- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

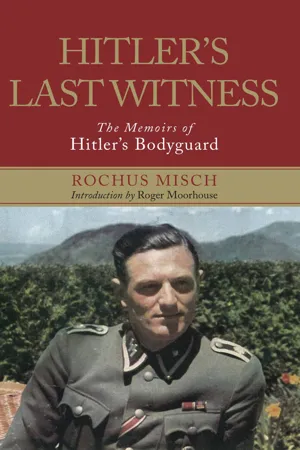

This memoir of Hitler's personal bodyguard presents "convincing first-person testimony of the dictator's final desperate months, days and hours" (

Huffington Post).

After being seriously wounded in the 1939 Polish campaign, Rochus Misch was invited to join Hitler's SS-bodyguard. There he served until the war's end as Hitler's bodyguard, courier, orderly, and, finally, as Chief of Communications.

On the Berghoff terrace, he watched Eva Braun organize parties, observed Heinrich Himmler and Albert Speer, and monitored telephone conversations from Berlin to the East Prussian Headquarters on July 20, 1944—after the attempt on Hitler's life. As the Allied forces closed in, Misch was drawn into the Führerbunker with the last of the faithful. He remained in charge of the bunker switchboard as his duty required, even after Hitler committed suicide.

Misch knew Hitler the private man. His memoirs offer an intimate view of life in close attendance to Hitler and of the endless hours deep inside the bunker. They also provide new insights into military events—such as Hitler's initial feeling that the 6th Army should pull out of Stalingrad. Shortly before he died, Misch wrote a new introduction for this English-language edition.

After being seriously wounded in the 1939 Polish campaign, Rochus Misch was invited to join Hitler's SS-bodyguard. There he served until the war's end as Hitler's bodyguard, courier, orderly, and, finally, as Chief of Communications.

On the Berghoff terrace, he watched Eva Braun organize parties, observed Heinrich Himmler and Albert Speer, and monitored telephone conversations from Berlin to the East Prussian Headquarters on July 20, 1944—after the attempt on Hitler's life. As the Allied forces closed in, Misch was drawn into the Führerbunker with the last of the faithful. He remained in charge of the bunker switchboard as his duty required, even after Hitler committed suicide.

Misch knew Hitler the private man. His memoirs offer an intimate view of life in close attendance to Hitler and of the endless hours deep inside the bunker. They also provide new insights into military events—such as Hitler's initial feeling that the 6th Army should pull out of Stalingrad. Shortly before he died, Misch wrote a new introduction for this English-language edition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hitler's Last Witness by Rochus Misch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

My Childhood: 1917–1937

‘But he thanked God for allowing him to experience all kinds of misfortune, and spent five whole years in the dungeon.’

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, ‘Sankt-Rochus-Fest zu Bingen’ (The Orphan Boy from the Village)

THE VENERABLE SANKT ROCHUS is honoured in Europe as a curer of the plague. Born in Montpellier in the thirteenth century, he had the gift of protecting people against epidemics. On 16 August 1814, Goethe attended the dedication of the Rochus Chapel at Bingen on the Rhine, in honour of the saint, and in his essay ‘Sankt-Rochus-Fest zu Bingen’ he described his impressions of that day. The name Rochus itself comes from the Old High German word rohon (roar) or from the Yiddish terms rochus and rauches (annoyance, anger), and the French rouge (red). As it so happens, the venerable Rochus was born with a red cross on his chest – a sign of his divine selection.

I found all this out a long time ago when I developed an interest in my uncommon Christian name. Whether my mother knew the story when she named me I have no idea. Equally, I do not know if my grandparents intentionally chose the plague-healer as patron of their son, my father. Rochus was my father’s name, and it was also mine. Probably I would not have been given it had my father survived my birth. After my elder brother Bruno, I am the second son of Rochus and Victoria Misch, and had my father wished to pass on his name he would surely have given it to his first-born son. However, my mother wanted me to have the name of her dead husband.

My father was a builder, while my mother Victoria worked for the Berlin public transport. Bruno was born when my parents lived on the Händelplatz, Berlin-Steglitz, but shortly afterwards, when the First World War began, the family moved to Alt-Schalkowitz1 near Oppeln in Upper Silesia. My mother’s parents lived there. I assume she did not want to spend the war alone in Berlin, as my father was quickly sent to the front.

