- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"This superb book . . . will undoubtedly become the definitive volume on British Aircraft carriers and naval aviation . . . magnificent."—Marine News

This book is a meticulously detailed history of British aircraft-carrying ships from the earliest experimental vessels to the Queen Elizabeth class, currently under construction and the largest ships ever built for the Royal Navy. Individual chapters cover the design and construction of each class, with full technical details, and there are extensive summaries of every ship's career. Apart from the obvious large-deck carriers, the book also includes seaplane carriers, escort carriers and MAC ships, the maintenance ships built on carrier hulls, unbuilt projects, and the modern LPH. It concludes with a look at the future of naval aviation, while numerous appendices summarize related subjects like naval aircraft, recognition markings and the circumstances surrounding the loss of every British carrier. As befits such an important reference work, it is heavily illustrated with a magnificent gallery of photos and plans, including the first publication of original plans in full color, one on a magnificent gatefold.

Written by the leading historian of British carrier aviation, himself a retired Fleet Air Arm pilot, it displays the authority of a lifetime's research combined with a practical understanding of the issues surrounding the design and operation of aircraft carriers. As such British Aircraft Carriers is certain to become the standard work on the subject.

"An outstanding highly informative reference work. It is a masterpiece which should be on every naval person's bookshelf. It is a pleasure to read and a pleasure to own."—Australian Naval Institute

This book is a meticulously detailed history of British aircraft-carrying ships from the earliest experimental vessels to the Queen Elizabeth class, currently under construction and the largest ships ever built for the Royal Navy. Individual chapters cover the design and construction of each class, with full technical details, and there are extensive summaries of every ship's career. Apart from the obvious large-deck carriers, the book also includes seaplane carriers, escort carriers and MAC ships, the maintenance ships built on carrier hulls, unbuilt projects, and the modern LPH. It concludes with a look at the future of naval aviation, while numerous appendices summarize related subjects like naval aircraft, recognition markings and the circumstances surrounding the loss of every British carrier. As befits such an important reference work, it is heavily illustrated with a magnificent gallery of photos and plans, including the first publication of original plans in full color, one on a magnificent gatefold.

Written by the leading historian of British carrier aviation, himself a retired Fleet Air Arm pilot, it displays the authority of a lifetime's research combined with a practical understanding of the issues surrounding the design and operation of aircraft carriers. As such British Aircraft Carriers is certain to become the standard work on the subject.

"An outstanding highly informative reference work. It is a masterpiece which should be on every naval person's bookshelf. It is a pleasure to read and a pleasure to own."—Australian Naval Institute

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access British Aircraft Carriers by David Hobbs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

ADMIRALTY INTEREST IN AVIATION 1908-1911

The Admiralty’s interest in aviation followed an approach to new technology that had proved successful in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. It was based on evaluation, the study of what other nations and potential enemies were doing, and the certainty that British industry would build new equipment faster and in greater quantity than the competition once a decision to proceed had been taken. New weapons had evolved over such short timescales that the same dynamic personalities were involved with the introduction of torpedoes, submarines, aircraft and the modifications that needed to be made to warships in order to deploy or support them. Although man’s first powered flights in a heavier-than-air machine are generally accepted to have been achieved by the Wright Brothers in the USA on 17 December 1903, the first powered flight in Britain did not occur until 16 October 1908, when American Samuel Franklin Cowdery (‘Colonel Cody’) made a flight of 1,390ft at Farnborough, Hampshire, in British Army Aeroplane No. 1. There was little prospect of these early machines operating from a warship to achieve any practical naval purpose, or of operating in support of the fleet from an air station ashore, so it was hardly surprising that when the Wright Brothers offered their patents to the Admiralty in 1907, they had been politely refused. Balloons had been flying for over a hundred years, however, and the scientific establishment regarded motor-powered airships with their greater endurance and load-carrying capability as having more potential for naval operations than the underpowered heavier-than-air aircraft that began to emerge after 1908. In Germany Count Zeppelin had achieved some success with his prototype rigid airships, although the majority had crashed or otherwise demonstrated unreliability that prevented the German Navy from ordering its own prototype. It was accepted that the design of practical aeroplanes depended on the development of engines of higher power and less weight. The Admiralty maintained close touch with progress in what was widely regarded as an eccentric gentleman’s sport through studying the reports of naval officers who taught themselves to fly and, in some cases, designed their own aircraft, and by sending representatives to aviation meetings and conferences. The latter focused on what was then referred to as ‘aerial navigation’ and were held in France, the contemporary hub of aircraft and engine development.

