- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A fascinating examination of why England failed for so long to colonize North America, in contrast to Spain's rapid conquest farther south.

Within a generation of Columbus's first landfall in the Caribbean, Spain ruled an empire in central and south America many times the size of the home country. In stark contrast, after a century of struggle, and numerous disasters, English colonizing efforts farther north had succeeded in settling the banks of one waterway and the littoral of several bays. How and why progress was so slow and laborious is the central theme of this thought-provoking new book.

Invading America argues that this is best understood if the development of the English colonies is seen as a protracted amphibious operation, governed by all the factors that traditionally make for success or failure in such endeavors—aspects such as proper reconnaissance, establishing a secure bridgehead, and timely reinforcement. It examines the vessels and the voyages, the unrealistic ambitions of their promoters, the nature of the conflict with the native Indians, and the lack of leadership and cooperation that was so essential for success.

Using documentary evidence and vivid firsthand accounts, it describes from a new perspective the often tragic, sometimes heroic, attempts to settle on the American coast and suggests why these so often ended in failure. As this book shows, the emergence of a powerful United States was neither inevitable nor easily achieved.

Includes illustrations and a list of historic sites

Within a generation of Columbus's first landfall in the Caribbean, Spain ruled an empire in central and south America many times the size of the home country. In stark contrast, after a century of struggle, and numerous disasters, English colonizing efforts farther north had succeeded in settling the banks of one waterway and the littoral of several bays. How and why progress was so slow and laborious is the central theme of this thought-provoking new book.

Invading America argues that this is best understood if the development of the English colonies is seen as a protracted amphibious operation, governed by all the factors that traditionally make for success or failure in such endeavors—aspects such as proper reconnaissance, establishing a secure bridgehead, and timely reinforcement. It examines the vessels and the voyages, the unrealistic ambitions of their promoters, the nature of the conflict with the native Indians, and the lack of leadership and cooperation that was so essential for success.

Using documentary evidence and vivid firsthand accounts, it describes from a new perspective the often tragic, sometimes heroic, attempts to settle on the American coast and suggests why these so often ended in failure. As this book shows, the emergence of a powerful United States was neither inevitable nor easily achieved.

Includes illustrations and a list of historic sites

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Invading America by David Childs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Five-Finger Exercise

Be it known and made manifest that we have given … to our well-beloved servant John Cabot … licence … to conquer, occupy, possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them thus discovered … acquiring for us the dominion, title, and jurisdiction of the same …

Letter Patent granted to John Cabot by Henry VII, 5 March 1496

In an invasion that occupied much of the sixteenth and the early part of the seventeenth century the English thrust five widespread, thin, stubby and acquisitive fingers into the lengthy flank of the North American continent, where they were bitten off, chewed up or spat out, until at last their persistence allowed them to grasp their prize which was, from Baffin Island in the north to the Carolina Outer Banks in the south, the possession of lands, the rights to which they had been granted by a sovereign who did not own them.

This largesse in grants of land was a feature of the royal charters, whether they were issued to individuals or to companies. Thus, in 1584, Walter Ralegh (the spelling of his name was amended by later generations to Raleigh, a version which was never used by the man nor his peers) was given overlordship of an area extending to six hundred miles either side of his first settlement, which he sycophantically and sensibly named Virginia in honour of the holy state of Elizabeth his Queen, whose favourite he was. Her successor, James I, in the first Virginia Company Charter of 1606, licensed the colonization of a tract of land from 34° North to 45° North, a distance of 660 miles, while the later Virginia Charters extended the land grant from sea to shining sea, that is from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans. The letters patent of the Newfoundland Company awarded them the whole of that island for their venture.

Royal generosity not only permitted the prime movers ‘to have, hold, occupy and enjoy’ any ‘remote, heathen and barbarous lands’ not held by any Christian people but also allowed them the right to sell on vast areas of them. Thus John Dee stated that ‘Sir Humphrey Gilbert granted me my request to him made by letter, for the royalties of discovery all to the north above the parallel of fifty degrees of latitude’ – that is present-day Canada, stretching upward from a line drawn between the mouth of the St Lawrence River and Vancouver Island. Further south Gilbert assigned some 8.5 million acres of his potential holdings on the mainland of America to Sir George Peckham and a further 3 million acres to Philip Sidney, who promptly offloaded 30,000 of them onto Sir George. Nor were poorer potential planters to be left disappointed. The Virginia Company, for example, ensured reasonable tracts of land would be made available to those who purchased shares in their enterprise or who were prepared to sail to the new world to work for themselves or to serve a period, usually seven years, as indentured labour. Even convicted criminals and the indigent were to be offered the chance to start afresh in pastures new. A new world and a new life beckoned and yet the gap between the size of the area granted in the Charters and the land which was actually grabbed was enormous for, by 1630, at the end of all this gracious royal distribution, the English occupied the banks of one river, the James, and a number of bays. So, with only effort or ambition providing a boundary for their acres, the questions that have to be asked are: why did the newcomers take so long to establish their domains, and why did they so frequently fail in their endeavours so to do?

