- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Armies of the Napoleonic Wars

About this book

This authoritative military reference provides detailed analysis of the various armed forces that fought in the Napoleonic Wars.

The Napoleonic Wars were some of the most devastating and consequential in modern European history. Yet for all the attention paid to these dramatic conflicts, little focus is given to the composition, organization and fighting efficiency of the armies who fought them. Each force tends to be examined in isolation, either in the context of an individual battle or as the instrument of a single commander. Rarely have these armies been studied together in a single volume as they are in this fascinating reassessment edited by Gregory Fremont-Barnes.

Leading experts on the Napoleonic Wars have been specially commissioned to produce an in-depth analysis of a specific army. The result is a vivid comparative portrait of ten of the most significant armies of the period, and of military service and warfare in the early nineteenth century. The volume covers the armies of Austria, Britain, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw, France, the Kingdom of Italy, Portugal, Prussia, Russia and Spain.

The Napoleonic Wars were some of the most devastating and consequential in modern European history. Yet for all the attention paid to these dramatic conflicts, little focus is given to the composition, organization and fighting efficiency of the armies who fought them. Each force tends to be examined in isolation, either in the context of an individual battle or as the instrument of a single commander. Rarely have these armies been studied together in a single volume as they are in this fascinating reassessment edited by Gregory Fremont-Barnes.

Leading experts on the Napoleonic Wars have been specially commissioned to produce an in-depth analysis of a specific army. The result is a vivid comparative portrait of ten of the most significant armies of the period, and of military service and warfare in the early nineteenth century. The volume covers the armies of Austria, Britain, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw, France, the Kingdom of Italy, Portugal, Prussia, Russia and Spain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Armies of the Napoleonic Wars by Gregory Fremont-Barnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The French Army

Apart from the German Army of the Second World War and the Union and Confederate forces of the American Civil War, one may assert with confidence that more ink has been spilt to describe the French Army of the Napoleonic Wars — and, specifically, its principal component, the Grande Armeée — than any other fighting formation in history. Works by Elting, Forrest, Haythornthwaite and Rogers, to name but a few, have shed considerable light in general terms, while dozens of other authors have explored virtually every conceivable aspect of the subject, from weapons and commanders to tactics and uniforms; from unit histories and command structure to battlefield studies. Nevertheless, the organisation of the principal arms of the French Army — infantry, cavalry and artillery — has remained less well documented, the detail often spread across numerous campaign histories rather than analysed as a discreet subject in its own right. This chapter therefore seeks to examine this neglected aspect of French forces in the decade between Austerlitz and Waterloo — at regimental, brigade, division and corps level, throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

Having said this, as this treatment must compete here for precious space beside studies of the other principal fighting forces of the era, it must necessarily restrict its parameters accordingly, and thus confines itself to the regular units of the French Army, as well as of the Imperial Guard, excluding thereby the various provisional, National Guard and foreign units which at different stages of the wars composed part of the Emperor’s forces.

INFANTRY

Infantry was organised into regiments, which for both the line (Reégiments d‘Infanterie de Ligne) and light regiments (Reégiments d’Infanterie Leégeère) were identified by number and type, i.e. 1ère de Ligne, 4eme Leégère. Infantry of the line was composed of centre companies, known as fusiliers, light companies, known as voltigeurs, and elite companies composed of grenadiers. Leégeère battalions (usually styled simply leéger) were structured similarly, although the centre companies were known as chasseurs and the elite companies termed carabiniers. At the start of the Austerlitz campaign the regular infantry were organised into 89 regiments of the line and 26 light. From 1805 until the end of the 1807 campaign, infantry of the line consisted of 1 voltigeur, 1 grenadier and 7 fusilier companies. Light battalions consisted of 1 voltigeur, 1 carabinier and 7 companies of chasseurs. On paper a company held a strength of 123 men, but in reality this figure was usually not met, even at the opening of a campaign. With an average field strength of 80 men per company, typical battalion strength therefore stood at 720 men. Line regiments were numbered from 1 to 122, though the following were unused in the period to 1807: 31, 38, 41, 49, 68, 71, 73, 74, 77, 78, 80, 83, 87, 89, 90, 91, 97, 98, 99, 104, 107, 109 and 110. Leégeère regiments were styled 1 to 31, with several unused numbers: 11, 19, 20, 29 and 30.

