men will tire after several minutes of hard fighting. Delivering blows that are capable of severing limbs requires huge reserves of energy. 6 A fighting sword of the period would typically weigh nearly 3lbs (1.36kg), a pound more than a modern ceremonial sword. The power of such blows should not be underestimated. During an attack on a fort in Muros Bay in Northern Spain, Lieutenant Yeo felled the fort’s governor with a single stroke of the blade, but in doing so broke his own sword in two.7 Since the age of chariots, warriors fighting on land had found ways to gain respite in the midst of battle. As Julius Caesar wrote in his Gallic Wars:

[They] leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The charioteers in the meantime withdraw a little distance from the battle, and so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops.8

However, in the close confines and crowded decks of a man of war there would be little opportunity to take a break until victory, surrender or the ships drifted apart. This is perhaps why the early cutlass drills involved exercising with both arms.

Boarding Actions

Three main types of action involved sword fighting – boarding, cutting out and landings. In 1813, the 350-strong crew of the 38-gun HMS Shannon boarded the USS Chesapeake. The men of the Shannon were armed with around 75 boarding axes, 100 boarding pikes, 150 cutlasses, 100 muskets and around 100 pistols with steel belt hooks. Each man in a gun crew had at least one secondary role, and half the gun crews were designated as boarders, three designated as first boarders and three more as second boarders.The first boarders were the assault party, and each would be issued with a cutlass and pistol. The second boarders were primarily the defensive force and would have pikes and axes.9 Like modern sailors, the men prepared for close-quarters combat by tidying away loose ends of their dress – they would tie handkerchiefs around their heads and ensure their shirtsleeves were tucked up.10

This scale seems to be typical: when fitting out in 1805 for a crew of eighty-five men, the British whaler Port-au-Prince, which only intended to indulge in opportunistic privateering, was equipped with fifty small arms, fifty cutlasses, twenty barrels of gunpowder, twenty great roundshot and 50 hundredweight of small shot. The ship was 466 tons with twenty-eight guns (6, 9 and 12pdrs).11

Boarding was usually conducted when the enemy was on the defensive, having suffered a mauling by broadside.12 However, this was not always the case. The usual tactic was reversed to good effect by Lord Cochrane and HMS Speedy in 1801 in a fight with the much larger Spanish frigate El Gamo. Whenever the Spanish were about to board, Cochrane would endeavour to pull away and fire on the gathered boarding parties. He eventually boarded the El Gamo himself, despite still being heavily outnumbered.13

A boarding would be a brutal and crowded affair. There was unlikely to be the room on a deck in the struggle that would give space for the elegant one-on-one combat loved by Hollywood. However, even contemporary accounts give rise to the man on man image, one French newspaper reporting14 after the battle of Trafalgar how, apparently, Admiral Villeneuve offered Nelson a pistol so that they could fight fairly. The same report also declared it a complete French victory, and was sure their vessels had only been scattered by the subsequent storm.

Nelson boarding a Spanish launch in July 1797. (Oil painting by Richard Westall, 1806. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, BHC2908)