In September 1909 Lieutenants Porte and Pirie RN, both serving in submarines and based at Fort Blockhouse, Gosport, designed and built a biplane glider. They hauled it on a specially designed trolley to the top of Portsdown Hill, overlooking Portsmouth, with the help of a number of sailors and attempted to take off in it. A wooden trackway was laid down on the grass slope and the trolley, with the aircraft on top, ran down it using gravity to accelerate until sufficient speed was reached to lift off. In common with current submarine practice, the aircraft had two pilots or coxswains, one controlling up/down movement and the other left/right. Their combined weight proved too much; their co-ordination was unlikely to be perfect on this first flight and the machine crashed. Had it flown successfully, the next planned step was to fit a JAP engine and attempt prolonged, powered flight. The Admiralty was aware of the experiment and had sanctioned the use of sailors and material to support it, but refused to cover all the enthusiastic young officers’ costs as the flight had proved to be a failure. Had it succeeded things might have moved forward in a different way.

The French Navy was the first to set up an investigative commission to establish the Service’s aeronautical requirements, and Admiral Le Pord was charged with deciding whether airships or heavier-than-air aircraft were better suited to naval operations. In the summer of 1910 he recommended in favour of the latter, especially seaplanes, in a far-sighted report that recommended the conversion of a warship to support seaplane operations. His findings were reinforced in the autumn of 1910 when Henri Fabre became the first pilot take-off from and alight on the water, using a seaplane he had designed himself. The navy chose the destroyer depot ship Foudre, which already had extensive workshops, booms capable of raising and lowering seaplanes and useful clear deck space for aircraft to be prepared for flight. A canvas hangar was later replaced by a fixed metal structure and it was the first ship in any navy to be modified for the operation of aircraft.

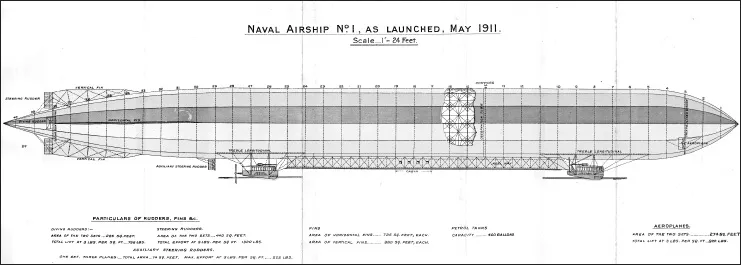

HM Rigid Airship Number 1 (R1) as designed. The lines drawn against the bottom of the cars show where the water level was to be when she floated while moored to the cruiser Hermione for replenishment and a crew change. She was painted silver on top to reflect sunlight and prevent it from causing excessive heat which would expand the gas in the seventeen internal gas bags, and yellow underneath so that she could be seen and identified by warships. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

In the USA, Captain Washington I Chambers of the US Navy (USN) secured funding to demonstrate the ability of aircraft to take-off from and to land on temporary wooden platforms rigged on cruisers, and the ability of such ships to hoist seaplanes in and out. On 14 November 1910 Eugene Ely, a demonstration pilot working for the Glenn Curtiss Aeroplane Company, successfully took off from a platform rigged over the forecastle of the USS Birmingham. Later, on 18 January 1911, he landed the same aeroplane on a larger platform built over the quarterdeck of the USS Pennsylvania and then took off again. On 17 February Glenn Curtiss himself became the second man to operate from the water when he made a very brief hop in his poorly balanced Tractor Hydro biplane to Pennsylvania, landed near the ship, was hoisted in by the boat crane and then hoisted out again for Curtiss to taxi back to the Curtiss shore-side camp. The demonstrations showed sufficient future promise for the USN to agree to the training of its first pilot by Curtiss. They also proved to be the catalyst that led the Royal Navy (RN) to set up its own formalised pilot training scheme at Eastchurch, Kent, later in 1911.

