eBook - ePub

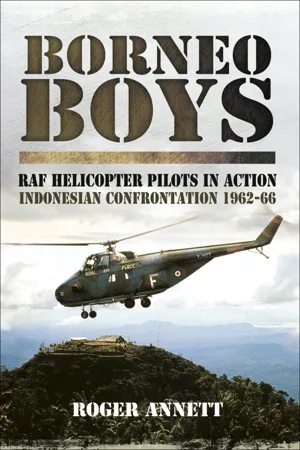

Borneo Boys: RAF Helicopter Pilots in Action

Indonesia Confrontation, 1962–66

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author, Roger Annett, experienced first-hand the events detailed here. Flying with 215 Squadron, and co-piloting Argosy transport aircraft deep over Malayan jungle terrain from 1963 to 65, he is well placed to provide a colorful account of this dramatic period. Following a reunion of RAF Whirlwind veterans of Borneo, Annett began work on this record of their collective experience, attempting to stir the memories of both war veterans and civilians alike, riveted by the drama as it played out by opposing forces attempting to control the island of Borneo.The book describes the oppositions, antagonisms, victories, and defeats experienced on the island. Borneo itself, with its difficult terrain, jungles, and lack of adequate road networks, proved to be one of the biggest challenges from a military perspective, and it is brought to life here. The story of the 'Borneo Boys' of the title traces a journey from new recruits at boot camp to flying training, and on to Borneo itself. It was here where a fraternal bond was to be forged to last a lifetime and provide an impetus for this book. The process of Theatre familiarization jungle training, nursing Whirlwind 10s over and around the mountainous Malayan jungle is recorded here with first-hand authenticity.Setting this journey in context, Annett fills out the history of the wider conflict in which the boys were embroiled. The Far East colonial tensions, which bred antagonism and ultimately led to the conflict, are detailed, as are the cross-border raids and riots, which bred a fever of revolt.Much is written already on the Borneo conflict, a lot of it dealing with the politics of the situation. This book swoops its focus on the young men who were called upon to fly over such confusion, far away from home. It is their daily adventures, camaraderie, and learning trajectory, which we are faced with. All the excitement of the Aviator's adrenalin ride is translated into eloquent prose, strengthened by the kind of confident delivery that only a man involved in such proceedings could achieve.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Borneo Boys: RAF Helicopter Pilots in Action by Roger Annett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Brunei Rebellion

Tensions in the oil-rich sultanate of Brunei had been building since the Second World War when, early in 1942, the Japanese Imperial Army invaded South East Asia. As they pushed west, they occupied the whole of Borneo, establishing bases at Tarakan on the east coast and Labuan on the north-west. They imposed a brutal regime on both the British and Dutch colonies and it was not until 1944, as the tide of war in the Pacific was on the turn for the invaders, that the Allies could strike back.

One Englishman, the anthropologist and Specialist Operations Executive (SOE) recruit Tom Harrisson, together with three Australian soldiers parachuted into the northern highlands of Borneo to recruit tens of thousands of willing native head-hunters into a guerrilla force. These semut (ants) harassed the Japanese with British-supplied shotguns, their indigenous razor-sharp parangs and poisonous blow-pipe darts softening them up for the liberating Australian battalions that arrived in 1945. Pursued up the rivers to the mountains, the hapless occupiers suffered heavy losses before the atomic bombing of their homeland gave them the relief of surrender in August 1945.

In British Borneo, 200 years of imperial rule had been relatively liberal, the colonial administrators respecting the free-trading traditions and animist beliefs of the multitude of tribal groups and when British administrators returned to Sarawak, Brunei and British North Borneo affairs reverted much to the earlier status quo. However, the southern three-quarters of the island, Kalimantan, along with most of Indonesia, had been the preserve of Dutch colonials, hated for their cruelty and oppression. A populist political leader, Dr Achmed Sukarno, used the post-war power vacuum and surrendered Japanese weapons to seize control in Djakarta. It took four divisions of British and Indian troops, supported by around one hundred RAF aircraft, to restore order, enabling the Dutch to return to the Netherlands East Indies at the end of 1946.

To the Indonesians, the British were now bracketed with the Dutch as colonial oppressors and when, in 1949, backed by the United Nations, the nationalists threw out the Dutch and gained their independence, Sukarno, now head of state, became intent on disposing of British rule over northern Borneo. His resolve was strengthened when Communist insurgents appeared to gain the upper hand over the British in the 1950s Malayan Emergency.

