- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Final Advance, September to November 1918

About this book

This is the story the British Expeditionary Forces part in the final days of the Advance to Victory. It starts with the massive offensive against the Hindenburg Line at the end of September 1918. Second Army launched the first of the British attacks in Flanders on the 28th, followed by Fourth Army the next day along the St Quentin Canal.Both First and Third Armies joined in, breaking the Hindenburg Line across the Lys plain and the Artois region, taking Cambrai by 10 October. The narrative then follows the advance through the battles of the River Selle and the River Sambre. It culminates with the final operations, including the actions at Maubeuge and Mons, just before the Armistice on 11 November 1918. Time and again the British and Empire troops used well-rehearsed combined arms tactics to break down German resistance as the four year conflict came to an end.Each stage of the six week long battle is dealt with equally, focusing on the most talked about side of the campaign, the BEFs side. Over fifty new maps chart the day by day progress of the five armies. Together the narrative and the maps explain the British Armys experience during the days of World War One. The men who led the advances, broke down the defences and those who were awarded the Victoria Cross are mentioned. Discover the end of the Advance to Victory and learn how the British Army reached the peak of their learning curve.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Final Advance, September to November 1918 by Andrew Rawson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Insufficient to Build an Enduring Defence

After four months of fighting off German attacks, it was the turn of the Allies to make their counter-stroke. The final German attack, Operation Peace Storm (Friedensturm), had started on 15 July against the French along the Chemin des Dames, driving them across the River Aisne and then back some 30 miles to the River Marne. But Généralissime Foch had held his nerve and he encouraged General Philippe Pétain to prepare a counter-offensive with the French, Italian and British troops assembling in the area.

The attack opened on 18 July, striking the flanks of the huge German salient, and it was only a matter of days before they were falling back to the Aisne. The attack ended at the beginning of August because a new combined offensive was being planned. On 8 August, masses of tanks joined the Fourth British Army and the First French Army as they advanced side by side across the Santerre plateau, south of the River Somme. They broke through the German defences across a 30-mile-wide front, advancing up to 8 miles in places on what would be described by General Erich Ludendorff as the ‘black day of the German Army’.

Reinforcements were rushed to the area to contain the breakthrough and the Allied attack was called off after a few days so another could be launched further to the north. The next attack was made by Third Army on 21 August between Arras and Albert, where again the British troops advanced considerable distances. It was followed up by a renewal of operations astride the Somme which allowed Fourth Army to cross the 1916 battlefield in a matter of days.

The BEF’s attack widened with fresh assaults east of Arras, which pushed the Germans all the way back to the Drocourt–Quéant Line and the River Somme. Both obstacles had been broken or bypassed by early September, sparking a German withdrawal to the old British trenches in front of the Hindenburg Line. There General Max von Boehn was hoping to stall the British so that his men could upgrade the neglected defensive positions.

There had been several developments on other parts of the line. The First French Army had advanced alongside Fourth Army as far as the Hindenburg Line in front of St Quentin. The Third and Tenth French Armies had also pushed the Germans back from the Soissons salient and the shortening of the line had allowed General Pétain to pull Third Army into reserve. Even the Americans had had success, when their attack on 12 September had sparked a withdrawal from the St Mihiel salient, south-east of Verdun.

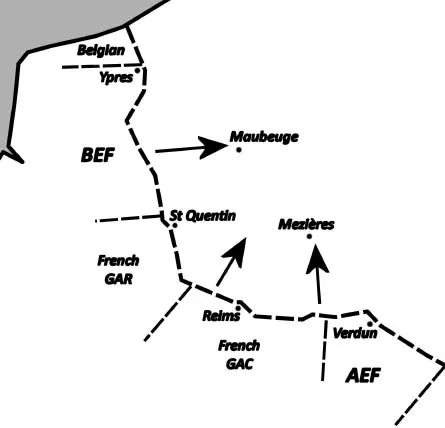

As the summer campaign progressed, thoughts for a combined autumn offensive had begun on 30 August, when Field Marshal Sir Haig suggested launching a three-pronged offensive to General John Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The northern attack would be aimed towards Cambrai and St Quentin, and it would be made by the British Expeditionary Force and the left wing of the French armies. The south attack would be made astride the River Meuse, with the right of the French armies and the AEF heading towards Mezières. The French centre would follow up by moving north between the two wings.