Spain, the other nation with major American interests, moved with far greater rapidity than did England. In September 1498 Christopher Columbus, on his third voyage, became the first European to set foot on the mainland of South America when he stepped ashore on what is now the coast of Venezuela. A year previously, on 24 June 1497, John Cabot, a Venetian in the service of Henry VII of England, became the first European since the Vikings five centuries earlier to set foot in North America, when he was rowed ashore, probably somewhere in Newfoundland.

Although those dates are so very close to each other, what happened in Spanish and English colonies in the next ninety years differed greatly. In that time Spain conquered three American empires and each year ferried back a fortune that easily exceeded the total annual income of the English Crown. The English did not return to the land until the very end of the period, for just two years, merely as sojourners who failed to make any private profit for the small group of investors who had placed their funds and their faith in the venture. Thus, while New Spain became the financial salvation of Old Spain, the English settlements on the western Atlantic littoral were never more than an eccentric sideshow for the Tudor and Stuart court.

The phrase ‘British Empire’, coined in 1577 by John Dee, gives the impression that Britannia wished to set her bounds wider still and wider for the glory of Queen, country and the Protestant creed. The actuality is far removed from the vision. The early argument for overseas settlement was based around: finding a passage to Cathay; discomforting Spain; settling indigent or criminal elements; monopolizing the distant fishing grounds; searching for precious metals and resettling loyal but non-Protestant groups. All of these could claim to be endeavours in the national interest, but the overweening desire of those masterminding the venture to Virginia was selfaggrandizement. This was the age of avarice, when lesser gentry, who were loath to besmirch themselves with trade, sought other ways to enrich themselves, preferably through the hard work of others. Henry VIII had answered this craving for some, through the dissolution of the monasteries, which freed great estates for his courtiers to grab. By Elizabeth’s reign this source had dried up but, fortunately, three new founts of both wealth and land arose to fill the gap. The first was being carried in the holds of Spanish and Portuguese ships returning deep-laden from the Indies. The second was the great estates of Ireland, which were being made available to ‘planters’ once the rebellious previous owners had been evicted. Thus, those who wished to encourage the third – the settlement of America – had to compete with the more rapid and richer returns from piracy and the closer proximity of Irish estates. Added to this was the fact that the distant unknown land area available for the English to experiment with settlement in America had been selected for them by the Pope and the Spanish.

In 1494, to settle a dispute between Spain and Portugal over global hegemony, Pope Alexander VI brokered the Treaty of Tordesillas, which drew an imaginary line through the Atlantic Ocean 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands, granting lands discovered to the west of this line to Spain and those to the east to Portugal. This separation of interests between two potentially conflicting nations rendered both of them an added service, for it encouraged them to develop only their own hemispherical rights: Portugal, trading in the east and Spain exploiting and extracting in the west. The English, with no legal area to call their own, tried to spread themselves thinly over both regions, incorporating both an East India and a Virginia Company, with not enough funds available to ensure that both could thrive.

No sooner was the papal curtain drawn than the English began to consider ways of getting around it to reach the markets of Cathay, but it was not until eighty years later that Francis Drake, passing through the Straits of Magellan in the far south of America, showed how it was possible both to prey on the Spaniards and to reach the eastern markets. Others considered similar outcomes could be achieved by a much shorter journey through a northwest passage over the ‘top’ of America. This mythical passage would occupy many English minds and cost the lives of several English mariners while those who thought of America as an obstruction and not an opportunity refused to be convinced by the evidence of the survivors. In this the English differed from the Spanish for, although Columbus had sailed west to discover a new route to the Indies, when he failed, the Spanish were, understandably, content to concentrate on the serendipity of wealth their new discoveries could bring them and which they were determined to protect from any intruders, which was their second contribution to the English choice of settlement site.

Both the English and the French knew that for any of their plantations in North America to survive they needed to be both distant and hidden from Spanish forces. The French ignored this and paid the price when, in 1565, the Spanish exterminated their colonists at Fort Caroline in Florida. News of this massacre created a quandary for those planning the first English settlement which, while needing to be accessible to the sea for succour, would also need to be secure from assault from that quarter as well. Yet, when it happened, that assault would be launched by the native people whose objections to the arrival of the English none took into account.