Sukarno had in mind a Confederation of Malay states in South East Asia which he dubbed ‘Maphilindo’ – a combination of Malaya, the Philippines and Indonesia. He lobbied the United Nations and the United States for support and found some sympathy – the Americans in particular saw the potential that such a power-bloc might have for stability in the Pacific Rim. In response, the Malayan government under Tunku Abdul Rahman, encouraged by the British, developed a counter-proposal – for a Federation of Malaya, Singapore and the British Borneo states, ‘Malaysia’. Sukarno saw this as a direct challenge from colonialists and was determined to thwart the Tunku’s plans. He saw an opportunity for direct action in Brunei.

A Sultanate of two enclaves amounting in total to just 2,226 square-miles, Brunei sat between the British colonies of Sarawak and North Borneo, facing Labuan Island across the bay to the north. It was rich in agriculture and timber, and extracted four million tons of crude oil annually. Much of this was refined under concession in the coastal town of Seria by Shell Petroleum, a British company. The oil brought immense wealth to the Sultan and his entourage, but nonetheless, the majority of the 85,000 population, the Malays, revered him. Most of the Chinese, who made up one quarter of the inhabitants but were denied citizenship, may have harboured some resentment, but generally prospered in trade and commerce. The various indigenous tribes, isolated in longhouse and kelong, were remote from politics.

Riverside longhouse. (Colin Ford)

But Sukarno, seeking not only to destabilize project Malaysia but also to seize the oil and its revenue, succeeded in gaining the support of the militant wing of the popular People’s Party, the so-called North Kalimantan National Army (TNKU). Fronted by a local firebrand politician, A. M. Azahari, this force cobbled together fifteen companies of semi-trained ‘volunteers’ armed with a few Indonesian machine guns as well as a couple of hundred shotguns remaining from the wartime semut action. They were backed by 8,000 untrained but enthusiastic parang-wielding supporters. At two in the morning of 8 December 1962, the rebels rose up, attacking and occupying the police station in Brunei town.

Their objectives were to capture the Sultan and install him as a figurehead before looting supplies and further weapons from police stations. They planned then to capture oilfields and European hostages to use as bargaining counters with the British. Their long-term aim was an independent People’s Republic of Borneo. As a plan it was sound, but their line of command was weak (at the time of the uprising, Azahari was safely ensconced in Manila) and, crucially, the mass of the armed supporters were not made aware of the time and date of kick-off. In addition, the TNKU had failed to target Brunei airfield, situated in a key position just north of the town, on the river and no more than ten miles from the sea.

Although the timing of the uprising had taken them by surprise, British and Malay commanders and local administrators had for some time been preparing for trouble. Sukarno’s threats against the proposed Malaysian Federation had prompted a build-up of forces in the British sovereign bases of Singapore, which comprised three RAF airfields, the Naval Base of the Far East Fleet, the FAA air-base and a half-dozen barracks of regular British and Gurkha troops.

As news of the rebellion reached the British High Command in Singapore, events moved fast – even though it was a largely off-duty Saturday – and within hours two companies of King Edward’s Own Gurkhas and 1st Royal Green Jackets boarded Beverley transports of 34 Squadron RAF for the four-hour flight to Labuan. Overnight, they were inserted unopposed at Brunei Town airfield and fought their way through the streets before setting off on the sixty-mile road to Seria. There, the rebels had reportedly captured Anduki airfield and the refinery and taken their European hostages – the police station, however, was holding out.

It was monsoon season and a disrupting seventeen inches of rain had fallen in four days, but, nevertheless, the convoy made good progress but were held up by a rebel strongpoint at Tutong. It became clear that to relieve the serious situation at the refinery a flanking attack was needed. It came on Monday 10th in the form of a Beverley transport of 34 Squadron RAF, which braved the weather and rebel machine-gun fire to insert ninety men of the recently-arrived Queen’s Own Highlanders at Anduki airstrip. The captain, in an outstanding display of airmanship, managed to land, discharge the warrior Scotsmen, and roar back into the air within the length of the saturated, jungle-fringed strip – all inside a remarkable ninety seconds. At the same time, five Twin Pioneers of 209 Squadron landed two dozen more Highlanders on rough ground behind the police station. Seria was cleared of rebels, and all hostages were released unharmed, within two days.