The Western Front in mid-September 1918, with the Allied armies poised to attack all along the line.

Three days later, Foch asked Haig and the Belgian army for their attack plans. Haig was able to report that the Germans were already retiring from the Lys salient and he expected them to go back further to release reserves to send south. On 4 September, Foch issued instructions to start planning for a new wave of attacks all along the front, starting on 20 September. Five days later he explained how he intended to confuse the German high command by hitting their line at different points over a series of days.

The first attack was to be made by French and American divisions on 26 September between Reims and the River Meuse. General John Pershing’s First American Army would breach the Hindenburg Line between the Argonne Forest and Verdun. It would advance towards the Buzancy Line, outflanking the German line opposite Fourth French Army. General Henri Gouraud’s troops would then widen the attack front to 65 miles as the French and Americans pushed north beyond the Rethel–Vouziers Line in the direction of Charleville-Mezières.

The second phase would be made by the centre of the BEF on 27 September. General Henry Horne’s First Army and General Julian Byng’s Third Army would advance side-by-side through the Hindenburg Line and push either side of Cambrai. They would then head east towards Maubeuge, forming the northern jaw of the pincer move against the flanks of the Soissons salient.

The third phase, on 28 September, would involve the Flanders Group of Armies, a combined command of Belgian, French and British troops gathered under the king of the Belgians. The attack would cover a 25-mile-wide sector, including General Herbert Plumer’s Second Army which would cross the Ypres salient to cover the BEF’s left flank.

The final strike would be made by General Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth British Army and General Marie-Eugène Debeney’s First French Army on 29 September. They would attack the Hindenburg Line either side of St Quentin and then push north-east, supporting the right flank of the BEF’s attack. This in turn would increase the pressure on the Soissons salient, so General Charles Mangin’s Tenth French Army and General Berthelot’s Fifth Army could join the advance.

Maréchal Foch wrote to Field Marshal Haig, General Pétain, General Pershing and General Jean Degoutte (the French chief of staff of the Flanders army group) on 27 September. Between them they had sixty-five divisions in reserve, ready to make a second wave of attacks or pursue the enemy. He believed that four attacks at different points on four consecutive days would confuse the German high command, so they would be unable to deploy their reserves effectively.

Foch thought the German soldier had lost confidence in his generals, after the failure to break the Allied line during the spring offensives followed by the repeated defeats during the summer. He went so far as to say they were ‘insufficient to build an enduring defence’. Meanwhile, he thought the Allied troops were full of confidence after the summer successes and he advised his generals to be ready to take up the pursuit if the German line collapsed. Everything was in the Allies’ favour but, as far as he was concerned, command and leadership were as important for winning a battle as were tactics and weapons.

The battle now depends on the determination of corps commanders and on the initiative and energy of divisional commanders. Once more, I repeat, the last say in battle comes not from the endurance of the troops alone, who never fail if appeal is made to them, but also from the impulse of the commanders.

The Meuse-Argonne Attack, 26 September

The artillery (most batteries were manned by French gunners) starting shelling positions along a 45-mile front across the Argonne at 11 pm on 25 September. General Henri Gouraud had assembled twenty-two infantry divisions and a cavalry corps in his Fourth French Army while General John Pershing had fifteen infantry divisions (which were double the size of a French or British division) and a cavalry division in the First US Army.

Both the Crown Prince and General Max von Gallwitz knew the attack was coming but there was little they could do about it. The French infantry went over the top at 5.25 am accompanied by 297 light and 29 heavy tanks. Five minutes later the Americans advanced in the Argonne Forest, assisted by 189 light French tanks.

Most of the objectives were taken on the first day, as the French and Americans fought their way through the German outpost line. However, the advance then slowed, particularly in the American sector where they were fighting through wooded terrain. Pershing had no option but to keep pushing on with his inexperienced troops, even fighting off counter-attacks made by German reinforcements. The Americans ‘were necessarily committed, generally speaking, to a direct frontal attack against strong, hostile positions fully manned by a determined enemy’. Even so, they had advanced 6 miles, taking many prisoners and heavy guns, by the time a pause was ordered on 3 October.