During the course of the campaigns of 1805 and 1806, most of the Grande Armeée served in Moravia and Saxony, respectively, with casualties replaced by the creation of new formations, which the Emperor made possible by a number of expedients, including increases in infantry regiments in the form of a third battalion and an increase in the strength of infantry companies to 140 men each. In fact, while third battalions were added to infantry regiments — a strength reached by the end of 1806 — the other measures did not come to pass. Many regiments during the campaign against Prussia in fact contained 4 battalions, but at this time most regiments contained 2 battalions, each of 8 companies, with typical battalion strength at 640 officers and other ranks. While operating in Prussia and Poland at the end of the year, the Grande Armeée consisted of forty-seven regiments of line infantry and fourteen of leégeère. By this time 18 infantry regiments had 4 battalions instead of the standard 3. Moreover, by detaching a company from each of the third battalions of regiments operating in Germany, eight provisional battalions were formed. Once they reached Poland they were disbanded, their men distributed among other battalions to make up losses. For service in the rear on garrison duty and for security functions, Napoleon ordered the formation of another twenty provisional infantry regiments.

Increased strength was achieved by deploying units from allied armies, including those of the Kingdom of Italy, the Duchy of Warsaw, the Kingdom of Holland and the Confederation of the Rhine. Replacements for losses came in the form not simply of recruits, but by shifting completely French formations from Italy, which apart from the British landing in Calabria in the summer of 1806 remained quiet of conventional fighting. Garrisons in Italy duly furnished two divisions of infantry, totalling eight regiments, while troops garrisoning Naples were moved north to replace them. Further divisions were formed by denuding port garrisons across France and across the Empire, with replacements acquired from reserve forces and conscripts.

During the period between the end of the Friedland campaign and the war against Austria (i.e. the summer of 1807 to the spring of 1809), Napoleon sought to re-organise and enlarge his armies, a process that began after the conclusion of peace with Russia and Prussia at Tilsit in July 1807. Line infantry regiments were recast to contain four field battalions and a depot. Each battalion was reduced from nine companies to six, with the strength of each company unaltered. Thus, a field battalion consisted of 4 fusilier companies, 1 of grenadiers and 1 of voltigeurs. The depot battalion contained four fusilier companies. Napoleon’s decree of 18 February 1808 laid down the basis for this new system of infantry organisation, the first seven articles stipulating:

1. Our regiments of infantry of the line and light infantry will in future be composed of a staff and five battalions; the first four will be designated war battalions and the fifth the depot battalion.

2. Each war battalion, commanded by a chef de bataillon having under his orders an adjutant and two regimental sergeant-majors, will be composed of six companies, of which one will be grenadiers, one light infantry, and four fusiliers, and all of equal strength.

3. Each depot battalion will consist of four companies. The Major will always be attached to this battalion. A Captain, designated by the Minister [of War] from three candidates selected by the Colonel, will command the depot battalion under the orders of the Major. He will at the same time command one of the companies. There will be in the depot an adjutant and two regimental sergeant-majors.

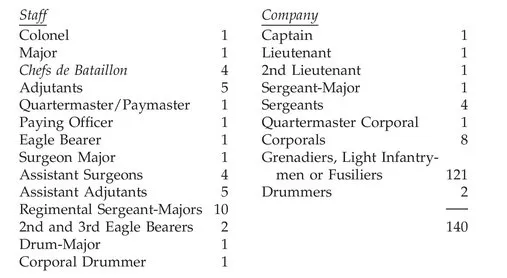

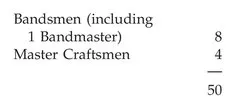

4. The strength of the staff and that of each company of grenadiers, of carabiniers [in a leégeère regiment], of light infantry, or of fusiliers is to be as follows:

Thus, the strength of each regiment will be 3,970 all ranks, of which 108 will be officers and 3,862 NCOs and men.

5. There will be in each war battalion four sappers who will be chosen from the grenadier company of which they will continue to form part, and there will be a corporal who will command all the sappers of the regiment.