In July 1917 my mother was very advanced in her pregnancy with me. My father was in a field hospital at Oppeln. He had been returned from the front seriously wounded, shot through a lung and missing his thumbs. Shortly before the expected date for my birth, he was allowed to leave hospital. He therefore went home, where everybody was awaiting my arrival. One night, my father suddenly had a haemorrhage and died next morning. The undertakers came to fetch him, and my mother wept and shouted as they carried the coffin past her. The midwife was already in the house and stood by helplessly. A few hours later, on that 29 July 1917 I was born.

When I was two and a half, my mother died of pneumonia following influenza. My brother Bruno met with a fatal bathing accident on 2 May 1922. His right side was stiff, probably as the result of a stroke brought on by the ice-cold water in our small brook. It took fourteen days for him to die.

Now I was quite alone with my grandparents. I was still too young to understand that I had lost my whole family within the first five years of my life: father, mother, brother. My grandparents Fronia, my mother’s parents, spoke little of their daughter. They did not even have a photograph of her hanging somewhere. So I grew up without even having a picture of my parents. Nevertheless – or perhaps because of that – I did not consciously miss my father and mother. At first, my grandmother was my guardian. Later, in the 1930s, when she was too old for it, the duty was transferred to my mother’s sister, my Aunt Sofia Fronia in Berlin.

Despite this tragic start in life, I have only good memories of my childhood. However, I must have been very ill once as a small boy. I was told I had had the English Disease.2 I remember that I was taken to a special hospital in the Altvatergebirge mountains for treatment, but I do not know how I got there and how long I stayed. Apparently, they knew how to treat it.

After eight years of elementary school, my grandfather wanted me to learn a trade. He would tell me interesting stories, and in Berlin he had worked on the building of the Teltow canal. This was a big project, which had opened in 1906 – no fewer than 10,000 men had worked on it. It was very important for him that one did something ‘with one’s hands’, develop one’s talent for something. Thus, he got me to learn the mandolin. The master tailor in the village taught me this instrument.

I well remember my grandfather having a big row with the school director Demski, when he took me out of school. The director was adamant that I should continue my education and go to a higher school in Oppeln – I had good grades. However, grandfather had decided against it, even though the director visited us at home in an effort to convince him. To no avail. It was obvious to my grandfather that I should learn a trade. To his great joy, I had an ‘A’ in Art, and so it was quickly decided that I should be a painter. Grandfather would brook no opposition, being a thorough-going Prussian authoritarian, but in any case I had no objections.

My cousin Marie from Hoyerswerda, who happened to be visiting us when my grandfather had this row with the school director, obtained for me in 1932 through her husband’s contacts an apprenticeship with the firm Schüller and Model. During the first two years, I lived with my instructor Schüller. He also had a son, Gerhard. My instructor was a kind of foster-father to me, but ultimately I was left to my own devices, although I was not given a key to the house. If nobody was home, I had to wait somewhere. This was not too bad – I was a loner and could always find something to do.

I had great fun as an apprentice. I may say that I was specially gifted, and from early on I was given many interesting things to do. We painted cinema placards and gigantic advertisements on walls. For example ‘Persil – for all your washing only Persil’ stood in letters as tall as a man at a neighbouring station, the name of which I can no longer recall.

When Hitler became Reich chancellor in 1933 hardly anybody in Hoyerswerda was interested. There must have been some sort of event on the marketplace, but if there was I never noticed; at the time, the name Adolf Hitler meant next to nothing to me. Hoyerswerda, a small town, was rather left-wing because of its many mine workers. Even the Schüller family had nothing to do with the National Socialists. The boys of my other boss, Herr Model, however, were in a Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten3 (National Political Education Institute; ‘Napola’ for short); and a neighbour’s son joined the Hitler Youth, but all that passed me by. Subsequently, I never observed any oppression, arrests or other measures against people, which could be traced back to the new regime.

In 1935, the year before the Berlin Olympic Games, Schüller and Model received an especially important commission from the local shooting club: at every festival a painting would be prepared as a prize, and this time the theme had to be the Olympic Games. Our talented master Schrämmer wanted to paint it, but scarcely had he begun than he fell seriously ill. Therefore, at just eighteen years of age and not yet even a journeyman, I was chosen to finish it. It was actually two pictures: one as a prize for the victor in the main competition, and one for the junior champion. The first work showed the Olympic stadium; the other was of a torch bearer, with the countries through which he would run, in the background.

I received 300 Reichsmarks for the big painting, and 190 Reichsmarks for the smaller one. I was rich. This was really a lot of money. My instructor contacted my grandparents in order to make sure I did something sensible with it. My continued training was considered a good investment by both my grandfather and my instructor.