There were visionaries who wrote of the potential capability that fully-developed heavier-than-air aircraft could bring to naval warfare, among them Victor Loughheed (half brother of the two men who founded the Lockheed Corporation, using a revised spelling of the family name) in the USA and Clement Ader in France. In 1909 Loughheed described ‘great, unarmoured, linerlike hulls designed with clear and level decks’ for aircraft to launch from, provided with storage rooms for ‘fuel, repair facilities and explosives’ capable of destroying fleets of conventional ships operated by navies ‘that refused to profit by the lessons of progress’. At about the same time Clement Ader wrote in a second edition of his book L’Aviation Militaire about a ship with a flight deck that must be ‘as wide as possible, long, flat and unobstructed, not conforming to the lines of the hull for aircraft to take-off and land’. He went a step further than Loughheed, predicting that ‘servicing the aircraft would have to be done below this deck with access by means of a lift long enough and wide enough to take an aircraft with its wings folded’. Workshops would run along either side of this maintenance area. Although both descriptions were regarded as futuristic in 1910, both authors might have been surprised if they could have seen how close their ideas actually were to fulfilment.

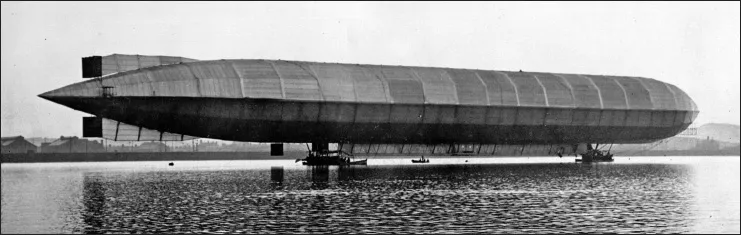

R1 is moved out to her mooring tower in Devonshire Basin, Barrow-in-Furness, in May 1911. Most of her weight is taken by the inflated gas bags, but her cars are resting on the surface. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

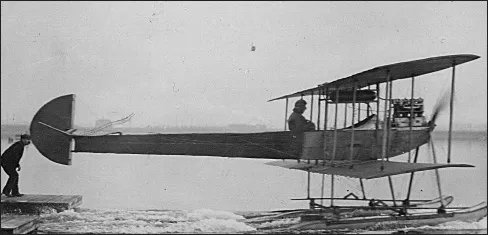

Commander Schwann taxies his Avro biplane on Devonshire Basin, Barrow-in-Furness, during 1911.

In 1911, although Captain Chambers’s demonstrations had shown the technique to be possible, the RN was not yet convinced that takeoff and landing from a ship by aircraft fitted with wheeled undercarriages represented the ideal solution. In the 1911/12 edition of The Navy League Annual it was stated in a chapter by Frank W B Hambling headed ‘The Aeroplane in Naval Warfare’ that ‘a little common sense would indicate that the type necessary is one capable of acting with and from our Navy, of resting on and rising from the water. Its advantages for the work we require our scouts to perform are manifold. It could use a ship as a base, without requiring the erection of a special deck-landing platform; any number of aeroplanes could be accommodated in one vessel; it could, while resting on the water recharge fuel tanks and effect minor repairs, save fuel, rest its pilot and engine. … in the event of a forced landing, it would always be at home. These are some of the advantages not possessed by the ordinary type.’ Practical experience with seaplanes, as they became known, was to show them in a less favourable light, but the article illustrates contemporary naval thinking. Although his article did not say so specifically, Hambling clearly expected that ships intended to support aircraft operations would be moored in sheltered waters, lowering their aircraft into the water before takeoff and recovering them after landing. Operation from the rough seas of the open ocean had yet to be demonstrated, and only a handful of landings in sheltered waters had been performed. The internal volume of a merchant ship would obviously be useful for the stowage of aircraft and spares, but the speed to operate with the battle fleet and the bulky machinery needed to achieve it were not, initially, considered important.