6. In battle the grenadier company will be on the right of the battalion and that of the light infantry on the left.

7. When the six companies are present with the battalion it will always march and act by divisions. When the grenadiers and light infantry are absent from the battalion it will always manoeuvre and march by platoon. Two companies will form a division; each company will form a platoon; each half company a section.1

This process of re-organisation proceeded slowly and did not reach its conclusion until 1809, in the months just preceding the campaign against Austria. Regiments situated in distant garrisons were naturally the last to be affected by these reforms. Even after a fourth battalion was created, it was not uncommon for a regiment to be divided such that some of its battalions served in one theatre while others operated elsewhere. In cases of pressing need, the depots sometimes were required to form new battalions. As well as adding a fourth battalion to infantry regiments, the army increased in size between Tilsit and the commencement of the Austrian campaign as a result of the growth of the Empire, drawing in other nationalities and converting reserve or provisional units into those of the line. Thus, at the start of the campaign, while the army was simultaneously engaged in Spain and Germany, the regular infantry consisted of 100 regiments of the line and 26 leégeère. Most infantry regiments by this time consisted of the regulation 4 battalions plus a 4-company depot, giving it a full complement on paper of 108 officers and 3,862 men, though 3 line regiments (the 26th, 66th and 82nd) boasted 6 field battalions as well as a depot. Light infantry regiments had in almost all cases 4 battalions, though the 32nd had only 3 plus a depot. Light battalions remained organised on the basis of 9 companies. With the increase in Reégiments de Ligne, the numeric sequence of these formations was simply extended rather than assigning troops to vacant numbers. Growing numbers also dictated that new regiments include — or be wholly composed of — foreign troops, as indeed proved the case with the first one created (the 113th Line), raised in northern Italy.

In 1810, after the conclusion of the campaign against Austria, the army consisted of 105 line infantry regiments and 23 leégeère, though by the end of 1811 this had been increased to 114 of the line and 25 leégeère, for a total of 139 — made possible by the annexation of Holland and areas of northern Germany, and by raising new units in the territories of French allies. Line infantry regiments were numbered up to 129, with their light counterparts to 33. With the incorporation of the Dutch Army into the French the 123rd to 126th line regiments were created, as well as the 33rd Light Infantry. All these new units contained four battalions, in conformity with other entirely French regiments. The 112th Line was raised in Belgium, while Piedmont produced the 31st Leégère and the 111th Line. Finally, parts of northern Germany annexed to the Empire supplied the 127th, 128th and the 129th Regiments of the line. In 1811, with war looming against Russia, Napoleon ordered the creation of fifth battalions for line and leégeère regiments, as well as the attachment of two to four 3lb guns to each regiment, though these changes could not be completed before the invasion began in June 1812, such that many regiments crossed the Niemen still composed of two to four battalions with no attached regimental artillery.

For operations in Russia some regiments of line and light infantry had reached the specified total of 5 battalions, such as those in Davout’s superb I Corps, consisting of 5 infantry divisions, each of 3 or 4 brigades. 1st Division had 15 battalions, 2nd Division 17, 3rd Division 18 battalions, 4th Division 14 battalions and 5th Division 20 battalions. II Corps contained 3 infantry divisions: 6th Division had 4 brigades with a total of 12 battalions; 8th Division had 2 brigades with 16 battalions; thus, in this case, some regiments were composed of only 3 or 4 battalions, not the officially established 5. The 9th Division contained 3 brigades of Swiss and Croatian infantry, with 17 battalions all told. III Corps, under Ney, contained 3 infantry divisions. The 10th contained 3 brigades, totalling 16 battalions; the 11th consisted of 3 brigades with a total of 18 battalions, some of these Portuguese and Illyrian; and the 25th Division contained 3 brigades of Württemburg infantry — a mixture of line, jaägers (rifles) and ordinary light infantry, for a total of 18 battalions.