Therefore, for six months I was able to attend the Masters’ School for Fine Arts in Cologne. Note, this was as a trainee. As I was not a journeyman, naturally I could not become a master even though I had passed all my examinations. There were about forty master-instructors at the school from all regions of the German Reich. I learned many interesting creative techniques, such as gilding and varnishing processes, also stage design and much more. I went about the job with a will.

When our school was commissioned to design a set for a Cologne theatre in the cathedral office, I noticed that the stage manager cast frequent looks at my work. One day he asked if I would like to be an extra in a play about the building of the cathedral, as a stone-cutter, because it would be better if the actor already had the movements for the part. At first, I was not particularly enthusiastic. I did not see myself on the stage. After some hesitation, I let myself be persuaded. Thus, I became a thirteenth-century stone-cutter with a boy’s head and leather apron forced to do compulsory labour on the cathedral building. It was a speaking role, in which I had to say: ‘Maria’. Although I liked acting in the end, without doubt I preferred the five Reichsmarks, which I received per performance, more. One day in the future I would have to do forced labour for real: as a POW in Russian work camps, I painted shields for building sites. This macabre parallel is only one of the many strange things that Fate had in store for me.

In Cologne I lodged at the Kolpinghaus youth hostel on Breite-Strasse. One could live very comfortably there, and a meal was to be bought for only forty pfennigs. At the beginning of March 1936, I saw German soldiers on the Cologne streets, moving out to occupy the demilitarised Rhineland. At the time, this was not a special experience for me. It was during the famed Cologne carnival, and the city was in a state of high excitement – just as it used to be in its ‘wild days’. There was music and dancing everywhere. I was fascinated by the great city, the legendary gaiety of the Rhine and naturally the girls of Cologne. I felt free and had a lot of fun. After this six-month excursion I went back to Hoyerswerda to continue my training.

I was soon able to put to good use what I had learnt in my advanced training. In the whole town I was now the only person who could gild competently. Most people thought it was dreadfully expensive, but it never was. I knew that one could go a very long way with a bag of gold dust for thirty-seven Reichsmarks. In Cologne I had learnt that, with a little pile of gold dust sufficient to cover a five-mark coin, I could gild a whole horse. When they wanted to use bronze for the clock on an evangelical church tower at Hoyerswerda, I made it clear that the bronze would soon darken. Thanks to my skill in persuasion they used gold instead. And so I gilded not only this clock, but also the background of the fourteen stations of the cross in a Catholic church. At Moritzburg Castle near Dresden, Schüller and Model restored the gilded picture frames. The remains of the gold I preserved carefully in silk paper. A short while ago, I gave away my last packet of it.

Olympic Games: 1936

In the spring of 1936, at the shooting festival for which I had done the painting in 1935, I took part in the actual rifle competition. I was the third-best Silesian in the youth competition, for which I received a small bronze medal with the official Olympic logo and the inscription: ‘We call the Youth of the World – Berlin 1936’, a diploma and a free ticket for the opening day of the Berlin Olympic Games.

Thus, on 1 August 1936, there I stood, the young man from the village with my Aunt Sofia in the crowd before the Reich stadium. The tension, the masses of people, the theatre – it was tremendous.

The entry of Hitler made the greatest impact on me. As luck would have it, just at the very moment that my aunt and I stood very close to the carriageway for the guests of honour, Hitler came past, at the head of the triumphal convoy of officials and guests of honour, which had driven from the Reich Chancellery through Berlin. He stood up in the open limousine saluting the crowd, surrounded by members of his personal bodyguard, who rounded off the picture perfectly in their black uniforms with white belts. The crowd was beside itself. Everybody was now looking in one direction, all eyes were on this man. Not ten metres away from us, the limousine slowed. Before it came to a stop, the men of the bodyguard party had jumped off the running boards elegantly and threw their whole weight into holding back the surging throng of spectators. The public pushed and shoved. Whoever managed to get through the cordon clung to the vehicle like a drunkard and had to be dragged away. All was jubilation and cries of joy – it was deafening.

I was completely swept up in the emotion; tears welled up in my eyes. ‘What is wrong with you?’ my aunt asked. I was dreaming, imagining myself standing on the running board of the car, a member of the bodyguard squad, in one of those smart uniforms. Man, they were just normal soldiers, how lucky they were. I never considered that my daydream would one day become reality.