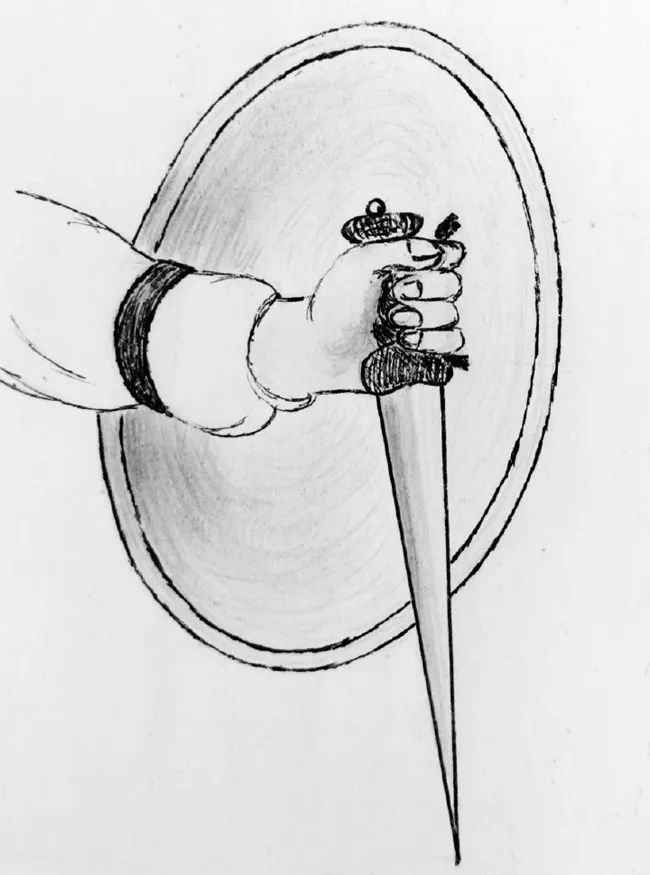

Captain Selwyn RN commented at a Royal United Services Institute Lecture in 1862, that in the press of battle a sailor ‘having got up his sword arm and being unable to get it down again, [had] to use the hilt of his cutlass, and knock his enemy’s teeth down his throat’.15 Captain Selwyn then commented on the habit of Lord Cochrane of arming his sailors for boarding with bayonets fastened to the outsides of their left arms with the points projecting 6in beyond the hand and then arming them only with cutlasses, telling them to attack. The bayonet formed a guard for defence as well as enabling attack. The responding lecturer, Mr John Latham, who ran Wilkinson’s Swords at the time, commented this is effective and matched the Scottish method of fighting with a sword, dirk and targe; the targe being a small shield usually less than 20in in diameter. The dirk would be held in the same hand as the targe to help with defence (Lord Cochrane was, of course, a Scottish officer).

The preponderance of rigging and other obstructions added to the difficulty of fighting with swords during boarding. It should not be surprising that one notable difference between military and naval sword drills is the lack of over-the-head strokes in the latter, although there is a head defence. That this was probably common among most navies could be indicated by the fact that only the US Navy issued helmets to its personnel during the Napoleonic war. Although the defence was sometimes needed, as Captain Chamier comments, ‘... he made a desperate cut at me. My head, thick as it is, was defended by my cutlass’.16

Holding a dagger behind a targe.

Sir Edward Howard standing on the gunwale prior to being forced over the side. (Navy and Army Illustrated, 19 November 1897, p 60)

It was important in any boarding action for the vessels to remain alongside, to enable reinforcement and facilitate retreat. When they did not, things could go very badly, as illustrated by the action at Conquet Bay on 25 April 1513. A squadron of French galleys had come round from the Mediterranean, under the command of the Chevalier Prégent de Bidoux, and had anchored in Whitsand Bay. An English council of war determined that they might be attacked. It was found that the galleys were drawn up close to the shore, in very shoal water, so the British admiral, Sir Edward Howard, resolved to cut them out with his boats and some small row-barges attached to the fleet. Howard ran his boats alongside the French and then leapt sword in hand along with seventeen crew on board the French vessel. The vessels separated again and, now trapped and unsupported, the British were forced back by pikes and sheer weight of numbers, and slowly pushed overboard. Sir Edward being the last, eventually ended on the gunwale. He threw his gold nobles and whistle that were his marks of office into the sea to prevent them falling into the hands of the French before he, too, was forced overboard and drowned.17 Howard’s death was felt as a national disaster. In a letter to Henry VIII, James IV of Scotland wrote: ‘Surely, dearest brother, we think more loss is to you of your late admiral, who deceased to his great honour and laud, than the advantage might have been of the winning of all the French galleys and their equipage.’18

British naval superiority in the Napoleonic period and Nelson’s exploits in battles such as the battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797, when he captured the San Nicolas and then used her to capture the San Josef (a feat subsequently referred to as ‘Nelson’s patent bridge for boarding First Rates’), mean we often think of boarding as a British activity. But it is sometimes forgotten that boarding was a favoured French tactic.19 The French government focussed on land campaigns and, fo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Naval Sword in Action

- 2 Cutlasses

- 3 Officers’ Swords

- 4 Dirks

- 5 Swords of Officers of the Reserves, the Merchant Navy and Other Maritime Organisations

- 6 Presentation Swords

- 7 Nelson’s Swords

- 8 Training in Swordsmanship

- 9 Transition to a Sport

- 10 Your Naval Sword

- Appendix 1: Patriotic Fund of Lloyds – Swords Awarded

- Appendix 2: City of London Presentation Swords

- Appendix 3: Naval Service Awards of the Wilkinson Swords of Peace

- Appendix 4: Service Champions and Trophies

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Notes