eBook - ePub

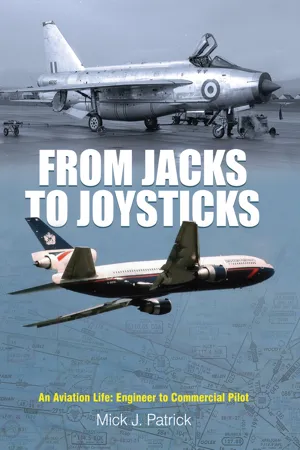

From Jacks to Joysticks

An Aviation Life: Engineer to Commercial Pilot

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Trenchard Brat. Flying Spanner. Left Hand Seat. Nicknames abound in aviation. But not many get to be called them all, especially when theyve started life with an aversion to school and a stammer thrown in. Mick Patrick started his aviation career as an RAF Apprentice and finished it as an Air Ambulance pilot. He never knew he was going to become a pilot just that he was determined to have a good start in life and it seemed the RAF offered this to him.As an engineer, Mick saw active service on jungle airstrips in the Far East during the Borneo Confrontation with Indonesia and got his hands dirty servicing Cold War aircraft. Later he had an opportunity to become aircrew as a Flight Engineer and it was from this position he was able to use his knowledge as part of a crew to take the next step. After many years of watching pilots ply their trade, Mick decided he could do it too, so worked his way up to becoming a commercial pilot.Along the way he experienced risky moments that shaped him as an aviator; he crashed a float plane in a Texas lake, flew casualties to Coventry and elephants to the East, nose-dived in Nassau and skirted death at Stansted. The tales in this book are used to illustrate how they affected Micks approach to aviation and what he took away from those events.Immensely readable and delivered by a true story teller, From Jacks to Joysticks is for anyone who loves tales of aircraft and life in aviation, whether in the cockpit or on the ground. Above all else this book is about how a lifetime of exposure to aviation has shaped one mans thinking and approach to life and how in aviation you need to keep an open mind.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Jacks to Joysticks by Michael John Patrick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Air Force Family

The Boeing 707 rolled into a new heading and levelled off. The engines spooled up to maintain airspeed with a muted roar. There was not much turbulence but every so often the wings dipped ponderously in response to the gusts coming out of the line of thunderstorms on our starboard side. It was mid-afternoon at Houston, Texas and a long squall line of storms blocked our approach. The air was full of static and the radio frequencies were full of the sound of sizzling frying pans punctuated by a splat of lightning discharge. I heard a rise in the frying pan volume and a sudden close splat of electrical energy somewhere down the aircraft.

There was none of the usual aircrew banter on the radio with the Houston Terminal Radar Controller that is so typical of that side of the pond. Americans love to jazz up the exchanges with Air Traffic Control. But there was none of that today. The atmosphere in the cockpit was tense. We had weather radar and it was painting all the colours it could, including magenta, denoting the centre of the storm cells. There was a lot of magenta.

We were on Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON) steers. The US controllers are expert at guiding aircraft through bad weather but today it was never going to be a smooth ride. Despite the time of day the air was dark and malevolent.

Suddenly another sizzling reached a crescendo and we got hit just below the right side of the cockpit with what sounded like a sledge hammer hitting an empty metal dustbin. The clouds lit up briefly and temporarily blinded us from the view ahead.

Simon in the right seat never flinched. No one said anything to each other. I swore softly to myself and checked around the cockpit to make sure we had not lost any systems. The instrument panel compasses all agreed with the basic standby compass. So far so good.

It was time to make the big turn to the airport to pick up the Instrument Landing System for the landing runway. TRACON give us a new heading to fly and the 707 dipped the right wing to make the turn. We plunged into dense cloud. Rain was streaming over the windscreens. We had wipers but they are ineffective in those conditions. In any case we would have them selected on during final approach. The clouds lit up bright white and with virtually no announcement on the ether, the lightning hit us hard on the nose, exploding the fibreglass laminated nose radome and burning out the radar scanner inside. Our waveguide from the scanner to the radar screen in the cockpit dutifully transmitted a message of thousands of volts to the screen which flashed a brilliant white then went black.

We were blind, but our progress to the airport was being steered by TRACON. A further turn and another short descent on the Instrument Landing System (ILS) gave us a cloud break at about 700 feet above Houston airport. There in front of us was the rain soaked and windswept runway under a leaden sky. I turned the windscreen wipers on at the captain’s request. Nearly there.