It is a strange paradox that the Spanish wiped out three developed civilizations – Inca, Maya and Aztec – with brutal ease, whereas the English, confronting a native population which they regarded as ‘savage’, took far longer to overthrow their opposition. The obvious answer is a simple one: the nations with a developed infrastructure collapsed when their social fabric was ripped apart and their buildings razed; those who could live off the land as hunters and gatherers could abandon their settlements and move on with greater ease, while still being able to assault the fixed dwellings of the interlopers who had no such native skills. In America this led to a war in the woods, a type of warfare which the English, throughout their long sojourn on American soil, were neither comfortable with nor prepared for. By not acknowledging that they were invading a foreign land and planning accordingly, the English guaranteed failure for five major reasons: lack of original numbers; unreliable reinforcement and resupply; failure of local self-sufficiency; the inability to overawe the enemy and a lack of leadership. In the end they overcame these, but it would take a long while before they were confident enough to move on from the beachhead and wrestle control of a continent from a group who were less numerous, less united and less industrialized than were the invaders. The final conquest would take several hundred years to achieve, with victory coming, not through conversion, persuasion, integration or inter-marriage, nor from any form of superiority, apart from the gun, weight of numbers and grim and implacable hate. When the numbers and weaponry were better matched, the outcome was often far different. The war was finally won because the English tribe outbred its opponents. For, whereas disease, one of the invaders’ allies, was capable of devastating an Amerindian village or confederacy beyond the stage where it was capable of recovery, when it decimated English colonies they survived because reinforcements were ferried out to them from the unlimited English pool of labour, although these seldom included sufficient soldiery for the immediate task in hand.

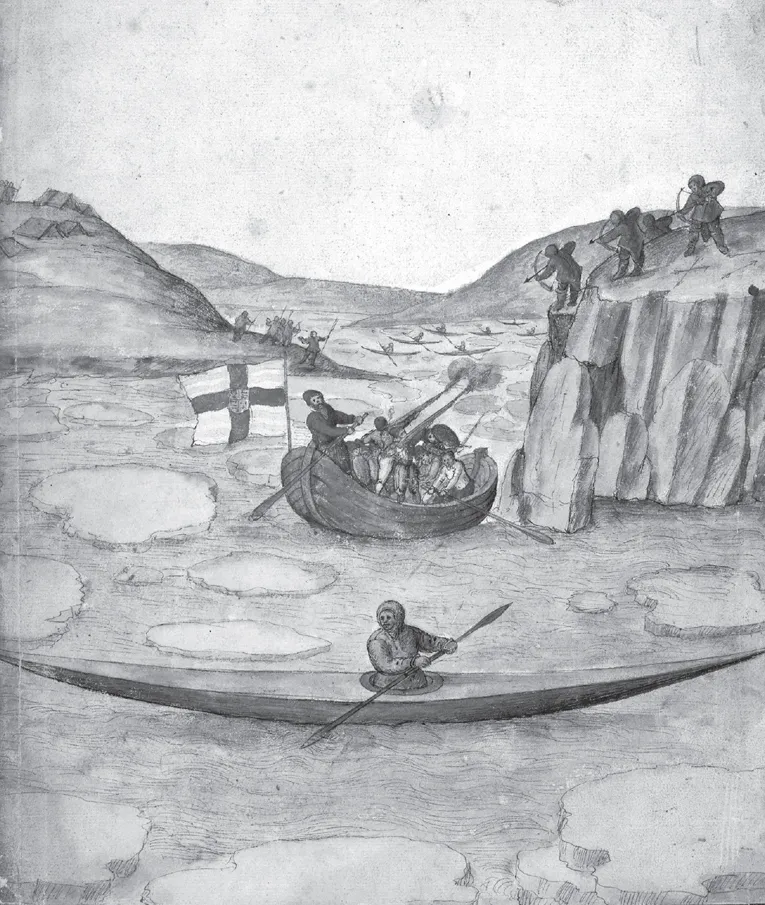

Frobisher at Bloody Point. From the beginning native opposition to English landings was strong enough to dismay but never powerful enough to deter. (British Museum)

Spain was a military nation with a professional, ruthless army that had been at war for generations. This brutal tradition its conquistadors took to New Spain where, it has been estimated, between 1519 and 1600, they reduced the population of that region from 25 million to 1.5 million. Even allowing for the fact that they were operating in a far less densely populated area, the English did not cause such commensurate devastation. They were different. For one thing, they did not possess a professional army and it showed. It was not so much that few English troops could be spared to spearhead an invasion of America but that so few such practitioners of the profession of arms existed in England that none was available for what was, essentially, a sideshow. Only Ralph Lane, who was summoned from Ireland, was a professional soldier: John Smith and Miles Standish had been schooled as mercenaries. Neither would any experienced or senior soldiers have felt honoured by being offered the command of such petty numbers as were deployed.