The infantry of IV Corps, under Prince Eugène, Viceroy of Italy, consisted of the Italian Guard of 6 battalions, plus 3 divisions of mixed French, Italian and Dalmatian infantry. The 13th Division contained 3 brigades of French and Croatian line and light infantry, totalling 16 battalions. The 14th comprised 3 brigades of French and Spanish infantry, for a total of 12 battalions; and the 15th Division contained 3 brigades of Italian and Dalmatian line and light infantry, 13 battalions in all. The infantry in V Corps, under Poniatowski, was entirely Polish, drawn from the Duchy of Warsaw and arrayed in 3 divisions. The 16th and 17th Divisions contained 2 brigades each of 4 regiments (12 battalions), but while the 18th Division also contained 2 brigades, these had only 3 regiments instead of 4, for a total of 6 battalions per brigade. The infantry of IV Corps under Gouvion St Cyr, was entirely Bavarian, organised into 2 divisions, with the 19th containing 2 brigades, totalling 8 regiments of line and light infantry — 13 battalions altogether. The 20th Division, of 3 brigades, contained 9 line and light regiments, with 15 battalions in total.

General Reynier’s VII Corps, composed entirely of Saxons, contained 2 divisions of infantry, each of 2 brigades. Those of the 21st Division had 11 battalions of line and light infantry, as well as grenadiers. The 22nd Division was composed of 7 battalions of mostly grenadiers, but also light infantry. The infantry of Prince Jeérôme’s VIII Corps, all Westphalian, was divided between 2 divisions. The 23rd contained 2 brigades with 6 regiments of line and light infantry, totalling 13 battalions, while the 24th Division had but 1 brigade, of 3 battalions of Guard infantry, 1 battalion of light infantry and 2 battalions of the line. The infantry of Victor’s IX Corps consisted of 3 divisions. The 12th Division had 3 brigades containing 6 regiments of French line and light infantry, for a total of 7 battalions, while the 26th Division had 3 brigades containing 11 regiments of Berg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt and Westphalian infantry, totalling 22 battalions. The 28th Division comprised 2 brigades of Polish and Saxon infantry, organised into 5 regiments of 13 battalions all told.

The infantry component of Marshal Macdonald’s X Corps consisted of 2 divisions: the 7th, of 3 brigades, consisted of Polish, Bavarian and Westphalian line — 5 regiments of 16 battalions in total. The 27th Division, of 3 brigades, was formed entirely of Prussians: 17 battalions belonging to various combined regiments, plus an unattached jaäger battalion. XI Corps, under Augereau, contained 5 divisions of infantry. The 30th had 3 brigades of 3 provisional regiments, totalling 22 battalions. The 31st, of 2 brigades, contained 4 provisional regiments, with 14 battalions all told. The 32nd Division, of 2 brigades, contained various French, German and Italian regiments, for a total of 18 battalions. The 33rd, of 3 brigades, contained 4 regiments of Neapolitan marines, veélites and line infantry, totalling 10 battalions. The 34th Division, of 5 brigades of French infantry and various nationalities drawn from the Confederation of the Rhine, totalled 11 regiments, in all containing 28 battalions.

Despite his massive losses in Russia, by the opening of the spring campaign in April 1813 the Emperor had assembled in Germany twelve corps of infantry (dubbed ‘Marie-Louises’ or teenaged conscripts), with an increase of two later in the year, mostly by incorporating French allied units. Most corps comprised three infantry divisions and a brigade of light cavalry. The rest of the corps served on detached duty somewhere in Germany other than the main theatre of operations, in Italy, or in garrisons elsewhere. French and Italian forces in Italy under Eugène totalled 3 corps, 2 French and 1 Italian, of which the former contained 2 divisions of 11 or 12 battalions each. The Italian corps infantry comprised 2 divisions, as well as 3 battalions of the Italian Guard in reserve. At the smaller structural level, Napoleon increased the number of line and light infantry regiments by another 22 by incorporating National Guard (Garde Nationale) cohorts and drafting in 6 regiments of sailors. All regiments now contained 4 battalions, each averaging about 500 men strong. After the disastrous Battle of Leipzig in October, Napoleon’s army retreated to the Rhine. With the defection of practically all his allies, his forces then consisted almost exclusively of French troops, whose numbers and quality were bolstered by drawing heavily upon veteran forces from Spain and the call-up of ever younger recruits for the defence of home soil. In terms exclusively of regular infantry, at the end of the year the army contained six corps, all understrength and exhausted.

