- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Deals with a little-known aspect of the war . . . alongside the moving story of one man's relationship with a very special animal."—

Sqn Ldr Paul Scott

,

Spirit of the Air

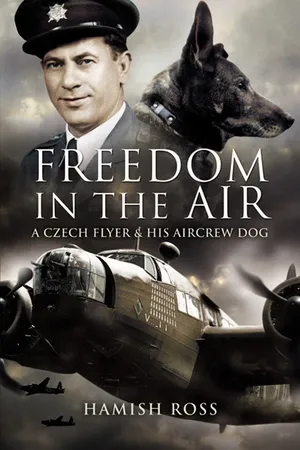

This biography tells of the life of Václav Robert Bozd?ch, a Czech airman who escaped from the Nazi invasion, fought with the French and finally arrived in Britain to fly as an air-gunner with the RAF during World War II. He returned to his homeland after World War II but escaped back to the UK again when the communists gained control. Again he joined the RAF and rose to the rank of Warrant Officer.

The unique part of this is that from his time in France, throughout World War II and until halfway through his second tour with the RAF, Bozd?ch was inseparable from his Alsatian dog, Antis, who became famous and was awarded a dog equivalent to the VC. Antis flew with his owner on many bomber raids, became the squadron mascot and was officially a serving RAF dog. He played an amazing part in the second escape from the Czech communist regime, when Bozd?ch was lucky to make it over the border to the US zone in Germany.

"The main hero of the book is not Bozd?ch himself, but his Alsatian, Antis . . . This book makes clear the extent of wartime and post-war suffering endured by Czechs and others fulfilling their roles in the overall search for freedom."—Aircraft Owner & Pilot

"This absorbing account of flying in WWII is based on the inseparable bond between man and dog. It is a moving story with humor and sadness. A Great Read that is Highly Recommended."— Firetrench

This biography tells of the life of Václav Robert Bozd?ch, a Czech airman who escaped from the Nazi invasion, fought with the French and finally arrived in Britain to fly as an air-gunner with the RAF during World War II. He returned to his homeland after World War II but escaped back to the UK again when the communists gained control. Again he joined the RAF and rose to the rank of Warrant Officer.

The unique part of this is that from his time in France, throughout World War II and until halfway through his second tour with the RAF, Bozd?ch was inseparable from his Alsatian dog, Antis, who became famous and was awarded a dog equivalent to the VC. Antis flew with his owner on many bomber raids, became the squadron mascot and was officially a serving RAF dog. He played an amazing part in the second escape from the Czech communist regime, when Bozd?ch was lucky to make it over the border to the US zone in Germany.

"The main hero of the book is not Bozd?ch himself, but his Alsatian, Antis . . . This book makes clear the extent of wartime and post-war suffering endured by Czechs and others fulfilling their roles in the overall search for freedom."—Aircraft Owner & Pilot

"This absorbing account of flying in WWII is based on the inseparable bond between man and dog. It is a moving story with humor and sadness. A Great Read that is Highly Recommended."— Firetrench

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Freedom in the Air by Hamish Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

CHAPTER ONE

Master Aircrew

As flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods;

They kill us for their sport.

They kill us for their sport.

William Shakespeare, King Lear

Newspapers in Britain, during the Second World War, carried photographs of a Czech airman standing beside his handsome Alsatian dog, called Antis. However, it was the dog that was the subject of the accompanying articles; for equipped with a specially adapted oxygen mask, he accompanied his master on operational sorties over enemy territory with No. 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron of Bomber Command. The newspaper coverage was a distraction from disappointing war news, and it appealed to the public. The phrase ‘dog of war’ often appeared in the headline; the dog’s prowess was written about in magazines and was reported by the BBC; and the war dog tag remained over the decades; it was even repeated when the Alsatian’s Dickin Medal, the so-called ‘Animal VC’, was auctioned by Sotheby’s almost half a century later. But little was written about the airman; indeed in recent time, more was known about him in the Czech Republic than in the UK, although he spent the greater part of his life in Britain, and served for eighteen years in the RAF. In part, it was his own doing: he sought anonymity in the UK because of the postwar political situation in Central Europe, where his family still lived. Yet Darryl F. Zanuck, the head of Production at Twentieth Century Fox, wanted to make a film about the airman and Antis, and sent representatives to meet him at RAF Lyneham,1 then went himself to meet him to discuss the project. It was not until after the fall of communism that the story of Václav Robert Bozděch could be researched and told.