My life was not meant to turn out like that. I thought that I was going to be a farmer. However, it didn’t happen so I drifted into aviation for no other reason than that my family had a lot to do with the Royal Air Force. It would be nice to say that I always had designs on being a pilot but that would not be true. If there was any common thread from engineer to commercial pilot it is simply because I took any opportunity that presented itself and one thing led to another.

The fact was that as a kid I had no idea where I was going in life. Academically I was just above the poverty line – but something told me to get a good start in life. However, I just did not have any idea what that entailed and no-one else seemed to know either. When I asked my father for guidance he just told me to do whatever I wanted and went back to the Daily Telegraph. My mother wasn’t much help either.

Dad had joined the RAF in 1926 after the Royal Navy had ignored his application. He said it was in a fit of pique that he turned to the Air Force. His service took him to Egypt where he met and married a woman who was never referred to in my childhood. He lost her to a brain tumour, apparently. They were childless. I think that hurt so much he did not want to bring it up except to explain it to my mother when they met. I don’t blame him. Some things are best left.

Dad went on to serve in the RAF as an administrator, leaving the service in 1953 retiring in the rank of flight lieutenant. He was Mentioned in Dispatches twice during World War II. Never one to talk about it – like so many others – he would only speak about it to those who shared the experience. I can only assume he was mentioned for initiative and hard work. He was that sort of bloke. From what I can glean the first citation was for hard work in England in the first years of the war and the second was something to do with Belgium and the Battle of the Bulge where Allied intelligence failed to discover a German armoured thrust which drove the Allies back in disarray until the line held once more. We used to joke that he saved the typewriters, but apparently the withdrawal he conducted with his unit was made in good order with the German armour only just down the road. I have his citations and medals and I am rather proud of him.

Mum left school at the age of 14 and entered service. By that, I mean like Upstairs, Downstairs. She became a ladies companion which I suppose gave her a leg up to one above ‘cook and bottle washer’.

Not much else seemed to have happened to her that I know about but she met and married a Mauritian chap and settled down to have two children with him – they would be my elder half brother and sister. Then misfortune struck her as well, as her husband died of a heart attack whilst her children were only about six or seven years old. This heart defect was passed on in the genes and both my elder brother and sister were not to live long lives either.

Mum joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, along with her sister, and like my father before her, found a sanctuary and a family. No plotting room for her, she did the menial stuff which runs a wartime RAF station but took to it like a duck to water. I know she spent some time on a bomber station because in a rare moment of reflection, she did say to me how hard it was when the bomber crews did not come back.

By the time my mother and father met he was a warrant officer and my mother was a flight sergeant in charge of WAAFs at RAF Northolt.

Mum related a story to me how she had gone off the station to do a stock check on stores held in a shop in the high street in Northolt. It was custom and practice to place stores in various places to offset losses if the station got attacked, which of course many were. She told us how she was walking down the street towards the shop and heard a roaring sound behind her coming up fast. There was no time to turn round as a Heinkel bomber passed over her very low right down the road and she had a clear view of the gunner in the lower turret who was shooting the place up. Apparently she threw herself on to the floor of a shop and it was all over in a flash.

On another task, she was given a briefcase full of top secret documents. A car was provided and she was driven to Bletchley Park in Milton Keynes and delivered the contents to an orderly room at the entrance, where a receipt was given in exchange for the briefcase. At the time, of course, the whole thing was shrouded in mystery but a long time after the war, when secrecy was gradually reduced, she learned that the papers had been delivered to the code breakers and analysts of the wartime intelligence centre credited with shortening the war by four years.

I came along in 1942 and of course Mum had to retire from the WAAF in which she had done so well. She would tell me in jest, years later, that I had ruined her career. At least I think she was joking. I blame my father.

As my father was by then serving at RAF Castle Donington (now known as East Midlands Airport), my birth, in November 1942, took place in a small maternity hospital nearby called Lockington Hall. This grandly titled, though rather small, manor house had been owned by the family of Lord Curzon, one time Viceroy of India and Foreign Secretary and had been offered to the nation for wartime use. In fact, the premises provided the address for a great many birth certificates long after the war ended. It is now the offices of a local company and there is a thriving website connecting all the participating ‘Lockington Babes’ together.

Not all the babes had such clear family connections. Many of the ladies who attended there came from the East End of London and elsewhere. Some of those families were kept apart for many years because of the turmoil of war. Sometimes the returning demobbed servicemen would come back to a larger family than they had reckoned on.