The line-up of the BEF’s armies in mid-September 1918. The plan was to attack in the centre, then in the north and finally in the south, to spread the German reinforcements.

Chapter 2

Ceaseless, Wearing, Unspectacular Fighting

Third Army and Fourth Army

12 to 26 September

Third Army, 12 to 26 September

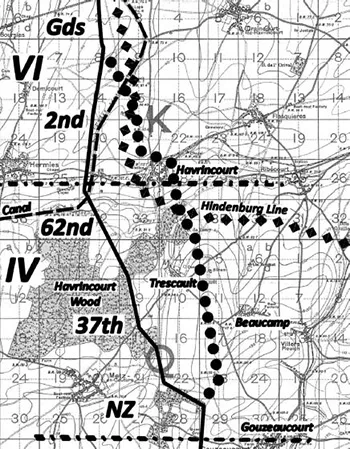

VI Corps

Guards Division, 12 September

Major General Torquhil Matheson had taken over because Major General Feilding had just returned to England. His men were busy establishing posts across the Canal du Nord. They found that the best place to cross was at Moeuvres.

52nd Division, 17 to 21 September, Moeuvres

Captain Harvie of the 1/4th KOSBs was wounded driving the Germans back from Moeuvres on 17 September but some of the 1/5th HLI were cut off. Corporal David Hunter refused to surrender and his group held out for 48 hours. He would be awarded the Victoria Cross. The 1/4th Royal Scots held onto Moeuvres during an attack on 21 September but the 1/7th Royal Scots suffered the ‘worst ordeal that they ever endured’ as their front line companies were overrun. Captain Robertson was wounded rallying the survivors but Captain Ballantyne helped them retake the lost trenches.

3rd Division, 18 September, Havrincourt

A counter-attack on 18 September threatened to drive the 2nd Royal Scots back in what was ‘no kid glove affair’. Lieutenant Colonel Henderson sent forward reinforcements to make sure the Spoil Bank, next to the Canal du Nord, was secure.

IV Corps

62nd Division, 12 September, Havrincourt Wood

Major General Robert Whigham’s division had breached the Hindenburg Line before, during the battle of Cambrai, and ‘the success of the previous year was debated with fresh interest.’ But there were no tanks this time and careful timing was needed to get everyone between the Canal du Nord and Havrincourt chateau moat.

Third Army gained a foothold in the Hindenburg Line around Havrincourt on 12 September.

Sergeant Laurence Calvert silenced two machine-gun crews as Lieutenant Colonel Peter’s 5th KOYLIs advanced south-west of Havrincourt and eighty men surrendered. He was awarded the Victoria Cross. Captain Crow secured the final objective while the 2/4th York and Lancasters moved up. Lieutenant Colonel Walker’s 5th Duke’s skirted the chateau moat, crossed the Hindenburg front line and then cleared up Havrincourt, while Lieutenant Colonel Wilson’s 2/4th Duke’s took 170 prisoners amongst the tree stumps that had been Havrincourt Wood. The 2/4th Hampshires then later cleared the chateau but Lieutenant Colonel Crouch’s 9th Durhams (Pioneers) could only advance a short distance beyond the Hindenburg front line.

37th Division, 12 to 18 September, Trescault

The 13th KRRC and the 13th Rifle Brigade cleared Trescault on 12 September and then the 10th Royal Fusiliers were engaged in ‘the most protracted bitter and evenly contested actions of this phase’ two days later. Second Lieutenant Frank Young silenced a machine gun so the 1/1st Hertfords could escape from Triangle Wood late on 18 September and he ‘was last seen fighting hand to hand against a considerable number of the enemy’. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

New Zealand Division, 12 September, Gouzeaucourt Wood

Major General Andrew Russell’s men advanced into Havrincourt Wood and Gouzeaucourt Wood. Lance Corporal Turner silenced two machine guns so the 4th Rifle Brigade could advance onto the Trescault Spur, alongside 1st Rifle Brigade. The 2nd Rifle Brigade ‘got close down to the barrage in splendid style’ and entered African Trench. One patrol was cut off after capturing a battery but Sergeant Harry Laurent made sure over one hundred prisoners were escorted back. He was awarded the Victoria Cross.