From February 1911 the officers standing by HM Airship R1 at Barrow-in-Furness studied the possibility of operating aircraft from ships. They took out a number of patents on devices ranging from catapults to quick-release hooks for use lowering seaplanes on to the water. Commander Schwann RN raised the money to purchase an Avro biplane which was fitted with a variety of floats, each of them an incremental improvement in design and constructed by sailors standing by R1 while it was under construction; they were made from the same type of duralumin used for the airship’s frames. After a succession of taxying trials in Cavendish Dock, Schwann, who had not yet qualified as a pilot, became the first British aviator to take-off from water in November 1911. Unfortunately he crashed on landing, but a few weeks later Lieutenant A M Longmore RN, by then qualified as a pilot, landed Short S.38 naval biplane number 2 on floats on the River Medway. By 1912 naval aviation’s practical steps forward were beginning to catch up with the theory.

The Clydeside shipbuilding firm of William Beardmore took theory a step further in 1912 when they proposed the construction of an ‘aircraft parent ship’ to the Admiralty. It was clearly intended to be a mobile base which would anchor in coastal waters rather than operate as a part of the battle fleet. It featured a long through-deck with workshops and hangarage on either side of it connected, over the deck, by a bridge from which both ship navigation and flying operations would have been controlled. The through-deck was level and ran for the full length of the hull, intended to allow convenient access for the aircraft between the hangars, workshops and working decks. In calm conditions, take-off into wind from the deck forward of the flying bridge might have been possible, but any attempt to land on the after deck, into the turbulence caused by the bridge structure and funnel gasses, would have been extremely hazardous. Booms would have been used to move aircraft from the deck into the water for flight and to recover them after landing. Wireless telegraphy (W/T) aerials fitted to tall masts would have allowed long-range communications commensurate with Admiral Fisher’s concept of a ‘Flying Squadron’ of reconnaissance vessels and battlecruisers able to deploy to considerable distances from the UK to seek out an enemy force and destroy it. Rather broad in the beam, it would not have been a fast ship, and coal-fired boilers would have produced copious amounts of smoke and soot. With no experience of heavier-than-air aircraft operations, the Admiralty decided against placing order for such an experimental ship, but it provides an interesting starting point for the study of British aircraft carrier design.

The cruiser Hermione before her conversion into an airship support vessel. (A D BAKER III)

The Royal Navy’s first practical steps towards developing naval aviation began in 1908, when the Director of Naval Ordnance, Captain R H S Bacon RN, was sent to France to report on the first international aviation meeting at Reims, effectively an international ‘showcase’ for aircraft development. After his return he forwarded a paper to the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, on 21 July 1908 in which he recommended the appointment of a Naval Air Assistant within the naval staff at the Admiralty; consultations with the War Office over the design and use of airships and the construction of a rigid airship for the Navy by Vickers, Sons and Maxim at Barrow-in-Furness. Within a remarkably short period of weeks the latter proposal was endorsed by the Committee of Imperial Defence and the RN entered the ‘air age’ when the sum of £35,000 was included in the 1909-10 Naval Estimates for the construction of a rigid airship. This was the same unit price as the submarines being built for the Admiralty by Vickers under an exclusive contract at the time. Bacon was one of the group of innovative officers who supported Admiral Fisher’s reforms and who were known as the ‘Fishpond’. After his appointment in charge of the embryo Submarine Branch, Bacon was the first captain of the revolutionary new battleship Dreadnought and then Director of Naval Ordnance, in charge of the Admiralty Directorate responsible for the development and introduction of new weapons. As the first Inspecting Captain of Submarines, Bacon had worked closely with Vickers and the firm clearly wanted to expand its portfolio into the new technology, and proposed another exclusive contract for the anticipated production of airships for the Royal Navy. As an inducement the firm built an airship construction shed in Cavendish Dock at Barrow-in-Furness at its own expense and agreed to cover the additional cost if construction of Rigid Airship number 1 exceeded the £35,000 allocated. In the twenty-first century their proposal would be known as a ‘private finance initiative’ with the catch in the eventual inflated price that the taxpayer would have to pay for the exclusive deal.