My earliest childhood recollections are of what was then called “billeting” and for us it was in the pub known as the Barge Inn on the Avon and Kennet Canal near Devizes. The Barge Inn had upstairs accommodation and my mother and I were parked there while Dad spent time at RAF Boscombe Down and then went off to France after D-Day in 1944. He was attached to Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Air Force (SHAEF), later moving through Belgium and eventually Germany as part of the occupation forces.

I have hazy memories of farm workers in the public bar sitting on benches with twine wrapped round their trousers just below the knee. Apparently, this was to prevent rats in the farm from running up their trouser legs while they were moving hay. They would have a pint of bitter in hand and I got a sip out of each one. I know they thought it was fun and so did I but if mum caught me doing it, there was trouble. I have enjoyed a drink or two for the rest of my life.

Another vivid memory was my near demise in the waters of the canal outside, thereby closely emulating my mother’s brother Len, who drowned in his childhood in just such a canal in Birmingham. There was a hand cranked footbridge across the canal a short distance away and I used to sit on the edge of it while the man operating it wound it back to connect to the other bank. When it linked to the other side it would come to an abrupt halt and lock in place. For me it was a bit too abrupt and I shot into the water from the sitting position. I remember the greenish colour of the water and hearing bubbling noises. The chap got to me just as I was going under for the third time and I shot back out of the water as he caught me by the scruff of the collar and pulled me clear. After a bit of spluttering, apparently I was OK.

People wanted to know what I had seen and felt and I told them that I had heard the fishes talking to me. At least that was how I interpreted the bubbles I was making under the water. Mother must have been beside herself - what with that and me eating the bait worms when we went fishing.

1944 saw us in a basement flat in Regent’s Park next to the main railway line. It is not far from the London Zoo and the man upstairs was the head keeper for the seal house. There we lived in a “Borrowers” sort of existence looking up to the pavement outside and seeing people’s feet as they walked by. We had a tin bath for bathing and an outside toilet next to the coal shed in the space between us and the pavement above known as the “area”.

This was after the invasion of Europe had taken place and Mr Hitler was lobbing V2 rockets at London in the misguided hope of bringing us to our knees. On the railway line at the end of the road there was an anti-aircraft gun pulled by a train which ran up and down the line conveniently in the flight direction the rockets took.

Listening from underneath the dining table, the noise of the gun was rather exciting as it banged away at the targets.

VE Day came on 8 May 1945 and I have a picture of me, now at the age of two and a half, sitting in the back garden surrounded by Union Jack flags. So we were not to be occupied by the Nazis after all and I would not be required to be a member of the Hitler Youth.

The war had ended but mass migrations were going on in Europe and we were making a huge effort to get back on our feet. Little improved for some time and bomb sites in London remained uncleared, not rebuilt for many years. I recall housewives wearing headscarves over their curlers buying eels at a fish stall in Kentish Town. Eels would come out of the bucket writhing in the hands of the fishmonger who would cut them into short lengths for his customers. I was fascinated by this and how each short piece of eel kept twitching as he wrapped it up in newspaper.

I also used to wonder if the customers ever took the curlers out – and if so, why?

Eventually Father had arrived in Germany through the aforementioned travels as part of what was then called the British Air Forces of Occupation, British Army of the Rhine. His sector and responsibilities lay in Bückeburg, near Hannover. Now that Mother had tracked him down to an address of some permanence she pressed for the opportunity to join him and it came to pass that we joined him as a service family billeted in a substantial house with another officer’s wife and children. Father had by this time been commissioned and held the rank of flight lieutenant. I assume that he had been doing fine without us and enjoyed his part in the war but now Mother had the domestic reins back in her hands, Father’s life was now probably more regulated.

I had a BAFO identity card issued to me (Height 3 ft. 2 inches) in 1948 and a school report from the British School in Bückeburg read ‘F’, ‘Good’ and ‘V’. Good in class, so I must have been doing OK.

There are only a few memories of that house and life in general. One concerned the owner of the house. Although having been ejected from his property, he was allowed to maintain the garden and, in particular, to grow some food in it for himself. One day, in a mood of reconciliation my mother made some toffee apples and sent me out to the man in the garden with a tray of these toffee apples to offer him and make peace. I recall quite clearly his reaction at the offer made as he shouted, “Nein!” Taking the toffee apples back indoors I informed Mother of the failure of our attempt at detente.