Meanwhile, on the day of the uprising, HMS Albion was on the Indian Ocean, five days out of Mombasa en-route the Far East, carrying the men of 40 Commando Royal Marines and their equipment. Also on board were the Wessex Mk 1 helicopters of 845 Naval Air Squadron (NAS) and Whirlwind Mk 7s of 846, flown by ‘Junglies’, a term coined by Lord Louis Mountbatten for the courageous pilots who operated early marks of Whirlwind in Malaya.

The ship received a signal from the C-in-C Far East Station: ‘Proceed with full dispatch Singapore’. The engineers wound up her turbines to record speeds and she ploughed her way to the Singapore Naval Base in four days, arriving on 13 December and staying just long enough to embark a further Commando, 42. Within five days of receiving the first signal, she anchored off Kuching and disembarked 40 Commando, who took up positions along the Indonesian border. The following day, 846 NAS Whirlwinds flew into Seria, and the Wessex of 845 into Brunei, where they and 42 Commando were straight into the action. Theirs was to be the first of many helicopter-aided operations in the Borneo Campaign.

Eighty-nine Marines famously made a river assault at Limbang from two un-armoured and unarmed lighters pressed into service as landing craft. In a brisk fire-fight, the town was cleared of upwards of 350 rebels and the Resident, his wife and six other hostages were rescued in the nick of time. The TNKU force was routed with fifteen dead and eight captured (42 Commando losing five and suffering eight wounded) and the back of the rebellion was broken. Tom Harrisson, now resident in Sarawak, had roused his old friends the irregulars and, armed with shotguns and spears, they now moved in to cut off the rebels’ escape routes.

The naval helicopters were tasked with troop lifts and casevac, together with interceptions of suspicious water-borne craft, and flew close on 2,000 sorties in the first twenty-six days. It was a sign of devolved authority to come that Albion’s commander, Captain Madden, directed the army bosses on the spot to use the helicopters as required, without the necessity of referring back to him. The Junglies were to remain in the challenging monsoon conditions of Brunei for six weeks, before flying off to the Albion for rest and repair.

Within days, there was a score of helicopters in action, as four brand-new RAF twin-rotor Bristol Belvederes of 66 Squadron, and the same number of ageing Sycamores of 110, as well as Westland Scouts of 656 Squadron, Army Air Corps (AAC) found their way up to Brunei to join the fray. Some were ferried by Albion, others were loaded into Beverleys in Singapore and flown north but three of the Belvederes, fitted with internal overload fuel-tanks, managed a dawn running-lift-off from RAF Seletar to pioneer a historic flight of 400 nautical miles over the South China Sea to Kuching. They did that in four hours and, after refuelling and refreshment, rattled their way another 400 miles up to Labuan before nightfall.

Working closely with army commanders, helicopter support greatly assisted in bringing the main action in Brunei to an end by the turn of the year. There was no further organized aggression from the TNKU, but it took until the middle of May 1963 to round up the entire rebel force, estimated at 5,000 strong.

Crest of 66 Squadron RAF: motto translates as ‘Beware, I have warned’. (Crown Copyright)

There had been little sign of Indonesian direct involvement during the Brunei Rebellion. British Intelligence Staff reckoned that Sukarno had threatened to send in volunteers but the uprising had collapsed before he could act. Nevertheless, the torrent of vitriolic propaganda from Djakarta continued and, in April 1963, Sukarno made public his policy of Konfrontasi against the proposed Malaysia. He gave notice of his intentions when a party of thirty Indonesian Border Terrorists (IBTs) crossed the frontier south of Kuching, attacking the police station at Tebedu. The small defending force of Malay Border Scouts was taken by surprise, the raiders killing a corporal and wounding two policemen before looting the bazaar and making their way back over the border.

Daggers had been drawn. The build-up of forces gained pace on both sides.

Chapter 2

Tern Hill Tyros

Despite being caught on the hop by the Brunei rebellion, British forces and their indigenous allies managed to prevail in the action without heavy casualties, and took heed of the lessons learnt. The first was the need for a joint command structure, the better to co-ordinate the various Army, Navy and Air Force assets available. As a result, by 19 December 1962, a Joint HQ had been established at a girls’ school in Brunei town, reporting directly to the C-in-C Far East. Appointed as first overall Director of Operations was Major General Walter Walker, who had learnt his jungle warfare principles as a Gurkha Brigade Commander in Malaya.

The second lesson was that a surveillance and reconnaissance capability was urgently needed – timely and accurate intelligence was essential in denying the enemy the advantage of surprise. Thirdly, winning the ‘hearts and minds’ of the Borneo tribal groups over to the defenders’ cause would assist in gathering that intelligence and ensure that tribesmen were supportive of, not hostile to, British troops on jungle patrols. Fourthly, Walker knew from his time in Malaya that to dominate the jungle, his forces must operate from secure bases – plans were laid to establish a series of forts along the border.