That story certainly encompasses the extraordinarily strong bonding between the airman and his dog. With the passage of time, this episode in Bozděch’s life seems all the more incredible, yet it is true: a dog of great loyalty, courage and intelligence, lying alongside his master’s feet in the gun turret of a Wellington bomber, on operation after operation during the bombing campaign of 1941, sensing and sharing the men’s fear of the flak and the night fighters; he was wounded twice by enemy fire, and ultimately, in recognition of his bravery, he had the ribbon of the Dickin Medal (the ‘Animal VC’) attached to his collar by Field Marshall Wavell. Of course, the dog’s operational sorties were completely at variance with RAF regulations. But then the circumstances were unique. It all happened at a time when Britain’s position was still precarious; the United States had not yet entered the war; and Bomber Command was the only force capable of hitting the enemy heartland. It was a time too when aircrews had strong superstitions about what brought good luck in a campaign where losses were high; and then there was the verve and panache of the Czech crew, highly motivated men, their country already under the jackboot, accepting the Alsatian as one of the combat team.

However, the story has deeper levels. It spans the final years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the fall of communism, and arises out of the history and politics of Central Europe in the 1930s and 1940s; it is set in the context of the airmen and their belief in what they were fighting for, and the grave injustice that they subsequently suffered at the hands of a Stalinist regime for having served their country in the west; and it does not reach resolution until the end of the twentieth century. Bozděch’s story tells of one man’s response to the powerful external forces that can break the individual; it tells of resisting, and of the acceptance of loss; it is redolent of loyalty and endurance, for which his canine comrade-in-arms is a powerful symbol.

Like other Czechoslovak career servicemen who fled their country in 1939 in the hope of taking up arms to free it, after it fell under Nazi rule, Bozděch had first to sign the five-year contract of the French Foreign Legion and was transported to the Middle East. Then when war was declared, he transferred to the French Air Force and served with it during 1939/40; and it was during this period that he acquired the dog that would be his companion for thirteen years. After the fall of France, he made his way to England, breached Britain’s strict quarantine laws by smuggling the dog ashore, and rejoined the Czechoslovak Air Force, which was incorporated into the RAF. He served for five years in Fighter, Bomber, Training and Coastal Commands, and was decorated with the Czechoslovak Medal of Valour and the War Cross.

Political manoeuvring among the Allies over the liberation of the occupied territories as the war moved into its final stages foreshadowed the uneasy restoration of democracy in the homeland: the West’s disinclination to trespass into the Soviet sphere of influence, as the Red Army and General Patton’s army both converged on the country’s borders during the Prague Uprising, turned out to be a strategic error.

At the end of the war, after numerous delays, the Czechoslovak Squadrons made a triumphant return to Prague, but found that their defence of democracy had also come at a high price for their families during the Occupation, if the Gestapo discovered that relatives were serving with the Allies. Some learned that their family had perished in the death camps. In Bozděch’s case, his mother had been sent to an internment camp in Moravia.2 She had survived but her health was seriously impaired.

He became a staff captain in the Air Force, working in the Defence Ministry; and he was friendly with the country’s Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, who was godfather to his son. He wrote several books and a radio script about the air force in the Second World War; and to his writing he brought a depth of experience, but he also had support from well-placed sources. He was given permission for one book to quote from the transcripts of speeches by President Beneš,3 and in another he was allowed to reproduce letters from the wife of the President.4 Two weeks after the communist coup in 1948, the body of Jan Masaryk was found amid suspicious circumstances in the courtyard of the Ministry. Bozděch later wrote that the two had met three days before Masaryk’s death, and Masaryk had told him that he knew the airman was on a purge list.5 No public inquiry into Masaryk’s death took place; it was put out that it was suicide. Bozděch conferred with his commanding officer6 and others he trusted; various pairing options for escape were considered, before he made his attempt. It was a bold attempt, carried out from the Defence Ministry on a working day; he had to leave his wife and infant son, but he took Antis with him on the perilous border crossing.

Two months followed in refugee camps in West Germany before he was able to rejoin the RAF; and he went from staff captain to aircraftsman in one move, for while the British Air Ministry waived nationality regulations to allow former members of the Czechoslovak squadrons back into the service, its policy was to put them at the lowest rank to begin with. Bozděch’s next step was back into aircrew at an Advanced Air Training School. Antis became a celebrity with the award of the Dickin Medal. The ceremony appeared on newsreels and in the press, but Bozděch kept well out of the limelight. Officialdom now looked indulgently on that irregular crewing of a Wellington bomber in No. 311 Squadron all those years before: Antis became squadron mascot, and Bozděch was not posted overseas during the remaining years he had the dog. They made their last flight together, on a troop dropping exercise; it was a nostalgic short trip in a Dakota over East Wretham, the airfield from which No. 311 Squadron had flown when it was in Bomber Command. Aged almost fourteen years, all but three of which were spent on air force stations, Antis died, and was buried in the Animal Cemetery at Ilford.

Bozděch had already been arraigned in his absence by the High Military Prosecutor in Prague for treason, conspiring against the state and desertion.7 The regime would not allow the families of émigrés to be reunited; and the partner remaining in the homeland was pressured to petition for divorce. Now flying with Transport Command, Bozděch found ways of circumventing the regime’s practice of intercepting incoming mail from marked émigrés like himself by writing under assumed names from third world countries.