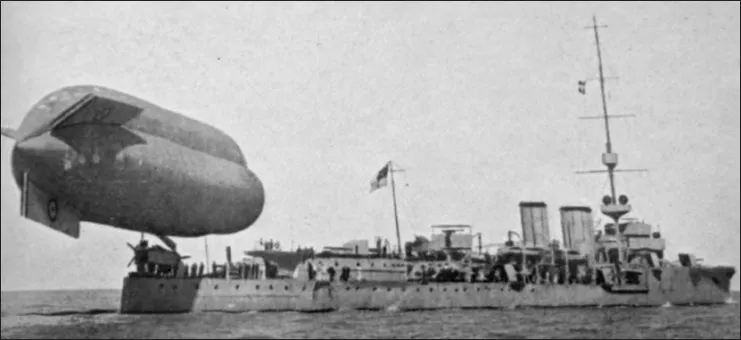

Some idea of how Hermione would have appeared operating as an airship support vessel can be gained from this later photograph of a cruiser refuelling a non-rigid airship. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The R1 was the largest aircraft of its day and the first to have a structure made of duralumin. It successfully rode out a gale while tethered to a mast in Cavendish Dock during trials in May 1911, but it was too heavy to begin flying trials and had to be substantially lightened before they could be attempted. A number of structural alterations were made, but the airship was damaged while being pulled out of its shed in September 1911 and subsequently scrapped. It had a number of distinctly naval features, including an anchor and cable, a sea-boat that could be lowered into the water from a low hover and two wooden control/power cars which would allow the airship to float on the water if necessary. It also had a telephone exchange to connect the two control cars, the navigation position on top of the hull, the crew’s quarters and the first wireless transmitter ever to be fitted in an aircraft; a prototype device designed especially for this application by the Admiralty Signals Establishment. It was unusual in making no spark when transmitting in order to lessen the risk of explosion if hydrogen gas from one of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Admiralty interest in aviation 1908–1911

- Chapter 2: Early ship trials and demonstrations

- Chapter 3: Seaplane carriers

- Chapter 4: Furious and Vindictive

- Chapter 5: Argus

- Chapter 6: Eagle

- Chapter 7: Hermes

- Chapter 8: The development of carriers in other navies

- Chapter 9: Courageous class

- Chapter 10: Ark Royal

- Chapter 11: Illustrious class – first group

- Chapter 12: Indomitable

- Chapter 13: Implacable group

- Chapter 14: British-built escort carriers and MAC-ships

- Chapter 15: Archer class

- Chapter 16: Attacker class

- Chapter 17: Ruler class

- Chapter 18: Project Habbakuk

- Chapter 19: Audacious class

- Chapter 20: Colossus class

- Chapter 21: Majestic class

- Chapter 22: Malta class

- Chapter 23: A comparison with aircraft carriers in other navies COLOUR PLATES: Original plans between 224 and 225

- Chapter 24: The maintenance carriers Unicorn, Pioneer and Perseus

- Chapter 25: Hermes class

- Chapter 26: British carrierborne aircraft and their operation

- Chapter 27: Post-1945 aircraft carrier designs that were not built

- Chapter 28: The reconstruction – Victorious, Hermes and Eagle

- Chapter 29: CVA-01: the unbuilt Queen Elizabeth

- Chapter 30: Ark Royal – controversy, a single carrier and her aircraft

- Chapter 31: Small carrier designs for a future fleet

- Chapter 32: Short take-off and vertical landing

- Chapter 33: Invincible class

- Chapter 34: Ocean – landing platform (helicopter)

- Chapter 35: Queen Elizabeth class

- Chapter 36: Aircraft carriers in the Commonwealth navies

- Chapter 37: British carrier concepts and foreign aircraft carriers compared

- Chapter 38: Carrierborne aircraft in the twenty-first century

- Chapter 39: Unmanned aircraft – a fast-moving technical and tactical revolution

- Chapter 40: The Royal Navy’s future prospects: the author’s afterwords

- APPENDICES

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index