Another memory is being caught playing ‘doctors and nurses’ rather too enthusiastically with the little girls of the other family in the house. Things were a bit tense after that.

Life drifted peacefully along and my parents must have been glad to see each other because in 1946 my mother delivered a baby girl, presenting my father with a daughter and me with a younger sister.

By the summer of 1948 we were back in London, initially in the basement flat again in Regent’s Park. Father was posted to various air force stations and we remained in the capital. I remember some appalling fog, which some Americans still seem to believe we live in, when I could not cross the road and keep both pavements in sight. In the middle you were just in limbo and had to steer the same course in order to stumble eventually upon the other side. I was issued with a National Registration Identity Card. I’ve no idea why, I suppose it was all part of the new post-war Britain.

Mother’s determination to secure us better housing paid off and we were allocated a top floor flat in Kentish Town. It was opposite a factory building with huge windows, which gave light to the production of Lilia sanitary towels. Sitting in our flat we could watch the workers at the conveyor belts boxing up the products if we had nothing better to do.

I was enrolled at a very Victorian primary school which I found very depressing. Initially in 1950 my school reports were not too bad and my reading in class got a “Very Good” with a “Reads very well” comment. By 1952 I was only “Very Fair”.

Between those two dates I had developed quite a bad stammer which held me back from achieving scholastic greatness, while socially it was a bit of a drawback. That affliction stayed with me well into my thirties and prevented me from advancing as I might have done. As for the cause of the malady, I can only conclude that I remember being chased up the stairs by a Staffordshire bull terrier. I think it was only enjoying the chase and meant me no harm, but my reaction was of outright terror. I ran to our flat door, which was closed. By this time I was hysterical and was screaming my head off for my mother to let me in. She did so and chased the animal away.

On one occasion during my rather sad time at this school we had to read out loud in class. I started well – if I could just hold my nerve for long enough I’d be able to get through it until it was someone else’s turn. Unfortunately I looked up and saw the teacher looking at me and that was enough to stem the orderly flow of words. My throat locked up solid on the word ‘and’. There was no credit given for the several apparently faultlessly read paragraphs that had preceded this impasse and I was now stuck fast, unable to utter another word. The method by which I was now to learn to read and remember the word “and” was for my teacher to beat me on the bare leg with a ruler.

Following that episode I played truant for two weeks and used to walk miles to watch trains shunting at Chalk Farm railway station or to wander round Hampstead Heath. All of this was a bit dodgy for a lad of 9 years old but no-one found out until at length, out of boredom, I would go home too soon and make excuses about how we had got out early. Of course when Mother checked with the school they said I had not been there for two weeks. I was rumbled and things were a bit tense again.

My newly acquired stammer caused a bit of a communication problem. Where words were difficult to eject, anything starting with an ‘F’ seemed to come out OK, so it was all “`effin this” and “`effin that”. Is that the origins of Tourette’s? I don’t know, but I still seem to have a bit of it. When I refer to it as a stammer that’s not really what my affliction was: the effect was like something having a strangle hold on my throat and no words could come out. What usually preceded it was the build-up of stress before some event where I was to say something in public with all the attention on me. I would therefore go to extreme lengths to avoid encounters of that kind and continued to do so for many years, even into my thirties. People seem to find a stammer joke hugely funny. I still wince and feel uncomfortable.

By this time my elder brother and sister had been returned to us from their wartime accommodation in the country out of harm’s way. As we were a bit tight for accommodation and did not much cherish the view into the sanitary towel factory, my ever-resourceful mother persuaded the council to move us into another flat in Kentish Town. Eventually, she wangled us into a nice semi-deta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter One Air Force Family

- Chapter Two Apprentice Airman

- Chapter Three Cornish Air Force

- Chapter Four Far East Confrontation

- Chapter Five Reluctant Return

- Chapter Six Civvy Street

- Chapter Seven Hangar to Cockpit

- Chapter Eight Cyprus and the Gear Not Locked

- Chapter Nine The Stars Go Sideways

- Chapter Ten Airprox in a DC10

- Chapter Eleven In the Front Seat

- Chapter Twelve Aircraft Shares

- Chapter Thirteen Ambulance Driver

- Chapter Fourteen Instructor at Large

- Chapter Fifteen IATA Auditor

- Chapter Sixteen Libyan Lessons

- Chapter Seventeen Dawn Over Kabul

- Appendix

- Plate section