While he was stationed at RAF Lyneham, in between flying on Transport Command’s world routes, and serving in the Suez campaign, he devoted his free time and his energies to writing the manuscript of a book on his life with his dog. The outcome was impressive: the film rights of his story were bought by Twentieth Century Fox, and he had a meeting with Darryl F. Zanuck who was going to produce a film version. In 1962, Bozděch left the RAF. Civilian life was spent quietly with his second family in Devon; he became a successful small entrepreneur; and he carried out research into his old wartime squadron. He was never allowed a visa to return to his homeland, even although he appealed to the Czechoslovak Ambassador in London.8 He died of cancer in 1980.

However, the story does not end with his death. Resolution of its elements could only come about after the fall of communism; and with the restoration of democracy, came restitution for those who had suffered at the hands of the regime, or had fled to avoid being persecuted. Posthumously Bozděch was advanced to the rank of colonel in the Czechoslovak Air Force; two of his books, banned for decades, were republished. Following a forensic expert’s investigation into the death of Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk in the courtyard of the Ministry all those years earlier, the Czech police opened the case, then formally concluded that Masaryk had indeed been murdered. Bozděch’s families in the UK and the Czech Republic finally met. And as a result, his story can now be told.

A range of sources exists, both in the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom. The Military Archive in Prague is particularly useful because it tracks an airman’s career during the pre-war years, wartime (for the Czechoslovak Squadrons remained in their own country’s air force at the same time as they were part of the RAF) and the postwar period. Because he was the subject of security investigation, the Archive of the Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic contains very detailed records on Bozděch. In the United Kingdom there are the RAF operational record books for No. 311 (Czechoslovak) Squadron, which are contained in the National Archives; and information has also been obtained from the Air Historical Branch of the RAF, the Royal Air Force Personnel Management Agency and the Free Czechoslovak Air Force Association. In addition, the research is supported with transcripts of interviews with a number of Bozděch’s contemporaries, as well as his family in the UK, and in the Czech Republic.

Maureen Bozděch has given access to her late husband’s manuscript, papers and tapes; and these offer the deepest insights into the man. His papers show that he was penetrating in discernment and tenacious in arguing about principle. He was both a maverick and yet he was service-minded. The rank that he held for some time in the mid 1950s was appositely titled Master Aircrew: he was a very capable individual. In some respects he was typically Czech: undemonstrative, self-effacing, but he would survive and he could adapt to whatever situation he found himself in – whether it was as a staff officer in the corridors of power in the Defence Ministry in Prague, or in the NCOs’ mess of a Royal Air Force station. But he was a troubled man too, ruminating silently over the suffering he had brought to his family, both during the war and under the communist regime.

Translations from the Czech of extracts from his book Gentlemen of the Dusk add a dimension to the war years. His English language manuscript, which he titled Antis VC, adds texture to the research: it supplements the operational record books of No. 311 Squadron; it deals with areas not covered by official documentation; and while Bozděch concealed more than he revealed in the section on his escape from Prague, he developed the frontier crossing by night in April into a taut and well structured account. Above all, both the manuscript and the tapes reveal the strength of his attachment to Antis.

He would not have seen himself in a heroic mould; but then he was a representative of a cohort of his compatriots, few of whom would have considered themselves in that mould. For they were not adventurers; they fought for freedom, and later suffered for it, through persecution or exile. So Bozděch’s story is not bound by time or place; its elements: defending ideals, the primacy of survival, the enforced separation of families, the role of Antis in his life – a variation on that ancient association between man and dog – give rise to themes that are timeless.

CHAPTER TWO

Young Democracy

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

But to be young was very heaven!

William Wordsworth, The Prelude (1850)

At the time Václav Bozděch was born in western Bohemia in 1912, his parents were subjects of Emperor Franz Joseph, dynastic head of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; but by the time he was in his first year of primary school, they were citizens of the democratic Republic of Czechoslovakia, under the leadership of its liberator-president Tomaš Masaryk.

The Czech lands of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia had been part of the amorphous Austro-Hungarian Empire for centuries, and German took ascendancy over the Czech language. But the nineteenth century saw a remarkable resurgence of Czech culture, to such an extent indeed, that by the first decade of the twentieth century the Czech lands amounted to a nation without a state.1 From those lands there emerged a number of potential political leaders – not from an existing ruling class, but intellectuals born of peasant stock – like Professor Tomaš Masaryk, who, in 1900 had helped found the Czech People’s Party, and Dr Edvard Beneš, who both played key roles in bringing the state into being. The Great War was the catalyst that brought about the political and military activity on the part of Czechs and Slovaks, which secured their statehood.

When that war came Masaryk left Prague and based himself in London, and Beneš went to Paris; for if statehood were to be re-established to their people, it would have to be as a result of the overthrow of the empire of which they...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Part I

- PART II

- PART III

- PART IV

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index