Spain also possessed, in the Jesuits, a priesthood that was as much an arm of the state as the army. Together this holy alliance slaughtered and subdued all of that part of southern America with which they came into contact. The English did not possess a proselytizing organized priesthood. Whereas Spain held to one true and exportable faith, the English struggled to know what to believe and on whom to impose that belief. One result of this was a reduction in the number of people in holy orders who could be spared to accompany settlers heading for America. Those that did were, for the most part, fully occupied with the bodily and spiritual survival of their own flock.

It is not only in comparison with Spain that England’s slow advance across America seems sluggardly. The nation had had its own experience of invasion recorded in the shadowy tattered texts of its distant historic past, each with its own significant impact on the indigenous inhabitants. Yet, whereas the Romans, Saxons and Normans had flowed tidally across England in successive and successful waves, the English assault on Virginia was splattered across the shoreline like spray breaking on impermeable and impregnable cliffs which, for all its initial force, is dissipated well before it trickles inland.

The Claudian invasion of England took place in AD 43: Hadrian’s Wall, which marked the final frontier between Roman England and Pictish Scotland, was built between AD 122 and 133. The Germanic tribal chiefs Hengist and Horsa landed in Kent in AD 429; the Battle of Catterick, which confirmed Saxon suzerainty over England, was fought in AD 590. William the Conqueror arrived at Pevensey in 1066 and could claim he controlled all of England by 1070. By contrast, although Cabot arrived off America on his mission of conquest in 1497, it was not until the Crown took control of southern Virginia in 1625 and Winthrop’s Massachusetts Bay settlers arrived in 1630 that it could be said with any certainty that the English occupation of a small part of America was even reasonably secure.

Although different in many ways, those three ancient invasions shared an ingredient of success – numbers. The Romans had landed in Britain with four legions, about 25,000 men; the Saxons brought a whole people over in successive tides, most of whom were strong enough to overcome local resistance; William took a gamble with numbers but still brought 3,000 followers with him to Pevensey to conquer an island kingdom. Yet, although Sir Humphrey Gilbert suggested a figure of 5,000 troops would be needed to challenge Spanish domination of the new world, Sir Walter Ralegh dispatched a company of 107 men, to conquer a continent, and a village to settle Virginia. It is not surprising, therefore, that failure rather than success was the reward for these efforts and that few inroads were made away from the shore.

This lack of penetration has meant that, while historians talk readily enough about the Age of Invasion that followed on from the Roman withdrawal from Britain, few apply the same term to the period of English settlement in America following the grant of a Charter to John Cabot. Yet both involved landings from the sea, the seizing of land and the subjugation of the native population who were driven eventually either to extinction or into wilder unwanted lands.

The only difference, apart from the fact that one invasion took place in the dark abysm of time, is that whereas the Saxons arrived as kindred groups wishing to farm and achieve self-sufficiency, the English initially arrived in America to provide profit for absentee landlords, who were almost disastrously incompetent in the planning, execution and support of their operations. Only when the Mayflower settlers arrived in 1620, with a similar mindset to their Anglo-Saxon forebears, determined to establish a close-knit domestic community and not return home, did a successful, permanent and self-sufficient settlement in America seem likely. Up until then the English had established beachheads which they always struggled to hold and were often forced to evacuate.

Thus, from the start the English planned an approach to settlement that differed hugely from that being pursued by Spain in South and Central America. There the strategic plan was to exploit, extract and export, for the benefit of the Crown whose servants the settlers were. This had the great advantage that neither soldiery nor money were to in short supply, and that an identifiable and understood political and military hierarchy ordered and governed each settlement, town, city, mine and enterprise that Spain undertook. It also meant that the native population, who had little to offer the enterprise once their wealth had been seized, could be treated with ruthlessness, their extermination being compensated for by the importing of slaves from Africa. Most of all, New Spain succeeded because it was rich in highly sought-after commodities, especially go...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Five-Finger Exercise

- Chapter 2: Dreamers and Schemers

- Chapter 3: The Charters: Come Over and Help Yourselves

- Chapter 4: Planning and Site Selection

- Chapter 5: Ships and Sailing

- Chapter 6: Pilotage and Navigation

- Chapter 7: The Crossings

- Chapter 8: Fortress America

- Chapter 9: Reinforcement and Resupply

- Chapter 10: Extirpation, Evacuation, Eviction and Abandonment

- Chapter 11: The Amphibious Campaign

- Chapter 12: Piracy

- Chapter 13: Joint Command

- Chapter 14: Summary

- Appendices

- References and Bibliography