For the campaign of 1814 the order of battle changed regularly, with the composition of line units varying greatly as new conscripts were added to existing units and ad hoc formations composed of National Guards and other elements bolstered numbers. In the main theatre of operations east of Paris (as opposed to those operating against Wellington in the south), the Emperor could still deploy five infantry corps in February, when the fighting began, plus several reserve divisions of the National Guard. Most regiments contained only one or two battalions, usually far below regulation strength and containing a high proportion of green troops. Quite apart from Napoleon’s immediate forces in eastern France, Soult maintained a force of six infantry divisions around Bayonne, in the south of the country. Eugène continued to maintain a force in Italy in 1814, while Augereau led five infantry divisions at Lyons. General Maison had a small corps in Holland and Suchet still commanded more than 30,000 infantry in Catalonia. When the Allies reached Paris and Napoleon abdicated, the French Army still contained, at least in theory, 130 regiments of the line and 32 of leégeère.

For the Waterloo campaign in 1815 the army had at its disposal — though it could not deploy all of these for operations in Belgium owing to other commitments, particular frontier defence — ninety regiments of line infantry and fifteen of light. Most regiments contained two battalions, though some had three. Line regiments were numbered up to 111, but with some of these lying vacant. Leégeère regiments were numbered 1 to 15. No foreign units served in the campaign apart from the 2nd Swiss. Napoleon deployed five infantry corps in Belgium. I and II Corps, under d’Erlon and Reille, respectively, each contained 4 infantry divisions, each of 2 brigades, each of 2 line or light infantry regiments or a combination of both. III, IV and VI Corps contained only 3 infantry divisions each, but in other respects resembled the organisation of I and II Corps, i.e. 2 brigades per division, each of 2 regiments. Altogether, about 77,400 infantry (including that of the Imperial Guard) fought on 18 June: 53,400 at Waterloo and 24,000 at Wavre.

CAVALRY

Heavy cavalry consisted of cuirassiers and carabiniers, of which both were almost always consolidated to form a cavalry reserve. The former were mounted on large, heavy set horses with the purpose of performing the charge in battle, taking advantage of their size for the sake of shock action. Officers and troops wore the metal cuirass, which protected their chest and back, as well as a helmet. Carabiniers, also mounted on heavy horses, were the elite form of cuirassiers, starting their existence with only a breastplate, but after 1809 acquiring a double cuirass.

Light cavalry consisted of hussars, chasseurs à cheval, chevau-leégers (later chevau-leéger-lanciers) and dragoons, the last of which actually qualified as medium cavalry. Hussars were elite light cavalry modelled on Hungarian units which had shown particular skill in raiding and skirmishing during the campaigns against Frederick the Great in the mid-eighteenth century. The chasseurs, the mounted equivalent of the light infantry, constituted the standard form of lightly mounted troops and were the most numerous form of cavalry. The chevau-leégers performed the same function as chasseurs, but in 1810 were converted into lancers. Four years later a similar type of unit, the Eclaireurs (Scouts) and Gardes d’honneur, had a brief existence. Dragoons could perform a dual function, fighting mounted or on foot; indeed, they began their existence, long before the Napoleonic Wars, as mounted infantry who employed horses for speed of movement. By the Austerlitz campaign, however, nearly all dragoons served in a mounted role and seldom fought on foot.

Cavalry regiments were led by a colonel, with a second-in-command holding the rank of major, who carried out administrative functions. From 1801 each cavalry regiment had an elite company which always stood on the right end of the line as the cavalry’s counterpart of the grenadier company in the infantry. The elite company served as the senior company of the two in the 1st Squadron. From Septemb...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter One - The French Army

- Chapter Two - The Russian Army

- Chapter Three - The Austrian Army

- Chapter Four - The Prussian Army

- Chapter Five - The British Army

- Chapter Six - The Armies of the Confederation of the Rhine

- Chapter Seven - The Spanish Army

- Chapter Eight - The Portuguese Army

- Chapter Nine - The Army of the Duchy of Warsaw

- Chapter Ten - The Army of the Kingdom of Italy

- Further Reading

- Index