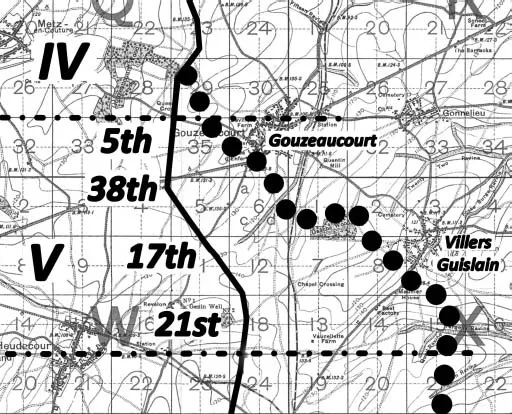

V Corps

5th Division, 18 September, Gouzeaucourt

The 2nd KOSBs’ left reached African Trench in front of Gouzeaucourt but the right was pinned down, so Lieutenant Colonel Furber had to withdraw his men.

38th Division, 18 September, Gouzeaucourt

The 16th Welsh Fusiliers and 14th Welsh Fusiliers reached the outskirts of Gouzeaucourt but the 16th Welsh Fusiliers had to fall back due to enfilade fire until the 13th Welsh Fusiliers covered their left flank. The 13th Welsh came under enfilade fire but Second Lieutenant William White, of the 38th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps, silenced the enemy machine guns. He would be awarded the Victoria Cross. The 14th and 15th Welsh took the rest of the objective in front of Gouzeaucourt.

17th Division, 18 to 20 September, Gouzeaucourt and Gauche Wood

The 10th Lancashire Fusiliers, 12th Manchester and 9th Duke of Wellington’s came under fire as they crossed Chapel Hill at 5.20 am in what was the ‘the stiffest task of the day’. Contact planes warned the 7th East Yorkshires about enemy movements while the 10th West Yorkshires and 6th Dorsets moved closer to Gouzeaucourt. The 7th Lincolns took some 200 prisoners around Gauche Wood while the trench mortars silenced ‘an armoured machine-gun nest’ made out of four derelict British tanks. The 7th Border Regiment and the 10th Sherwoods were then able to enter Gauche Wood. The 6th Dorsets and 10th West Yorkshires took Quentin Redoubt during the night but Lancashire Trench held out. Brigadier Sanders was killed by machine-gun fire while inspecting the captured position on 20 September.

Third Army advanced towards Gouzeaucourt and Villers Guislain to cover Fourth Army’s flank as it pushed through the old British trenches.

21st Division, 18 September, South of Villers Guislain

The ‘appalling weather’ meant that the 1st Lincolns, 12/13th Northumberland Fusiliers and 2nd Lincolns were only just ready in time but ‘they fell upon the enemy with great determination’ around Chapel Hill. The 1st East Yorkshires, 9th KOYLIs and 1st Wiltshires increased the prisoner tally to 700 as they advanced to the next objective but the 6th Leicesters came under enfilade fire because 58th Division could not take Peizières. A counter-attack then drove the Wiltshires back, so the rest of the advance was postponed.

33rd Division, 21 to 24 September, South of Villers Guislain

Lieutenant Colonel Campbell’s 2nd Argylls attacked M...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Regiments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Insufficient to Build an Enduring Defence

- Chapter 2: Ceaseless, Wearing, Unspectacular Fighting

- Chapter 3: On this Day We Buried all our Hopes for Victory

- Chapter 4: The Most Desperately Fought Engagement of the War

- Chapter 5: Fighting with Dash and Determination

- Chapter 6: An Orgy of Fighting and Killing

- Chapter 7: The Reception Accorded the Troops was Historic

- Chapter 8: Reorganise, Push On and Get the Objective

- Chapter 9: More Anxious to be Accepted as Prisoners than to Fight

- Chapter 10: A Most Enthusiastic Reception

- Chapter 11: What is the Good of Going On?

- Chapter 12: A Magnificent Feat of Cool Resolution

- Chapter 13: Practically a Route March

- Chapter 14: Hammering the Hun had Broken Jerry’s Heart

- Chapter 15: Completely Used Up and Burnt to Cinders

- Conclusions

- Plate section