And finally, it was obvious that the rotaries of the Army, Navy and Air Force could, with their inherent speed and flexibility, ensure the maximum of mobility in this battlefield of mountain, jungle and swamp. Walker needed more helicopters.

As part of that rotary reinforcement, orders were placed by the then Air Ministry for Whirlwind HAR Mk 10s, a development of the machines which since the early 1950s had been manufactured by Westland Aircraft in Somerset for the Royal Navy, under licence from the American Sikorsky Corporation. RAF Flying Training Command was tasked with sourcing the pilots to fly the new machines.

Up to then, ‘choppers’ had been considered by career-minded officers as being well off the beaten track and, as a result, they were crewed by NCO pilots and older air-crew officers nearing the end of their service. A fresher, as well as larger intake was needed. Pilots who had completed their first tour on fixed-wing aircraft were targeted, as were others entirely new to the service, detailed for helicopters after fixed-wing ab initio training. These were the Borneo Boys.

Colin Ford was among the first of the new joiners. Colin was born in December 1941 in Rawalpindi, where his father served with the British Army in India. The Ford family returned to England in 1945, and in due course Colin gained a place at Westcliff High School for Boys, in Essex. But army postings moved his father and family to Germany and he was sent to board at Prince Rupert School in Wilhemshaven – an experience, he says, which helped prepare him for later institutionalized life. At the end of the posting, Colin returned to Westcliff for ‘A’ Levels. With one brother in the Army and another in the Navy, and having a yearning since an early age to fly the Vampire jet, the RAF was his obvious choice. He was offered a commission on the Supplementary (Flying) List, and looked forward to his coveted pilot training. But the first stage was Initial Officer Training (IOT) and in November 1960, aged eighteen, he reported for boot camp at RAF South Cerney, north-west of Swindon.

On the same course as Colin was Ian Morgan, also eighteen years old. Born in Middlesbrough, North Yorks, where his father was a Teesside steel works engineer, Ian was sent away to boarding school in the remote Barnard Castle, where he joined the CCF. But that was all-army, and Ian had no thought of the RAF until a chum persuaded him in 1960 to join him on a trip down to Hornchurch, where he was to take the pilot-aptitude tests. Ian thought that sounded like fun, particularly the flying and the prospect of travel, and applied. He was offered a place at the RAF College, Cranwell, provided he gained two A-levels. Passing just the one, Biology, he also took the Direct Entry Commission route, signing on for a sixteen-year stint.

On graduation from IOT, Acting Pilot Officers (APOs) Morgan and Ford went on to No. 2 Flying Training School (FTS) at RAF Syerston in Nottinghamshire, and the newly-introduced Percival Jet Provost Mk 3 trainer. The flying was often disrupted by the fog which regularly crept in over the River Trent, and there was a a drop-out rate of around 33 per cent, but both lads took naturally to the...

Table of contents

- Also by

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Glossary

- Prelude

- Chapter 1 - The Brunei Rebellion

- Chapter 2 - Tern Hill Tyros

- Chapter 3 - The Sharp End

- Chapter 4 - Into the Fray

- Chapter 5 - The Pace Quickens

- Chapter 6 - Frontier in Flames

- Chapter 7 - RAF Navigator on Naval Base

- Chapter 8 - At Full Throttle

- Chapter 9 - Transfer to 225

- Chapter 10 - Over the Border

- Chapter 11 - Conversions to Rotaries

- Chapter 12 - Holding the Line

- Chapter 13 - Showdown at Plaman Mapu

- Chapter 14 - Counter-Punch

- Chapter 15 - Views from the Ground

- Chapter 16 - The Sparring Continues

- Chapter 17 - Stalemate

- Chapter 18 - The High Tide Turns

- Chapter 19 - Jungly Mission to the Gaat

- Chapter 20 - Shadow-boxing

- Chapter 21 - The Bumpy Road to Peace

- Chapter 22 - Mopping Up

- Postlude

- Appendix 1 - Post-Borneo Curricula Vitae

- Appendix 2 - A Week in the Life of Colin Ford

- Appendix 3 - Self Athorisation Certificates

- Appendix 4 - Mike McKinley’s Flying Logbook Extracts

- Appendix 5 - Presentations made to 225 Squadron RAF during their two years in Borneo

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index