My ticket allowed me to go much further into the Olympic stadium, but I did not use it. After experiencing the entry of Hitler at such close quarters, I was so full of impressions that all I wanted to do was return home. Go any further into this frenzy? No, I was not in a state to do so. It was simply too much for me. And, anyway, my aunt could not have got in without a ticket. Never again did I experience anything comparable to this spectacle. Berlin sank into a sea of flags. One could hardly make headway through the streets.

For days and weeks after that event I was still totally gripped if I thought back to it. The overwhelming entry of Hitler had not brought me nearer to the Nazis and their policies. What they wanted, to where they were moving our country, who did what within the regime – people talked about it but I never took part in these discussions. I was interested in my work, and besides that only sport. I loved playing football, which my boss at work did not look upon kindly, for fear that I might be injured. After watching me play once, however, he relented. Apparently, he was a little proud of his apprentice, for in contrast to his son I was a really gifted footballer.

In December 1936, my apprenticeship terminated. My journeyman piece, some advertising for a travel company, was never finished. Scarcely had I started on it than my boss told me to leave it. ‘The others are no match for you, Rochus.’ My practical work was therefore waived; I received only the highest marks.

After some time as an assistant painter at Hoyerswerda, one of the older colleagues at Schüller and Model, the master-painter (arts) Schweizer from Hornberg in the Black Forest, brought me to his home town, where he wanted to set up his own business. He was hoping to receive commissions under a programme aiming at beautifying Germany, which attracted state subsidies of up to forty-five per cent. Therefore, I completed designs for public buildings in Hornberg, Triberg and Hausach, three pieces each, and then the public commissions really began to roll in. We also painted advertising boards, among others for an important exhibition in Brussels. I earned ninety-five pfennigs an hour.

In the Black Forest, I quickly made friends, and in my spare time I was mostly with three or four people of my own age. One of them was a technical draughtsman in a neighbouring business. We often went to a rustic inn, offering glorious Black Forest ham. Before our eyes, breath-fine slices were cut from a giant ham with a very sharp knife, and we relished them with black bread and mustard. We went a lot to dances and the swimming baths. There, I got to know a miller’s two daughters and tried to impress them with my virtuosity on the mandolin. One of them became my first girlfriend. Best of all, I liked going with my friends to Überlingen at Lake Constance at the weekends. I packed the mandolin and bathing trunks, and then off we went. The best memories of my youth are from this time.

Of course, we got up to all kinds of mischief. We boys were able to roam freely and unsupervised – the opportunity had to be seized. Once, in Überlingen, we came across a defective cigarette machine, which simply could not stop spilling out cigarettes. ‘Try to leave some behind,’ my friend warned me – his pockets already stuffed full with packets of them.

None of us knew then, of course, that the carefree times for our generation, as for so many others, would soon come to an abrupt end.

Chapter 2

Conscripted Soldier: 1937–1939

IN 1937 I RECEIVED my call-up notice. I had to become a soldier. There was no choice.

A few weeks after my twentieth birthday I took the train to Offenburg, together with my friend of the same age, Hermann, for assessment. SS men had set up a small table in the open and were pressing fairly hard for volunteers to do their national service with the Verfügungstruppe.1 The lure was four years’ military training while avoiding the compulsory RAD (Reichs Arbeits Dienst/Reich Work Service). It counted as full discharge of the general obligation and could provide direct entry into state service.

For my friend Hermann ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Also by Frontline Books

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction by Roger Moorhouse

- Author’s Introduction

- 1 My Childhood: 1917–1937

- 2 Conscripted Soldier: 1937–1939

- 3 The Outbreak of War: 1939

- 4 Hitler Needs a Courier

- 5 My Reich – The Telephone Switchboard

- 6 The Berghof, Hitler’s Special Train and Rudolf Hess

- 7 FHQ Wolfsschanze: 1941

- 8 FHQ Wolfsschanze, FHQ Wehrwolf, Stalingrad My Honeymoon: 1942

- 9 The Eastern Front Begins to Turn West

- 10 The Philanderer: 1944

- 11 Weddings and Treason: 1944

- 12 Preparing the Berlin Bunker: February–April 1945

- 13 Bunker Life: The Last Fortnight of April 1945

- 14 Hitler’s Last Day: 30 April 1945

- 15 Negotiations and the Goebbels’s Children: 1 May 1945

- 16 Break-out and Capture

- 17 My Nine Years in Soviet Captivity

- 18 My Homecoming and New Beginnings

- Short Biographies

- Notes